Today when we are almost two decades into the 21st century, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas has become even more relevant than he was in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. He wrote furiously and prolifically for films, newspapers, journals, stories, novels and dramas; his pen flowed in Urdu and English with equal ease. A Hindi typist sat to his right and simultaneously transcribed his writing into Hindi. But somehow, in the interregnum—i.e., the 27 years between his death in 1987 and the revival of his work three years ago in 2014—he was forgotten by both writers and film historians.

What made a motley group of people decide to resurrect Abbas? Perhaps it was destiny. There was no external trigger, which made 2014 suddenly jump at us as a compelling imperative. When we began our work, our tablet was blank, we had nothing except a few books given to me by him as gifts. It was only within the three years that followed his centenary celebrations that one saw the start of what can be called a cult status for Abbas.

The Khwaja Ahmad Abbas Centenary Celebrations Committee was formed; it was headed by the visionary public intellectual and politician Aziz Qureshi. Having carried out half a dozen events over the year, the Committee was dissolved. Thereafter was born the Khwaja Ahmad Abbas Memorial Trust with the objective of using Abbas’s entire corpus as a template for current struggles, most of which are thematic in his writings and films.

This module aims at linking Abbas’s voice with global struggles against intolerance, extremism, religious and linguistic chauvinism, cult worship, corruption, greed, displacement, violence against women and environmental degradation. Abbas stands amidst them, a biblical David confronting the giant Goliath. Or if one were to use popular culture, a perfect analogy would be Abbas Skywalker vs. Darth Vader.

Three short stories have specially been chosen for translation for Sahapedia. Benaras ka Thug, Naya Inteqam and Teen Aurtein. All three are directed at the rotten core of societal norms. Benaras Ka Thug is a Rip Van Winklesque story with an Emperor’s New Clothes theme. An innocent man arrives in Benaras where he lived many centuries ago and shocks the city just by being true to himself. In Naya Inteqam, a sex worker pretends to be dead in order to take her unique revenge on her predator-protectors. And finally in Teen Aurtein, three women walk on a railway line against an oncoming train. Are they three or is it one single woman versus the men who have ravaged them, body and soul ? Abbas’s story storehouse has much more but we decided to whet the appetite by doing this exclusive corner.

One module with a few articles, stories, sketches and film clips cannot do full justice to a man who wrote 74 books in his lifespan of 73 years. Neither can it capture over 100 short stories, the 3000 pages of newspaper columns he wrote for the Blitz and other journals of the time. But it provides a nibble for the palate, which we hope will be hungry to tease out more.

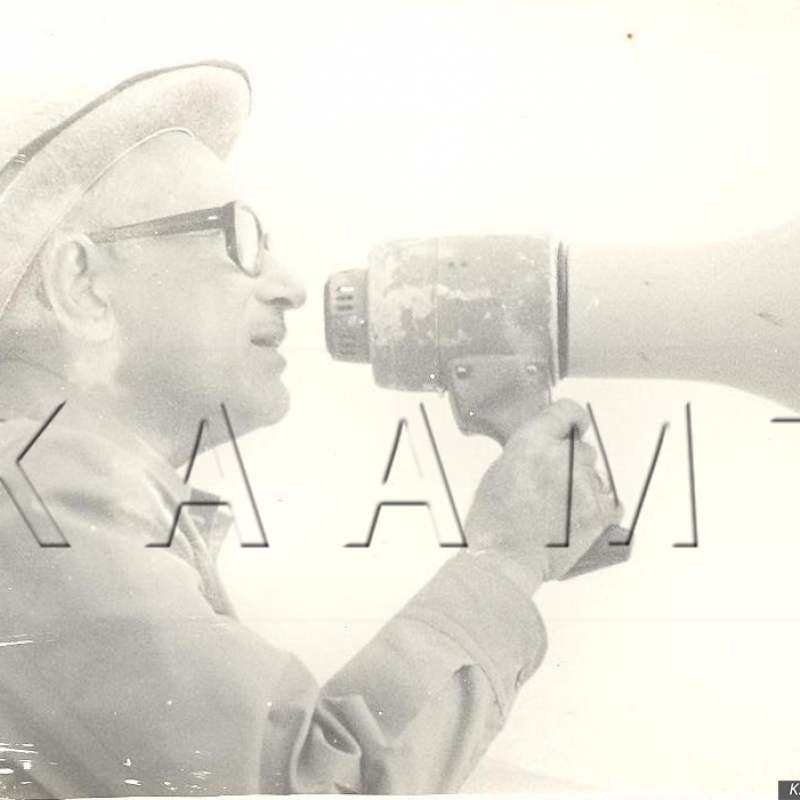

Abbas was the inveterate communicator. He used every medium at his command to transmit his message. His favorite expression was ‘Mujhe kuch kehna hai’ (I want to say something). All his literary activities were subservient to this objective. When he picked up his pen (literally, because he was, at best, a two-finger typist punching at his archaic machine), he wrote effortlessly on whatever struck his fancy, so long as it communicated his objective. His objective was to hold a mirror to society. By exposing the underbelly of polite society he wanted to open eyes and touch hearts. The journalist Amar Kumar (played by Vimal Ahuja) with an ideal and a dream in Bambai Raat Ki Bahon Mein, was Abbas himself refusing to sink into the morass of the rotten samaj (society) by which he was surrounded.

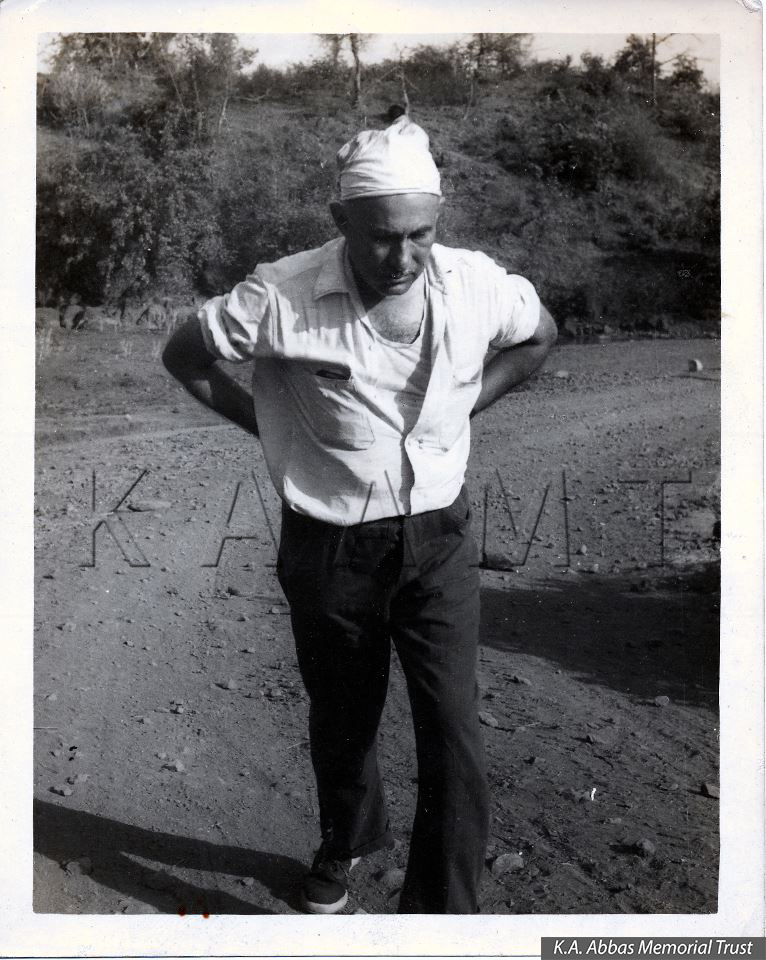

He found hope among the common people. Jawaharlal Nehru, whom he unabashedly loved, once advised him not to take his credo from books or the discourses of others. He advised him to go far into the country’s hinterland and experience the country for himself. This advice is nothing new; wise men and women have given it since the dawn of civilization. Abbas took it to heart. He trudged through the globe on a shoestring budget and picking up nuggets along the way, transformed them into his stories and columns.

A journalist once asked him about the net gain of 22 years of writings on the same subject: ‘What improvements have you affected? Has anything changed on your account? Who is going to bring about the change you talked about?’ Abbas replied that despite his anger and frustration, he has never lost hope in the people and that change will flow from them, sooner or later. In the last article in his book, I Write as I Feel, which is a compendium of his articles for 'Last Page' in the Blitz, he assigns the responsibility for constructing post-Independence India to himself and to the people of India (and Pakistan). He writes:

But the end of one era is also—and always—the beginning of another. The struggle for freedom has ended. But freedom has just begun. The preservation of the newly-won freedom against attacks from within and from without, the enlargement of its scope in terms of social justice and economic betterment of the masses, the need for a cultural renaissance—all these impose fresh responsibilities on all of us. The tasks of reconstruction are as important and as difficult as the struggle to wrest power from unwilling imperialist hands.

This module is dedicated to a ‘hope’ called called Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, a hope against which even death lost out.

Early life and education

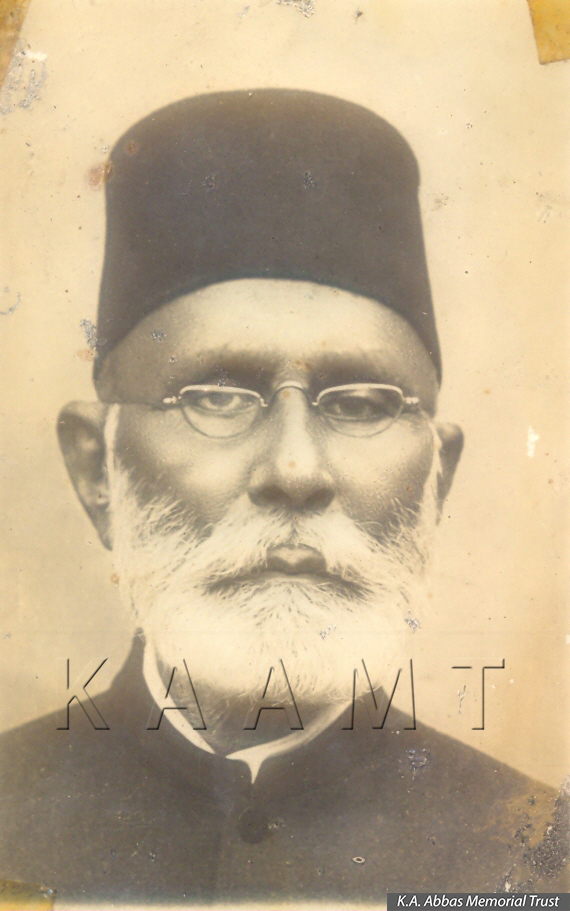

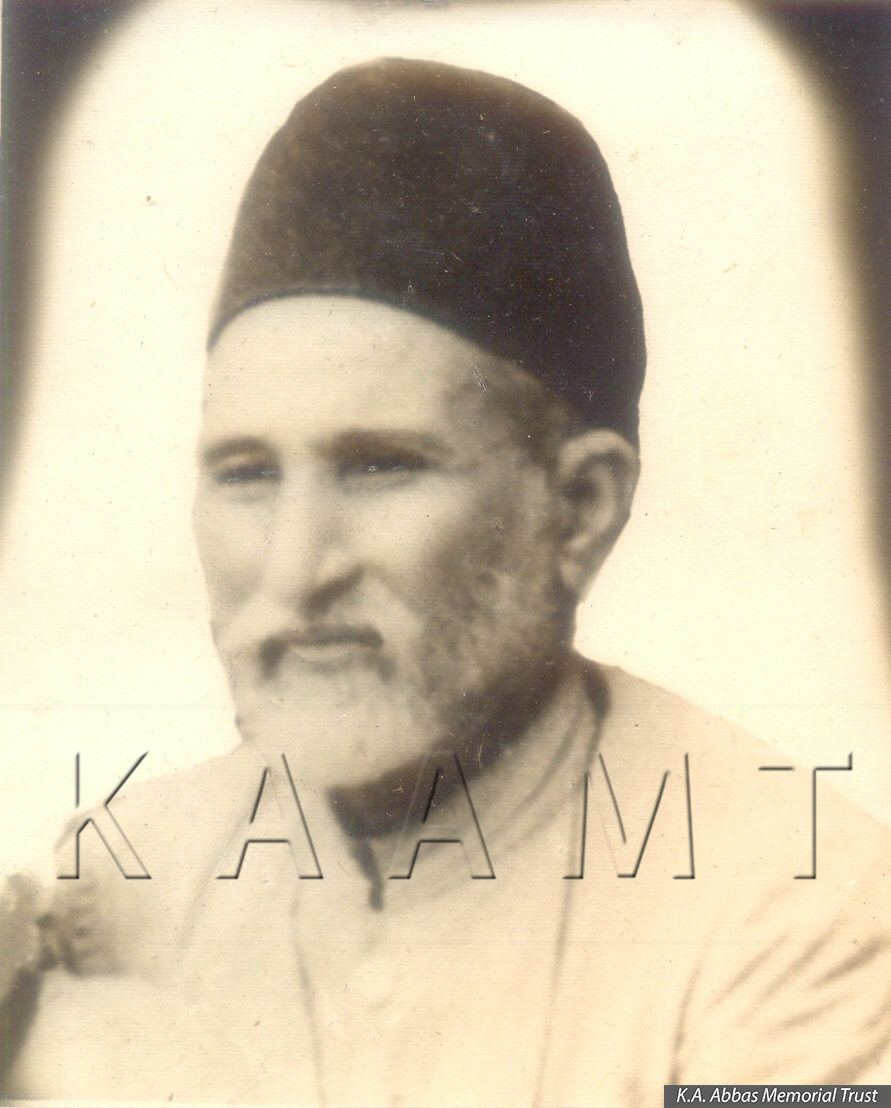

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas was born in Panipat, Haryana in the family of celebrated Urdu poet, social reformer and India’s first feminist poet, Khwaja Altaf Hussain Hali. He was a shagird of Mirza Ghalib. His paternal grandfather Khwaja Ghulam Abbas was a strong votary of the 1857 liberation uprising. There is a popular rumor that he was the first martyr of Panipat, and was blown from the mouth of a cannon. Abbas's father Khwaja Ghulam-us-Sibtain who was among the first graduates from Aligarh Muslim University was a tutor of a prince and a prosperous businessman, who modernized the preparation of Unani medicines. Abbas's mother, Masroora Khatoon, was the daughter of Khwaja Sajjad Husain, son of Hali. He was a passionate believer in Taleem e Niswan (female education) who established the first school for girls in Panipat. Abbas’s early education was at Hali Muslim High School, Panipat, which was also established by his maternal grandfather. Abbas's family tree goes back to Khwaja Ayyub Ansari, the first to host the Prophet of Islam and the band of Muslims when they performed the Hejirat from Makka to Madina in the first year of the Muslim calendar.

Abbas's grandfather, Maulana Altaf Husain Ali

Abbas's father, Khwaja Ghulamus Sibtain

Abbas's mother, Masroora Khatoon

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s first article (at the age of 11) was published in Phool a children’s magazine from Lahore, in 1925. He completed his matriculation at the age of 15. He completed his BA (English literature) in 1933 and LLB in 1935 from Aligarh Muslim University.

Journalism

As a young journalist, Abbas joined the National Call, a Delhi-based paper. Later while studying law at Aligarh Muslim University in 1934, he started Aligarh Opinion, India's first university students' weekly during the pre-Independence period.

Abbas then joined the Bombay Chronicle as Reporter/Sub Editor from 1935 to 1939; as film critic from 1939 to 1940; and as Editor for the Sunday Edition and columnist from 1940 to 1947. While at the Bombay Chronicle (1935–1947), he started a weekly column called Last Page (Azad Qalam in the Hindi and Urdu edition), which he kept alive when he joined the Blitz after the Chronicle’s closure. He continued it until his last days. A collection of these columns was later published as two books, I Write as I Feel (1948) and Bread, Beauty and Revolution (1982).

Films

K.A. Abbas entered films as a part-time publicist for Bombay Talkies in 1936, a production house owned by Himanshu Rai and Devika Rani, to whom he sold his first screenplay Naya Sansar (1941). In 1951, he founded his own production company, which he also named Naya Sansar. It consistently produced socially relevant films includingShehar aur Sapna, Anhonee, Munna, Rahi, and Saat Hindustani. This generation would recognize K.A. Abbas as the one who discovered superstar Amitabh Bachchan.

The first film that Abbas directed was the classic Dharti Ke Lal (Children of the Earth). It was made in 1946 under the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) banner. In 1949, it became the first Indian film to receive widespread distribution in the USSR.

If Anhonee was the first film produced by Abbas’s company Naya Sansar in 1952, it was also the first film in India to feature Nargis in a double role, and Munna (1954) was the first film without songs. Dharti ke Lal preceded Satyajit Ray’s world classic Pather Panchali (1955) by more than a decade. Pardesi (1957) was the first Indian film to be co-produced with a foreign film company (Mosfilms).

As a screenwriter, Abbas is considered a pioneer of Indian parallel or neo-realistic cinema. He wrote scripts for other directors, Neecha Nagar for Chetan Anand (the Palme d’Or winner at the Cannes Film Festival) and Dr Kotnis Ki Amar Kahani for V. Shantaram. He went on to write scripts for most of the prominent Raj Kapoor films such as Awara, Shri 420, Mera Naam Joker, Bobby and the posthumously released film Henna.

Literary Works

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s work spans 74 books, more than 100 short stories and 3000 journalistic pieces. His best-known fictional work remains Inquilab, his historical novel on the freedom movement, which made him a household name, not in Indian, but surprisingly in Russian literature where it appeared as Sen Indie (Son of India). That was 1955 when the book was translated and published in the former Soviet Union with a print run of 90,000. A year later a German edition hit the bookstalls there. Only thereafter did a publisher in Bombay agree to publish it in English, in 1956, after pruning it down by 60 pages, and paid Abbas princely sum of Rs. 750 as royalty which barely covered his typist’s fee. In 1961, his brother in law Munish Narain Saxena rendered the book in Hindi, and Abbas published the Urdu edition himself in 1975 at the age of 61. In 1982 he wrote The World is my Village, which according to him, was the sequel to Inquilab.

Abbas is considered a leading light of the Urdu short story. He wrote his short story Ababeel (The Sparrows) in 1935 at the age of 21. It was included in a West German anthology of the World’s 100 best stories. Like many of his works, it was translated into many Indian and foreign languages including Russian, German, French, Swedish, Arabic, and Chinese.

Abbas’ short stories have been included in anthologies along with stories of Sadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, Ismat Chughtai, Ahmed Nasim Qasmi and Rajinder Singh Bedi, all of whom were his close friends. His short stories like those of his contemporaries were not without their fair share of controversies. Ek Insaan ki Maut caused a hue and cry not only the first time it was published, but every time that it appeared in magazines. It was also published under the title Sardarji, which had the Sikhs up in arms and even led to Abbas being summoned by the Allahabad High Court. Khushwant Singh later translated it under the new title The Death of Shaikh Burhanuddin. Khushwant Singh wrote that no book of ‘Punjabi’ stories would be complete without this highly controversial story. Ironically, the story was written entirely in Urdu!

Abbas interviewed several renowned personalities in literary and non-literary fields, including the Russian Prime Minister Nikita Khrushchev, American President Theodore Roosevelt, Charlie Chaplin, Mao Tse-tung and Yuri Gagarin. He was the first biographer of Indira Gandhi and in fact wrote a bio-trilogy on her: The Return of the Red Rose (1966), That Woman: Her Seven Years in Power (1973) and Indira Gandhi: The Last Post (1975). He wrote biographies of Nikita Khrushchev and Yuri Gagarin. His autobiography, I am not an Island as well as other novels written by him have been translated in a large number of Indian and European languages and command a wide readership all over the world.

Association with Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) and Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA)

Abbas’ early career dates back to the Progressive culture and tradition that prevailed in India during the 1930s, '40s and '50s. Like many of his contemporaries he was one of the leading exponents of the All India Progressive Writers’ Association (AIPWA) established in 1936, and its allied theatre organization the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) established in 1943. As a stalwart of the PWA and IPTA, it was no surprise that the first film that Abbas directed was the classic Dharti Ke Lal (Children of the Earth). Even the cast of the film consisted mainly of actors from the IPTA. It was also the first film produced by IPTA and remains one of the most important Hindi films of the century. Based on an IPTA play, it was the first realistic film on rural indebtedness and dispossessed peasantry shown in the context of the Bengal famine. The film marked the screen debut of Zohra Sehgal and also give actor Balraj Sahni his first important screen role.

Abbas also wrote for IPTA a half-hour one-act fantasy play, Yeh Amrit Hai (Invitation to Immortality) in which a scientist who discovers the elixir of life is approached by representatives of different sections of society (e.g., an imperialist, a capitalist, a decadent poet, a society butterfly, a man of religion, and a dictator who is a cross between Hitler and Mussolini) but he gives it only to a worker who would not take it, for he says he is already immortal. The play was a big success and Abbas was therefore pressurized to write a full-length play. That is how he came to write his first full-length play Zubaidah. Abbas first read it out at the rehearsal room of IPTA in the little basement hall of the Deodhar School of Music in Bombay. Among the members who heard the play were Balraj Sahni (who later directed the play for IPTA in 1943), Damyanti Sahni, Chetan Anand and Dev Anand. Abbas himself offered to play the old Meer Saheb, the arch reactionary of the play.

Cover page of Zubaidah

The Last Page

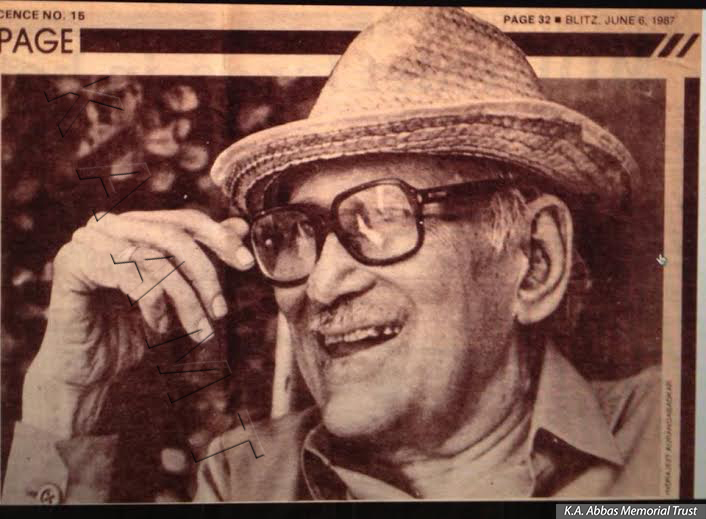

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas breathed his last on June 1, 1987 after a career spanning over half a century. He emerged on the Indian and global scene as a communicator par excellence. He lived a life consistent with his high values and ideals and used his genius trying to reach the masses, more or less uneducated, audience of millions. He worked tirelessly, and as he grew older, he became an institution.

Abbas's health began to fail in the 60s, when he suffered his first heart attack. His eyes gave trouble; but the worst was an accident, which happened at an airport. A luggage trolley ran over his foot. As he doubled up with pain and tipped over, the woman behind the trolley said sorry and disappeared. That for Abbas was beginning of the end. After immediate hospitalization he was in and out of the hospital. He attended his very last meeting, the Producer’s Guild Meeting by sneaking out of the hospital on a makeshift stretcher carried by his friends. This was a few weeks before his death. Everyone was amazed to see him coming out of a taxi in his hospital kurta pyjama. Abbas had been an active member and one time President of the Guild. Until a few days before his death in June 1987 he was shooting for his film Ek Aadmi (One Man) which was autobiographical, a chronicle of his own life. It was released posthumously in 1988. Since all doors for financing were closed he wrote with his now semi-paralyzed hand a letter to family and close friends asking for small contributions (a first instance of crowdfunding) which he promised to repay, to keep up the shooting schedule.

Abbas seldom compromised on his ideals, social and political; these became his lifelong crusade. He liked to take his battles to the bitter end. 'My motivation (despite commercial failure of films) remains the same. To communicate my thoughts to as large a public as possible,' he told Suresh Kohli in his last interview from his sick bed, when Ek Aadmi was nearing completion; the interview was published posthumously in Filmfare (June 16–30, 1987).

A few weeks before his death, Abbas sent a leave application to the Editor-Founder of the Blitz, R.K. Karanjia requesting few weeks leave. Here was a man who wrote his weekly column for 46 years without a break and what does he do under the shadow of death? He writes a leave application letter!

Quotes

I don’t expect to be first rate in anything—I was content to be a second rater in all these films, novel, short story—I change the media to give myself rest. When I tire of one I turn to the other.

——Interview with V.P. Sathe for All India Radio

Thus we step across the bloody threshold of history. And we shall be better able to find our way in the future if we have a clearer perspective of the past. For the past lives in the present and the present in the future. There is neither end nor beginning.

——From I Write as I Feel (full article here)

Journalists are notorious for dashing off their stuff at the 11th hour (sending it to the press, ‘hot’ from the typewriter) even when they write a weekly column. As my editor will endorse, with justifiable indignation, The Last Page, week after week, has reached his desk not at the 11th hour but on the tick of the 59th minute of the 12th hour. I am not particularly ashamed on this account, though I am conscious of the trouble I caused to the editor and the printers. For in a world and at a time when the national and international situation is liable to fluctuate every hour, one cannot risk going to the press too early with one’s column.’

——From I Write as I Feel

Some people say I am mulish in trying out themes of social realism, without compromise. 'Give the people what they want,' they advise. But I believe in doing what satisfies not only my personal ego but my social conscience. I have no martyr complex. I have enjoyed making each one of my films.

——K.A. Abbas (personal correspondence)

I have seen the Taj and Ajanta as also the Acropolis and the Parthenon; I have trekked up to the flower-strewn meadow of Khillanmarg in Kashmir, and taken a lift to the top of the Empire State Building to look at the utterly fantastic panorama of New York by night.

I have seen the serene face of the Buddha at Sarnath and the sad smile of Mona Lisa; I have suffered with Christ and laughed at Charlie Chaplin’s sadly comic tramp. Together with other fellow students I have cried with anguish when the news came that Bhagat Singh had been hanged; and I cried with joy as I danced, with a hundred thousand others, on the streets of Bombay on the day of freedom – 15 August 1947.

All this I have witnessed, observed, experienced, felt, all this is within me, a part of me, and I am a part of all that I have observed, experienced, felt! The world has made me and I have made the world (at least two thousand millionth part of it), I am involved in humanity even as humanity is involved in me, as the seed is born of the tree, and the tree is the offspring of the seed.

——From I am not an Island