A legacy of distinctive traditional building practice known as kath-khuni construction, survives and thrives in the Himalayan hills of India. A natural extension to the knowledge of forbidding landscape, harsh climate, availability of local materials and tools, the resultant building practice is deeply rooted to the environment and the cultural practices and traditions of the region. Having evolved over a large span of time, passed on by generation after generation, it demonstrates profound understanding of building science that responds to the frequent seismic tremors that rock the landscape of Himachal. This article highlights the various construction elements, materials and joinery details in traditional kath-khuni construction and the resulting compositional richness in the making of walls, openings and corners that reflect the integrity and beauty of Himalayan architecture.

Fig. 1: Panorama showing an old tower temple sitting at the highest point and typical settlement draped around the contoured sunny slopes of the hills in Chitkul, Kinnaur.

The state of Himachal Pradesh varies in elevation from 450 meters to 6500 meters above mean sea level. The region extends from the Shivalik range to the Great Himalayas. Despite its varying topography, the stretch displays a relative consistency and homogeneity of traditional construction and material with slight variations. In the mid and central Himalayas, a particular architecture has extensively developed locally known as kath-khuni construction.

Kath-khuni is a type of cator-and-cribbage building which employs locally available wood and stone as prime materials for construction. The origin of the term is explained by O.C. Handa (2008) as ‘…combination of two local terms: kath and kuni. The word kath is a dialectal variation of the Sanskrit word kashtth, which means wood, and kuni is again a dialectical variation of the Sanskrit word kona, that is, an angle or a corner. Obviously, the kath-khuni wall implies it should have only wood on its corner or angles.’ There are several variations observed from region to region. It is also known as kath-kona, kath-ki-kanni, koti banal in Uttarakhand etc.

The widespread technique of kath-khuni construction can be found in buildings of various scales, from quite large darbargadhs and kots, to intricate and majestic temples, to modest houses and even small standalone structures like granaries. With its characteristic layered interlocking of wood-and-stone, topped by slate roofs, the kath-khuni buildings are easily recognizable. The technique relies upon a limited range of materials which, in turn, has evolved into a distinctive aesthetics of hard and soft materials, of cold and warm colours, of rough and smooth textures.

Fig. 2: A typical one-storey house in Gavas

Fig. 3: A five-storey tower temple in Summerkot

Fig. 4: A two-storey darbargadh in Sainj

Fig. 5: A free standing granary in Chitkul. While different in scale and use all the buildings show the typical and recognizable components of kath-khuni buildings.

Some houses and temples built using kath-khuni technique are decades or perhaps centuries old and are standing stable against all types of seismic and climatic forces. These buildings incorporate particular plan shapes and structural configurations together with use of locally available building materials and details, and illustrate remarkable insights that lend a distinct visual character of traditional construction and indigenous knowledge.

Traditional builders and local materials

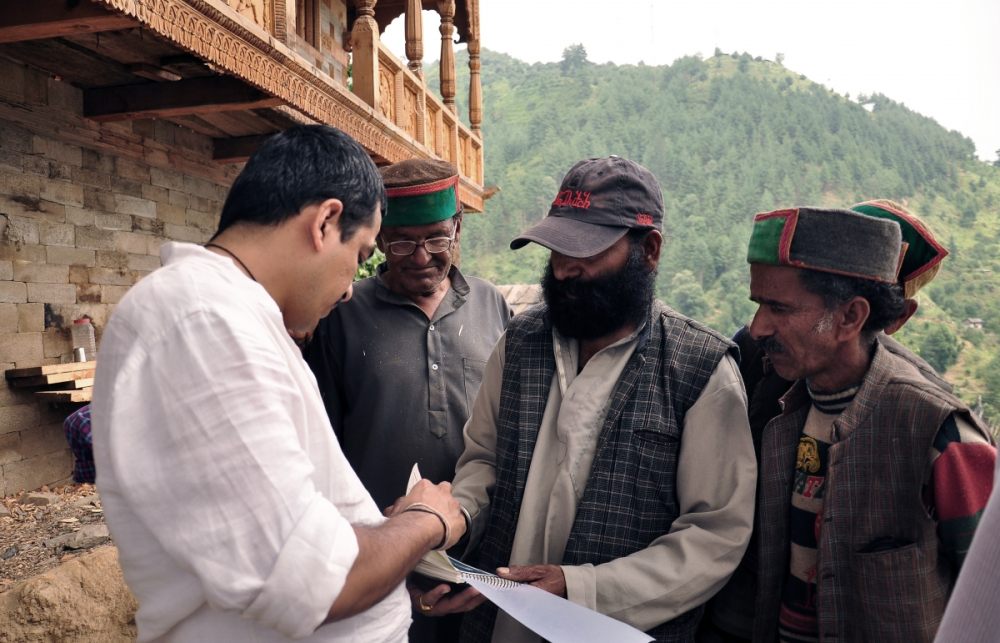

The construction of houses is largely done by hand and by the residents themselves, sometimes with the help of other residents from the same or nearby village while special artisans are employed for construction of temples or religious structures. The know-how of the building construction is passed from generation to generation in mostly oral and empirical tradition by working as an apprentice for a number of years. The mistris of Himachal are typically adept at working with wood and stone, and are a veritable storehouse of indigenous knowledge. Such knowledge may range from where to source the wood or stone, types of wood available and which ones are appropriate for either structural or carving purposes to how to cut thin sheets of singles form a block of stone using rudimentary tools and so on. Usually the entire construction is carried out manually with limited tools and the use of power-driven technology is minimal and was introduced only recently. It is the close interdependence between people, materials, making and environment that has created a lasting architectures specific to the needs, climate, place, and culture and that evokes a sensation that is special and spiritual, beyond the materiality.

Fig. 6-9: (Top to bottom) The supervision of temple construction is headed by a master craftsman who is chosen by the village head with consensus of the residents; he is often identified as the vishwakarma, according to the Hindu belief system. Above are photographs from the temple construction site at Devidhar village; Interaction with the master craftsman; Craftsman engaged in woodcarving.

Fig. 10 & 11: Top: Himachal Pradesh is rich in timber that is especially strong and long-lasting and is therefore the predominant material of construction. Deodar is easily recognizable with its long trunk, spreading branches and dark green foliage. Bottom: Cross-section of deodar tree

The primary materials of construction are wood and stone for wall and plinth, topped by slate shingles. Wood is predominantly from the Cedrus Deodara (Deodar/Devidar) an endemic species to Western Himalayas and one of the strongest of Indian conifers. It has straight veins and grows upto 50 metres. Being very durable, it is used in structural work of all kinds. A well-known folk saying is that this Himalayan wood will last for 1,000 years in water and five or ten times that long in air.

These materials (stone, wood and slate) are locally available and possess specific properties that make them excellent choices for building construction from sustainability and performance perspectives.

Indigenous construction: Kath-khuni

A typical house in Himachal is usually two or three-storey high while a temple may rise much higher from a single storey to a tower with seven storeys. However, the method of construction and elements remain similar in most cases. The level of articulation and detailing is far more intricate and elaborate in temples. In the houses, usually the ground floor is used for keeping cattle and the living areas are on the upper floor.

Typical construction begins with preparation of the ground; the trench is dug relative to the height of the structure, which is then filled with loose stone blocks which rise up to make the plinth. The raised podium provides the stability to the house or tower and also protects the building from snow and ground water.

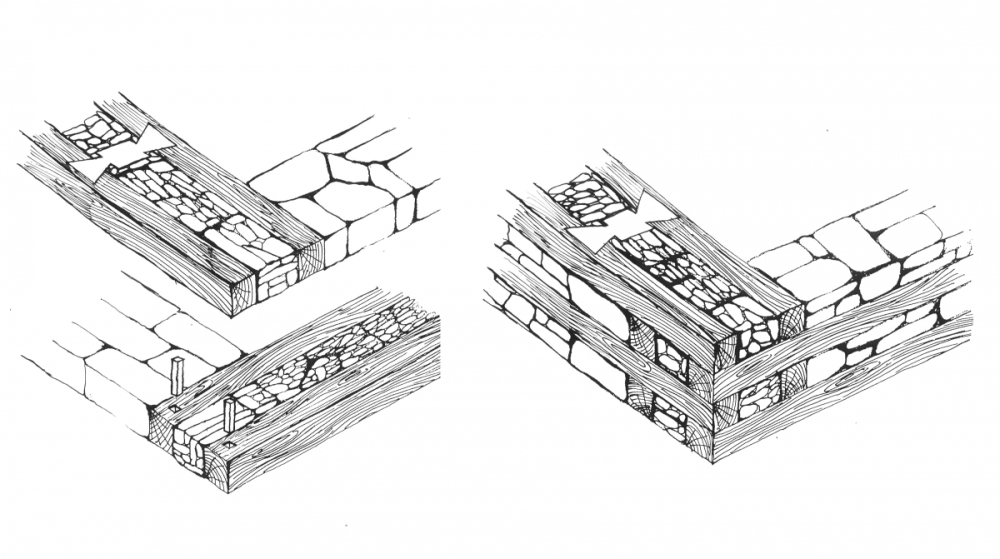

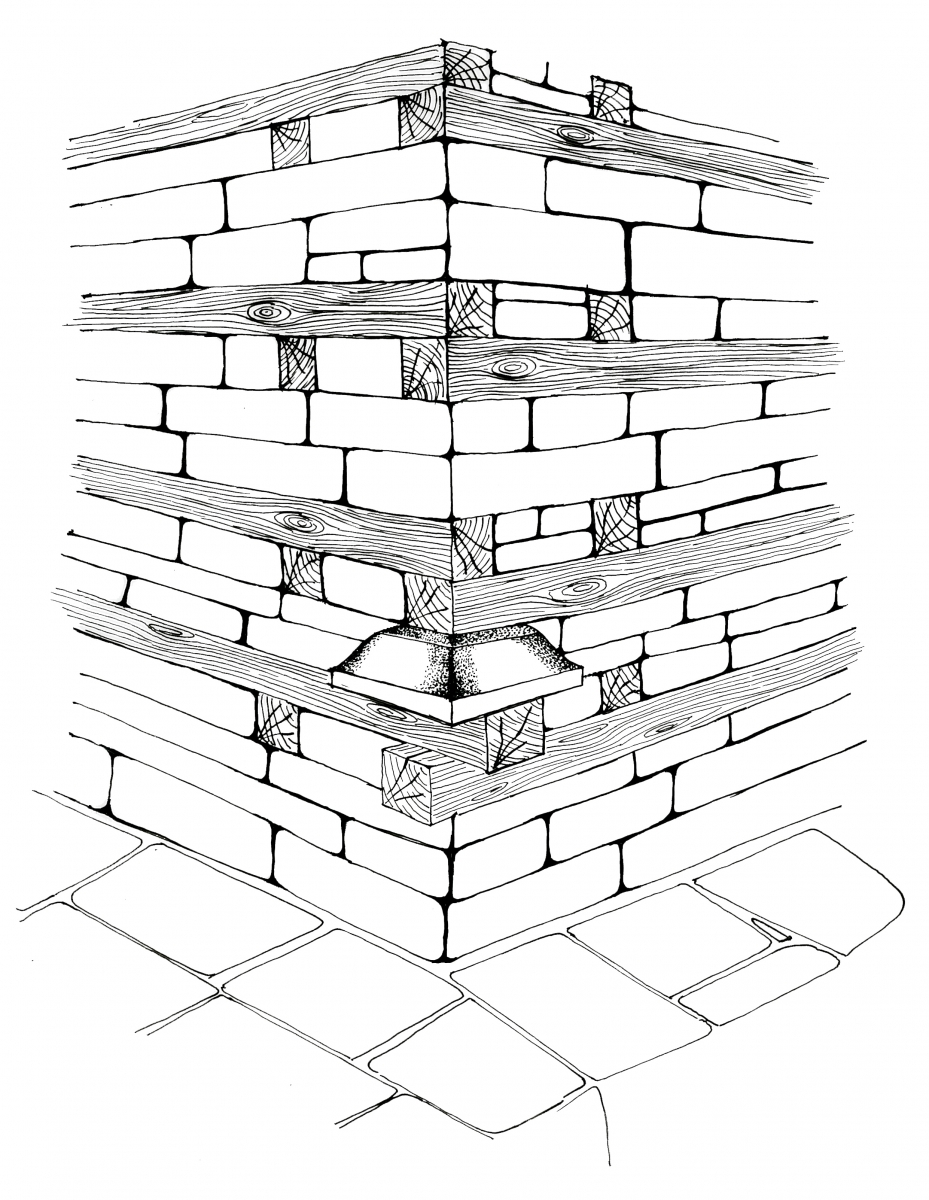

It is followed by construction of double-skin wall made with alternate courses of dry stone masonry and wood without any cementing mortar. It involves laying two wooden beams longitudinally parallel to each other with a gap in-between. Loose in-fill material is packed as filler and the external and the internal skins of the walls are held together by cross braces or dovetail called maanvi. This layered construction of wood-and-stone is more distinctly visible at the wall corner and forms the quintessential feature of kath-khuni houses. As the walls rise higher, stone courses decrease and the wood sections gradually increase. The heavier stone bases carry the lighter wooden structure at upper levels. The surface is usually plastered for internal walls with mud.

Fig. 12 & 13: A kath-khuni wall is constructed by laying two wooden wall beams longitudinally parallel to each other. This defines the width of the wall. The edge members are lap jointed and secured by a kadil (wooden nail). This arrangement of alternating stone and wood add flexibility and has proved to be a good safeguard against frequent seismic tremors.

Fig. 14-16: Images of wall construction at Devidhar village, which show the dry masonry construction with in-fill and lap jointed members at the corner.

The next space integral to the house is the cantilevered balcony, projecting either on one or all sides of the structure, which rests on the wooden beams fixed in the wood-and-stone walls. A wooden roof frame tops off the structure and is covered with locally available slate tiles. The basic structure of the balcony is secured in walls and details such as parapets, fascia boards and panels are incorporated later. Balconies used to be open but with the passage of time, various forms of enclosures are now observed. The supporting wooden posts also support the roof structure, in many cases are molded and richly carved.

Fig. 18: Corner detail; wooden members are notched and lap jointed so that they intersect at the corner and further supported by cantilevered member fixed at one end in the wall.

The last phase of construction is the roof which is made to rest on wooden beams followed by purlin and rafters, it has substantial overhanging and is covered with slate stone or wooden shingles. The geometry of the roof is usually pent and gable but several variations are observed. The pitch and geometry of the roofs changes as one climbs to higher altitudes in Himachal Pradesh. The completion of the roof is marked by laying the ridge beam.

Fig. 19 & 20: Houses showing pent-and-gable roof finished in slate stone in proper rectangular shapes and the image on right shows randomly shaped stones arranged in a house in Janog village.

The construction from foundation to roof uses no mortar in the courses of stone; the sheer weight of dry masonry and the roof in slate stones holds the structure down in place. Traditionally no metal nails were used in wood courses instead strategically inserted wooden braces and joints held the structure together. Nail-less framework without rivets and not rigid construction allows the building to flex with the seismic waves and effectively dissipate the energy of earthquakes.

Aesthetics of craftsmanship

Fashioned out of a limited palette of materials, tools and construction techniques, the indigenous houses of Himachal reflect not just remarkable thematic unity of material practice but also exhibit a range of creative details from wood carving, joinery, surface articulation, door handles that are all an integral part of building construction. Each detail is justified functionally which shows the material sensibility and ingenuity in handling. They are reflected in the rhythmic pattern of wood and stone on the façade, on doors and windows, and on the overhanging balcony, that float lightly on the stumpy base, adding another texture and dimension to the otherwise dynamic massing.

Fig. 21 & 22: The appeal of indigenous building is very striking and a modest home has a range of details besides the construction systems that qualify for attention which shows the existence of a strong craft base.

Wood carving

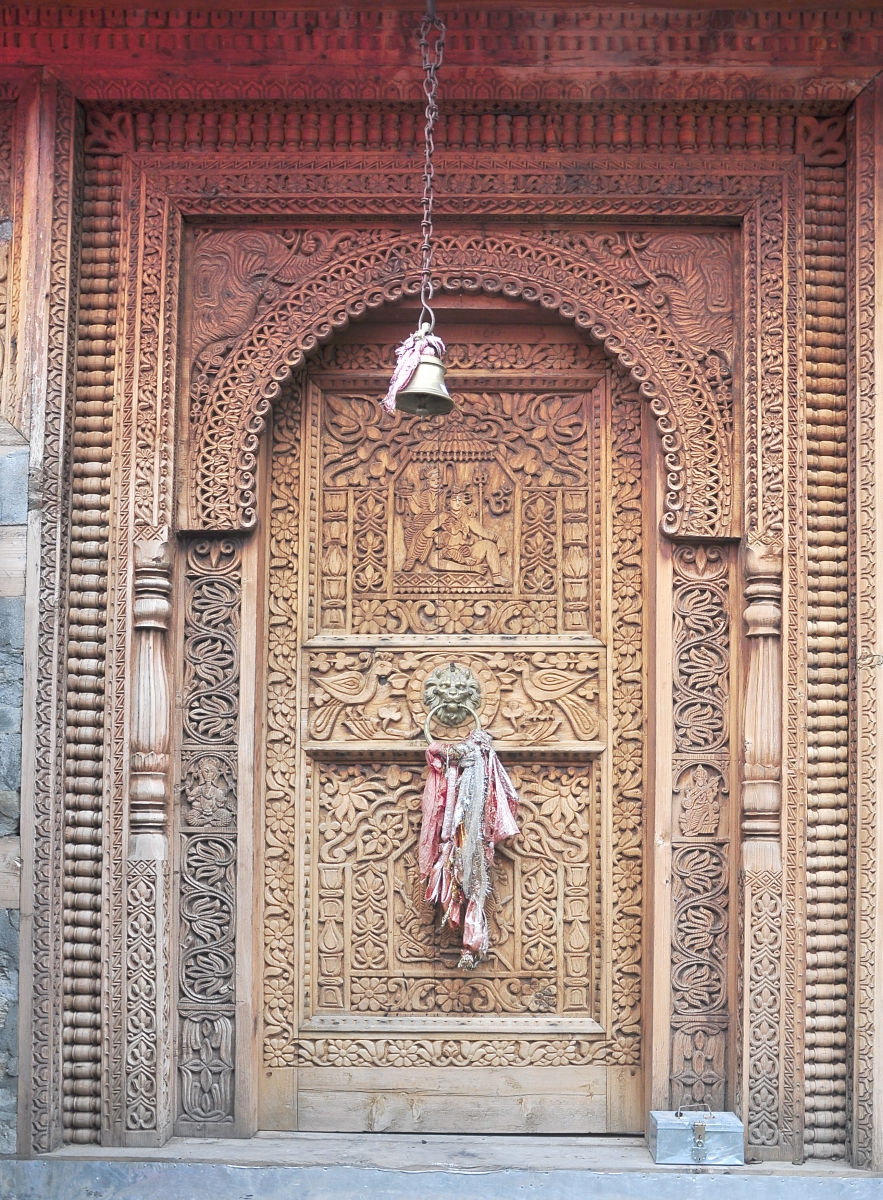

Wood carving is an integral part of kath-khuni built forms and is the oldest craft of Himachal and still thrives in a number of valleys. The quality of wood carving reflects high level of intricacy and skills, as well as a highly developed aesthetic sense that fluidly integrates and expresses motifs based in folk tradition and religious references. The jhalars (wooden pendants) along the roof edge, motifs on panels and on walls and balconies, door frames and windows all are intricately carved. The themes range from folk to abstract to geometric to natural ones. They are used as standalone motifs and at other times as a part of a continuous frieze or panel. Wood-carving is also seen in kath-khuni houses, though usually not as elaborate as that in the temples of Himachal, crude carving on the door frames, balconies and ridge can be seen in many houses.

Fig. 23-25: In temples, the exposed surfaces of wooden beams along the width and cross-section at the corners provide manifold options for creative woodworking details and carvings. The decorative motifs range from floral, animal, mythic characters, or narratives of epics as discrete elements or in a running freeze. The carvings may be done directly on the wooden beam or on a panel that is then fixed on to wooden beams. The end sections of wooden beams at the corner sometimes jut out and are finished in carvings, at other times they are finished as beautifully carved volutes.

Fig. 26 & 27: Examples of wood-carving on the openings at temple at Devidhar and Summerkot. The wall punctures such as doors and windows are the most ornamental elements in hill architecture. The sizes of the openings are relatively small and are articulated within the horizontal tie beams.

Fig. 28: 'The essential tool kit of a traditional wood carver includes chisels, hathodi (hammer), punch tool, and basola (adze). The metal parts are fabricated by the local blacksmith and wooden handles by the wood carver' (Matra 2008). Most common wood-carving technique involve relief carving (high to low) which is applied to friezes, panels, entablature and other planar surfaces. Sculptural carving is utilized in making columns, studs, doors, frames, hanging pendants and beam edges.

Wood joinery

Apart from woodcarving, a remarkable level of woodwork details can be found in many parts of Himachal. What otherwise can be an ordinary wooden joint in a door frames evolves into a complex play of interlocking volumes and fluid edges. Some other details follow regular geometric curves, other follow free toothing patterns. These wooden joints in all likelihood without the use of nails flex just enough to rock with the earthquake tremors but otherwise remain tightly locked together. The various kinds of joints seen are the lap joints at balcony junctions, extension joints in the wall beams, ‘z’ joints in the floor boards, maanvi (double dovetailed joint) in the wall, splice joint with wedge in structural walls. All of these evolved out of a functional need and yet are highly expressive.

Fig. 29-31: Details of joinery. The joinery reflects sophisticated skills of indigenous craftsmen. The strength of these joints lies in the interlocking method of connection where the wood itself prevents movement.

Conclusion

The indigenous buildings of Himachal Pradesh reflect a remarkable understanding about appropriate use of local materials, construction techniques and joinery details that stand strong against the climatic and seismic forces of nature. The intricate interlocking of joints without nails is the hallmark of indigenous construction ingenuity. The construction, society, values and building knowledge are continuously transforming, new materials are replacing the old. With this change, there is also an uncertain future for indigenous practices. This article in a small way tries to capture the broad spectrum of details and construction that can help sustain the local building practice that is worth appreciating, documenting, and preserving for the future.

References

Bernier, Ronald M. 1997. Himalayan architecture. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; London: Associated University Press.

Handa, O.C. 2009. Himalayan Traditional Architecture. New Delhi: Rupa & Co.

Thakkar, Jay & Morrison, Skye. 2008. Matra: Ways of Measuring Vernacular Built Forms of Himachal Pradesh. Ahmedabad: SID Research Cell, CEPT University.