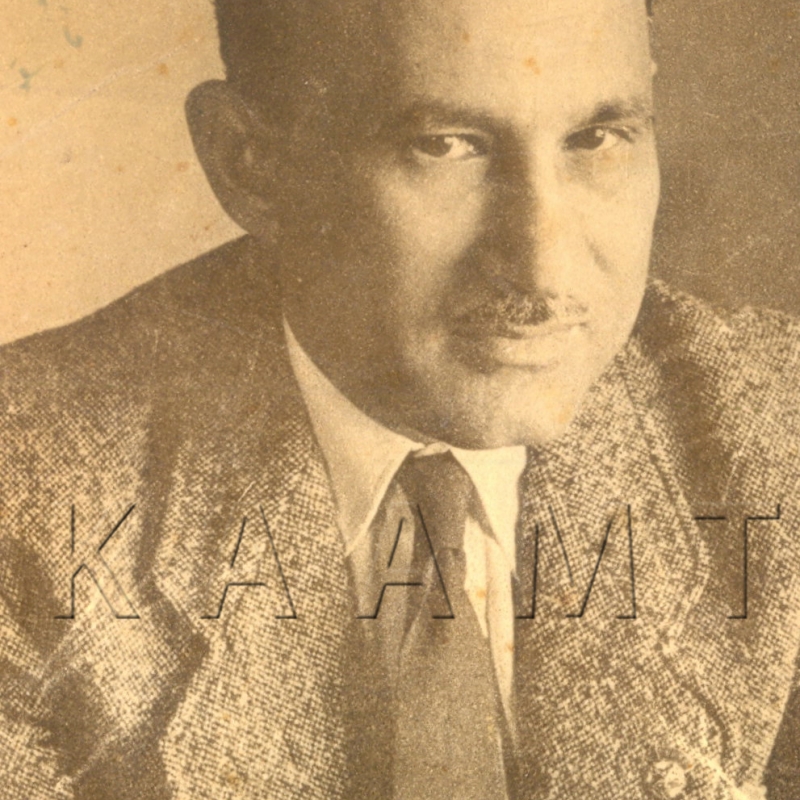

The 212-page compendium on Khwaja Ahmad Abbas tells a refreshingly sober and engaging saga of this noble and courageous man, a champion of socialist causes and hallowed human values. Several eminent personalities come together to tell tales of their encounters and moments of instant pull towards him or those of their lasting friendship with him. Dr Syeda Hameed, a close relative and co-editor, sets the ball rolling by opening the door to her earliest childhood memories of his films, professional achievements, travel exploits and her own frustrations when, in order to ‘resurrect’ him, she visited his flat with a few others looking for ‘his most prized and treasured books and trophies’, but ran into empty shelves.

All his films and almost all his books were missing. Even the Pune-based Film and Television Institute of India reported either ‘missing reels’ or some available ‘smelly’ stuff. Worse news from a friend startled them when he stumbled upon Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s magnificent play on Mahatma Gandhi and the English version of his Urdu novel Inquilab (later translated into German, Russian, Ukrainian, Azerbaijani, Czech, Kazakh and Hindi) with a kabadiwala (scrap dealer).

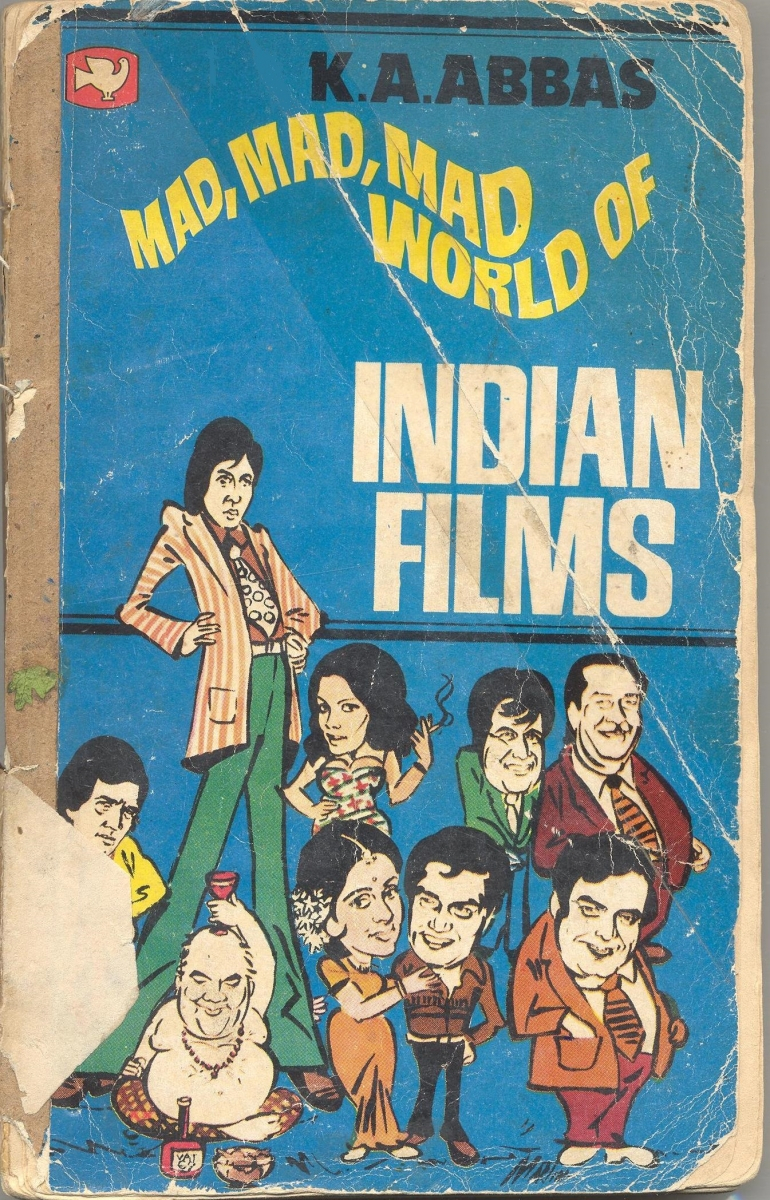

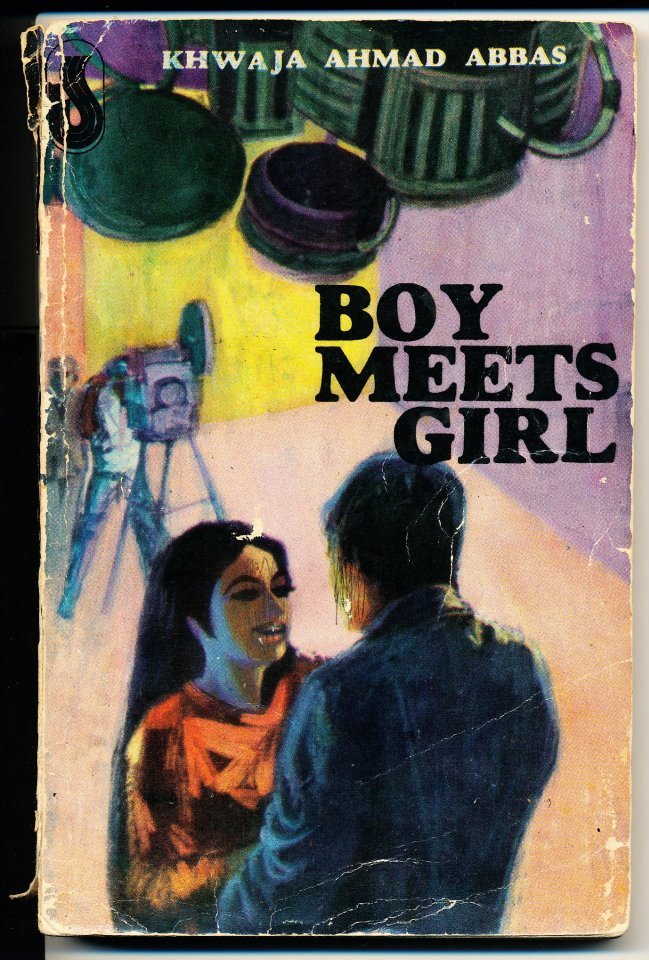

There are profiles by others, such as those who worked with Khwaja Ahmad Abbas during his Bollywood journey and went on to become popular matinee idols, or fellow comrades, who met him head-on (for a time, even fell foul of him) and literary men who dekko-ed him, eyeball to eyeball. Also included are some of his best stories, his own pieces on socio-political issues, and interviews with famed writers like Krishan Chander, which reveal his beliefs and dreams.

The prime time of Abbas’s work coincided with the period in India’s post-Independence history when the erstwhile Soviet Union had embarked upon a novel, first-ever ideological experiment in the world, namely, that of building a society along Marxist lines. Millions across the globe believed that the experiment would end the centuries-old perverse economic structure in which the rich always exploited the poor. Perhaps, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas saw hope for India too in that endeavor.

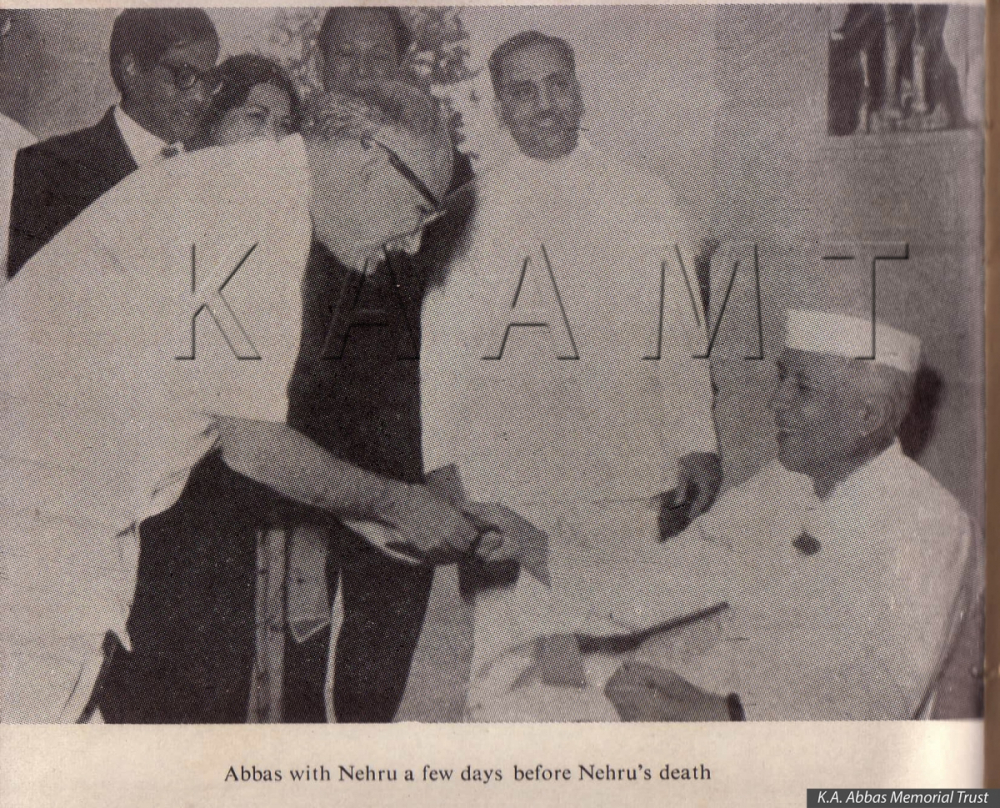

Concurrently, Nehru happened to be at the helm of affairs in India—a political hero Khwaja Ahmad Abbas loved and adored, who also fought for justice and equality for the impoverished though from a different ideological platform. Given Nehru’s favourable impression of the rapid strides made under the Soviet model and his own well-known sympathies for Marxist economics, the air in India was abuzz with slogans of ‘Hindi, Russi–Bhai Bhai’. Indeed, Nehru’s idea for a Planning Commission of India is said to have been inspired by the central planning machinery installed as part of the Soviet command economy.

Two early powerful influences appear to have shaped the core of Abbas’s personality: one an ancestral line of intellectuals and social reformers on both his maternal and paternal sides; and, two, his exposure to the sensitive analysis in Munshi Premchand’s books of the socio-economic existence (or non-existence) of the poor peasantry and factory workers and their ruthless exploitation by the wealthy class.

The unique individuality of Abbas (in the non-conformist and non communist sense) is brought alive in the compendium with vignettes from the period after he landed in Bombay to pursue his journalistic ambitions. Two city-based bodies, the Progressive Writers Association (PWA) and the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which matched the very life mission he had given himself as a collegian at Aligarh (‘Mujhe kuch kehna hai’, I want to say something) attracted him like magnets. These were largely dominated by communists from the CPI (the undivided Communist Party of India), their active cadres and several theatre men and women.

It was in their company that he had his first brush with Marxism and the Left movement in India. In popular perception, these groups were seen as ‘communist front organisations’, an image that disturbed Abbas. Not that he was not socialistic enough. His allegiance to a dynamic (not dogmatic) Marxist path for a society was total but his difficulty was that as a free spirit he could not persuade himself to surrender his freedom as an artist and creative thinker. Nor could he offer a cult-like loyalty to the ‘collective wisdom’ of the party or whims of the party bosses, which was a must for ‘a member of the family’. All he wanted was to take the ‘member’ out of this relationship. However, he was misunderstood and doubts about his sincerity began to be spread around. He was talked of as ‘a reactionary and bourgeois’ and eventually ‘expelled’ from both PWA and IPTA. Even a case was filed against him by some strongmen from the party for having written the introduction to a humanistic novel by Rama Nand Sagar, a non-communist.

Ten years later, the scales once again turned in favour of Abbas. He was invited to a meeting of the PWA, offered apologies by none other than his ‘ex-accusers’, and he an ‘ex-traitor’ and ‘a non-communist member’ was reinstated and voted to preside over the meeting. Thereafter, he continued to play an active role as a leading light of the group.

A prolific writer in three languages (Urdu, English and Hindi), the breadth and depth of his contributions are enormous: 74 books, 40 films, 89 short stories and 3000 pieces of journalese. A ‘truly human dynamo’, as he is very aptly described by Syeda Hameed. His story ‘Sparrows’ was included in a West German anthology of the world’s best short stories. Only two others were selected from India, one authored by Rabindranath Tagore and the other by Mulk Raj Anand. Along the way, he also garnered several other literary and film awards, including the President’s Gold Medal for Shehar aur Sapna.

The list above, I believe, is only illustrative, not exhaustive of all his contributions. After all, by his own admission (Hameed and Fatima:50) he once chanced upon, after a lapse of 10 long years, the manuscript of his short novel The Walls of Glass lying hidden in a heap of old papers. This gives rise to the vague feeling that perhaps not all his writings have been accessed and counted, thereby prompting the hunch that the actual tally of his contributions could be higher.

He was also a widely recognized columnist as the author of the ‘Last Page’ for Blitz, a left-wing weekly which ‘blitzkrieged’ the machinations and scams of the private sector, the right-wing political groups supporting it as well as social evils like communalism. Through his eloquent pen, Abbas enthralled and inspired lakhs of his regular readers every week.

Perhaps, the most illuminating part of this volume lies (for me, at least) is in the way it reveals his moral fibre and the courage of his convictions. He was no armchair socialist but one of the few who actually practised what he preached. I would say that the socialist ethos is more spiritual and idealistic as well as less materialistic, and therefore demands self-denial of a higher order and an iron will in terms of its implementation, unlike the capitalist creed, which largely abets greed, crime and exploitation. Abbas humbly embodied this, both in his private and public self. For instance his living conditions at home were spartan; he was a teetotaler, he owned no private property, he eked out his living by freelance journalism or script-writing for films, and he didn’t make films with profit as their raison d’etre but only to communicate his ideas to the masses and to educate them.

In respect for these values, major artists and technicians would often not charge him any money but had the earnings received from the distributors divided amongst them later. At times, moving to outdoor locations for shootings, he would travel third class, sleep on hard floors in small government rest houses and use oil lanterns when there was no electricity. He wrote and made films about the city’s underbelly, associated himself with the rights of the lowliest workers on his film sets and took special care of them. He even found time to speak up for the helpless and unprotected sex-workers of Kamathipura in Bombay. Above all, he never wrote short stories or novels for money, though some money came to him anyway as an honorarium.

Bombay might have served as a strong stimulus to unleash his ideas in his three major spheres of work but it was, in my view, Aligarh that acted as the actual incubator of that drive and fire in him. His familiarity with contentious social issues through his self-study and learning from literature, participation in debates, and face-to-face connect with the misery and despair of the agrarian poor in villages close to his university, all came to him when he was studying there. Most students, moving from their childhood to young adulthood are generally seen as experiencing and enjoying the ‘springtime’ of their lives. Abbas was a far cry from them. He was fast turning into a man on a mission. Thus, from a tender age, the poverty and suffering of the downtrodden seemed to deeply move and agonise him: the hallmark of a true socialist.

Kudos to the two editors (Iffat Fatima being the second one) for their exceptional efforts in gathering these fond memories of K.A. Abbas by staunch friends, intellectuals and colleagues, covering his struggles, the dreams he worked on and his accomplishments. The result is an elegantly produced and powerful ‘tribute’ to a man of many parts. Getting into his house and finding ‘emptiness’ all around must have been like stepping into the wilderness. Nonetheless, they continued to exert themselves with a lingering sense of optimism and, finally, managed to capture a life which enriched many others in so many wondrous ways.

Lal Salaam, Abbas Sahib.