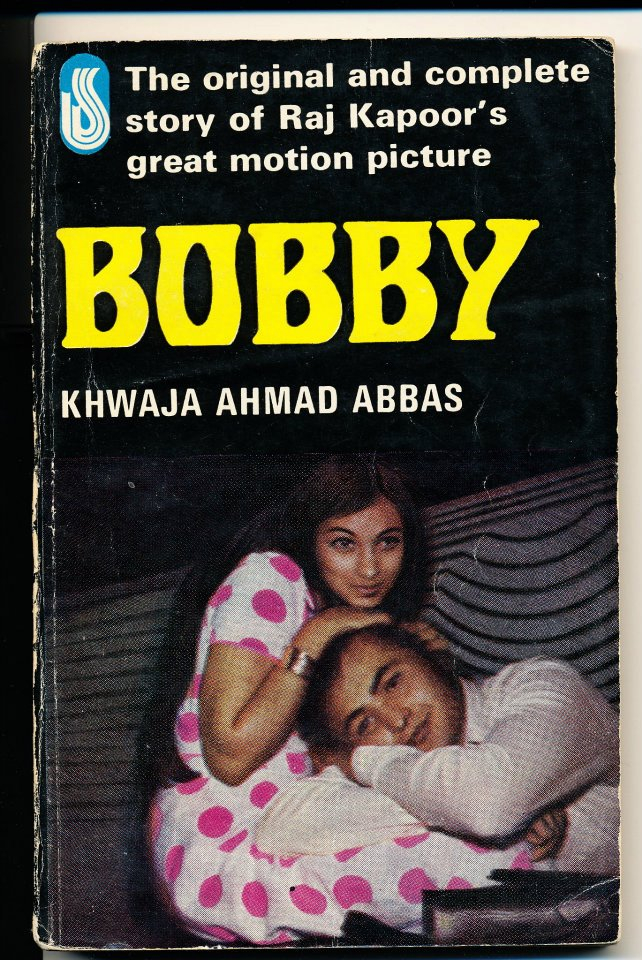

Scriptwriter, director, writer, journalist K.A. Abbas’ contribution to Hindi cinema is unique in several ways. Firstly, he negotiated what I would like to call a ‘bipolar order’ (not to be confused with bipolar disorder, which is a medical term). By this I mean that he found a way of articulating his own, very committed, political views in his own kind of narratives through films and contributing scripts to the Bombay film industry (at a time when it was emerging as the dominant industry in India) that became ur-narratives of a sort and set the paradigms for those narratives for decades to come. Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (Vagabond, 1951) is one such film and Bobby (1973), which Abbas co-wrote is another, which provided the paradigm for young love and teen-romances across economic and social divides.

Awaara was a monumental work in terms of scripting, for it showed, among many things, the nature of transitions (from the smaller town to the big city; from wealth to impoverishment; from a huge bungalow to the slums; from the town’s elite to the underbelly of the city; from being a dacoit to being a gangster), the trauma they induce and the fortitude with which they are borne. The central character in Awaara can be said to be the mother, played by Leela Chitnis, who is given an allegorical dimension in the film, encapsulated in the song ‘Zulm sahe bhaari janak dulari/Pativarta Sita mayi ko tune diya vanvas/Kyon na phata dharti ka kaleja/ Kyon na phata aakash? (Janak’s daughter, Mother Sita, had to bear extreme injustice; when you exiled her to the forest, despite her devotion to her husband, why did the earth’s chest not tear apart? Why did the sky not burst?).

The central argument of the film that Abbas underlines is that the determining factors in an individual’s life are circumstances and the environment and not his/her genes. This debate was important in the discussion around what makes a ‘criminal’, especially for those who lie outside the orbit of institution-building in the newly-independent Nehruvian India. In times of transition, it is the criminal, the marginal, who tests the discourses of nation and nationality, law and lawlessness and points to the tears in the arguments of inclusivity. It is to Abbas’ credit that he was able to think up a popular narrative to embody all these transitions and debates of post-Independent India, and create a polyphony of voices: the mother, the fanatical law-abiding father, the son and Jagga, the dacoit-turned-gangster.

I call this the ur-narrative, because along with Mother India it forms the framework for Salim-Javed’s scripts of another transition time in India, the 1970s. The son, who loses his father (the word of law), literally or metaphorically and gravitates towards a surrogate father (who is a criminal) forms the core of Salim-Javed scripts from Deewar (Wall/1975), to Trishul (Spear/1978), to Shakti (Strength/1982), which embodied the rebelliousness of the ‘angry young man’. The ur-dialogue for the ‘fatherless’ son can be this one by Abbas, when Raj (played by Raj Kapoor) tells his father, Judge Raghunath (played by Prithviraj Kapoor) who offers him money to leave his adopted daughter Rita (played by Nargis) alone: ‘Aaj tak mujhe laga tha ki mujhse neecha koi nahi gir sakta, par aap to mere bhi baap nikle’ (You turned out to be my father in lowliness). The weight of this dialogue cannot be taken lightly: it carries the seed of Abbas’ critique of Nehruvian India.

If the institutions being built shunned inclusiveness and insisted on genetic privilege over genuine democracy for all, if they lacked compassion and sensitivity, as is represented by Judge Raghunath’s character, then they had to be rejected. We see this in the courtroom sequence in Awaara where Raj speaks out against his father, the law and the elite who do not take cognisance of the parallel ‘society of the gutter’. This is the moment of the subaltern[1] not just speaking, but speaking out against injustice.

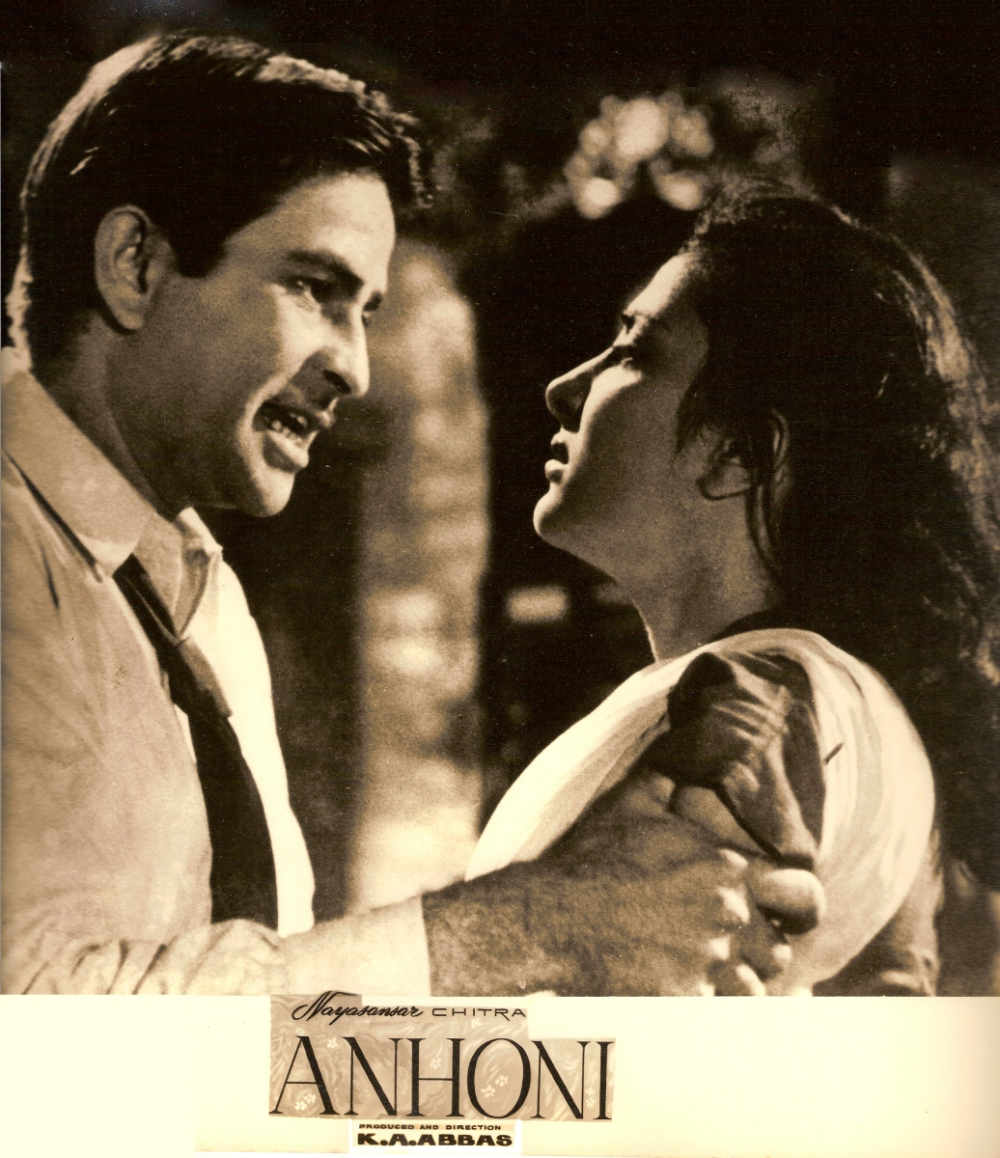

If this popular scripting of social issues was one part of the bipolar order, the second was the examination of this through a narrative that he himself would direct, under the banner of his company, Naya Sansar (established in 1951) such as Anhonee (The Extraordinary), which was released on the heels of Awaara in 1952. This is an amazing film because it subverts many of the paradigms Abbas had set up in Awaara with regard to the ‘genes vs. environment’ debate. Nargis is in a double role and it is of importance that Abbas explores this theme through a female character, where the notion of ‘sacred’ and ‘profane’ space has immense significance.

Roop has grown up under her father’s loving gaze and is the sole heir to his immense wealth. Raj Kapoor is a struggling lawyer and a tenant in one of the houses she owns. They fall in love. One day he gets a new client Mohini, who is the spitting image of Roop. Mohini is not shy of proclaiming that she has arrived in town from the red-light area of Calcutta and smokes, speaks and behaves with abandon and states ‘Hum bhi to samaj sewa karte hain’ (We also serve society). The girls and Raj realize that the two are, in fact, sisters, and that Mohini is the daughter by a woman the father used to visit in the red-light area. Mohini asks Raj to fight her case to get her share of the father’s property that is due to her.

The narrative thus far, would have sufficed as grist for a popular film. Abbas, however, pushes the envelope further, raising questions that would not set the registers ringing at the box-office. When Roop offers to share half of the property with her sister, Mohini asks if she will also give up Raj, because she too is in love with him. Abbas then pushes the narrative to another extreme, breaking the boundaries of the ‘sacred’ and the ‘profane’. The ‘acceptance’ of the ‘other’ by Roop and the sharing of property fall within the discourse of ‘equality’ and ‘justice’ as a way of acknowledging that there are differing worlds and people who inhabit these out of necessity, and that space has to be made for them.

What Abbas does is unique because he introduces a new twist to the story, that the two children had, in fact, been exchanged by the ‘other’ woman as vengeance for being rejected by the father. So it is the ‘legitimate’ child who has actually grown up in the profane space and the illegitimate child who has grown up in the sacred space of the home. Mohini’s demand, therefore, of Roop giving up something as intangible as ‘love’ punctures all the stable identities held so far. Roop’s injunction to her sister ‘Agar pitaji ke naam ka hakdaar banna chahti ho to uske kaabil bhi banna hoga’ (If you want to be a claimant to our father’s name, then you will have to make yourself worthy of it) gets injected with irony, because it is she who is the illegitimate child. The question that Mohini poses Roop, thus cannot be easily answered: ‘Had I had your upbringing and you mine, would he still have loved you and hated me?’ The woman, who finally kills herself in front of the father’s portrait, knowing she cannot win in this love triangle, and understanding that she can never gain legitimacy, is actually the legitimate daughter. The woman, who wins all in the end, is the illegitimate one, who has the finely-wrought demeanour of ‘high’ society.

All opposing binaries are thus scuttled by Abbas in this narrative. Raj Kapoor unwittingly says, ‘I cannot love day and night together’ and calls Roop ‘devi’ and Mohini ‘shaitan’, but at the end of the film, Abbas shows that day/night, devi/shaitan (goddess/Satanic villain) are all fluid and interchangeable categories. Subsequent double role films never went this far: Ram aur Shyam (Ram and Shyam/1967), or even those with women in double roles such as Sharmilee (The Shy Girl/1971), Seeta aur Geeta, (Seeta and Geeta/1972), Chaalbaaz (The Streetsmart One/1989) played with the inversion of spaces and characters (country vs. city; street–smart vs. docile and homebound), were oriented towards humour and not tragedy as Anhonee was, and never made love the object of the split (each twin found his/her own love-interest, by giving up space to the other double). When there was only one love-interest as in Sharmilee, the narrative was built around the ‘good sister’ and the ‘bad sister’. Abbas, truly modern, kept away from the pitfalls of such easy binaries.

Diverse Genres

K.A. Abbas started working in the film industry in the late 1940s and ’50s, a period that Iqbal Masood called the ‘Golden Age of Indian Cinema’. What made this age golden was that the narratives of this period had not yet been poured into fixed moulds; there was a lot of experimentation within the popular format. The movements launched by the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) in 1936 and the Indian Peoples’ Theatre Association (IPTA) in 1943 were some of the most significant mass cultural movements in 20th-century India. Their effects were felt not only in the fields of literature and theatre, but also in the Bombay cinema of the time. They also exerted an influence on the Indian New Wave Cinema.

The ruling themes of the ideological horizon of the time were three: Gandhian ideals of non-violence, social equality of castes and secularism; Nehruvianism defined above all by institution-building; and Marxism, with its focus on the problems of social justice to the working class and the poor peasantry, and the need for unity and collective action. These three themes were themselves not monolithic, with clear-cut distinctions, but created a specific ideological horizon, in which the underprivileged, the dispossessed, the displaced and the marginal were dominant.

The Nehruvian vision shaped the ideological horizon of the '50s, and given the presence of a Marxist line in Nehru’s thinking, its coming together with the IPTA line did make the ideological scales weigh in favour of a Left orientation in the narratives of the time. Directors, scriptwriters, song-writers, composers, actors all left their progressive imprints in the films produced during those times. Among the well-known actors who had an allegiance to the IPTA were Balraj Sahni, A.K. Hangal and Utpal Dutt; well-known music directors included Anil Biswas, Salil Choudhury, Hemant Kumar and Ravi Shankar; song writers Sahir Ludhianvi, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Prem Dhawan, Shailendra, Kaifi Azmi were associated with the PWA and IPTA; scriptwriters K.A. Abbas (also a director) and V.P. Sathe were IPTA members; directors Bimal Roy, Shombhu Mitra, Mohan Sehgal were closely involved with the IPTA, as were the dance directors Uday Shankar and Prem Dhawan (who choreographed songs in Do Bigha Zameen (Two Thirds of an Acre of Land/1953) and Naya Daur (New Age/1957).

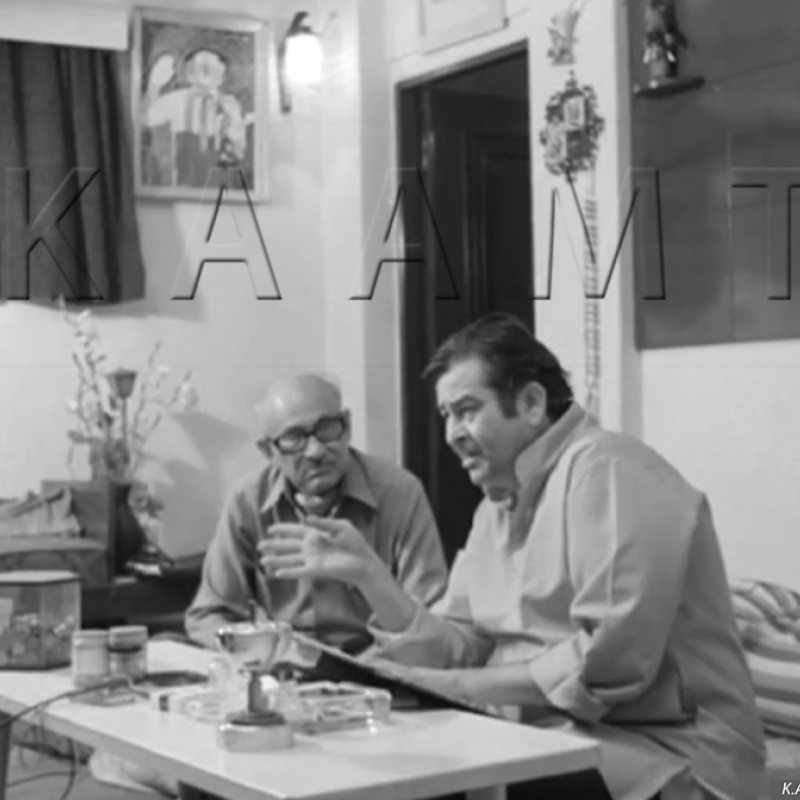

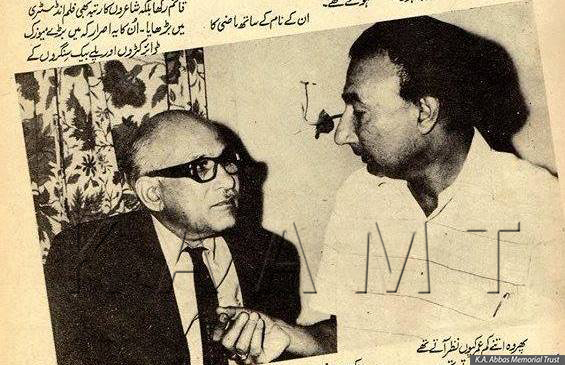

K.A. Abbas with Sahir Ludhianvi

Raghunath Raina evaluates Abbas’s contribution thus: ‘IPTA had a profound impact on the performing arts and many associated with it later joined films and contributed in giving a new dimension to cinema. Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, journalist, film critic, author, was one of the founder-members of IPTA. He wrote an autobiographical film Naya Sansar, about a journalist under pressure from tycoons…Abbas had another success when he persuaded V. Shantaram, who had himself pioneered a number of films of social concern, to produce a film based on his book, And One Did Not Come Back. The film Dr Kotnis ki Amar Kahani (The Immortal Story of Dr Kotnis/1946) was about a medical mission which the Congress Party had sent to China. Abbas has many firsts to his credit. His Dharti ke Lal (Children of the Earth/1946), based on an IPTA play was the first realistic film on rural indebtedness and dispossessed peasantry shown in the context of the Bengal famine. Munna (1954), the first Hindi film without songs or dances, was about a seven-year-old boy in a big city.

This is the third unique feature of Abbas’s work: that he was able to effortlessly deal with so many genres. In 1946, when the Second World War had just ended and film stock was hard to come by, the three pathbreaking films of the time were Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (Lowly City, which was the first Indian film to win the Grand Prix for the best film at the Cannes Film Festival), V. Shantaram’s Dr Kotnis ki Amar Kahani and Abbas’s own Dharti ke Lal, on the Bengal famine, all three of which involved Abbas.

Neecha Nagar charts the politics of water and the seepage of sewage water from the upper part of a hilly town where the elite live to the lower regions where the poorer folk live, causing sickness and death there. Incidentally, water remained an important concern with Abbas and he made Do Boond Paani (Two Drops of Water) on the scarcity of water in the deserts of Rajasthan in 1971. Neecha Nagar shows the power of collective action against exploitation, and has several references to the independence struggle. Dr Kotnis is a biopic that creates an image of India’s place in the world, like Pardesi (Outsider/1957) which was an Indo-Soviet production and was directed by Abbas and Vasili Pronin. The India, that once ‘gave’ Buddhism to China, is now sending medical aid and doctors to help them in their war against Japan.

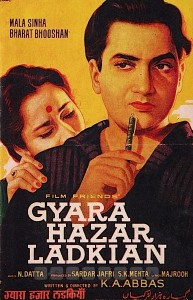

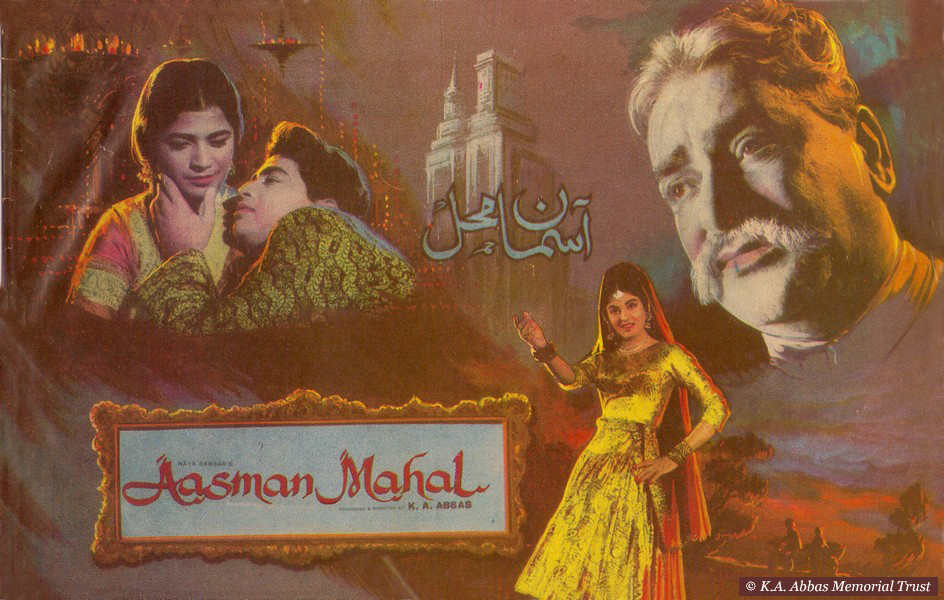

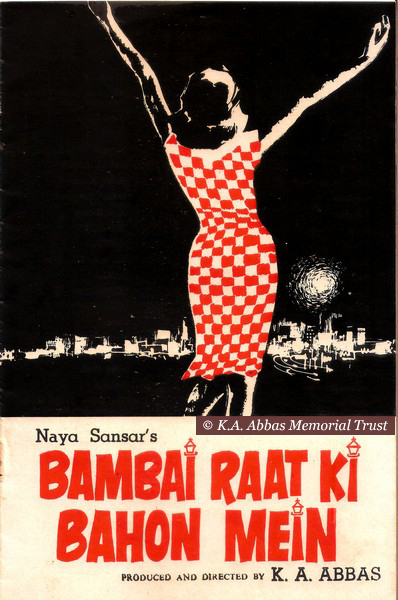

Abbas took up urban themes, particularly on the working class. His 11000 Ladkiyaan (11000 Girls/1962) is an ode to working women in the city from secretaries to typists, nurses, and dancers in clubs. He was a director who did not ‘fix’ women in sacred and profane spaces. In his films one sees women and men watching dances or dancing in clubs very unselfconsciously. Like Nasir Hussain, who usually sent his women protagonists on an excursion to the hills, thus ‘de-homing’ them, and placing them in the spaces of hotels and guest houses, Abbas, too, dispenses with the ‘home’ as being the ultimate defining space for the woman. Journalist Amar Kumar’s wife in Bambai Raat ki Baahon Mein (In the Arms of the Bombay Night/1968) returns to her father’s house and stays with him for three months because she is tired of her husband’s idealistic ways. Even the Rajasthani village girl in Do Boond Paani is more educated than her husband. The poor servant’s daughter in Aasman Mahal (Sky Palace/1965) too is educated and is a match for the Nawab’s son in shero-shairi (poetry). To Abbas goes the credit of also co-writing the first cross-border love story Henna (1991), as also dealing with the issue of Naxalites in 1980.

K.A. Abbas also subverted the genre known as the Muslim social. The Muslim historical and social had a very special place among the genres in Hindi cinema in the ’50s and ’60s. Aasman Mahal tells the story of a nawab in Hyderabad, who is unable to look after his ancestral mansion and has mortgaged it but resists all attempts to sell it off. His son is a good-for-nothing alcoholic who keeps pawning off invaluable jewellery from his own house. He is transformed when he meets the daughter of one of the servants. He confronts his father who won’t let him get married to a commoner and starts working as a mechanic, much to the horror of his parents. When the mansion is finally confiscated and auctioned off, the Nawab jumps off the terrace. The final shot is of the son, his wife and mother going away in a truck. The transition from one political system to another and the clinging onto the past is shown and critiqued. What is more important, however, is that he has also critiqued the genre of the Muslim social, predominantly focused on love, tehzeeb (culture), the life of the tawaif (courtesan) or courtly and royal encounters with the common folk. Abbas has shown a very different way of handling a difficult transition for the nawabs, who no longer have political power or patronage in the new democratic dispensation, and of presenting the passing of the old, not only in terms of nostalgia and tragedy, but also with the optimism for a future where people can earn their living through hard work.

The Auteur’s Style

The themes Abbas dealt with in his films ranged from the directly political—The Naxalites, the fight for Goa to wrest it from the Portuguese in Saat Hindustani (Seven Indians/1969), to the social (the passing of an age as in Aasman Mahal, the life of the dispossessed, the street-dwellers, the migrants, the ills of casteism, the empowerment of women, linguistic and religious issues, corruption as in Chaar Dil Chaar Rahen (Four Hearts,Four Paths/1959), or Bambai Raat ki Baahon Mein, choices that are made rightly or wrongly as in Achanak (Suddenly/1973) where a soldier cannot distinguish between killing in war and killing in the private domain to the biological (Dr Kotnis), and the ecological/environmental (Neecha Nagar, Do Boond Pani).

These issues were clearly placed in the larger framework of nation-building and the creation of a thinking polity. Bambai Raat ki Baahon Mein stands out for its charting out of the streets of the city which are to be covered by the protagonists in the course of a night that will change their lives. The city is the chief protagonist of the film and Abbas characteristically begins with the problems of the slum dwellers being documented by the journalist Amar Kumar. From the slums we are taken to the professional space of the newspaper office, the flight to Seth Daleria’s house, where Daleria tells him that both of them share the job of keeping track of each other and makes him a job offer he cannot refuse.

The narrative is split between the fate of two characters: one is Amar, and the other, an orphan making his way in the world, in his own words could be Johnny, Jamshedji or Jamaluddin. Abbas has a flair for taking the protagonists through spaces not often seen in the Hindi cinema of those times: spaces of modernity such as airports, mortuaries, cafes, fashion shows, clubs, modest middle class homes and the homes of the very rich. Amar and Johnny keep bumping into each other through the night and as events unfold, Johnny’s character meets with disaster, as speeding in his flashy car he knocks down a tea seller, while on the other hand Arun Kumar and his wife take the high road by rejecting an offer made by Seth Daleria for a luxurious and carefree life. Bambai Raat ki Bahon Mein is a film that still inspires films years later like Is Raat ki Subah Nahin (There is No Morning for this Night/1996) and others, but remains pathbreaking in the way it portrays the city of Bombay as the lead character, with the destinies of the protagonists made subordinate to the larger logic of the system.

His characters belonged to the new age and often reflected its contradictions. Journalist Amar does not immediately turn down Seth Daleria’s offer for a better and lucrative life. He takes a whole night to decide. One of the most important characters he has created is that of the ‘fool’. The foolishness of the fool arises out of a disjunct between the character and the social circumstance he is thrown into, or that he migrates into. This character first makes his appearance as Shri 420 (Mr. 420/1955), where Raj Kapoor creates a composite persona of the bumpkin-cum-Chaplinesque tramp, who has a wisdom and innocence that triumphs over the bad world outside. It reaches its peak in Jagte Raho (Stay Awake/1956), which Abbas co-wrote with Shombhu Mitra (who also directed it) and Anil Mitra.

Raj Kapoor in Jagte Raho

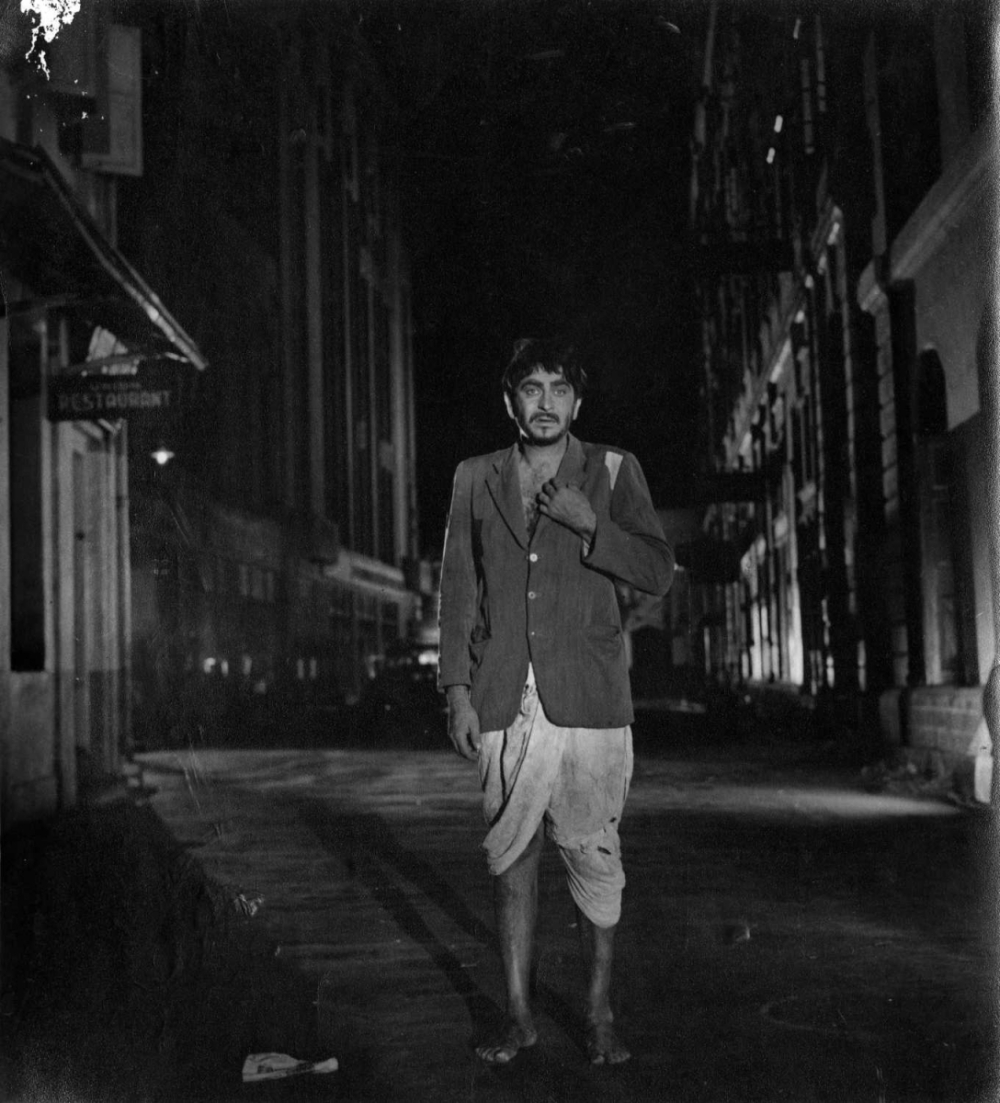

Jagte Raho deals with the nation metonymically through the building complex. The housing colony is used to effectively put across the idea of keeping alert and defending the new nation from internal enemies. A migrant, the poor son of a farmer, enters a housing complex looking for water to drink. The inmates take him to be a thief and organise themselves into a group, to search the houses and capture the thief. The community here is thus bound together only spatially and not by any profession. The residents’ army sets out to look for the thief and the police too join in. A panorama of nefarious activities that go on under the cover of respectability is uncovered: the brewing of illicit liquor, printing of counterfeit notes, the ill treatment of women, the murderous intentions of the corrupt rich and their lackey accomplices.

The inhabitants of the block, with all their intended aggression and vigilance are ineffective in catching the real culprits, the anti-social elements within their own fold. The poor thief who is being hounded is unwittingly witness to all these illegal activities. He is mute and terrified and on the run out of fear; but in an effective reversal breaks into speech when the crowd catches him. He addresses them by declaring his innocence and speaks out against the corruption he has witnessed. Jagte Raho in this respect is unique among Hindi films, not just in its engagement with social realism, but also in that this moment of speaking out does not prove to be an agent of change. The passive and silent observer speaks and the crowd continues to hound him as before.

Raj Kapoor in Jagte Raho

It is only in the end that he moves out of the building block having evolved to a new consciousness of himself; without having changed either the people around him, or his surroundings. His new-found timid confidence is also a silent one, unarticulated. Though he is not an agent of change, he has, in all innocence, disrupted a whole range of nefarious activities, not through active intervention, but by merely being a ‘passive disrupter’.[2] This character is unique in Hindi cinema.

This ‘fool’ then mutates into the joker of Mera Naam Joker (My Name is Joker /1970), where Raj Kapoor now plays the clown in the circus. This is a fictional biopic that traces the unrequited love of the clown, and the pain behind the laughter. While this film encapsulates the international handshake that both Abbas and Raj Kapoor wanted to give to the Soviet Union, the film lacks the social punch of Shri 420 and Jagte Raho. Nonetheless, the character of the wise fool, which has had many mutations in the Hindi cinema, had Abbas as its foremost creator.

Another distinguishing feature of his work is the way in which he eschews melodrama for realism. This probably explains why the scripts he wrote and co-wrote were mostly big hits, while his own films did not do well at the box-office. The reason is not just that he took up off-beat themes, or he focused on the have-nots, or that he did not always use stars. I think the reason is also that he deliberately avoided melodramatic buildups with correspondingly climactic soundtracks, camera movements and mise-en-scenes. Even when there is a high point, the emotion does not dovetail with the dominant ideological positions, thus distancing the reception of the peak moment. Nimmi’s insistence in Chaar Dil Chaar Rahen is an example of this: the tawaif who should be happy she has found an honourable man to marry her, throws it all away by insisting that her mother stay with them once they are married, because, as she says, women like her mother only have their daughters to support them. Even the villain in Anhonee, Om Prakash, who blackmails the sisters, is finally deprived of the very root of his villainous behavior, because the sisters’ story is so complicated that his blackmail won’t work anymore. The final denouement is between the sisters and not, as would have been melodramatically satisfying, between the villain and the good, lead protagonist.

Songs were an integral part of his films but not in a stereotypical way. The songs bear the imprint of IPTA. Some of the important picturisations in his oeuvre are songs of the community, of the collective, that show people working and toiling together. This is a genre of songs that contributed to the ‘gold’ of the golden period and has gradually disappeared from our screens today. The use of Hindi, Urdu and English by his protagonists also underscores the multilingual reality of our country. This was quite deliberate, as is evident from the fact that Abbas used actors from a given state to play characters from another state in Saat Hindustani (Seven Indians/1970).

Conclusion

Abbas’ vision was a modern and progressive one, and this was reflected not just in the stories he told but the way in which he told them through his cinema. This modernity was firmly embedded in the nationalist struggle, and the consequent tasks of nation-building, reform and development. What makes him a unique filmmaker is that he was the first person to straddle the worlds of both commercial as well as parallel cinema and to leave behind impressive bodies of work in both realms. For all these reasons and more Abbas remains a unique figure in the Hindi cinema, having blazed many trails that people started to follow only decades later. He remains unique for his political vision and commitment as well as the aesthetic choices he made.

Notes

[1] A concept brought into critical focus by Ranajit Guha in his writings. His ‘On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India’ accused the dominant historiography on Indian nationalism of leaving out ‘the subaltern classes and groups constituting the mass of the labouring population and the intermediate strata in the town and country—that is, the people’. Guha’s essay inaugurated the widespread use of the term ‘subaltern’ in postcolonial studies, which he defined as the ‘demographic difference between the total Indian population and all those we have defined as the elite’

[2] Stuart Hall uses the concept of ‘passive disrupter’ in another context, but I find the phrase aptly describes the character of Raj Kapoor in Jagte Raho: ‘…in spite of the fact that the popular masses have never been able to become in any complete sense the subject-authors of the cultural practices in the 20th century, their continuing presence, as a kind of passive historical-cultural force, has constantly interrupted, limited and disrupted everything else.’

References

Guha, Ranajit. 1988. ‘On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India’, in Selected Subaltern Studies, eds. Ranajit Guha & Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hall, Stuart. 1996. ‘On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall’, in Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, eds. Dave Morley & Kuan-Hsing Chen. London: Routledge.

Raina, Raghunath. 1987. ‘The Context: A Social Cultural Anatomy’, in Indian Cinema Superbazaar, eds. Aruna Vasudev & Philip Lenglet. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House.

Vasudev, Aruna. 1986. The New Indian Cinema. New Delhi: Macmillan India.