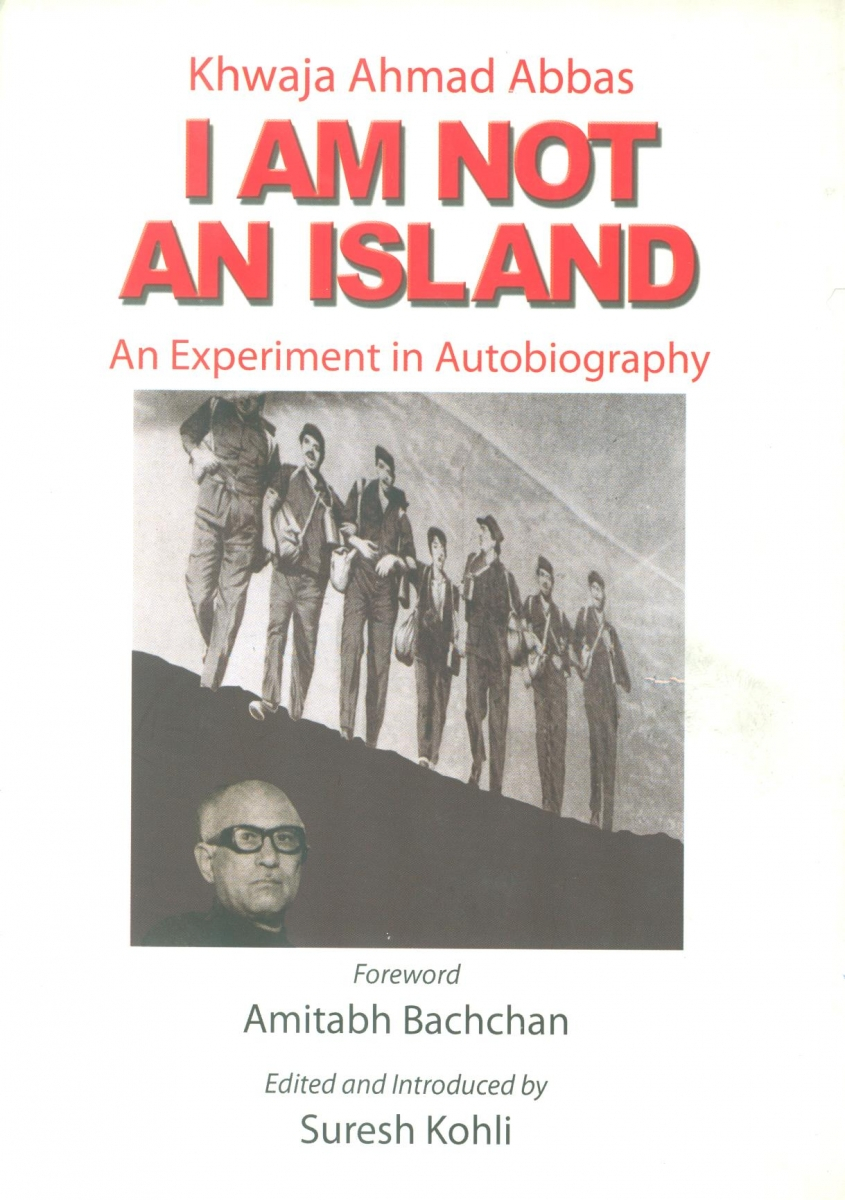

In his delightful autobiography I am not an Island, this is how Khwaja Ahmad Abbas describes himself:

This rotten fruit called K.A. Abbas has dropped from a unique family tree of saints and sinners, murderers and marauders, timid recluses and adventurers, soldiers of fortune and defenders of faith, poets and farmers. I got travel from my maternal grandfather, Commander Ashraf Husain who joined Holkar's Army, my rebellious and non-conformist spirit from my grandfather who was almost blown from the mouth of a canon, and going further back, is my furious social justice which I got from one of my ancestors—to ‘kill’ rather than suffer the ignominy of bending the knee before tyrants.

Many lenses can be used in tracing the entity called Khwaja Ahmad Abbas. In this article, I want to look at Abbas through the prism of the music and lyrics of his films.

Abbas, the man, was a lifelong missionary—that is the clear verdict of history. He uses his art as an unstoppable vehicle for social reform. This determination drives his stories, novels, journalism, plays and most prominently his films. When he writes stories for master filmmakers like Raj Kapoor, it is the same reformist impulse which drives him. He rues the fact that Raj Kapoor diluted his stories and made them first and foremost mass entertainment. In his interview to his lifelong colleague and friend V.P. Sathe, Abbas says, ‘The least tampering Raj Kapoor did to my story was in his film Awara. After that it was more Raj, less Abbas.’

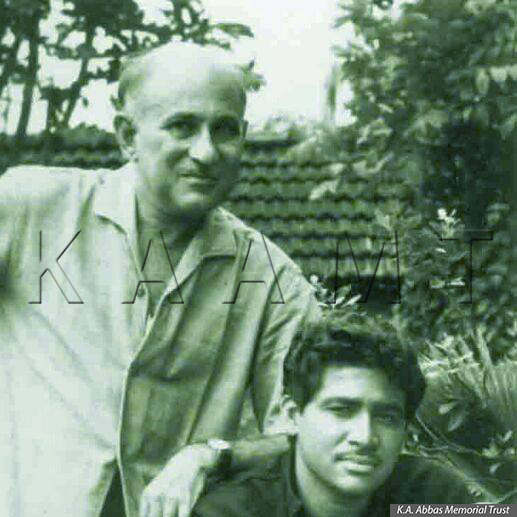

With V.P. Sathe and Raj Kapoor

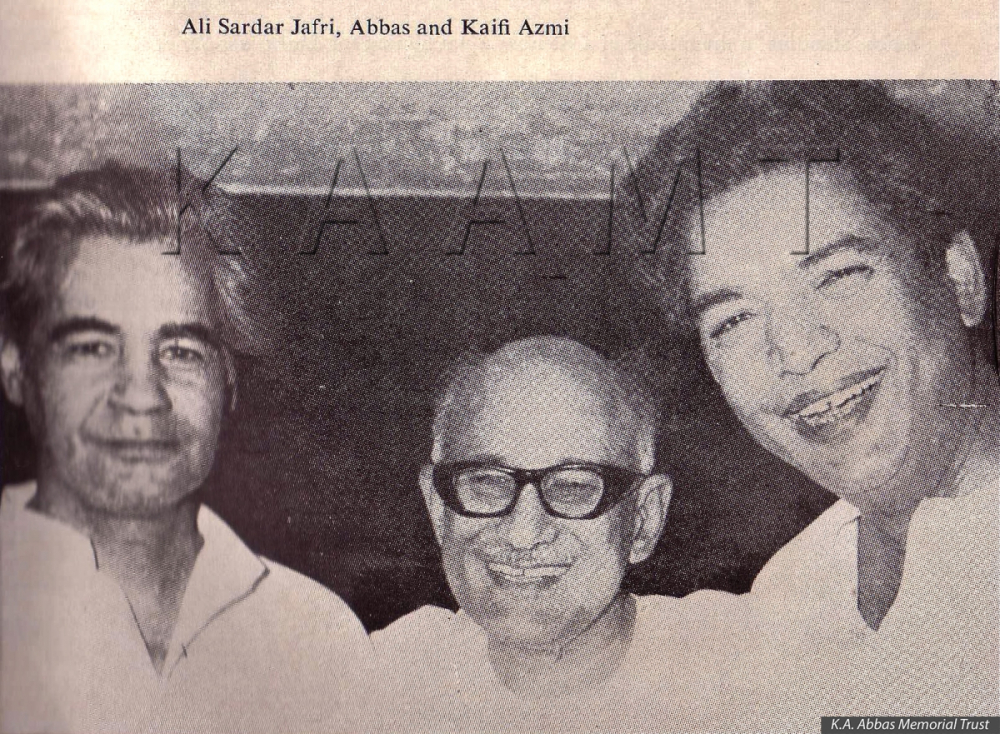

Songs had a very special place in his films. He was probably the only director who gave equal weight to music and lyrics. If I was to try reading his mind, I am sure that he wanted his songs to be remembered as poetry, not ‘filmi lyrics’. That is what they were; by every standard they were the finest nazms and ghazals ever written for films. The best poets of the 1960s and ’70s wrote for Abbas’s films, and that too for very little money: Ali Sardar Jafri, Kaifi Azmi, Majrooh Sultanpuri and Prem Dhawan, to name a few.

There is no record of what came first in his films, music or lyrics. What is clear, however, is that both were always subservient to his script. Throughout his life he remained faithful to the same two or three music directors. A majority of his films had music by Anil Biswas, an artist and friend he deeply respected.

I will reconstruct the sequence of events of his brainstorming baithaks to the best of my recall. His practice was to call late night sittings at which he narrated his new story sequence to his core group of intellectual buddies, which included the poet and music director. Together they would flag parts that could be embellished by song. It was that moment which gave birth to the music and lyrics. It was a collective effort and a combined effort.

His early films are imbued with patriotic fervor. This is not to imply that this sentiment is confined only to his early work. It can be traced throughout, though in varying measure. The first film he wrote was for Bombay Talkies in 1941 called Naya Sansar, starring Ashok Kumar and Renuka Devi. Its title became inspirational for the unit, which led to his naming his production house, ‘Naya Sansar’.

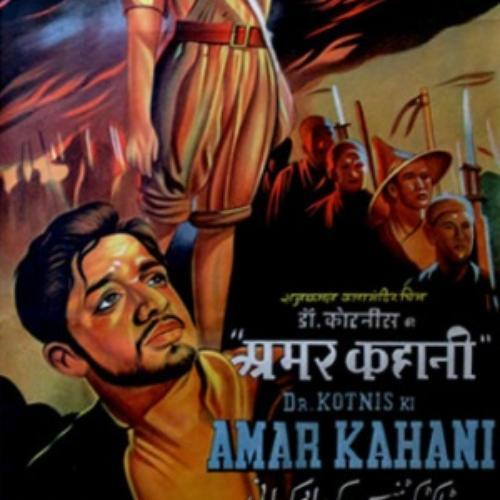

Abbas made Dr Kotnis ki Amar Kahani (1946), which was inspired by the story of Dwarkanath Kotnis, who went to China on a medical mission with a team of Indian doctors. The title role of Dr Kotnis was played by V. Shantaram, in the role of the young doctor from Maharashtra, who joins the Chinese struggle against imperialism and marries a Chinese girl, played by his real-life wife, Jayashree. He ultimately dies of a disease contracted from his patients in the mountains of Yunnan. Songs of the film were written by Deewan Sharar and set to music by Vasant Desai. The first song is a cry for freedom, which is led by the Chinese heroine as a wake up call to her people. As was the practice, Jayashree herself sings the song; playback singing had not yet become popular:

Ghulam nahi tu josh mein aa

Ye desh hai tera hosh mein aa

You are not a slave, wake up!

This is your country, wake up!

The context is China but its inference to the Indian freedom struggle is evident. The second song evokes nostalgia for home in foreign lands. The setting is a gathering of the six doctors who return home after an arduous workday, and fondly recall their far off villages. They play this song on a gramophone with a swirl-cone speaker:

Pardesi re kahay chhoda mora desh

O traveller! Why did you leave my land?

Between laughter and tears they listen to Zeenat Begum's plaintive voice captured in the 78 rpm gramophone record.

Dharti ke Lal (1946), the first cinema of realism in India, the original print of which lies in Paris archives, is regarded as one of 100 best in world cinema. It was made in 1946 under the IPTA banner. The film is set during the 1943 Bengal famine. Abbas writes that he was inspired by Bijon Bhattacharya’s Nav-Anna (Nabanna,The New Harvest) and the IPTA play Antim Abhilasha (His Last Desire), plus Krishan Chander’s Annadata (The Bread Giver). Nav-Anna was turned into a play by Sombhu Mitra in which he also played the lead role.

Lyrics for the film were written by Abbas’ friends, Ali Sardar Jafri, Prem Dhawan, Nemichand Jain and Vamiq Jaunpuri. Another landmark in this film was its music, as it was the first film score composed by Ravi Shankar. It evoked the pathos of men, women and children dying of starvation and the white rage of the revolutionaries who saw them die. Black-and-white frames, using light and dark images and montages were a first in Indian cinema. The song reflecting this tragedy is sung by Mumtaz Shanti and filmed on Tripti Mitra. She plays a young woman displaced in the big city along with her family. She first resorts to begging, then to selling her body to stave off starvation. Each line of its songs is twined with Abbas's philosophy, as is seen in this powerful song:

Ab na zuban par taley dalo

Jee ka haal sunaaney do

Dil ke khoon ko aansu ban kar

Aankhon se beh jaane do

Tumko kya tum rang mahal mein

Aish karo aaraam karo

Bhook ke maarey marney waley

Marte hain mar jaaney do

Don't lock our tongues

Let’s speak out our hearts

Let the heart's blood trickle down

In strings of tears

What's it to you?

You luxuriate in pleasure domes

Starving dying humans

If they're dying, let them be

Abbas dreams of the day when the farmer will return to the land from which he has been alienated. In the film there is a shot of a young couple in a village mela (fair). An old man sings in IPTA mode of the joys of returning to Mother Earth. Black-and-white shots of people, their collective gestures, joys and sorrows all carry the trademark Abbas touch. The lyrics are from an old IPTA song, written by one of the four poets, we don't know which one. Its refrain ‘Jai Dharti Mata Jai Ho’ (All hail Mother Earth) reverberates with love for mother earth:

Yehi maati mein jiye hum log

Yehi mein maran hain bhaiyya

Sagri poonji yehi dhan hai bhaiyya

We lived in this earth

In this earth we will die

This is our saving, our wealth

Wamiq Jaunpuri is identified as the poet of another song of Dharti Ke Lal, which expresses the theme of the film. The IPTA chorus sings ‘Bhooka Hai Bangal’. Its lyrics are from a longer poem of the same name by Wamiq. Lashing out at society, which watches starvation without flinching, Abbas and his friends—poets, artists and musicians—make their scathing social comment in lines such as these:

Peeth se apna pet lagaye lakhon ulte khat

Bheek mangney se thak thak ke utrey maut ke ghat

Jiyan maran ke dand milaye baithey hain chandal

Bhooka hai Bangal

Nadi naaley gali dagar par laashon ke ambaar

Muththi bhar chaawal se yaaron sasta hai ye maal

Bhooka hai Bangal

Growing hunger, death stalking

Tired of begging, bed turned over[i]

Chandal waits to transport the corpse

Bengal starves

Lakes, streams, drains, piled with corpses

This stuff is cheaper than one fistful of rice

Bengal starves

In 1952 Abbas made Anhonee with the top star couple Nargis and Raj Kapoor. The question of identity is raised here in the persona of the identical half sisters Mohini and Roop (Nargis's first double role) who are exchanged at birth. One is the offspring of the legal wife, the other of a sex worker. The ‘wrong’ one is raised in the household of a judge and the ‘right’ one in the kotha (brothel) of the sex worker. The same theme was used in his story Awara, which he wrote for Raj Kapoor. His own film Anhonee, which fared relatively, better than his other films at the box office, had three dances. They were filmed on Nargis as Mohini, child of the kotha.

Here again Abbas and Ali Sardar Jafri teamed up with music director Roshan to lash out at the piety of high society. Mohini, her birthright to a respectable household restored by the sacrifice of her sister, cannot stop herself from performing a mujra (dance of the courtesans) before the polite gathering of city elites. Predictably, they are outraged at this spectacle and the song mocks this hypocrisy:

Sharifon ki mehfil mein dil gaya chori, dil gaya!

Choron ki aadat ko hum jaan paaye

Woh dekho woh baithey hain aankhen churaiye

Jaise hum hi hain jinhone in ke heere churaiye, moti churaiye

Jebein tatolo sahib dil gaya chori dil gaya!

In this gathering of the genteel, my heart has been stolen

I know the habit of these pretenders

There they sit, eyes downcast

As if we have stolen their diamonds, their pearls

Search your pockets dear Sirs, my heart has been stolen

Thus, Abbas and Jafri, both reformists, expose the genteel kotha frequenters who attend respectable gatherings and pretend to be shocked when the kotha is transported to the drawing rooms.

Next came Rahi (1953) set in Assam, a film about tea garden workers. The theme of the film is inspired by Mulk Raj Anand's Two Leaves and a Bud. Abbas was obsessed by the dispossessed, in this case the migrant labour who are working in tea gardens. Rahi offered an excellent setting for a two-edged sword with which to slash the abusive white masters of brown tea workers. Its first edge strikes at oppression, which the British owners of the bagan (garden) rain on the workers. They do not themselves wield the whip hanging on the wall. For this they hire a smart young native, Dev Anand, who has to keep workers in line. Its second edge strikes at the colonial project of tea manufacturing, which forces people to leave their homelands in search of livelihoods. The migrants, while they work under the whip, long for what they had left behind. By now Abbas had discovered the musical genius Anil Biswas, who would remain with him for the rest of his life. The lyrics were written by another lifelong friend, Prem Dhawan and poet, Dashrath Lal.

The eponymous song ‘Ek Kali Do Patiyan’ is filmed on the women tea pickers who sing while they reminisce about home. Achla Sachdev, a wonderful presence in all Abbas films, carries her baby in the basket, hidden among the newly picked leaves:

Chhod chhaad kar des ko apne aaye des paraye

Paapi pet ne dekho humko kya kya rang dikhaye

Jab ghar ki yaad sataye humse ek pal raha na jaaye

Leaving our own land to a strange realm we came

Our hungry stomachs revealed so many facets

Whenever we think of home we’re restless to return.

And along the hundreds of tea slopes scores of tea pickers pick up the words until this song of protest resounds in all the tea gardens:

Ek kali do patiyan janein hamri sab batiyan…

Hamri kamiya pe mauj udaye bairi

Hum hi ko ankhiyan dikhaye re bideswa

Khoon paseene se bagiya ko hum seenchein

Baithey baithey hukum chalaye re bideswa

The evil one squanders our earnings

And glares at us, the damned foreigner

We nurture gardens with blood and sweat

He barks out orders, the damned foreigner.

The foreigner (the bideswa) is draining the country and its most precious resource, its people, to fuel his development. Very early in his career (1939) Abbas had lashed out at the bideswa in his condemnation of the Hollywood blockbuster, Gunga Din, which he considered a resounding slap on the face of an enslaved nation. He wrote a review in the February 1939 issue of Film India, ‘It is an imperialist propaganda of the most vulgar sort and depicts Indians as nothing but the most vile barbarians. It will make the stomach of every Indian and every fair-minded foreigner turn with disgust. Some of the scenes in it are revolting. Nauseating.’ The same anger erupts in Rahi in the song that follows ‘Bideswa’. It is an anthem of resistance. Men tea workers pick up the refrain from the women workers and what is then born is another ‘brand Abbas’ song:

Zulam dha le tu sitam dha le

Hamare bhi to din hain aaney waley

Lagaye ja tu kodey hamein tan tan ke

Har ek ghao boleyga zubaan ban ke

Labon pe lageinge kab talak taley

Hamare bhi to din hain aaney waley

Torture us, oppress us

Our day will come, at last!

Use your whip on our bodies

Every wound will speak out

Until when will our tongues be locked?

Our day will come at last!

The workers then invoke the landscape of the tea garden to take up the cause of their oppression:

Ye kali kali tere liye khar banegi

Ye patti patti tez talwar banegi

Ye daali daali le ke aiyegi bhaaley

Hamare bhi to din hain aane waley

Each bud will turn thorn for your flesh

Each leaf will turn a sharp-edged sword

Each branch will carry a spear

Our day will come at last!

Pardesi was Abbas’s most ambitious and unique venture. It was the first Indo-Soviet film made during the years of India and USSR’s overtures of common cause and undying friendship. Made in 1957 with an Indo–Soviet cast, it starred Nargis, Balraj Sahni and Padmini. Its hero was a Russian actor Oleg Strizinhov who played Afanasi Niketan, the first Russian to travel to Indian shores. Balraj played Sakharam, a troubadour from the Konkan coast, where Afanasi’s ship landed. A strong bond of friendship was forged between the two.

Its music was created by Anil Biswas and lyrics by Abbas’s two dearest friends, Ali Sardar Jafri and Prem Dhawan. Two of its songs are anthems for new India, an India free of caste and class; the dream of the progressives. The first is a song by Sakharam, the bard, who witnesses his Russian friend being thrown out of the temple by the Mahants. He places his arm around the shocked and disheartened traveler and leads him back to the temple entrance with a song on his lips, which berates them for their bigotry:

Mujh mein Ram tujh mein Ram sab mein Ram samaya

Sabse kar le pyar jagat mein koi nahin hai paraya

There is Ram in you, Ram in me

Give your love to all, no one is a stranger

Na woh mandir, na woh masjid, na Kaaba Kailash

Mann mandir mein dekhle moorakh

Prabhu to tere paas

Pathar mein to Hari miley insaan mein dekh na paya

Sabse kar le pyar jagat mein koi nahin hai paraya

He is neither temple nor mosque, neither Kaaba nor Kailash

Look inside your temple–heart, find him residing there

In stone you discovered Hari but not in human beings

Give your love to all, no one is a stranger

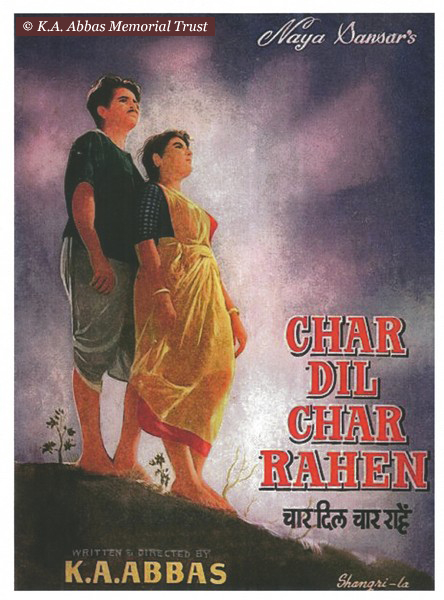

In 1959, Abbas made Char Dil Char Rahein, his first, and what he declared would be his last, multi-starrer which once again framed social issues such as caste and class. The film has four stories, which intersect at a chauraha (four-way crossroads). In one story, a dancer Pyari played by Nimmi is summoned to perform at the haveli (mansion) of a zamindar (landlord), Anwar Husain, who suffers from chronic insomnia. She sings of the ‘give and take’ between the tawaif (courtesan) and her client, where each one wants to extract his/her share. The lyrics by Sahir Ludhianvi are set to music by Anil Biswas. In this case, the theme of the song lashes out at the hollow norms of the social elite:

Koi maane na maane magar jaaneman

Kuch tumhe chahiye, kuch hame chahiye

Whether you believe it or not, my love

You want your share, I want mine

The second story in the film is of Govinda and Chavli, an Ahir boy and a Dalit girl, whose childhood friendship blossoms into love. This is Abbas’ scathing attack on caste. To prevent their inter-caste marriage, the villagers set fire to Chavli’s hut so she can burn for her sins. At the end of the film, the four stories converge at the crossroads in interlinked destinies. A new road would now be built by all the characters featured in the four stories. The film is about collective effort which will destroy caste and class hierarchies, and which would ultimately construct the road to a new India. Sardar Jafri’s poetry is the song of this new hope. The music of Anil Biswas is the people’s anthem, which surpasses anything ever written in this idiom:

Kadam kadam se dil se dil

Milaa rahe hai ham

Watan mein ek naya chaman

Khilaa rahe hai ham

We are walking in step, hearts beating together

A new garden is being seeded in our land

The song then heralds a new social order, which will be new India:

Saathi re bhaai re

Ham aaj neev rakh rahein hai us nizaam ki

Bike na zindagi jahaan kisi ghulaam ki

Lutein na mehanatein pise hue aavaam ki

Na bhar sake tijoriyaan koi haraam ki, saathi re bhaai re

Brother, Companion

We are laying today the foundation of a system

Where the life of a slave is not for sale

Where the labour of oppressed populace is not plundered

Where criminals cannot fill their coffers

Saathi re bhaai re

Utha liya hai ab samajvaad ka nishaan

Alag alag na hongi ab hamari khetiyan

Chalengi sabke vaste milon ki charkhiyan

Zameen se aasman talak uthengi chimniyan

Kaha tha jo wo karke ab dikha rahe hai hum

Brothers, companions

Today we are holding high the insignia of socialism

Our farms will no longer be fragmented

For one and all the mills will run

Their chimneys will rise from earth to sky

We are delivering on our promises

The theme of class is once again presented in Aasman Mahal (1966), which is the story of breakdown of the feudal order and the rise of the working class. Time has worn down the grandeur of Aasman Mahal. Its benign patriarch, the Nawab, played by Prithviraj Kapoor wistfully watches the decay. His son, Salim falls in love with Salma, daughter of a rickshaw puller. The pride of Aasman Mahal, literally meaning ‘palace in the skies’, is rubbed in dirt roads where the lowly rickshaws ply. At a mushaira (poetry gathering), Salma and Salim find themselves on opposite sides in a poetry competition. Once again, the class paradigm is played out through the words of Salma’s poem, which rejects Salim’s love since she thinks it is based on ancestral wealth, albeit a family now nearing penury:

Khwab daulat ke garibi ko dikhane wale

Asmano mein mahal apne banane wale

In khilono se na behlegi tabiyat meri

Itni aasaan nahi ai dost mohabbat meri.

You who show dreams of wealth to poverty

You who build your palaces in the skies

I am not amused with these toys

My love, O friend, is not so easy

The film ends with the auction of Aasman Mahal and the death of the Nawab who has ordered his wheelchair to be taken to his terrace to watch the bidding. This auction is foregrounded by the marriage of the servant’s daughter with the master’s son, the ultimate levelling of class. The lyrics were written by Sardar Jafri and this song is sung by Madhukar, with music direction by J.P. Kaushik. The madness of time is symbolized in the person of a fakir (ascetic) played by the superb actor Madhukar, whose prophetic lines are interspersed with the mujra in the Mahal, which is being held to celebrate Nawabzada Salim’s nikah:

Waqt ki bajti hai aahan

Har taraf hu ka hai aalam

Ta na na ya ya hu

Saab mahal khaak mein mil jaate hain laashon ki tarah

Soona reh jaata he aangan

Ta na na ya a hu

Allah hu Allah hu

Time's gong resounds

Everywhere is dead silence

All castles like all corpses become dust

The courtyard empties out

God only God only God

In 1962 Abbas and Ali Sardar Jafri jointly produced a film based on the working girls of Bombay, Gyarah Hazar Ladkiyan. It had music by N. Datta and lyrics by Sardar Jafri and Majrooh Sultanpuri and was directed by Abbas himself. The credits flash the name of Faiz Ahmed Faiz but there is no clarity on his role because of the bad print of the film. The theme song of the film is a tribute to a woman’s role in the workplace. Its idiom is remarkably modern and deeply cognizant of the dignity of women who haul the dual burden of home and of work:

Kaam ki dhun me hai ravaan

Gyarah hazaar ladkiyan

Aati hain daftaron mein ye

Fasle bahar ki tarah

Padhti hain khushk filein

Nama e yaar ki tarah

Naach rahi hain ungliyan

Bol rahi hain churiyan

Gyarah hazaar ladkiyan

Moving, absorbed in their work

Are 11,000 girls

Arriving in offices

Like the wafting breeze

They read their dry files

As they would lovers’ letters

Fingers are dancing

Bangles are speaking

Of these 11,000 girls

These are girls from the working classes in the big city. But there is another category of women and girls, the homemakers, whose work is never counted, never recognized. Majrooh Sultanpuri wrote a song in tribute to these women. There is another poem on the exact same theme written by Kaifi Azmi but Abbas has used Majrooh’s lyrics, which celebrate womanhood as no one had ever done before, the male voice celebrating the quintessential female:

Meri mehboob mere saath hi chalna hai tujhe

Chaand se mathe pe mehnat ke pasine ki lakeer

Jaag uthi jaag uthi Hind ki soi hui taqdeer

Kat ke gir jayegi pairon se purani zanjeer

Ladkhadaeygi kahan tak ke sambhalna hai tujhe

Kone kone main sulagti hai chita tere liye

Teri dushman hai teri naram ada tere liye

Zehr hi zehr hai duniya ki hawa tere liye

Rut badal jaye nazar aise badalna hai tujhe

Meri mehboob mere sath hi chalna hai tujhe

You, my beloved, will have to walk along with me

Line of perspiration on your moon-like forehead

Slumbering destiny of Hind awakens

Old chains will sever and drop from your feet

How long this faltering? Steady yourself!

Every corner a pyre burns for you

Your softness itself is your enemy

This world for you is poison

Change your view so your aura changes

You, my beloved will have to walk along with me

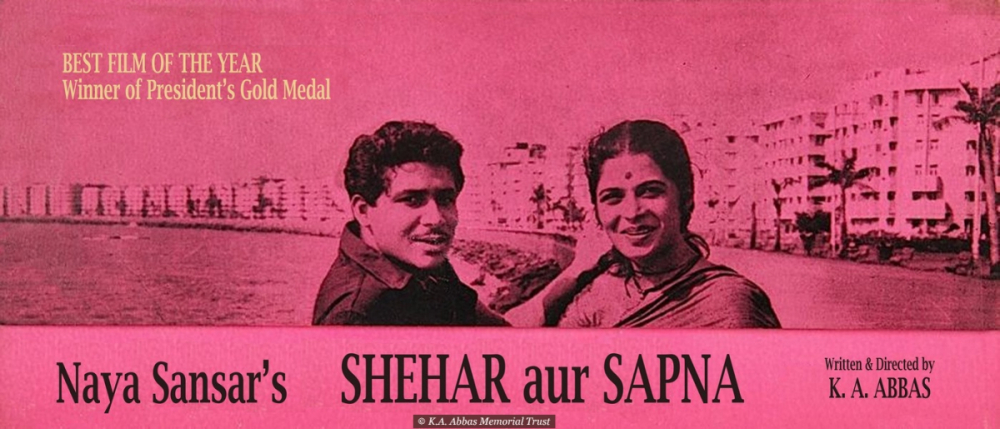

With Dilip Raj

His next film Shehar aur Sapna, with lyrics by Ali Sardar Jafri, was released in 1964. The film is about urbanisation and displacement. The main characters are a young couple; the boy is played by Dilip Raj, one of Abbas’s favourites, and son of his friend, Jairaj. The girl, Surekha Parikar, was an Abbas discovery and acted in several of his films. They leave their respective villages and come to the big city in search of a livelihood. Many films have since been made on this theme, but it was Abbas who made the first film about displacement. The most recent film on this theme was made by Hansal Mehta in 2015. His City Lights won the Producer’s Guild Khwaja Ahmad Abbas Award for the most socially relevant film of the year.

In Abbas’s film the boy and girl are in identical circumstances. In the concrete jungle of Mumbai, they are unable to find a place to live. So they create their home inside one of the many unused drainpipes. Their displacement from home leads to tensions and friction in the relationship, which is compounded by the harshness of the big city. One song in the film is sung by the one and only Manmohan Krishna, actor and singer unparalleled. Ali Sardar Jafri has written this dirge, which seems to give voice to all displaced persons:

Hazaar ghar hazaar darr

Ye sab hain ajnabi magar

Khabar nahi ki ab kidhar

Mudegi apni rehguzar

Yahan se jayenge kahan

Amaan payenge kahan

Ye zindagi ki behisi

Ye behisi ki zindagi

Thousand homes thousand anxieties

All around is strangeness but

Unknown in which direction

Will now our path turn!

Where will we go from hence

Where will we find refuge

This life of indifference

This indifference of life

The second song, sung by Manmohan Krishan is a metaphor for hope even times such as this when displacement shatters relationships and love withers away. It is sung by a bard and directed towards the protagonists Dilip Raj and Surekha:

Pyar ko aaj nayi tarah nibhana hoga

Hanske har dard ko, har gham ko bhulana hoga

Aansuoon se jo bujhe jate hain aankhon ke chirag

Khoon e dil deke unhe, phir se jalana hoga

Abhi khil jayenge, masle huye kuchle huye phool

Shart bas ye hai ke seene se lagana hoga

Voh jo kho jaye to kho jayegi duniya sari

Voh jo mil jaye to saath apne zamana hoga

Love will need a new impetus

All pain will have to be borne with a smile

Tears are extinguishing lamps of eyes

They will be rekindled with the heart’s blood

Withered flowers will bloom again

Only one condition, hold them in your embrace

If she is lost my whole world is lost

If she is found I own the entire world

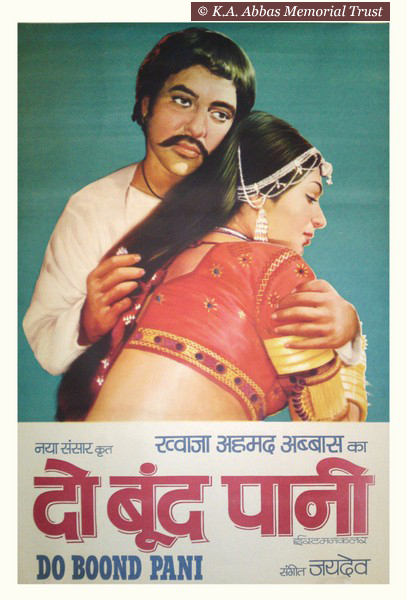

Do Boond Pani (1972) is set in the desert of Rajasthan and focuses on the problem of water scarcity. In 1972, almost half a century, before the world woke up to this crisis, Abbas spoke through his film about humanity’s most challenging problem. It is a story set in the dunes of Rajasthan where women travel up to 10-15 kms to fetch water. The song that encapsulates the water crisis is written by Kaifi Azmi and sung by Mukesh. It is foregrounded by villages, which slowly empty out because of drought. This compels people to migrate to areas, which are hostile and alien. One such person is Jalal Aga the protagonist, who leaves his new bride and his old father while he goes in search of a project, which will enable him to bring back water to his parched village. As a kafila (convoy of travelers) leave their homes, the song reverberates in the desert:

Apne vatan me aaj do boond pani nahi

Do boond pain nahin to yahan zindgani nahin

Tod ke saare rishte naate ja to rahe hai dhool udate

Pani jis din aa jayega laut aayenge nachte gaate

Hogi suhani kabhi shaam jo aaj suhani nahi

Do boond pani nahi to yahan zindgani nahi

Pyari dharti chhodein kaise

Kasme apni todein kaise

Marna hoga mar jayenge jeete ji munh modein kaise

Chaha jo uthna kabhi baat ye dil ne mani nahi

Do boond pani nahi to yahan zindgani nahi

In our land we don't have two drops of water

Without two drops there is no life

Breaking all bonds we are leaving, raising dust

When water comes gushing we will return dancing

One day our evenings will be beautiful again.

Beloved land how can we leave?

How can we break our bonds and promises?

We will die if we must, but living-death, no!

When we get up to leave our heart is pulling us back

Without two drops of water there is no life

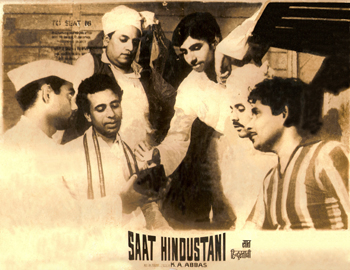

In 1970 was released Saat Hindustani, a film about the struggle for the liberation of Goa by seven young revolutionaries from all over the country. Abbas chose this thematic for the dual purpose of resistance and national integration. Each of his seven characters plays roles, which are opposite to his/her own regional, linguistic and religious identity. For example, Amitabh Bachchan plays an Urdu poet from Uttar Pradesh, Anwar Ali. Anwar is modelled on Abbas’s friend of Aligarh days, Asrarul Haq ‘Majaz’. Jalal Agha who came from the Irani community of Bombay played a Marathi powada (balladeer) singer. The resistance and yearning for freedom, which was so important to Abbas, was reflected in the lyrics of Kaifi Azmi set to music by J.P. Kaushik. Kaifi and Abbas speak with one voice to celebrate and encourage freedom fighters to pursue their mission despite the oppression and torture inflicted by the enemy. Kaifi Azmi’s words express the spirit of the seven revolutionaries:

Zulm hadd se badhega to ghat jaayega

Apni talwar se aap kat jayega

Rang laayega nanhi kali ka lahu

When oppression overreaches its limit

It decreases

By its own sword it is severed

Blood of the newborn bud will bring results.

These are the opening lines of the main nazm, which is freedom’s cry sung by the magnificent seven as they plan to ambush the Portuguese and liberate their beloved land. Kaifi Azmi’s lyrics have been forgotten with the passage of time but from the forgotten film clips or a book of poems whenever one reads or listens to their words and musical rendition the heart soars with an emotion, which is difficult to express in words:

Yun badho jaisey lehra ke dhara badhey

Thokrein khao to dil hamara badhey

Iss tarah badhke toofan mein rakho qadam

Ke qadam choomney ko kinara badhey

Ek taraf maut hai ek taraf zindagi

Beech se le chalo karvan sathiyo

Aandhi aaye ke toofan koi gham nahi

Hai yehi aakhiri imtihan sathiyo

Move forward like a strong current

Stumble but move, so we can take heart

Step in the storm in a manner such that

The shore rises up to kiss your feet

There is life on one shore, death on the other

Chart your caravan’s way by striding the water’s midst.

This is the final test friends

Har taraf dushmani ka andhera bhi hai

Har qadam par ghareebi ka dera bhi hai

Sirf raatein hamari nahin hain siyah

Dhundla dhundla hamara savera bhi hai

Jaisey shola bhadakta hai bhadko kabhi

Hota jaata hai gehra dhuaan sathiyo

Everywhere the blackness of enmity

Every step the seat of poverty

Our nights are dark but beyond darkness

From the shadows arises our dawn

Like the flame, burn bright and brighter

The smoke has become too dense

Life’s philosophy revealed through poetry has been the poets’ forte right from Greek bards to Sylvia Plath, John Lennon and Bob Dylan. Abbas has the unique quality of revealing his life’s philosophy through his films by using the vehicle of poetry. His lived at a time when people lived, ate, drank, loved, slept, earned, spent all for a passion called Azadi. When Azadi was achieved they were thrown into the inferno of communal killings and displacement. This invariably became their subject matter. No matter where they lived in the subcontinent, their mental landscapes cohered—thereby making their art stronger. Everyone of Abbas’ friends was drawn to the big bad city where all their passion was to play out in various art forms. So also this small man from Panipat who traced his ancestry from Sufi teachers, and was child of pious and enlightened parents. Bombay was too far from Panipat and film was considered an indulgence which was best avoided. But Abbas was true to his origins by bringing to his films in every aspect especially through songs the values that had quietly found a way into his child-heart.