Abbas on Films and Film-writing

Ravikant (historian, writer and translator)

The polyglot Abbas was as incredibly prolific in his nearly half-century long filmmaking career as he was in his literary and journalistic avatars. He was also successful in carving out a niche for himself by forging a wide range of commercial, aesthetic and political collaborations in the teamwork that any film production essentially is. And as his erudite interventions, mainly as a writer in Bombay film industry, in the Film Seminar of 1955 demonstrates, he was acutely aware of the issues faced by film writers, and argued and worked for a more dignified visibility, presence and working conditions for them. He fought hard to bring the two worlds of literature and cinema ever closer. That he did it through his own films is obvious from the large number of film adaptations he made from his own stories and novels. He was also perhaps the first one to recognize the stellar role film writers had played in the evolution of a new 'artificially created' national language called Hindustani, at a time when it was being banished from State-controlled institutions like All India Radio. He was prophetic in underlying it as a ‘cultural asset and a unifying factor.’

For a politically committed writer, director and producer like Abbas, cinema was serious business, no less than ‘a school for masses’, and ‘film dialogues an important genre of our popular literature’, and thus the dialogue writer as ‘the philosopher of the common man... the bard and the storyteller of the 20th century’ had his work cut out:

In his dialogue must be distilled the wit and wisdom of the ages, the quintessence of contemporary humour, and philosophical comments on our life and times. From the bow of meaningful dialogue must fly out shafts of satire that puncture the hypocrisies and vanities rampant in our society. In his words must echo the sighs of the distressed, the laughter of the happy and the healthy, as well as the call to action of those who are impatient to go forward. In short, his dialogue must become the speech of our people, even as our films must be seen as the face of our people.

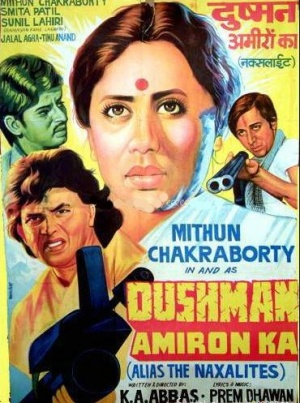

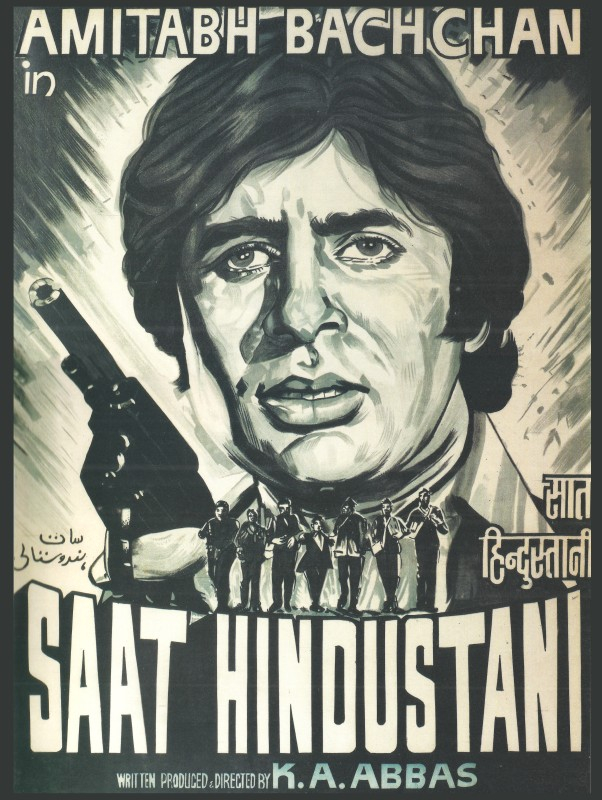

This poetic call, resonant of Marx's Eighteenth Bruimaire as well as The Communist Manifesto, was also put into creative practice in several of his films such as Dharti ke Lal (1946), Neecha Nagar (1946), and Saat Hindustani (1970), and The Naxalites (1980), to name just a few.

Lucknow’s Bond with K.A. Abbas

Pradeep Kapoor (veteran journalist and ideologue of the Left movement in India, living in Lucknow)

The fantastic response that the book An Evening in Lucknow received in Lucknow in 2011 shows that the city still remembers the book’s author and famous film director late Khwaja Ahmad Abbas. There are many in this city of Nawabs that have fond memories of this eminent writer, filmmaker and journalist. Eighty-two-year old journalist and Urdu writer, Abid Suhail is one of them. He still remembers the famous incident involving Abbas Sahib that took place in August 1967, which came close to causing a serious rupture between writers of Hindi and Urdu languages.

According to Suhail, there was a programme of story narration at Lucknow’s Ravindralaya Auditorium, which was attended by Urdu and Hindi writers from all over the country. When Abbas got his turn to read his story he prefaced his reading with strong remarks about how Urdu was not getting its proper due and why there was a need to declare it a second official language. His statement angered many prominent Hindi writers who were present there and perceived Urdu as the language of Partition. Although there were no television and chat shows, this incident was debated by litterateurs and others all over the country and beyond.

Suhail recalled that the Hindi writer Yashpal, who had been with Sardar Bhagat Singh and other revolutionaries, got up on hearing Abbas’s demand for a greater role for the Urdu language, and announced his decision to boycott the programme, despite being the Chairman of the reception committee. Suo moto he also announced the cancellation of the dinner organized after the programme. Yashpal’s reaction shocked everyone. Sajjad Zahir and poet Firaq Gorakhpuri promptly intervened and persuaded Yashpal to return to the programme. Next day all the prominent writers of Hindi and Urdu, including Firaq Gorakhpuri, Sajjad Zaheer, Abid Suhail, Bhagwati Charan Verma, Amrit Lal Nagar and Yashpal held a meeting and signed what is known as the Hindu-Urdu pact.

Three-time mayor of Lucknow and writer Dr Dauji Gupta, who was also present at the function and was one of the signatories of the pact, remembers that the Urdu writers put their signature in Hindi and Hindi writers in Urdu. Interestingly, mention of the Hindi-Urdu pact that brought the two languages together and also defeated attempts of the imperialists to deepen the divide between the two communities on grounds of language cannot be found be found anywhere today.

I still remember Abbas Sahib’s visit to Lucknow, as he was a very close friend of my late father, Bishan Kapoor, who was bureau chief of the famous Blitz magazine where he wrote his famous column, Last Page, in all the three languages: English, Hindi and Urdu.

I also remember Abbas Sahib’s frequent visits to our residence, where he would meet prominent personalities of this city and interact with them on issues ranging from films to day-to-day life and other important political events. During the period between 1977 and 1980, he made many trips to write his book, 20th March 1977: A Day Like Any Other Day based on the events of the day when Mrs India Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi lost the polls in Rae Bareili and Amethi.

The Naxalites: A Submission to my Dear Ones

By Rahi Masoom Raza

(Translated from Urdu by Syeda Saiyidain Hameed. ‘Alfaz’ first published the article in 1980 and it was republished in 2013 by Sada-e-Urdu, Bhopal.)

The favourite diet of our social and political class is lies. We eat lies, we drink lies, we cover ourselves with lies, we lie down on lies and we export lies and import lies. We smuggle lies like Morarji Desai imported Moshe Dayan.

That is why gentlemen, if we use lies in our films, why should it be surprising? But everyone in our country loves becoming a mirror which will reflect others’ faces, thereby saving him from looking at his own face. The face that is so full of the acne of deceit that it is not worth looking at. That is why if some simpleton places a mirror before us we shatter it and attack the person, ‘How dare he place a mirror before us!’

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas is one of those simpletons; he has just made a film called The Naxalites. The very name scared the Censor Board. So they took out moth-eaten books of law and thumbed through their smelly pages. A letter was then written to K.A. Abbas stating that his film is dangerous for the state. Allah ho Akbar!

The act that Censor Board leafed through was one in which films have been bracketed with gambling, dancing and bar-hopping. This is an act which despite the fact of India’sIndependence, has never been challenged.

A government that brackets films with gambling, dancing and drinking has no business governing a civilized country. But then there is a basic question. Are we really a civilized people if our police barge into our houses and rape women, or in Baghpat they strip a woman and parade her through the market? People instead of beating these perpetrators ask for a ‘judicial enquiry’. The conclusion then is that we are cowards. And cowards are not civilized, because civilization is the hallmark of our individuality.

The Nehruvian Khwaja Ahmad Abbas also encountered this very phenomenon. I have seen The Naxalites; this film is neither dangerous for the country nor a threat to a national integrity. It is also not in favour of ‘Naxalbaris’; it is in fact, critical of them. It blames them for being pro-China and posits that they have been misguided. Frankly, a Nehruvian can have no other point of view. But there are two major ‘falsehoods’ in the film. First, that despite calling them misled, Khwaja Sahib has also observed that this movement was born out of the stinking pool of an unjust social and political order. The second fault is the statement that instead of resolving their economic distress, the government exploits them for daring to raise their voice against the regime.

Khwaja Sahib has fearlessly condemned the government’s exploitation. He has exposed the double face of the ruling class, in the persona of the police officer who after torturing and killing the Naxals sits in his home and plays the sitar, playing it rather well. This officer is symbolic of the rulers who valorize India’s ancient civilization and recite its eulogies, while at the same time inflicting violence on its own people. The ruling classes cannot bear the truth, whether power is in the hands of Morarji Desai, Charan Singh, or Nehru’s daughter, they will not tolerate Abbas’s film. Abbas will have to knock at the portals of the Supreme Court. I am sure that the Supreme Court will clearly see that Abbas’s film, The Naxalites, is not a threat to the country’s security and integrity.

Who are these people who are not ashamed of condemning those who love their country as being the enemies of the state?

I request all intellectuals and students of literature to write to the Minister of Information & Broadcasting about this undemocratic move of the Censor Board. I am convinced that nothing will change but at least conscientious and honest writers and filmmakers will be assured that they are not alone in this fight.

A Man of Many Parts

By Rakhshanda Jalil (writer, critic and literary historian)

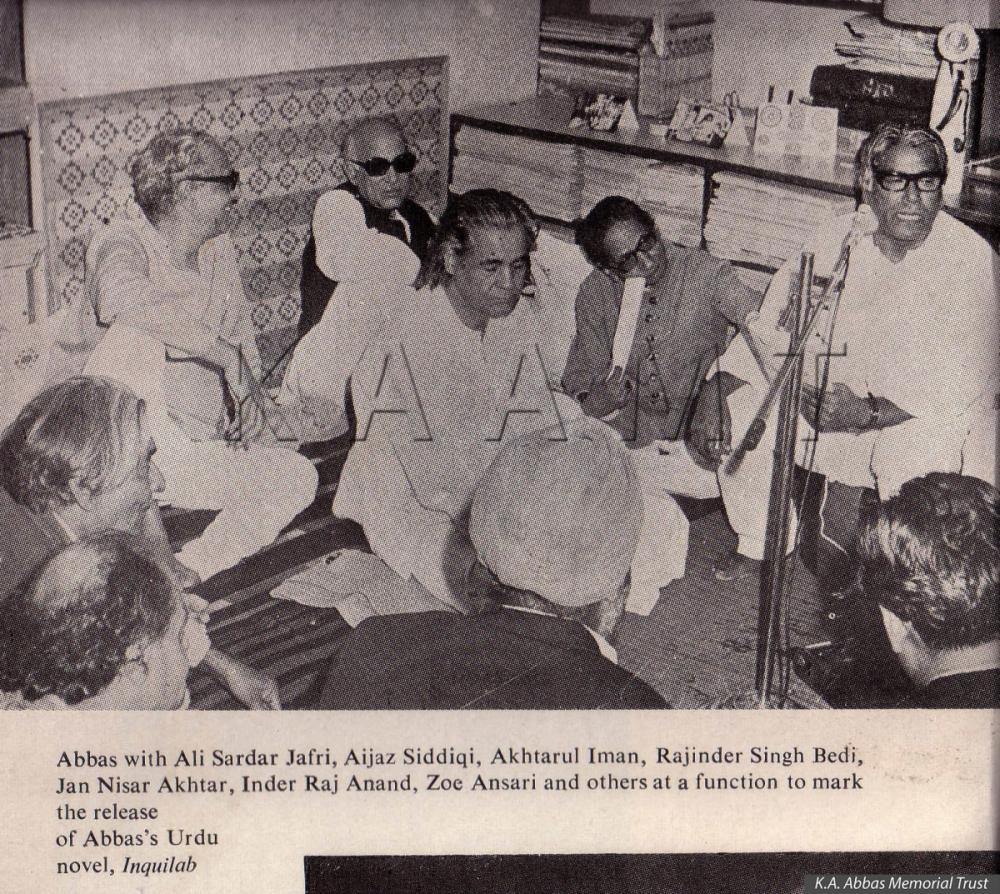

K.A. Abbas was a man of many parts: journalist, film-maker, prose writer in Urdu and English, founder-member of both the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). Today, it is important to revisit his legacy and critically examine all the concerns: gender justice, nationalism, and the need for socially engaged literature.

Unlike the other Urdu progressive writers, Abbas was bilingual; it is often difficult to tell whether he first wrote a particular story in Urdu or in English as he translated his own stories or re-wrote them. In many stories, he blurs the boundaries of fiction and journalism, possibly because he believed that both stem from realism. In his autobiography, I am not an Island, he noted:

…good, imaginative, inspired journalism has always been undistinguishable from realistic, purposeful contemporary literature. There was a special correspondent called Karl Marx whose dispatches to New York Herald Tribune are now part of the scriptures of communism. Steinbeck wrote his Grapes of Wrath as he scoured the United States to investigate the causes of the Great Depression. Hemingway wrote For Whom the Bells Toll as he covered and fought the Spanish Civil War.

An unabashed admirer of Nehru, Abbas embraced the nation-building projects with great enthusiasm. In a preface to an early collection of short stories, he noted:

A few stories may provoke highbrow critics living in isolated ivory towers to utter the dreaded word ‘Propaganda’. But these stories are not about plans, projects and policies of the government. They are about men and women, our contemporaries, the people of a new India, and how their subjective ‘inner life’…in which the positive values of socialism (even where hesitantly and half-heartedly adopted by our government) are playing their own part.

A Piece of the Continent

By Bhaichand Patel (columnist and author)

Once upon a time there were only two news weeklies, Blitz and Current, owned and edited by two feuding Parsis. The Cold War was in full swing, while one (Blitz) was staunchly pro-Soviet; the other (Current) was firmly in the American camp. Paradoxically, Blitz was also a fervent supporter of that despot, the Shah of Iran. Why that was so remains a mystery to this day. The two tabloids were highly opinionated and very loose with facts. Television and a more discerning readership killed them both.

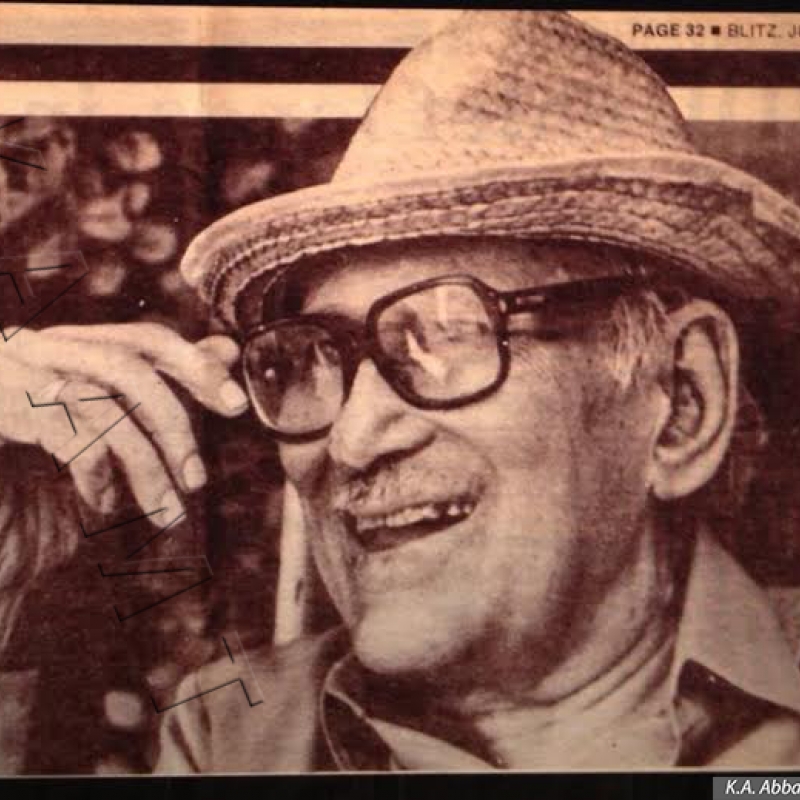

I met Khwaja Ahmad Abbas in 1967 in the corridors of the Blitz’s decrepit office in downtown Bombay. He wrote Last Page, the paper’s popular column that he had brought along with him from Bombay Chronicle after the Chronicle’s closure. The column began in 1935 and continued till Abbas’s death in 1987. It holds the distinction of being the longest-running column in the history of Indian journalism.

My column in Blitz was somewhere in the middle pages, under the grand and self-given title of ‘literary editor’. Though Abbas was much older and quite famous, we became friends. I soon found myself being wined and dined by such Sea Lounge socialists as Russi Karanjia, editor of Blitz, Balraj Sahni, and Rajni Patel, the lawyer who ran Bombay for Indira Gandhi. Once, to my astonishment, I was seated at a dinner table next to Madame Binh, the foreign minister of Ho Chi Minh’s government-in-exile.

Abbas was very versatile. Besides being a journalist, he wrote novels, short stories and film scripts. He was fluent in three languages, Urdu, Hindi and English. He was not so successful as a producer and director of films with the possible exception of Anhonee, starring Nargis and Raj Kapoor.

It was Abbas who first gave Amitabh Bachchan his first role in Saat Hindustani. In a generous foreword to I am Not an Island: An Experiment in Autobiography, the actor fondly recalls when the entire unit of the film unit travelled third class by train to Goa. That was all Abbas, the producer, could afford. Everyone slept on the floor at night in a government guesthouse that had no electricity.

While Abbas' films were not so successful commercially, he had a gift for writing wonderful screenplays that made quantities of money for others. He scripted some of the best Hindi films ever made, including Raj Kapoor’s Awara, Shri 420, Jagte Raho and Bobby. But Raj Kapoor was a notoriously bad paymaster and Abbas survived mainly on the Rs 1,500 he received every month for his columns.

His film career began in 1936 as a part-time publicist for Bombay Talkies, a production house owned by Devika Rani and her husband. Abbas debuted as director 10 years later with Dharti Ke Lal. Another film, Rahi, based on Mulk Raj Anand’s story Two Leaves and a Bud was on the plight of workers on tea plantations. Dev Anand, not yet a star, had the lead role in Rahi and gave Abbas more trouble than any other actor.

Abbas consciously made commercial films and used stars whenever he could afford them and they were willing to work for him. Abbas’s films were progressive, socially relevant films, and his was the most prominent voice of the Left in Indian cinema at that time.