Recently I came across Khwaja Ahmad Abbas’s story ‘Rupiya, anna, pa’i’ (Rupee, anna, paisa) after many years and decided to teach it in my Advanced Urdu class at New York University. The students, who were ‘desi’ [a term used to describe a person of Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi descent living abroad], belonging mostly to families of Indian and Pakistani origin, had never heard of Abbas and only one knew what a rupee, anna and paisa were.

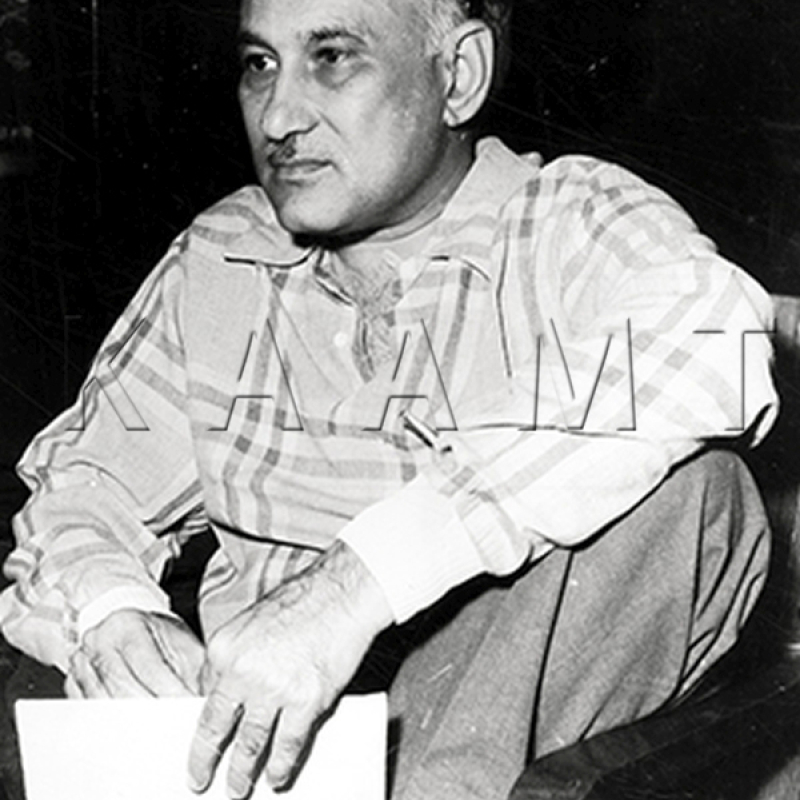

After an initial round of conversations about Abbas’s life, his literary accomplishments, his role in what was once Bombay Cinema and is now the Bollywood film industry as screenplay writer, director and film maker, his fame as the man who introduced Amitabh Bachchan in the actor’s first film Saat Hindustani (something the students could finally relate to), we turned to the story itself. What happened next made me feel a little like a mathematician on the eve of a great discovery.

A summary of the story is in order first. A young man arrives in Bombay from a village or small town somewhere, after mortgaging his family home, leaving the bulk of the money thus obtained with his mother and bringing the rest with him. He has recently completed his BA, he rents modest lodgings, buys used furniture, and begins the arduous task of finding a job. A great deal of money is spent on stationery for the applications, mailings, literary and film magazines, novels as well as his rendezvous with and courtship of a young girl Asha, whom he takes to see the film Anarkali three times and for whom he regularly buys flowers to wear on her hair and wrists. The money soon fizzles out; a loan is secured from the local moneylender, the courtship with Asha continues, no success yet with the job. Finally, the borrowed sum is also spent. The visits to restaurants with Asha come to an end, he starts selling off his furniture, and from his last entry we discover that he has bought a bottle of sleeping pills.

In and of itself, the plot is in no way earthshaking or noteworthy as such. Another young man with dreams of making it big in the big city bites the dust; the degree in his possession is of no value at all. Abbas was a socialist and as a member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement, he hobnobbed with the likes of Ismat Chughtai, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Krishan Chander, Saadat Hasan Manto and Kaifi Azmi, to name just a few of the stalwarts of the movement. Like them, he believed that the injustices of society dealt even well-intentioned and educated young men and women a blow. He was a realist in his writings and in his films he did not abstain from laying bare the ills of modern society, the pain and disappointment of those who lacked resources and wealth, of the men and women caught in the grip of modernization that often produced tragic results, exploitation of the masses by the elite class and the horror of poverty. All this is evident in this story as well. So what is it that makes the narrative a remarkable piece of fiction?

I will begin by saying that for students whose Urdu is not fluent, who have little knowledge of the histories of the subcontinent, who haven’t read much Urdu fiction or poetry, and have just had a semester on Manto for the first time, the story became gripping. But first a word about its format, technique and structure. It has been said that in it Abbas is experimenting with a new literary device. One could assume though that he is not experimenting but actually confidently using a device that he had come up with, being the brilliant screenplay writer and film maker that he was. A device that he thought would be minimalist in style and yet at the same time give so much detail that one would come away feeling one had read a long, complex story. So what is this technique?

The narrative opens with these lines:

A few torn pages from a notebook containing lists of earnings and expenditure, picked up from the pile of garbage in front of a raddi-wallah’s shop –

The reader’s first instinct is to regard these lines as a comment from the writer in his voice. The next line is the first entry, a date:

First January, 1953

Earnings

After mortgaging the house to Makhanlal sahukar

Expenditure

To mother for household expenses

The amount for each is in the corresponding spaces as the second column. There are two columns on each page, one consisting of a written description of what the money is spent on, the corresponding column presenting the actual numerical amounts that are spent or earned. Dates and months are diligently recorded. The conjecture that the writer has found this ledger dissipates once the reader moves on. The entries that follow are read by the students with a certain degree of skepticism. ‘So who found the ledger?’, ‘But this is an account ledger, this can’t be a story’, ‘How can a mature writer write such a silly story?’, ‘What made him think he could get away with it?’, ‘Was he writing a satire?’ are some of the questions they ask.

The idea of how a narrative should look in addition to what it contains is not new. But what is happening in Abbas’s story is unique. There is no human narrator, either in the first person or the third. No actual action takes place except that the items were recorded by a human hand. The ledger, in fact, is the narrator, and presents the narrative, a linear plot, following the events in the life of a young man unfolding from January 1, 1953 to December 13, 1953, a few weeks short of a year.

The only constant are the entries. As for the magazines and novels he buys at the railway stall, for those of us who have experienced any part of that era, they are familiar in terms of subject matter: Filmi Pariyon ki Kahaniyan, Jawani Deewani, Gunah ki Raatein, Zehr-e-Ishq. The magazines are well known: Screen, Filmfare, Shama Mastana Jogi. The brand of cigarettes he buys is Gold Flake. Later it’s Capstan and finally when the money is running out, he makes do with beedis. He and Asha see Anarkali at Novelty Cinema, later he buys her paan and flowers for her hair and wrists. We gather all this information just from the entries of items and their prices. The device within the device is to use familiar objects and places to create the background the reader needs to contextualize the protagonist’s life. Times of India, paans from Mahobay, the travels to the Employment Exchange in the tram, dinner at Apollo Bandar. No descriptive passages, no imagery, no deliberately wrought metaphors or symbols. Yet they are all there. Abbas could have put even Hemingway to shame with this sparse writing; this is absolute minimalism, but concealed in its starkness are clever and effective ploys to make the story extremely expressive and filled with images of life in Bombay.

So how do we read this story? I assigned my students different time periods presented in the text and working in groups they analyzed every entry as if they were decoding a puzzle. The process became an extremely engaging and interesting exercise. The most interesting item becomes the film Anarkali, released in 1953. A blockbuster starring Bina Rai and Pradeep Kumar, with music by C. Ramchandra, and songs written by Rajinder Krishan, Shailendra, Hasrat Jaipuri and Jan Nisar Akhtar. The film is memorable for the songs sung by Lata, and Bina Rai’s role as the doomed beautiful dancing girl in the Emperor Akbar’s court with whom the young prince Salim falls in love. The young protagonist is poor, but he is in love, and like any young South Asian man, has deep links with the cinema and no doubt identifies with Prince Salim, who was capable of such great love and passion. The fact that he takes Asha to see the film three times speaks to the fact as also to Abbas’s own relationship with cinema.

In addition, we are compelled to examine India in 1953. It was Nehruvian India; Partition, with its bloody conflicts had come and gone. But the new India was still reeling from the after-shocks of division and bloody rioting, and was trying to confront its Independence from 200 years of British rule. What was expected was not in view yet; poverty, injustice, feudalism and class inequality, were all a bitter reality in the new India. A young man from a small town or village, with a Bachelor’s degree in hand, still had no future. Desperation leads to hopelessness and hopelessness ends in suicide. Anarkali and its date of release are important for another reason as well that I will touch upon later.

The various parts of the story were then put together, using the third-person point of view. A new and very different form emerged, one that was more traditional, easier to understand and less cluttered in terms of shape and organization. We compared the two and although the students were happy with the story that had been re-structured from the original, they wrote in their essays that they preferred the original and perhaps would not have had so much fun if it had been written in a conventional style. They admitted this was the first time a story had gripped them in this fashion and I was asked to introduce more such Urdu stories in the syllabus. Alas, there are no others like it. Even Abbas himself didn’t pursue this style in which the objects in the story tell the story. These entries conclude the narrative:

letter to Asha via mail - 2 -

bottle of sleeping pills 2 12 -

offering to beggar - 1 -

Finally, I would like to come to a part of these teaching sessions that made us all return to the text and also initiated a new line of inquiry about it. I had made copies for the students from Diiya Jale Sarii Raat, a collection of stories by Abbas compiled and published in 1959 by Maktaba Jamia, Delhi. In this story, which I have used for my essay, the first date is entered as January 1st, 1953. One of my students, a young man who didn’t have a hard copy of the story went online to rekhta.org and searched for ‘Rupiya, anna, pa’i’ and found it, but to his surprise realized it wasn’t the same version that I had been using in class. I wasn’t concerned since stories often appear in different collections.

However, he brought something to my attention that made us all dive into another round of discussions. This version was from another collection titled, Khwaja Ahmed Abbas ke Muntakhab Afsaane, whose date of publication was 1988 and the collection had been compiled by Ram Laal. In the story in his collection, the first entry was January 1st, 1946, which puts the story a year before Partition in 1947. Abbas died in 1986 and could not have had a hand in the publication of this collection.

Editors will do odd things and tampering with texts is not uncommon. Chughtai’s story ‘Lihaaf’ has lost its last sentence somewhere along the way since it was first published. Manto’s story ‘Khol do’ has also lost its last sentence. Pakistani writer Ghulam Abbas’s story ‘Overcoat’ has had several areas chopped off and if one didn’t know it, one would accept these versions as authentic and complete. The above tampering is directly related to what some publishers/editors may have regarded as obscene, unpalatable, not fit for public consumption, etc. But why was the date in Abbas’s story changed from 1953 to 1946?

The film Anarkali becomes a test for the accuracy of the first version. The film was released in 1953 and hence the protagonist and his girlfriend Asha could not have been going to the cinema to see it in 1946. Ram Laal is a well-known writer of Urdu fiction and has also written criticism. In his Editor’s Note he writes a glowing tribute to Abbas, but does not mention the change. Why does the story appear with dates changed in the collection he compiled? There are a few other changes as well, in terms of the structuring of the columns where the accounts have been recorded. For a new reader of the second version, the story will have contradictions or misinformation that may seem unresolvable if not checked against the original. Others will accept Ram Laal’s version placing the events in 1946 since no one really carries around dates of film releases in their heads. I didn’t either, but knew the film had been made in the '50s.I have not been able to find any leads to this mystery, but if someone reading this does, please do tell.

No amount of research has yielded another story like this in the annals of Urdu or English literature. Perhaps we can regard it as a form of multimodal literature which, according to Alison Gibson (2012), presents ‘varied typography, unusual textual layouts…concrete arrangement of text for visual purposes…which often pushes at its own ontological boundaries in the form of metafictive writing…or through ontological masquerade in itself’ (, ). Abbas’s story is reminiscent of Jacques Derrida’s Glas (1974) in which the text is divided into two columns and although the resemblance to the Abbas story ends here, the purpose as Alison describes the deconstructive process, may be the same: it challenges familiar reading habits. Whether or not the idea behind the form of ‘Rupiya, ana, pa’i’ may have been something Abbas picked up from his readings of modern experimental literature, it is clear the actual form is his own and the manner in which he adapts it to tell a story that is rich and replete with twists and turns, a narrative not just centered on dreams and ideals gone awry, but a testament to the failure of society to fulfill its promise, is unique to Abbas.

References

Derrida, Jacques. 1986 [1974]. Glas, trans. John P. Leavey and Richard Rand. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press.

Gibbons, Alison. 2012. ‘Multimodal Literature and Experimentation’, in The Routledge Companion to Experimental Literature, eds. Joe Bray, Alison Gibbons and Brian McHale, pp. 420–34. London and New York: Routledge.