Chandramolle Modgil: How significant is wood, as a raw material, in Himalayan Buddhist structures?

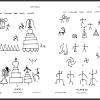

Laxman S. Thakur: Whether in Buddhist or brahmanical structures, wood has been very used prominently. In Himachal, there is archaeological evidence of wood right from the first century CE, when some kind of structures from this region appear on the coins of the Audambaras and Trigarthas. Specifically, the structures on the Audumbara coins look very much like the temples, what I call the ‘pent-roofed’ style of temples. One of the structures on the Trigarta coins, looks like the ‘pagoda’ style temple. Pagoda-style temples are those which have a set of umbrellas one upon the other. For the sake of convenience, it is called the ‘pagoda’ style of temples. Wood features frequently on most of the structures, religious or secular―be it brahmanical temples or Buddhist monasteries.

C.M.: Let us presently focus on Buddhist structures. Can you classify some of these structures based on woodwork in this region?

L.S.T.: Buddhist monasteries in Himachal Pradesh can be classified into four categories. This classification is based on Vastu-Shastric injunctions. In my attempt to classify the temples of Himachal Pradesh in my work, The Architectural Heritage of Himachal Pradesh: Origin and Development of Temple Styles, I found it is not always possible to categorize structures on the basis of raw material. A classification based on terms like ‘wooden temples’ or ‘stone temples’ is faulty.

The first type is the Nagara style. For example, the Trilokanath Temple in Lahaul Spiti is of the Nagara style. This style was very popular in Chamba and other areas. And, then it migrated to Chamba-Lahaul. But it does not change the function of the temple as a Buddhist temple because Avalokiteshvara statues were found there in the garbhagriha of the temple. The second category is the flat-roofed style monasteries, dominating the Lahual-Spiti-Kinnaur region of Himachal. Here wood has been used for doors as well as the structures. Third, there are pent-roofed style Buddhist structures in Kinnaur, which can be single, double, or multi-storied. My friend Penelope Chetwode used to call it the ‘chalet’ style, because they resemble the small Swiss shrines, though I have my doubts about this foreign nomenclature. I told her that why do we need to import this term ‘chalet’ because people are not aware of this. Also, because Vastu Shastra classifies temples based on either plan or roof, which are the only two bases for classifications that people are not aware of. I have also tried to clarify this in my work. I believe this is the correct way of classifying a monument. Hermann Goetz has written a book, Wooden Temples of Himachal Pradesh, Wooden Temples of Chamba, etc. Even Handa’s book has come out with the title, Temple Architecture of Western Himalaya: Wooden Temples. Material is not a correct base for classification because wood and stone are used alongside in temple architecture.

This is highly erroneous. Even a single temple style, like the Nagara, or the north Indian temple has many sub-categories. The Vishnudharmottampurana has classified the Nagara style into 110 types: Mahamaru, Mahagujar, Vallabhi, etc. For example, the Sun temple in Orissa is a Nagara style temple, but it is called Rekhadeula in common parlance in accordance with the Shilpaprakash text from Orissa. Without familiarity with Vastu Shastra, it is impossible to study such structures. These are not simply structures but have more content in terms of the injunctions of the Vastu Shastra.

In Kinnaur, there were two-three pagoda-style monasteries: one of them has now burnt down, the one at Ribba―called the ‘temple of the goddess’, Lakhang Chenpo. We derived the name from the inscription on the monument there but unfortunately, everything was lost in the fire. (Now, I think it is being reconstructed at the same place. Maybe it has been completed.) Before that, we were able to document, preserve and publish it, beautifully illustrated. This was one of the most spectacular examples of wood architecture and carving in the region of Kinnaur, Lahaul and Spiti, which we dated to the second half of the 10th century CE.

Among the flat-roofed types, we still have some surviving wooden doors and jambs. Two doors are in the Tabo monastery complex, Jambay Lhakhang i.e., Temple of the Maitreya, one in the larger temple and one in the smaller. Both the temples have original deodar wooden doors. Ropa monastery also has wooden carved doors; also, Sungwa monastery in Charand in Kinnaur has also preserved the original wooden structure. There are some monuments within the Napo monastery complex with surviving wooden doors and parts.

C.M.: What can you tell us about the vernacular wooden monuments?

L.S.T.: Vernacular architecture can be divided into two or three types as well. The existing forts, in Lahaul, Spiti and Kinnaur, of royalty display wooden carving. Secular monuments like houses of people contain wooden carving as well, owing to the fascination of Himalayan folk with this type of ornamentation―doors, jambs and lintels are carved. They have even carved wooden boxes in their houses. The woodworking artisan families still exist in parts of the state, especially in Kinnaur. I have seen a workshop in Chitkul, a village in Kinnaur district, where they were carving some doors and jambs for a dilapidated temple or secular building.

C.M.: Are there particular names given to different vernacular structures? For example the Kath-Khuni, style?

L.S.T.: Kath-Khuni is a technique, not a style, meaning you have an angle in the wood (kath me kuhni) it resembles an elbow-like ('kohni') placement in wood. The structures based on this technique is not entirely a wooden structure but have alternating courses of wood and stone. For example, the Chaini–kothi in Kullu and a lot of pent-roofed style temples. These structures are in Kath-Khuni technique but the style is different. This Kath-Khuni technique of building is an earthquake-proof technique―never collapses. Wood is easily available in the entire Himalayan terrain so this technique is not really peculiar to any particular region.

C.M.: Please elaborate on the development of religious Buddhist structures in Himachal Pradesh. Also, were there any overlaps between the Buddhist and Brahmanical monuments?

L.S.T.: The earliest example of Buddhist architecture in Himachal seems to the Ribba monastery, followed by Charand and Tabo. What is very interesting to note is that the width and length of the wooden doors in Tabo follow the same proportions prescribed in the Brahmanical texts. The Agni Purana and Matsya Purana prescribes that the height of the temple should be double to its width. So, these two temples in the Tabo monastic complex follow very strictly the ratio of one to two proportion. Which means the architects who built these temples were familiar with the Vastu-Shastric injunctions. Similarly, all Nagara temples from 7th-15th century, follow same injunctions for the widths and lengths of the doors. The other interesting aspect is that the carving on the number of jambs and lintels are always in odd numbers. Vastu Shastra lays down there should be three, five or seven depictions, which was followed strictly on both kinds of religious structures. Third, many structures discovered in the monasteries, like Ropa and Charand, they follow the tala-mana system, the iconographic system describing the balance of the various elements of a body. The idols and figures follow this system strictly, whether in stone, clay or wood. This started in the Buddhist monasteries a little later in the structures of the Gelukpa sect of Buddhism. There were several sects within Buddhism. In addition, a feature to distinction in some of the monasteries is the fluted pillars. This technique came to India from the Greeks, the Gandhara art. In Tabo and Ribba there was a symbol of Greek origin, the trefoiled arch, also used in the façade of the Lakshana Devi temple. I have discussed how this feature travelled from Gandhara region to Kashmir, to Chamba, Kullu and Lahaul Spiti to Tibet. Art travelled, there were not many restrictions or boundaries. In one of the recent papers I presented, on the style of sculptures and paintings and wood-carving traditions of this region, I have questioned the nomenclature invented by early scholars. I prefer to call it the Gari style. Gari is a geographical and cultural region, not a political region. Previously, the styles have been named after conquests, but politics does not affect art. The style continues. This Gari style can be applied to wood-carving traditions on doors, jambs and lintels from middle of the 10th to 15th century. There are of course many changes through the period in the style from the west to east borders of the region.

When these monastic structures were constructed in the past in this area, one of the prominent Lotsawa (Tibetan translators of Sanskrit Buddhist texts) called Rinchen Zangpo who was sent by the king of western Tibet to study Sanskrit in India, spent 17 years in India and then started with the building work. He spent some years in Kashmir and some in Magadha. He started construction of the monasteries in the some regions in Tibet. He took 32 artists from Kashmir along. Taking with them the technique of construction of the monasteries, the Vastu Shastric tenets, the tala-mana system in the first phase, and new people who were trained by them and this art style continued in practice until the middle of the 15th century when new art waves from Nepal, the Newari style, and from central Tibet the art of painting clouds came in. Then it has new symbols from China and Central Asia, the style gradually changes through the centuries from what it was earlier. This style has several sub-styles as well. E.g. the crown on the heads of Buddist Gods and Goddesses, earrings, a carving of some sort of horn above the ear, narrow waists of gods and goddesses which is called damrumadhya in Vastu Shastra. So I have identified these characteristics of what I call the Gari style.

C.M.: Please throw some light on the wooden mask-making tradition of Himachal.

L.S.T.: Many monasteries hold a collection of wooden masks, most of which are worn by Buddhist monks during festivals, like Losar―the New Year festival; or at the time of the passing away of a monk; any such occasions organized in the monastic complexes. The main idea of presenting a ‘devil’ dance or a mask-dance is to ward off evil spirits. Monastic folk who believe in ancestor gods and goddesses prior to the influence of Buddhist religion also believe in evil that destroys their progeny, crops and property, which gives way to this periodic feature of wearing masks. There is a good collection of masks in the Tabo monastery, also in the Napo, Charag and Ropa monastery, very rarely used, although recently worn by lamas at their dance performances.