My mother travelled all the way from Panipat to Bombay (now Mumbai) in the mid-1940s to receive proper medical attention in the care of a loving sister-in-law, Mujtabi Khatoon (Mujji). Here in Bombay in a small flat in a building called Samandar Tarang I was born as yet another K.A.A. because Khwaja Ahmad Abbas baptized me as Anwar, his favourite name and the hero of most of his films and books. Next door lived Shahid Latif and Ismat Chughtai with their only child, Seema. Coincidentally, Seema joined Air India as a flight attendant and some years later, I joined as an Assistant Station Superintendent.

Mujtabi Khatoon (Mujji)

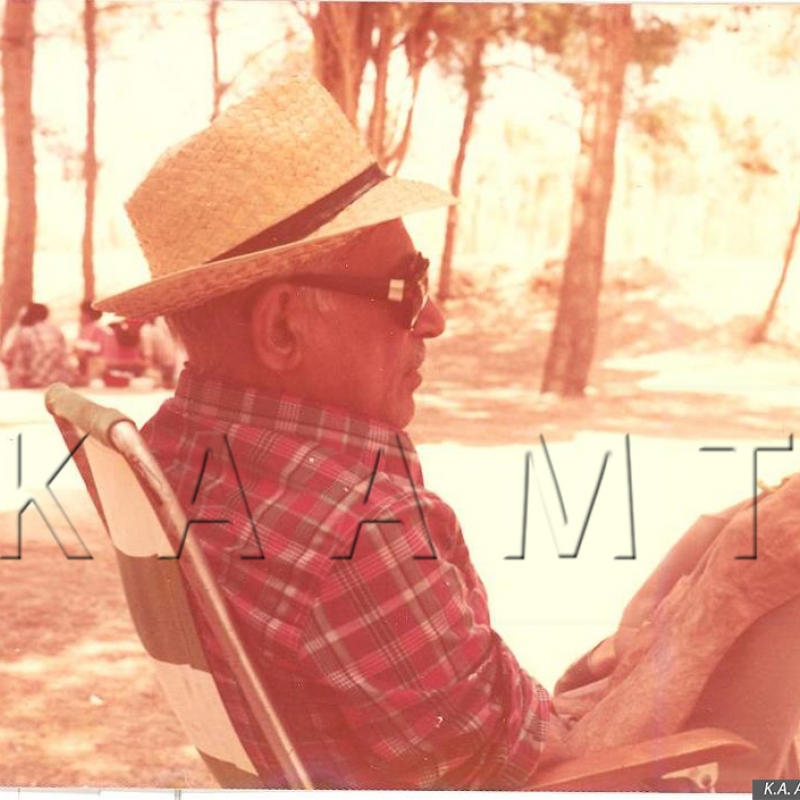

Along with my two sisters, my cousins and Seema, we would play on the beach with Mamujaan (K.A.A.) and build castles in the sand. But during high tide, our castles would be destroyed by waves which would lash even the walls of the building. We would be dismayed by the broken castles but enjoyed the splashing water from Arabian Sea.

This is how Captain Wasiq Hasan of the British Indian Navy and (later Pakistan Navy) describes K.A.A.’s home:

Whenever any ship docked at Ballard Pier, I would disembark and hail a taxi for Shivaji Park, sometimes arriving at the house well after midnight. To my surprise I found several men sprawled on the floor under the dining table. Many of them, including Balraj Sahni, Dev Anand and Prem Dhawan were then unknown persons, but later became familiar to the visitors. Stealthily I would walk over the bodies to move towards the bedroom when Mamoo Bachhoo’s voice would softly say, 'Mujji is sleeping inside and Sneh Lata Pradhan (a popular actor of her times) is sharing her bedroom. Don’t disturb them, lie down where you can find some space.'

The World is my Village is not just the extension of K.A.A.’s first novel Inquilab (1958) but also a philosophy of his life. It was not just the group of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) but people from all over the world who K.A.A. met during his travels and his professional work as a journalist, writer and filmmaker, whom K.A.A. made friends with.

This is one of the differences that I had with K.A.A. Many years ago, my wife and I locked his almirah (wardrobe) of clothes, since many of his friends and unit members would walk away with his shirts, sweaters and scarves. K.A.A. was livid and said, 'Whatever I own belongs to everyone else. You are welcome to my items as well.' Many of his books were removed from his personal library and he would smile away and say, 'Theft of books is no theft.' Years later when he wanted some of the 73 books he had written, he wrote an appeal to friends and relatives to send the books so that he might photocopy them and return them in good time. But except for three of four books, he did not receive them back.

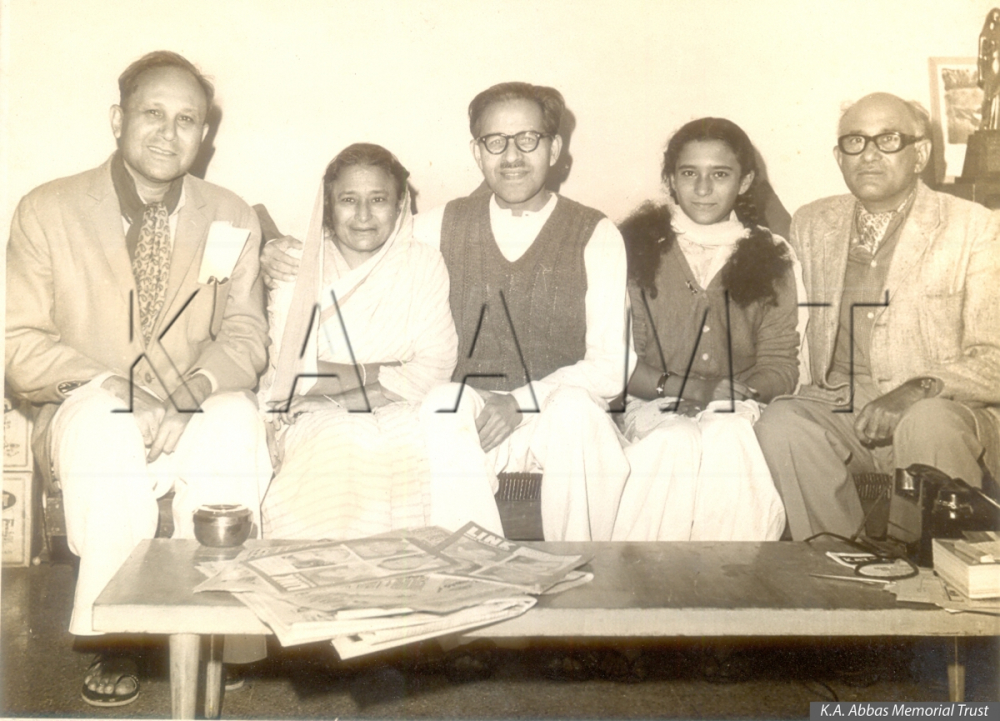

Azhar Abbas, Ahmed Fatima, K.G. Saiyidain, Meena Abbas and K.A. Abbas

With his cousin Azhar Abbas

K.A.A. always believed in living in rented houses and had no interest in private property. In 1952, when he launched his first production, Anhonee, he was living with his cousins Khwaja Ghulamus Saiyidain and Khwaja Azhar Abbas. Interestingly, whenever the doorbell rang my cousin Syeda and I would rush to the door.

'I want to meet Mr. Abbas.'

'Which one?,' Syeda would ask mischievously.

'I want to see Mr. K.A. Abbas.'

I would ask, 'Which K. A. Abbas, there are two of them?'

Sometimes the visitor would turn back and leave.

While Abbas was engaged in shooting in Chembur, he would spend his evenings playing hockey in the Oval along with his unit members. Us youngsters would also join in wearing the same uniform that he had provided to his Naya Sansar team. 'Whenever I am close to the goal mouth,' Ahmed Abbas would mourn, 'These rascals put their little hockey sticks in front and deny me goal scoring.'

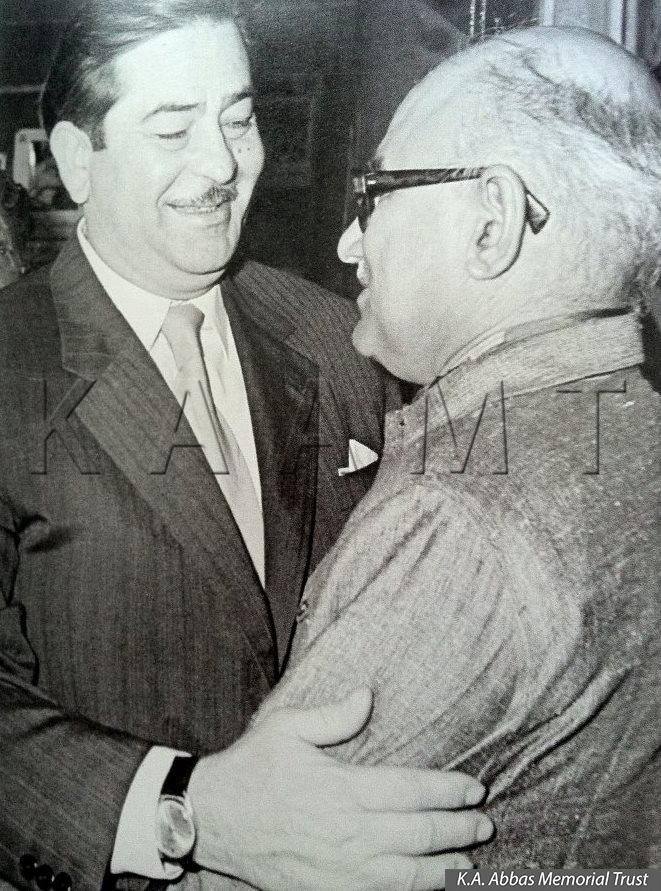

His resistance to private property was irksome to me. We lived in the two-bedroom house at Philomena Apartments on what is now known as Khwaja Ahmad Abbas Marg. The landlord in typical Catholic generosity offered K.A.A. the upper storey of one of the larger and newly-built apartments on ownership basis, if he would release the ground floor rented flat, where, ostensibly, he wanted to build a commercial establishment. But Abbas was no taker of this proposal. At one time I booked a flat with my company’s loan, in the neighbouring building. He persuaded me to release the booking saying, 'Who does my flat belong to? You, of course.' It may be remembered that we occupied the two bedrooms while the humble K.A.A. slept in the drawing room, often sharing it with some of his unit members. This is the room where Raj Kapoor in a drunken state expressed his undying love and devotion to Abbas and the house staff peeping from underneath the dining table watched the ‘live show’.

With Raj Kapoor

As for travelling, K.A.A. never had a problem. He would often buy his air ticket in the erstwhile Soviet Union where his earnings on books and films were blocked. This way he would engage in his own version of money laundering. While K.A.A. could buy a brand new Hudson car (a fuel guzzler) or receive an Ambassador car as a gift from Raj Kapoor, through his father Prithviraj, for the stupendous success of Bobby, he was quite happy to use public transport—sitting on the upper deck of a BEST bus, or hanging from an overcrowded second-class compartment in the local train, precariously holding the bar. Whenever he used a taxi he would make sure that he had enough tasks in the city to justify the high expense. Once while walking down a line of taxis in front of Sheraton Hotel he was asked by a taxi driver, ‘Sahib, where do you want to go?’ He replied, ‘I want to go to Juhu, but not in your taxi.’ The taxi driver would beg him to sit in his taxi so that he could get a lamba bhada (long-distance fare). But K.A.A. would not be moved.

With Prithviraj Kapoor

On one occasion, as he was waiting for a BEST bus near his house, Dev Anand’s limousine stopped in front and offered him a lift. ‘No, thank you,’ said Abbas, ‘My bus will take me where I want to go.’

Once he took a taxi from Juhu to Flora Fountain when he was called by R.K. Karanjia to write what was meant to be an obituary for Nehru, who was fighting for his life at Teen Murti House in New Delhi. When Karanjia pressed K.A.A. to give a headline for the obituary, he titled it, ‘Nehru Lives’.

Abbas’ younger sister lived in Karachi. Since he had written a few articles against the Two-Nation Theory, K.A.A. was blacklisted and not permitted to enter Pakistan, but this did not deter him from visiting his sister and family periodically. The stratagem was to buy a first-class ticket from Moscow to Bombay via Karachi and make the connection that would allow him at least 48 hours on Pakistani soil. He would be taken to the airport hotel and confined to his room. He would call all his well-connected friends and relatives and in the wink of an eye be at his sister’s house laughing and joking with his old friends from Aligarh.

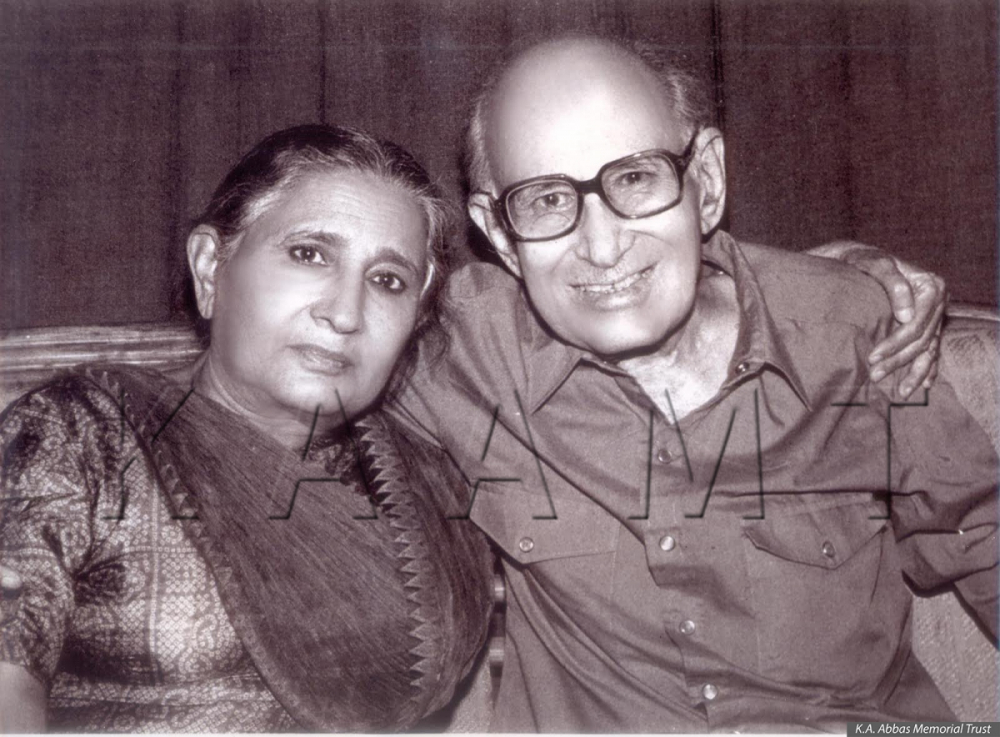

Abbas with his sisters

In 1970, he joined his nephew’s barat [the bridegroom’s procession] to travel by train from Bombay to Karachi via Delhi and Lahore. But to his dismay, he learnt that the visas of the two K.A.A.s had been turned down: the senior one for diplomatic and political reasons and the junior one, the bridegroom, for not having an endorsement for Pakistan.

Abbas with his sister Ahmed Fatima

With younger sister Akhtar Fatima

The junior went to the Pakistan High Commission and argued that he had an endorsement ‘for all countries of the world’ and presumed that Pakistan was part of the world. Having lived a long time with K.A.A., I had modeled my life and thoughts on his patterns. K.A.A. returned to Bombay, but through the efforts of his friends in the Ministry of External Affairs, T.N. Kaul and Keval Singh, he arrived in Karachi a day before the nikah ceremony.

But he would not be cowed down by diplomatic postures. At a press conference, when he was asked whether there was a state in India with Urdu as its first language, he replied ‘Of course, Jammu and Kashmir.‘ The next day the newspaper headlines shouted out ‘Abbas calls Jammu and Kashmir a part of India. He has ostensibly come for his nephew’s marriage, but we suspect deeper motives to his visit.’ K.A.A. received threatening looks from all as he made way to the aircraft and I made every effort to keep him away from any attack against him.

In the mid-1970s, when we were in Libya, K.A.A. dropped by Tripoli on his way to Bombay. The first thing he asked was why Libya asked for the passport to be translated into Arabic. He then commented on the cowshed-like appearance of the airport terminal and the total chaos in the customer’s lounge. I reassured him that the translation was required because the passport was in English. If it were in Hindi, Libyans would have no objection.

I also pointed out to him the Libyan Power Minister, holding two suitcases in two hands and his passport between his teeth, rushing from one customs officer to another to clear his baggage. There was no protocol for him when he returned home after signing the Rs 100–crore Project Misrata with the Government of India. On the other hand K.A.A. had two persons to assist him: my assistant Zafar Akbar and myself. Later I pointed out Colonel Qadafi, driving his car on the road, taking his son to an Indian doctor in the hospital. I also told him of the highly subsidized prices of rice, sugar and other edible oils for the benefit of the common man. So moved was K.A.A. that on his return to Bombay he devoted three of his 'Last Page' columns to his visit to Libya and the People’s Revolution being carried out there.

K.A.A. was always my guardian angel. After my education at Elphinstone, I was given a job as a junior sub-editor and reported with Blitz. Here is where I wrote my breakhthrough article, ‘Blossoms in the Storm’. Some years later when my elder sister, the late Nargis, went to our Nagpada home for her research, the Director asked her to convey his thanks to Mr Abbas. She told him that he was her uncle. ‘But,’ said the Director, ‘he was a young man and perhaps younger than you.’ It then dawned on her that he was referring to her younger brother.

K.A.A. helped me find a slot in Air India through his friend R.K. Karanjia. Later at Balmer Lawrie, as Chief of Tourism, I managed to book a large incoming group of American dermatologists to visit India as our clients. This was big business but there was a catch. They placed the condition that the tour agents arrange a meeting for them with the President of the Red Cross Society of India. To my good fortune K.A.A. visited Delhi to have his new book launched by the Vice President of India. I went along with him to Akbar Road, when he visited the Vice President and here I requested him to host the American dermatologists. He agreed and I bagged the group of tourists.

After Mrs. Indira Gandhi’s death K.A.A. wrote, ‘The Last Post’, for which he wanted to interview the then Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi. In the PM’s office Rajiv Gandhi had Mani Shankar Aiyar by his side and K.A.A. had me with him for support. The interview went off well enough but at the end K.A.A. asked the PM two thorny questions: 1. Did your mother have dictatorial tendencies?, and 2. Do you think super computers are more important than milk for children? The PM who walked up to the door to receive K.A.A. earlier, sat in stony silence. When we left, I asked K.A.A, ‘Why did you ask these two questions?’. ‘To test the mettle of the young man,’ he replied. ‘But this interview could get you places, like a handsome honorarium, a chair in the media university or an advisory post.’ ‘What can anyone give me at this age except death?’ was his reply.

Once in Delhi, K.A.A fell ill and we called a neighbourhood doctor to attend to him. ‘What did you do before retirement?’ asked the doctor. ‘Doctor, I am in the profession where only God can retire me.’

The man who dedicated a book, Till We Reach the Stars (1961), to me when I was still in college, looked forlorn holding the railings of the balcony as the taxi carrying my wife, daughter and me left for the airport. He probably wondered if he would ever see us again. But his sister and I visited him while he was ailing to make his living arrangements comfortable.

I did not ever see K.A.A. cry. He may have done so at the demise of his beloved wife and his father, but I did not see it. Once, while I was reading to him newspaper reports of Sunil Dutt’s Pada Yatra [literally means ‘pilgrimage on foot’, often undertaken. as in this case, to make a political statement] from Bombay to Amritsar, to pray at the Golden Temple and ask for forgiveness for the massacre of Sikhs. Abbas cried. It showed his deep love for secularism and for the saint of India’s freedom struggle: Gandhiji. Sunil Dutt walking with the aid of a stick and with his head covered must have brought back memories of the Salt March undertaken by Mahatma Gandhi. I saw tears rolling down his wrinkled face.

K.A.A. finally ‘resigned’ on June 1, 1987, leaving behind a large number of his ‘family members’, whom he always cherished and belonged to as much as his close blood relatives.