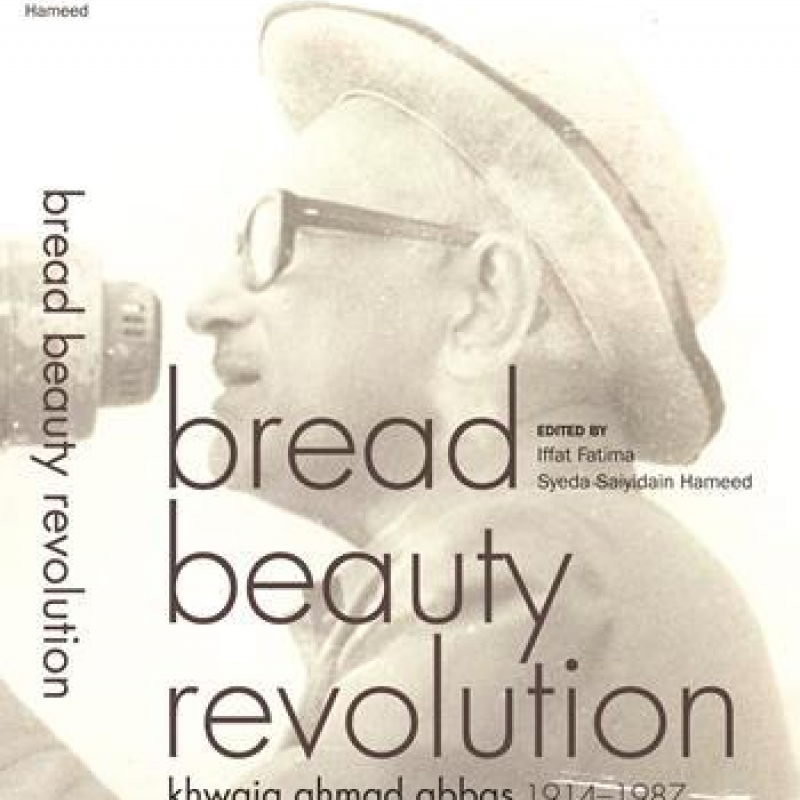

A review of Bread Beauty Revolution: Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, eds. Syeda Saiyidain Hameed and Iffat Fatima, a compilation of writings by a towering intellectual of Nehruvian India (first published in the Friday TImes, June 10, 2016)

The year 1914 was very kind to the Indian subcontinent. Despite being the opening year of the first of the two World Wars that were to devastate the 20th century, at least seven great personalities from the worlds of music and literature were born in this region alone: Begum Akhtar, the silver-throated nightingale; the worker-poet Ehsan Danish; Krishan Chander, one of the four pillars of Urdu fiction of the 20th century; Gul Khan Naseer, the Faiz Ahmad Faiz of the Balochi people; the historical novelists Aziz Ahmed and Naseem Hijazi; and Khwaja Ahmad Abbas.

While the birth centenaries of Krishan Chander and Naseer were celebrated to a limited extent in Pakistan, the same cannot be said of the other personalities mentioned above, including Abbas.

Khwaja Ahmad Abbas (1914–87) occupies a distinguished and distinct place in subcontinental letters, especially in the Progressive tradition. June is the month of Abbas, as he was born on June 7, more than a century ago and passed away on June 1, less than a week short of his 73rd birthday. A contemporary of such luminaries as Saadat Hasan Manto, Ismat Chughtai, Rajinder Singh Bedi and Chander, he is remembered today as the writer of such memorable short-stories as Ababeel, Barah Ghante, Captain Rafiq ki Maut and Sardarji (retitled as Meri Maut after a storm of protests from both India and Pakistan); the creator of at least one epic novel, Inqilab, and a very readable autobiography I Am Not An Island: An Experiment in Autobiography; and the screenwriter, producer or director of such memorable, classic arthouse films as Neecha Nagar, Dharti ke Lal, Awara, Pardesi, Saat Hindustani, Mera Naam Joker and Bobby, which either introduced or made more famous some of the enduring stars of the Bollywood firmament like Raj Kapoor, Meena Kumari, Amitabh Bachchan and Shabana Azmi.

Added to that was his prominent role as a journalist, historian and documentarian of Nehruvian India and an indefatigable champion of an India which was both secular and progressive and where freedom of expression was sacrosanct. In terms of sheer productivity and prodigiousness, the only comparison which comes to my mind is the great Bhisham Sahni [1915–2003], whose birth centenary is still being celebrated: he was a son of Rawalpindi, writer in Urdu, Hindi and English, fellow-Progressive of Abbas and author of the great Partition novel, Tamas.

Born in Panipat to a family descended on the maternal side from one of Urdu’s great reformist poets, Altaf Husain Hali, and on the paternal side from a similarly reformist family, Abbas entertainingly recounts the circumstances of his birth in an excerpt from his autobiography included in the book titled Abraham and Son: how taking advantage of a family wedding, his father took away the infant Abbas, leaving a note behind which said that unless the marriage expenses were drastically curtailed and simplified, both the former and latter would starve themselves to death. In this manner, according to Abbas, ‘social reform came to our family, and our town…this must have been the first successful experiment in emotional blackmail for the cause of social reform.’

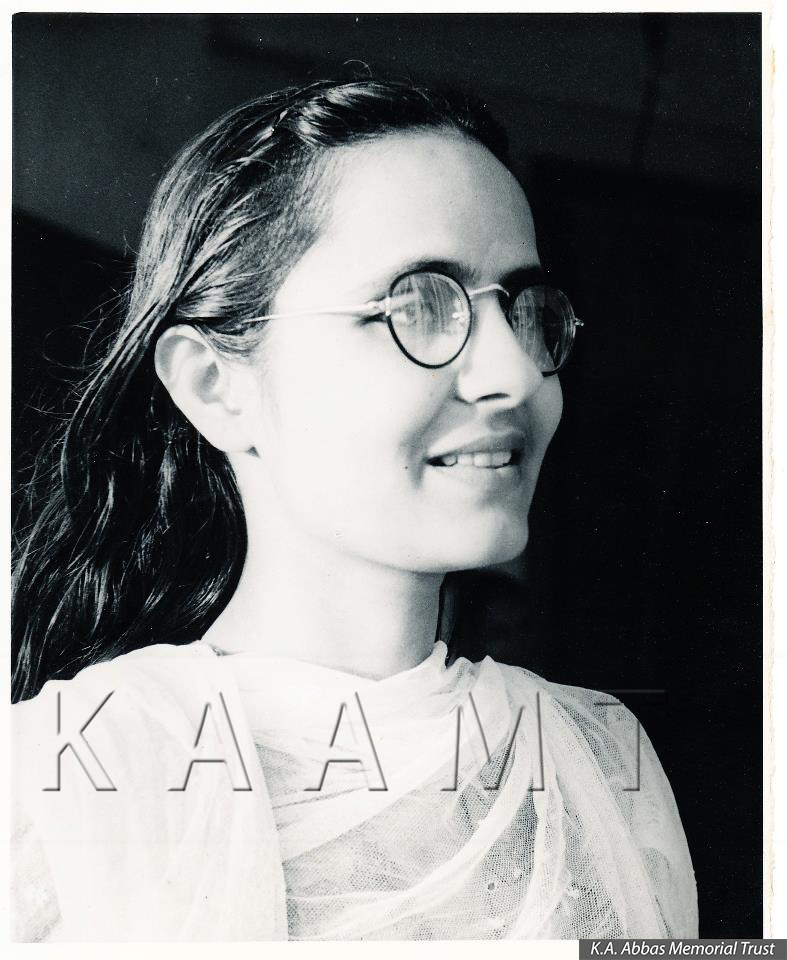

Abbas’s marriage to Mujtabai Khatoon (Mujji) is also recounted hilariously in the excerpt titled ‘The Taste of Marriage: Mujji’ where the latter cheerfully confesses to the former that she never said ‘Yes’. Someone among the women had shaken her head and so she could say that they were not properly married at all. And Abbas would retort that that was all right with him since it freed him from the responsibility of paying her any mehr [customary payment in the form of money or possessions made by the groom to his bride].

Mujji

There are three valuable interviews of Abbas with collaborators and comrades like V.P. Sathe, Krishan Chander and from the Indian Literary Review, where one learns valuable details about Abbas’s early life, his influences, his relationships with eminent personalities like Jawaharlal Nehru and Raj Kapoor, and his views on literature and film.

Reading these interviews, I suspect many would not have known that accompanying Abbas on his first ever meeting with Nehru was a fellow student from Aligarh, a young man named Sibte Hasan, who later became one of the leading lights of the Communist Party of Pakistan; or the very interesting circumstances in which Abbas was expelled from the Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA); and the fact that it was Abbas who persuaded Nehru to put pressure on the Pakistani government to pardon Sajjad Zaheer and allow him to return to India. I was also happy to read Abbas’s praise for Krishan Chander’s collection of Partition stories Hum Vahshi Hain, which according to the former ‘did have some sobering influence on people at that time'.

A very interesting and relevant inclusion in Bread Beauty Revolution is the chapter titled ‘Perils of Progressive Literature’ which recounts the storm of protests Abbas had to face following the publication of his short story Sardarji in the eminent Lahore-based journal Adab-e-Lateef in 1948. The story, which was a satire on communalist Muslims, was pilloried in Pakistan and also by the Hindu and Sikh communities in India, owing to a skewed and incomplete reading. Abbas was labeled everything from a ‘Muslim Leaguer’ to a Pakistani agent and even an agent of British imperialism.

The piece includes moving accounts of how Abbas ended up in Kashmir, reading his story out to a bunker full of doubting Sikh officers, very close to the Pakistani forward positions, and who upon hearing the story made him an honorary Sikh. It also narrates how Abbas managed to assuage a Sardarji, who had served a notice to Abbas to appear in court, by reading the whole story out to him after obtaining a case postponement of two hours. What happened to Abbas is indeed very relevant to the illiberal atmosphere currently prevalent in both countries, epitomised by the war against dissenting intellectuals and students on both sides of the border.

Though Abbas was one of the leading lights of the PWA and the iconic Indian People’s Theatre Association, as well as one of the godfathers of Indian ‘parallel cinema’, he did not have a trouble-free relationship with the Communist Party of India (CPI), much like many of the other prominent members of the PWA such as Manto, Bedi and Chughtai. His column titled ‘Communism and I’ recounts how the PWA expelled Abbas from its fold, following the former’s preface to Ramanand Sagar’s Partition novel, Aur Insaan Mar Gaya. Abbas’s crime was that he had encouraged the CPI to introspect through ‘a scientific psychological probe’, regarding the responsibility for the horrors of the Partition and the bloodbath that followed, laying the blame squarely on both Indians and Pakistanis.

What happened to Abbas in India also happened to Manto in Pakistan, when in addition to writing Siyah Hashiay, he had Muhammad Hasan Askari, an ex-Progressive-turned-reactionary write the foreword to the offending volume. However unlike Manto, Abbas was eventually re-admitted to the Progressive fold, albeit after 10 years of his expulsion. Here is how Abbas describes his relationship with the CPI and why he did not join it:

That is the crux of the dispute between the communists and I. The communists would like to turn the entire proletariat (subject to variations of the existing Party line or lines) militant and aggressive. I would like to tame both their militancy and their aggression with the poetry of Tagore, the verses of Iqbal, the prose of Premchand, Ismat Chughtai and Krishan Chander, the humanist philosophy of poets like Kabir and Sardar Jafri (whom I regard today as the modern avatar of Sant Kabir)…But then why do I not join the Communist Party? Because I am not prepared to sell my intelligence and my conscience to the so-called collective wisdom of the Party, or take diktats from a ‘cell’ or a group of opinionated or fanatical upstarts, as happened during my Aur Insan Mar Gaya inquisition. I believe myself to be Marxist—though I believe that Marxist methods be applied to the tenets of Marxism itself.

One of the best writings in the volume is Abbas’s English short story, The Black Sun, which beautifully captures the angst of the postcolonial moment by linking the national independence movements of the Irish and the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in India with the Algerian War of Independence and the Civil Rights Movement in the United States with the Korean War, before offering a sobering reflection on the murder of Patrice Lumumba in 1961 and with it the hopes of an entire continent and the role of the United Nations, ‘this grand mausoleum of man’s hopes, where every day peace and freedom are given a grand and solemn burial,’ as one of the Indian characters in the story pithily observes.

No memorial volume can ever hope to fully capture an active working life of 73 years encapsulating 74 books, 40 films, 89 short stories and 3000 pieces of journalism. However, this volume does it beautifully and is interspersed with both tributes by Abbas to towering personalities like Nehru and Meena Kumari, as well as tributes to Abbas himself by stalwarts like Amitabh Bachchan and Shabana Azmi, as well as reproductions of ‘Abbasiana’, such as posters of his various films, book covers, original handwritten letters and articles, and rare family photographs. An added pleasure are the selected couplets from Hali with their English translations given at the beginning of every chapter.

In the light of the information given in the bibliography that Abbas’s entire library was ‘mysteriously destroyed’ after his death, thus compounding the editors’ task, this volume is indeed a collector’s item. However, the only inexplicable thing is the absence of any samples of Urdu prose from Abbas, which would have enhanced its appeal for the connoisseurs.

Perhaps what is needed more than the publishing of this volume is a resuscitation of the work and legacy of writers and artists like Abbas in our troubled times; and for me a related question is also the following: why, despite his astonishing productivity across genres and his non-adherence to any ideology, is he not better known in our midst today? While we ponder this question, it would be fitting to conclude with a quote from Abbas’s ‘Last Will and Testament’:

I am still an AGNOSTIC—that is, I don’t know about religion. I believe in ONE GOD—therefore, I may be a MUSLIM. But ALL religions believe in one divinity. I think the whole humanity is one, and believes in ONE GOD who has no shape or form, therefore, I am inclined to believe that NATURE is GOD.