An appreciation of Ladakh’s history would be incomplete without an understanding of its relationship with the areas and regions in its immediate neighbourhood—Kashmir and Baltistan to the west, the vast expanses of Sinkiang/Xinjiang and Western Tibet to its north and east, and the Himalayan range in the south. Over the centuries, each region has exercised different degrees of social, cultural, economic and religious influences upon Ladakh. These influences, as we will see, are reflected in the rock art/petroglyphs of Ladakh.

The credit for the first scientific documentation and descriptive articles on the rock art of Ladakh goes to the Moravian missionary scholar August Hermann Francke (1870–1930), who was based in Leh and Khalatse between AD 1896 and 1914. A decade later, Filippo De Filippi’s account of his travels published in his book[1] mentions the petroglyphs near Khalatse. Likewise, there are several more passing-by mentions of petroglyphs by various travellers, not very significant academically, except for their existence. Another decade later, Nicholas Roerich, the famous Russian painter, writer and theosophist, also mentions rock art in his book[2], when he was in Ladakh in 1925. The well-known geologist, anthropologist and explorer-writer Helmut De Terra, was a member of the German-Swiss expedition (1927–28) to the western parts of Central Asia. In an article[3], De Terra provides us with a photograph of a cave in the Nubra Valley along with a description of the ibex/deer-hunting scene carved on the cave walls. In 1930–31, the renowned Tibetologist Prof. Giuseppe Tucci visited Ladakh. In his book[4], he mentions that he visited Khalatse in search of the boulder with the Kharosthi inscription of the Kushan King Vima Kadphises.

Ladakh’s closure in 1949 for the next quarter-century ensured no further attention to rock art from foreign and Indian researchers up till its reopening in 1974. In the following two decades, efforts by several domestic and foreign researchers expanded the two dozen or so known sites to include those from other regions of Ladakh, and papers on significant sites from places including Alchi, Tangtse, Zamthang and Khalatse were published in travel books and academic archaeological journals. A good example is that of Tibetologist, explorer and travel writer Michel Peissel, who visited Zanskar in 1976, shortly after it reopened, and devoted an entire chapter on prehistoric rock art, titled ‘A stone-age artist’, in his book[5].

Travelling in Ladakh at about the same time, David Snellgrove and Tadeusz Skorupski published their scholarly research in an excellent book[6]. Although the book focuses on the historic period of Ladakh, there is a useful section on rock art accompanied by pictures of petroglyphs from Alchi. Notable amongst the more scholarly and academic research was the publication of the Rock Art of the Old World, published by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA)[7], which included an article titled ‘Archaic Petroglyphs of Ladakh and Zanskar’ by Francfort, Klodzinski and Mascle. Based on stylistic and other considerations, the authors proposed linkages between petroglyphs found in the Steppes of Central Asia circa 1000 BCE and similar images found in Ladakh. In two notable articles by B.R. Mani[8] we are provided with an updated map of Ladakh on which the rock art sites surveyed were depicted. His survey of rock art has included almost all regions of Ladakh, and many of the petroglyphs are described in detail and accompanied by photographs. Notable contributions have been made by Mr Martin Vernier, an independent Swiss scholar from the mid-1990s to the present time, who has systematically documented over 10,000 petroglyph images from over 100 sites. Since then he has collaborated with other researchers, notably Laurianne Bruneau, and they have expanded the number of known sites to over 150, and the number of petroglyphs to about 20,000. Bruneau and Bellezza’s publication[9] throws a significant light on the comparative study of the two regions. Dr Quentin’s Series of publications on historic sites in different regions of Ladakh has a significant portion on the petroglyphs of Ladakh.

At present, the author along with Mr Viraf Mehta, Dr Quentin Devers, Sonam Choldan Gasha visited almost every one of these sites as a part of their own travels and researches to the remotest corners of Ladakh, and it is our view that there are a significant number of as yet undiscovered prehistoric rock art sites awaiting further research and documentation. As of 2020, the team has recorded more than 400 sites spread throughout Ladakh. A testament to this is the recent discovery of the authors in 2013, of extremely rare pictographs of deer, sheep and other animals painted on the walls of a rock shelter down the Indus River from Domkhar village. Additionally, the authors have found several previously unrecorded sites and petroglyphs across Ladakh, for example, along the Gya Chu near the village of Meru and Lato, near Santak in Lower Ladakh, at Chalunka village in the Nubra valley, several sites along the Kargil-Kharbu route, a site near Shayok village, several boulders en route to the Gotsa nunnery beyond Mahe, a single boulder at Hanle, sites along the Suru valley and boulders near Dzongkhul Gompa in Zanskar.

Distribution of Petroglyphs in Ladakh

Rock art of Ladakh depicts varied compositions such as figurative and realistic engravings, along with unrealistic and indeterminate forms. Subject wise, the entire collection may consist of various representations of animal, human and various other motifs and forms. Thematically, it may represent an isolated lone figure to complex interrelated figures comprising humans, animals, signs and symbols amongst others, of hunting scenes, fighting and dancing. In other words, the petroglyphs of Ladakh show a diverse nature of engravings in all possible forms. They are also distributed in all the regions of Ladakh in the various valleys and mountain systems.

The figurative and realistic figures include animal and human forms. The wild figures would include dong or yak (usually depicted with a hairy body and bushy tail), wild sheep (horns curved back or sideways), ibex (horns serrated and curved back and upward), stag or deer (with antlers), tigers or leopards (or felines with their jaws open), elephants, birds, lizards and snakes. Domesticated animals include horses (raised mane), camels (double humped), dogs (tail curled on the body), amongst others. Social events such as hunting, fighting, dancing and unknown group activities are also depicted.

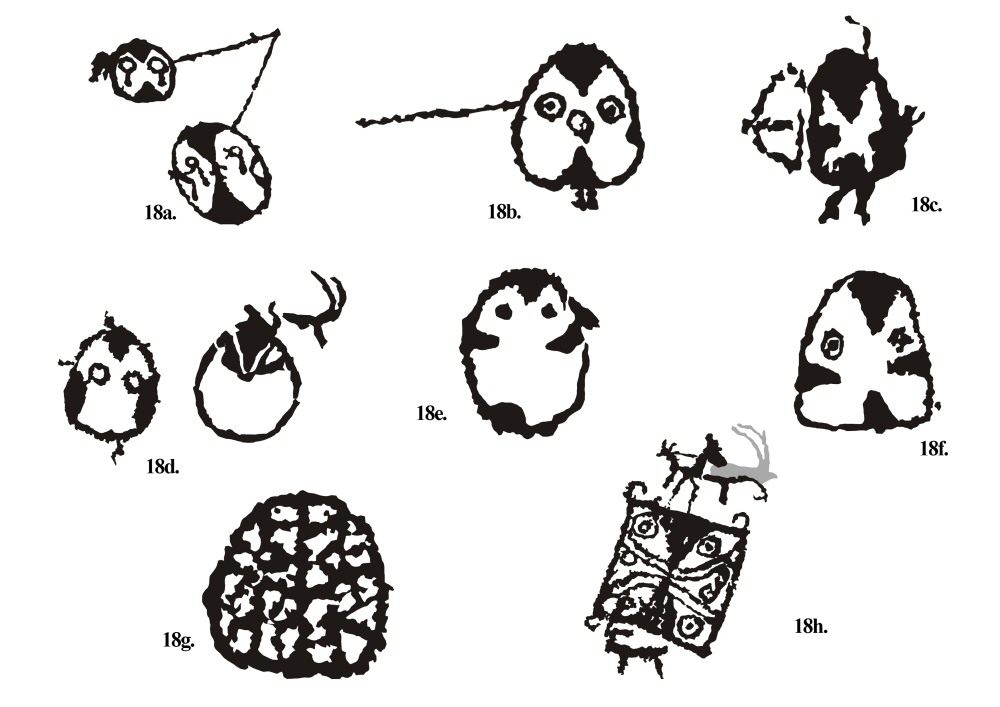

Another important and major class of representation consists of engravings in unrealistic figurative forms including some indeterminate ones. Such figures may consist of anthropomorphic forms, disproportional human forms or human forms with certain parts exaggerated, animal-human conflations, strange signs and symbols associated with some scenes. As such, these figures convey more than mere figure of human or human-like forms. Anthropomorphic figures, whenever discovered, are usually found in particular sites and often in association with vast numbers of other similar depictions. Mask-like figures, of late, have been found in plenty, particularly in the Nubra valley. The more uncertain and indeterminate forms include geometric decorations, zigzags, meanders, concentric circles and combinations thereof.

Ladakh may be divided into several regions, with each region settled in a different river valley system. For example, the Sham region along the Lower Indus River, Nubra region along the river Shayok, Changthang spread along the Upper Indus River and beyond, Kargil along Suru, Dras and Wakha Rivers, Zanskar along the Zanskar River. Interestingly, each region had their own principalities in the historic past and also a different culture and dialects.

The rock art of Ladakh, as said earlier, now consists of more than 400 sites. The diversity in style, subject and distribution are enormous. A site may consist of a single engraved boulder to hundreds of engraved boulders. For example, the Ensa site in Nubra

Petroglyphs along Upper Indus

Indus stretches from Demchok in the northeast to Batalik in the west, running about 500 kilometres through Ladakh. Coincidently, most of the early trade routes pass along the Indus and as such most of the petroglyphs are found along this river. However, the distribution of rock art gradually increases in frequency as we go westward. Altitude and geography may have played a role in human endeavour in these mountainous regions. Therefore, we divide the stretch of the Indus as Upper Indus and Lower Indus, Leh being the midpoint. The rock art of Upper Indus (which largely lies in Changthang region) mainly represents wild animals, hunting scenes and some rare unusual forms. While the rock art of Lower Ladakh shows more diverse forms and the variety increases both in subject and style.

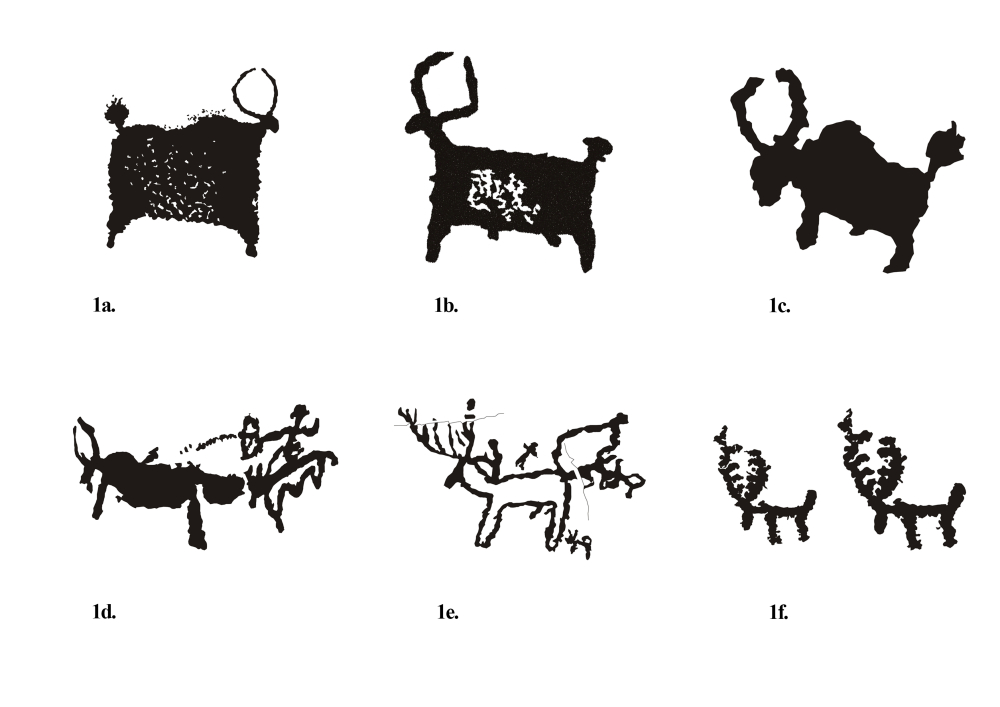

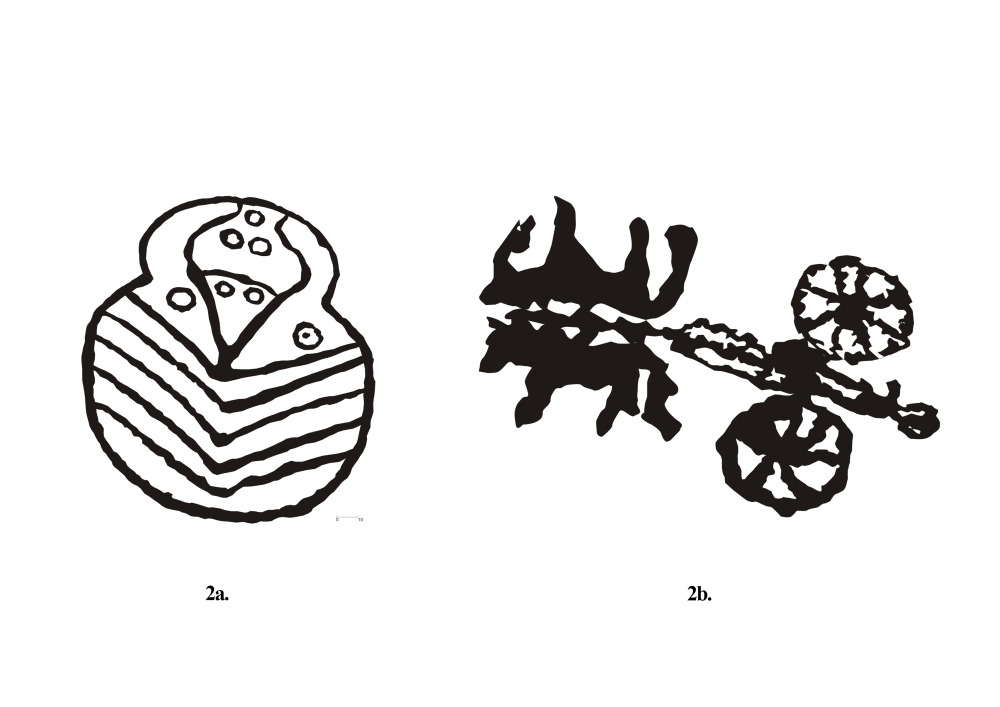

Many of the species of the rock art of Upper Indus shows figures of yak, deer and wild sheep, often being hunted. (Fig. 1) While yak and wild sheep are a common species of Changthang even today, deer seem to have been a species that may have existed in the past. Rarely, there are some unknown figures as seen on the Shara site. (Fig. 2a)

Petroglyphs of Lower Indus

Rock art along the Lower Indus is extensive. However, only some of the rare and representative forms are discussed here. The sites of the Sham valley along the lower Indus, primarily downstream from Saspol, is one of the most concentrated petroglyph sites of Ladakh. This is spread for more than 150 km, all along the Indus. One of the most interesting sites, and probably one of the best maintained, is at Domkhar. The site near Alchi also shows human figures with undetermined figures. (Fig. 3) The stylistic figures of the human forms are very peculiar to this isolated boulder.

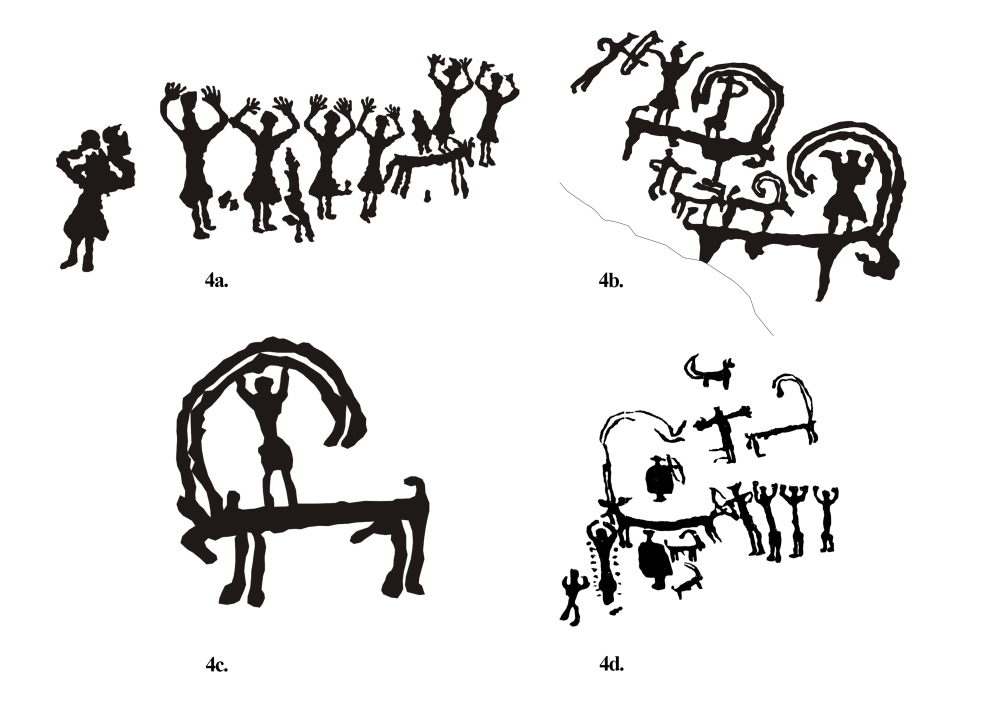

Between Skyurbuchan and Achinathang, at another desolate site, on the right bank of Indus, are examples of the most intriguing figures. One of them seems to be a ritualistic figure consisting of several human beings with raised hands. (Fig. 4a) The figures depicted are incomplete, as the boulder is partially buried under the debris of the road construction. Nearby, there are several more figures showing a rare representation of animal-human conflation (4b. and 4c.). Near Skyurbuchan there is another site with scores of figures, much of it has been vandalised with names and figures. (Fig. 3d.) Recently, it has been partially damaged for want of rock for construction. One of the scenes shows a hunting figure associated with several other figures. One of the human figures has dots around the body, another with a rounded body, and a few more with raised hands.

A site near Hanu Thang has one of the most puzzling assemblages of petroglyphs. On a very large boulder measuring approximately 30 feet wide, the base touching the river bank. The entire rock face is covered with hundreds of figures engraved on it. (Fig. 5) Many of the figures are part of hunting scenes, while an equal number show social scenes with strange human forms along with anthropomorphic figures. Some of the animals forms are stylistically very different. In one corner of the boulder are a couple of Kharosthi inscriptions. Nearby, on another boulder is a flat rock with an outline of a human figure. A short distance above this is a few more boulders, a couple of them showing giant-like figures with stretched hands and some foot and handprints.

In Dargo, on the left bank of the Indus, there is an assembly of one of the strange anthropomorphic forms on one single boulder (Fig. 6), once again this boulder shows a unique stylistic and thematic scene.

Domkhar Sanctuary

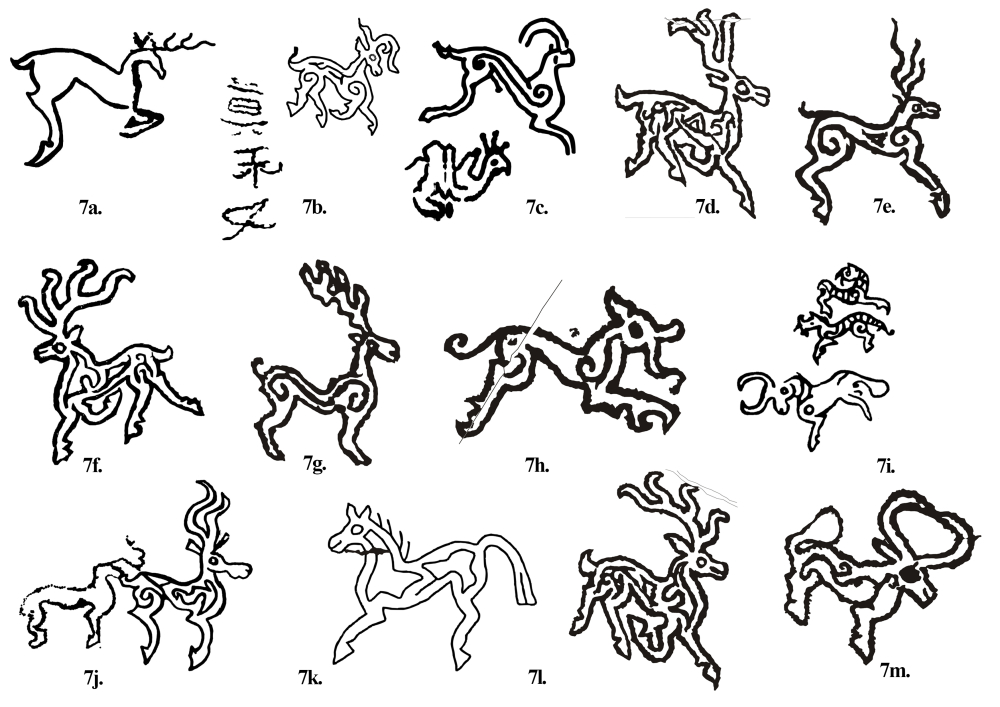

Domkhar village, about 112 km from Leh, an important site in Ladakh, contains one of the finest collections of rock art, both in artistry and antiquity; hence, it is called Domkhar Sanctuary. The foremost subject of the site is the ‘Animal Style’ figures, in their extreme beauty and perfection. These figures generally consist of elegant curves and spiral hooks, many of the animals appear to be poised on the tips of their hoofs. (Fig. 7) At least in Ladakh, there is no comparison to the site both in terms of beauty and diversity.

Outside Domkhar, there are a few more sites in Ladakh where we find ‘Animal Style’ figures. Such figures are distributed randomly all along the Indus including Kairy, Shara, Kharu (Fig. 8), and Khalatse. One of the most prominent one is a boulder in Tangtse showing what appears to be animals in a pursuit scene, resembling one reported from Rudok (in Tibet). Besides the Indus belt, such figures are also reported from various sites in Nubra, Zanskar and Kargil.

It may, therefore, be assumed that the artists who engraved with this stylistic behaviour travelled well into the remote valleys of Ladakh, besides moving primarily along the Indus.

Petroglyphs of Changthang

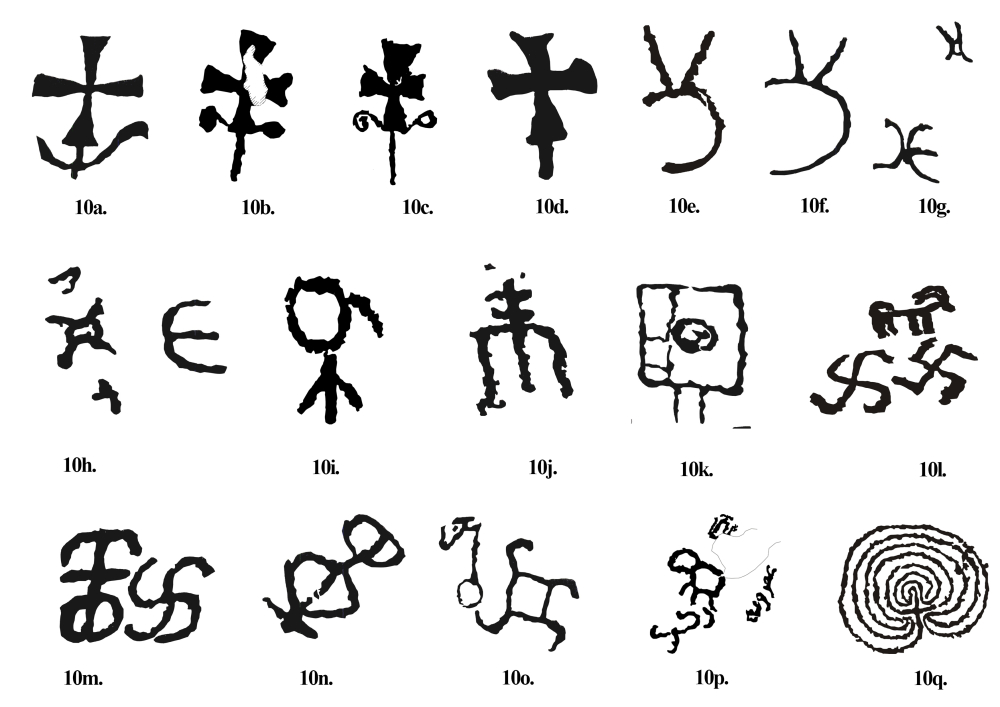

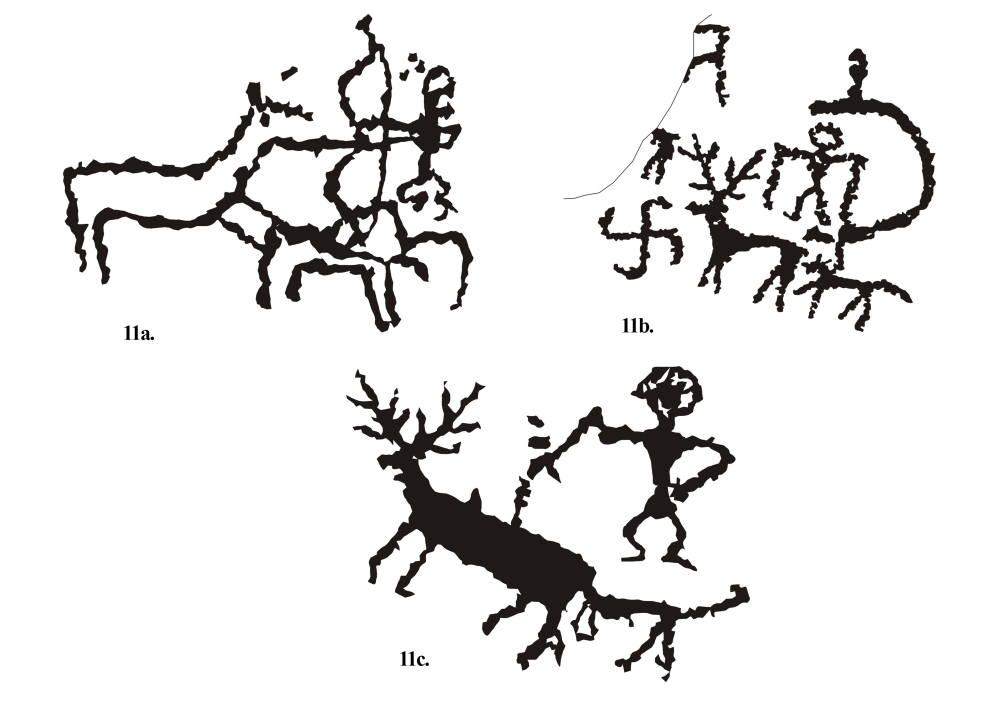

Petroglyphs have been found comparatively less frequently in the Changthang region. Tangtse is one of the largest settled villages of Changthang. Historically it falls on one of the trade routes towards Tibet via Rudok and Gartok. Understandably, it shows one of the finest collections of rock art with signs and symbols as well as a good number of inscriptions. The site is also one of the most studied ones. There are three main boulders, about the size of a large room, in the middle of the village. These boulders are covered with hundreds of carvings, particularly with many types of signs and symbols. (Figs9 and 10), including some hunting scenes (Fig. 11). There are also inscriptions in various scripts.

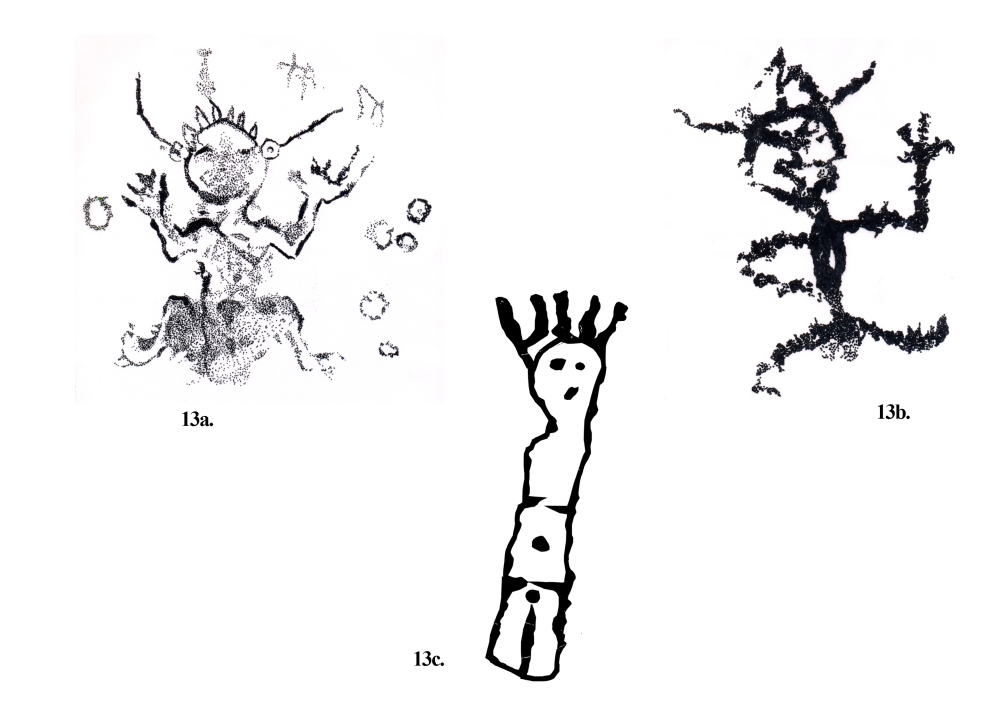

Around the village, there are several more boulders with an equally interesting number of carvings. One of the finest is the predator chasing prey scene (Fig. 12), a similar figure found in Renmudong, Tibet, dates to the Iron age (Wu Junkui, Zhang Jianlin, 1987). The other boulders around the Tangtse village show some interesting anthropomorphic figures. (Fig. 13)

Petroglyphs of Nubra Valley

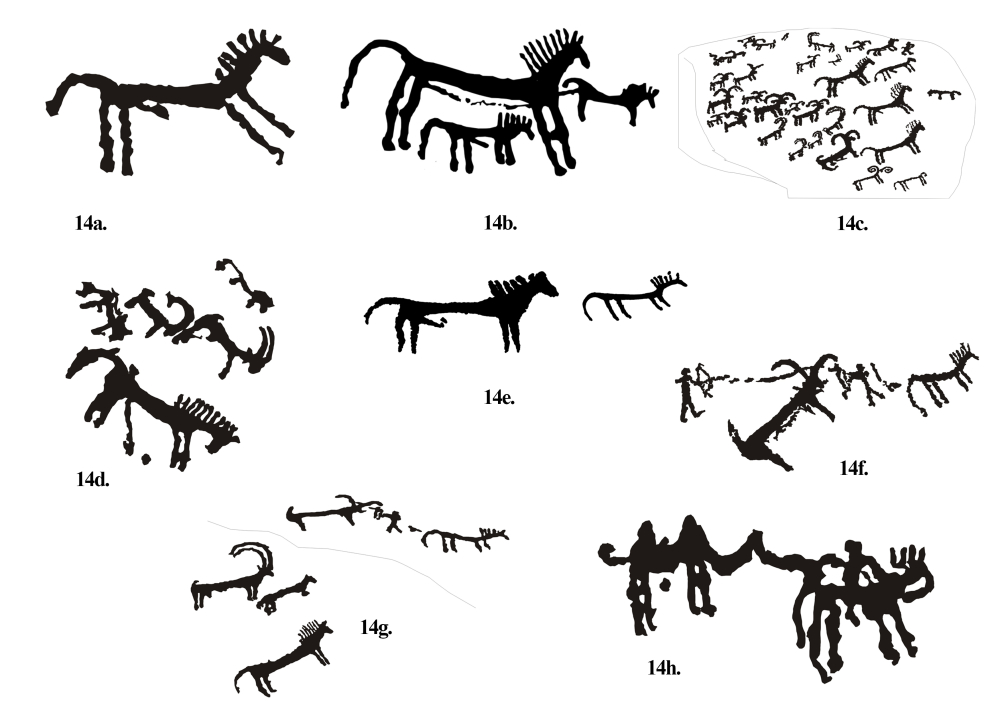

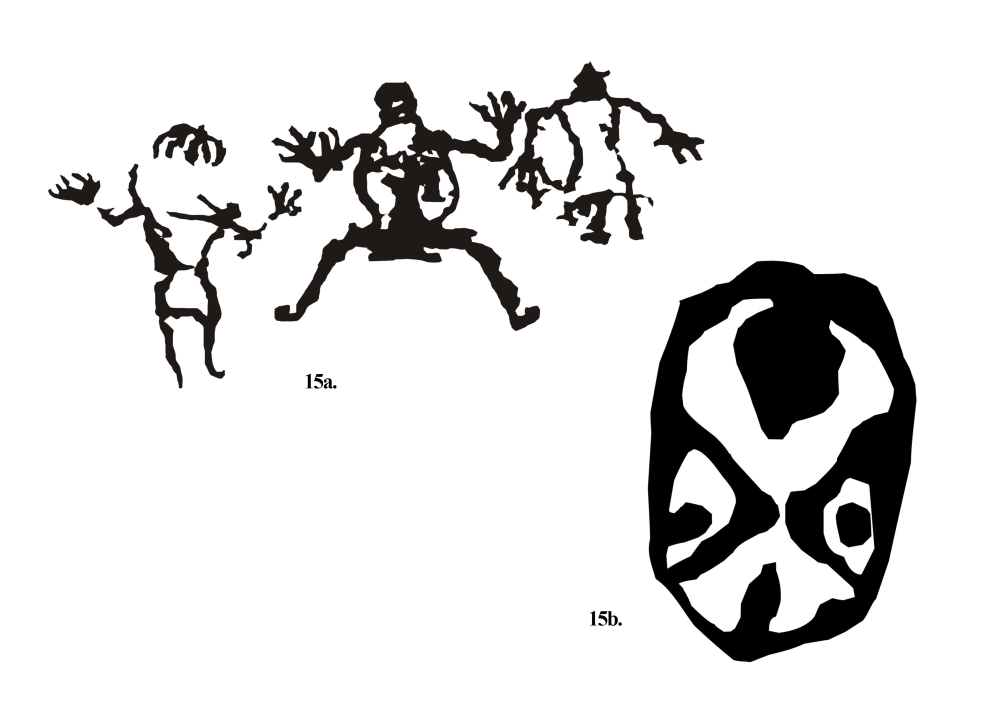

One of the major trade routes connecting Ladakh to the Silk Route came through the Nubra valley, via the Karakoram Pass. It was near Sasoma village, on the left bank of the Nubra River, where traders stopped before they began the long and arduous journey to Yarkand. Near Sasoma there are, quite understandably, several sites with engravings of horses and camels, the beasts of burden on this trail. The stylistic representation of the horse with raised mane and with male organs is very typical of the site. (Fig. 14) Few more boulders around depict the anthropomorphic forms in a form of ‘giants’ and another with a mask-like figures (Fig. 15)

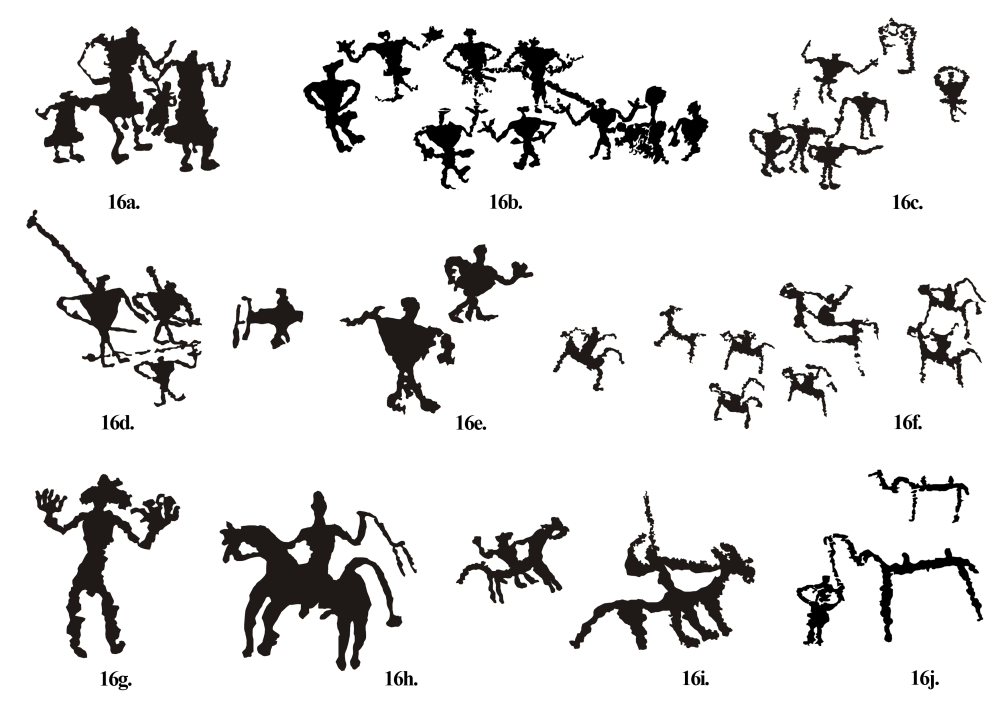

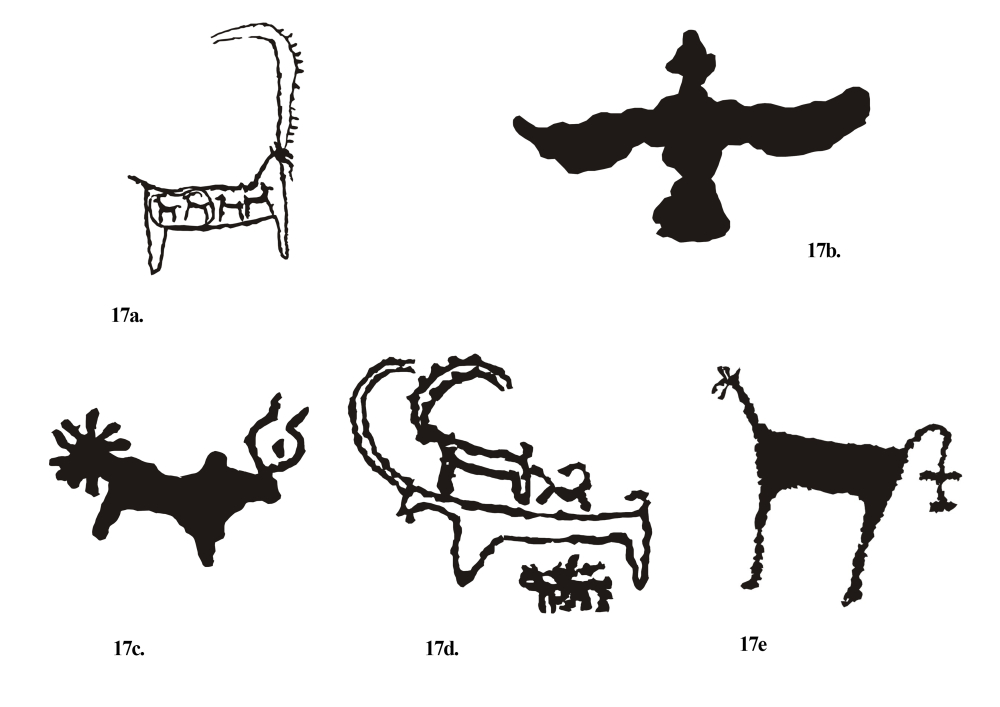

Another site of interest is at Ensa, around the Murgitokpo (stream), on the right bank of the Nubra River. It has the largest collection of petroglyphs in Ladakh. The site is a conglomerate of thousands of blackened boulders, with hundreds of them having carvings. The entire site is cut by the Murgi stream, in fact when the stream is in full force, it flows all around the site, endangering the site. The human forms with broadened shoulder are peculiar to the site. (Fig. 16) Some figures of animal forms are also specific to the site. (Fig. 17) Mask-like figures are found in plenty at Ensa, making the site one of the most intriguing in the depiction of form, style and theme in the rock art of Ladakh. (Fig. 18)

The enormous number and peculiar stylistic representations at Ensa site are puzzling particularly from the standpoint that the site is not immediately along any of the trade routes and neither does it provide much grassland for pastoralists. Even the present villages on the right side of the Nubra River are squeezed between the river and the mountain with very limited land.

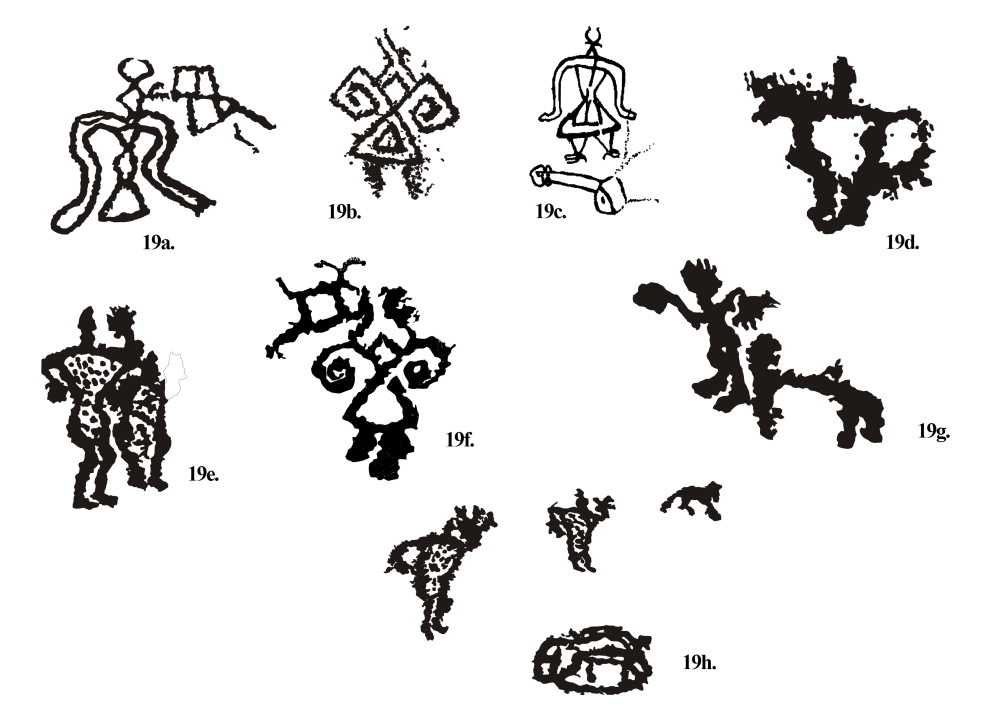

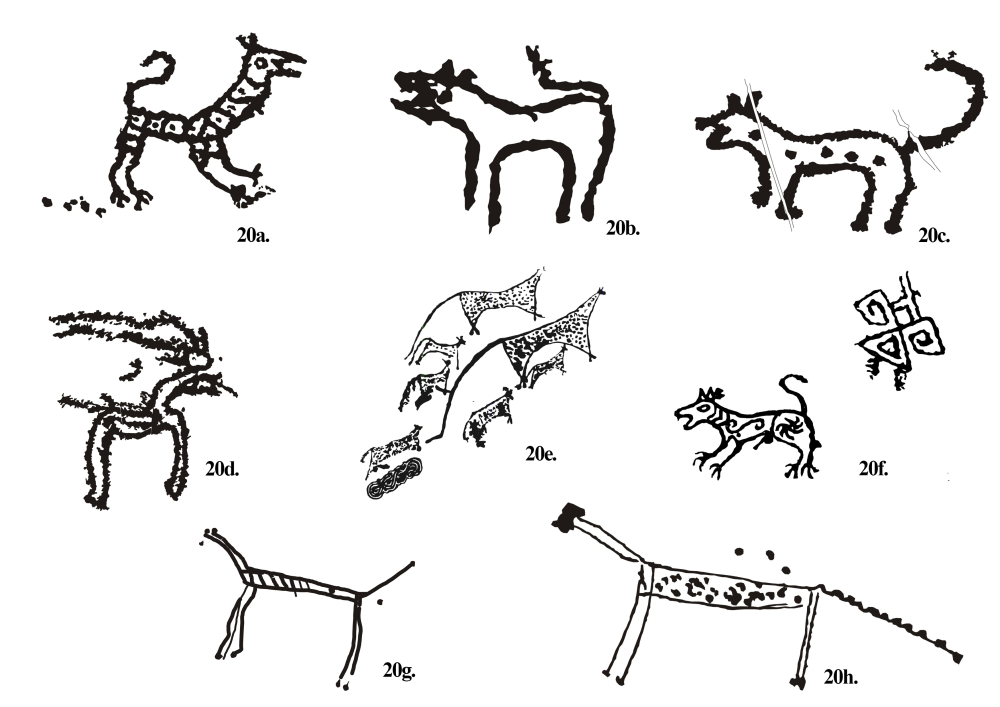

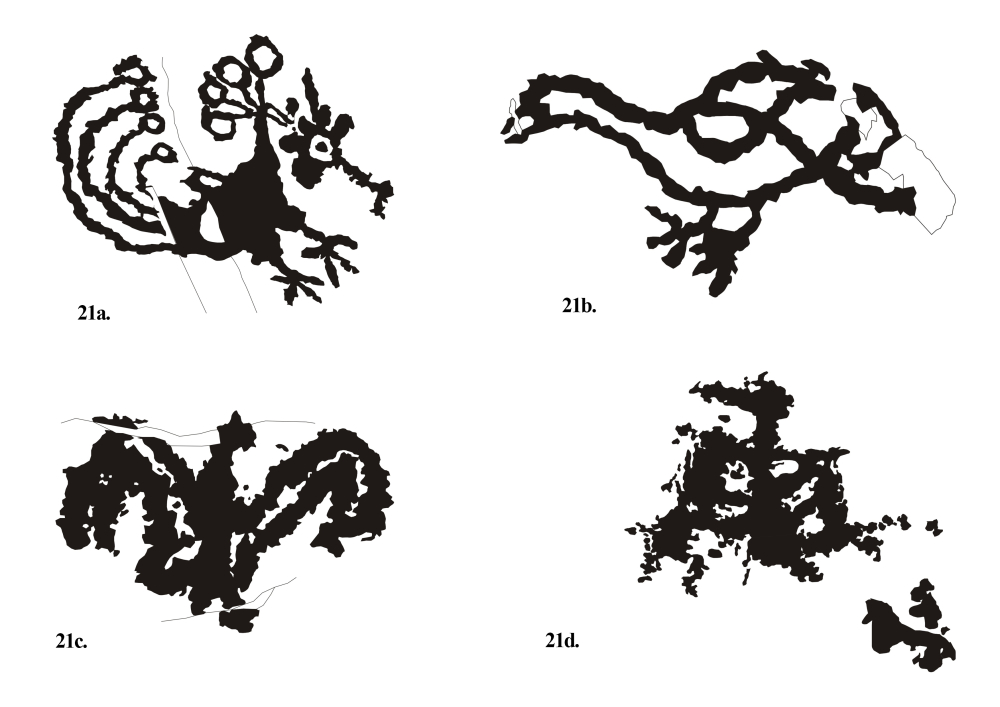

Petroglyphs of Chilling Valley

Chilling valley lies along the last stretch of the Zanskar River before it meets with the Indus River near Leh. Much of the later part of this river, which cuts through Zanskar Range, forms a deep gorge, impassable along the bank. There are about six sites along the last stretch of the river, covering a span of about 25 kilometres. There are several trade routes passing through the valley, before it narrows down, leading to smaller villages on the northern face of the Zanskar Range. Despite many common elements, it is quite interesting to see that a significant number of the rock art figures of this valley do not show many similarities with other sites in Ladakh. Some of the human and anthropomorphic forms (Fig. 19) are once again specific to the site, likewise some of the animal forms including some felines (Fig. 20)are also peculiar to the site. The last two figures show a line drawing through sketching which is different and rare compared to the drawings done through pecking. Some of the birds or bird-like figures are also exclusive of the site. (Fig. 21)

Conclusion

While petroglyphs of Ladakh have been studied by scholars or finds mention in travelogues for more than a hundred years, serious research on the rock art of Ladakh has begun only recently. Geographically, since Ladakh has been at the crossroads of India, Central Asia and Tibet for ages, the rock art of Ladakh has a very diverse nature in terms of subject, theme or style. While the eastern part of Ladakh shows elements with more affinity to the Tibetan influence, the Western or Northern regions shows elements more common to Central Asia. However, it may be noted that despite the fact that many of these figures show affinities with other regions, a majority of them show peculiarity in both style and subject. One of the biggest problems in the study of rock art is the dating. Since no direct dating has been done, scholars date the rock art of Ladakh with reference to studies carried out in Central Asia or Tibet. The dates range from the Neolithic to Early Historic period with the bulk of rock art attributed to the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Since rock art is not an art to be viewed in isolation, rather it is based on belief systems, myths or legends, cultural practices, the environment, etc., rock art of Ladakh, in a sense, needs a more holistic approach in its study and research, much more than a comparative study.

Notes

[1] De Filippi, Dainelli, and Spranger, The Italian expedition to the Himalaya, Karakoram and Eastern Turkestan.

[2] Roerich, Altai Himalaya- A Travel Diary.

[3] De Terra, ‘Prehistoric caves north of the Himalaya,’ 42–50.

[4] Tucci, Stupa: Indo Tibetica 1, 52–53.

[5] Peissel, Zanskar, 38–51.

[6] Snellgrove and Skorupski. Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, 155–163.

[7] Lorblanchet, ‘Rock art in the Old World.’

[8] Mani, ‘Rock Art of Ladakh.’11-12.

[9] Bruneau and Bellezza,‘The rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh.’

Bibliography

Bruneau, Laurianne, and John V. Bellezza. ‘The rock art of Upper Tibet and Ladakh: Inner Asian cultural adaptation, regional differentiation and the Western Tibetan Plateau style.’ Revue d’Etudes Tibéaines, no. 28 (2013): 5-161.

De Filippi, Filippo, Giotto Dainelli, and John Alfred Spranger. The Italian Expedition to the Himalaya, Karakoram and Eastern Turkestan (1913-14). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2005.

De Terra, Helmut. ‘Prehistoric caves north of the Himalaya.’ American Anthropologist 33, no. 1 (1931): 42–50.

Francfort, Henri-Paul, Daniel Klodzinski, and George Mascle. ‘Archaic petroglyphs of Ladakh and Zanskar.’ Rock art in the Old World, papers presented in Symposium A of the AURA Congress Darwin (Australia) 1988, M. Lorblanchet (Dir.), New Delhi, Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts, 147-192.

Mani, B.R. “Rock Art of Ladakh, Glimpses of economic and cultural life.” (2000): 11-12.

Jettmar, Karl. Beyond the gorges of the Indus: Archaeology before excavation. USA: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Peissel, Michel. Zanskar: The Hidden Kingdom. New York: EP Dutton, 1979.

Roerich, Nicholas. Altai-Himalaya: A Travel Diary. New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1929.

Snellgrove, David L., and Tadeusz Skorupski. Cultural Heritage of Ladakh, Vol. 2.Warminster, England: Aris and Phillips, 1980.

Lorblanchet, Michel. ‘Rock art in the Old World.’ New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts, 1992.

Taddei, Maurizio. Antiquities of Northern Pakistan—Reports and Studies vol. 2. 1996.

Tucci, Giuseppe. Stupa: Indo-Tibetica. Edited by Lokesh Chandra. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, 1932.

Wu Junkui, Zhang Jianlin. ‘Xizang Rituxiangudaiyanhuadiaochajianbao.’ Wenwu 2 (1987): 44.