Lucknow’s built heritage reflects a confluence of Indo-Islamic, Persian and colonial influences. Each structure in the city narrates a story—of power, patronage, cultural exchange and artistic evolution.

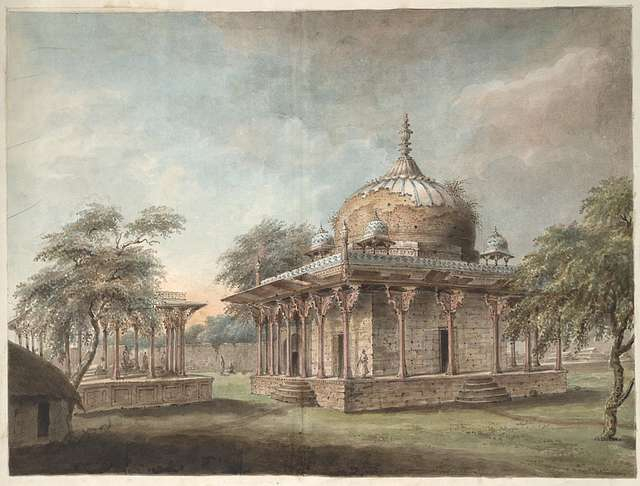

Painting of Nadan Mahal, 1814. (Picture Credits: British Library/Wikimedia Commons)

The early foundations are represented through Mughal-era architectural remains such as Nadan Mahal, featuring characteristic elements such as domed mausoleums, arched entrances, octagonal turrets and intricate stucco ornamentation. However, Lucknow’s transformation into a major architectural centre occurred in 1775 when Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula shifted the capital of Awadh from Faizabad to Lucknow. This move attracted master architects, artisans and poets, many of whom had migrated from Delhi following the Mughal decline, leading to the rise of a distinct Awadhi architectural identity.

Nawabi Architecture: A Distinctive Blend of Styles

The Nawabs of Awadh visualised an architectural style that brought together Mughal grandeur with Persian, Turkish and European influences.

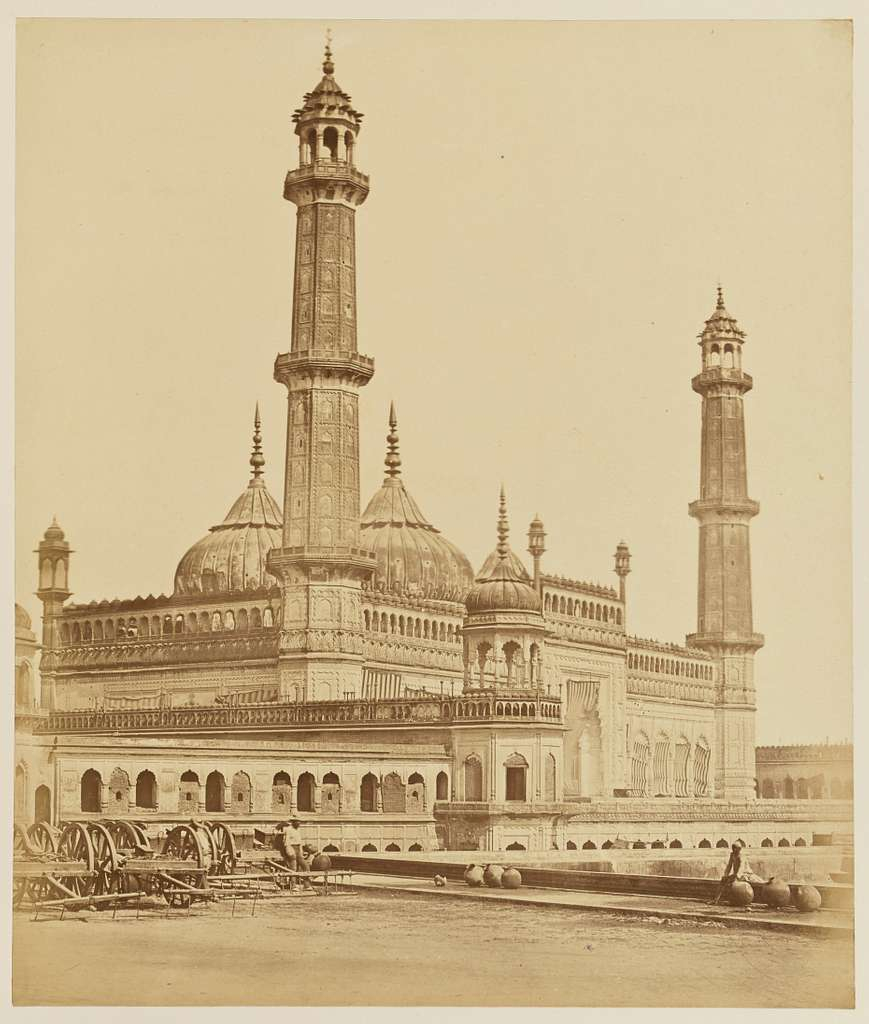

Southwest view of the Bara Imambara, 1858. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

The Bhool Bhulaiya, a labyrinth of interconnected passages, designed above the Imambara hall. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Asafi Mosque. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Bara Imambara Complex. (Picture Credits: Meenakshi Vashisth)

The Asafi Mosque, with its grand domes, carved arches, and soaring minarets. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

View of Asafi Mosque featuring three domes, two minarets, chhatris and ornate stucco work with floral motifs. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

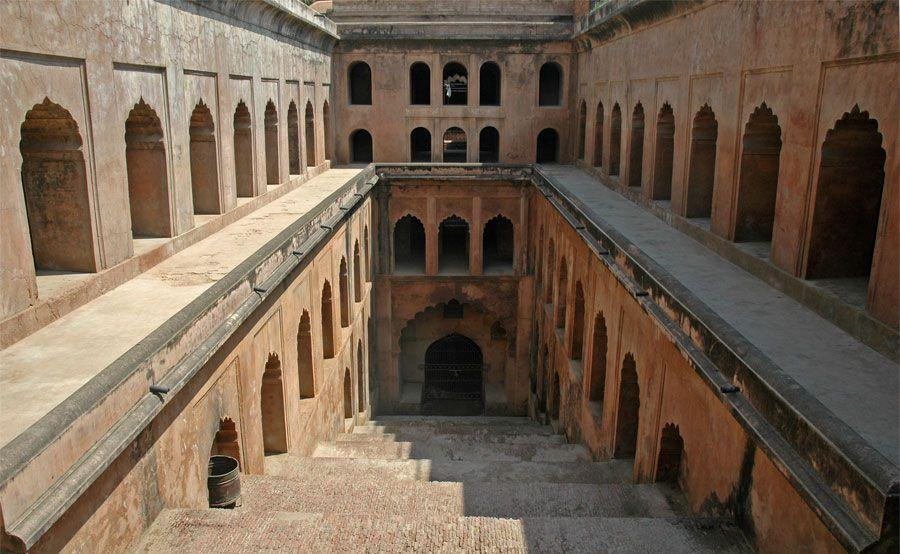

One of the most prominent architectural legacies of the Nawabs is the Bara Imambara. Commissioned by Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula in 1784, the Bara Imambara was designed by architect Kifayat Ullah. Initiated as a relief project, its construction generated employment for thousands afflicted by a famine. The structure is famed for its Bhool Bhulaiya, a labyrinth of over 1,000 interconnected passages designed to confuse intruders. Constructed using lakhori bricks and surkhi-chuna (mortar and lime), the Imambara was reinforced with organic materials such as jaggery, lentils and bel pulp to ensure durability. The acoustics of the complex allow even a whisper in one hall to be heard in another. The site also houses the Asafi Mosque, with its grand domes, intricately carved arches, towering minarets and stairways leading to the upper levels. The Shahi Baoli, within the complex, a five-storey stepwell, still holds water, though only the top two storeys are visible today.

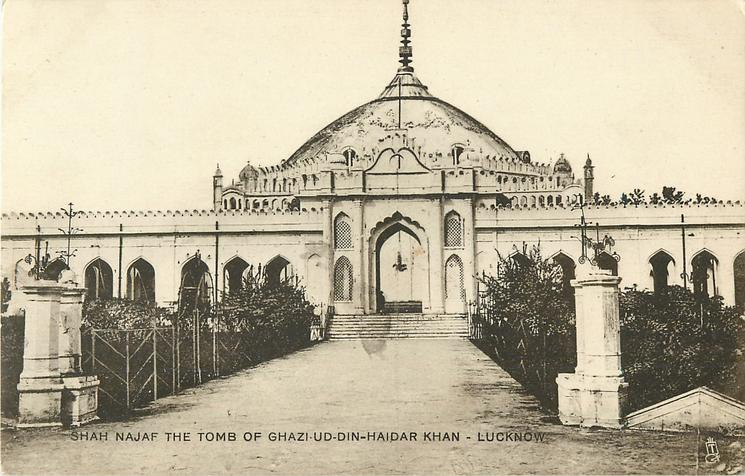

Other prominent imambaras in Lucknow include the Chota Imambara (1837), built by Nawab Mohammad Ali Shah, known for its stunning chandeliers and calligraphic panels, and the Shah Najaf Imambara (1814), which houses the tomb of Nawab Ghazi-ud-Din Haider. These structures, along with Talkatora Imambara (1818), reflect the deeply embedded Shia traditions of Awadh.

Shahi Baoli in the Bara Imambara complex. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Chota Imambara. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Wall of Chota Imambara adorned with delicate stucco engravings of intricate floral and geometric patterns. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Shah Najaf Imambara. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

As the Nawabs of Awadh developed their distinct architectural style, they diverged from the Mughal tradition of using red sandstone and marble, instead relying predominantly on plaster. The preference for lime plaster and lakhori bricks, which were more accessible and cost-effective, not only reflects the fiscal realities of the Nawabi state but also underscores the adaptive nature of their architectural practices in response to local material resources.

In addition to these grand imambaras, the Nawabs and aristocrats built azakhanas, or private mourning houses, for instance the Shahi Azakhana, Karbala Rafiq-ud-Daula (Karbala Abbas Bagh) and Rauza of Ali Ibn Muhammad, where majlis gatherings with recitations of marsiyas and nohas were held. Many of these intimate spaces still exist within noble households, preserving the Shia cultural heritage of Awadh.

A watercolor painting of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula at a Muharram observance in the Imambara, 1795. Part of the Hyde collection. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Rumi Darwaza. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Beyond religious structures, Asaf-ud-Daula’s architectural vision extended to his Daulat Khana complex, covering 45 acres. This estate housed several important buildings, including Mehtab Bagh, a pleasure garden later repurposed as a British parade ground. The Rumi Darwaza (1784), an imposing gateway inspired by the Sublime Porte in Istanbul showcases Awadhi architecture infused with strong Mughal and Turkish influences. Rising to a height of nearly 60 feet, the structure features an intricately carved central arch adorned with floral motifs, delicate stucco ornamentation and ornate cornices. The gateway is flanked by minaret-like structures and crowned with a beautifully sculpted chhatri. The recessed niches and arched windows add depth and elegance, while the lack of wood or iron in its construction highlights the brilliance of Lucknow’s architectural craftsmanship.

Another significant palace complex was Chattar Manzil (1780s–1830s), the primary royal residence. This Indo-European structure is distinguished by its gilded chhatris, arched verandas, deep colonnades and underground cooling chambers.

Qaiserbagh, commissioned by Nawab Wajid Ali Shah in 1847, was the last grand palace complex of the Nawabs of Awadh. Designed as an opulent paradise, it featured magnificent structures such as Chaulakhi Kothi, Chandiwali Baradari and Naginewali Baradari, set amidst landscaped courtyards and lush gardens. The Lakhi Darwaza, or ‘Gateway of a Hundred Thousand’, adorned with gilded details and intricate stucco embellishments, served as a regal entrance. The palace’s delicate plasterwork, ornate lattice screens and domed pavilions reflected a fusion of Mughal, European and Awadhi architectural styles. A defining feature of Qaiserbagh was the Mahi Maratib, or fish insignia, symbolising prosperity and divine favour, prominently displayed on archways and gateways to reinforce Lucknow’s royal identity. Designed for both courtly pleasures and royal administration, the complex was structured around symmetrical courtyards, with arched colonnades, intricately carved jharokhas, and miniature domes and finials adorning the rooftops. Its plasterwork, floral patterns and Persian-style calligraphy mirrored the finesse of Lucknow’s famed zardozi embroidery.

View of Qaiser Pasand Palace in the Qaisarbagh complex, 1863-1887. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

Lakhi Darwaza gateway with the Mahi Maratib, or fish insignia. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

The Lakhi Darwaza, also known as ‘Gateway of a Hundred Thousand,’ with its gilded details and intricate stucco, 1858. (Picture Credits: GetArchive)

Sikandar Bagh. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Details of the gate in Sikandar Bagh. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

British traveller George Russell described Qaiserbagh as a ‘bewildering maze of palaces and gardens, fit for the indulgence of an Eastern prince,’ while Lord Dalhousie dismissed it as ‘a monument of extravagance,’ reflecting British disdain for Nawabi opulence. French writer Louis Rousselet, however, admired its ‘delicate ornamentation and dreamlike beauty,’ calling it one of India’s most remarkable palace complexes. Qaiserbagh suffered extensive damage after 1857, when the British partially demolished sections in retribution. However, significant portions, including the Safed Baradari and several gateways, have survived.

Apart from Qaiserbagh, the Nawabs cultivated several gardens that reflected their love for leisure and aesthetics, shaping Lucknow into a gulistan (garden city). Many, like Charbagh, Aminabad, Aishbagh and Musa Bagh, lent their names to entire neighbourhoods. Musa Bagh, a riverside retreat, featured sprawling lawns and an elegant baradari, while Aishbagh was designed as a paradise-like escape. Sikandar Bagh, commissioned by Wajid Ali Shah, was a walled pleasure garden with arched gateways and intricate stucco work. It later became a key battleground during the Revolt of 1857.

European Influences

By the late eighteenth century, European architectural elements had begun to make a debut in Lucknow’s built environment. The British and French, who initially arrived as traders and soldiers, gradually established fortified residency complexes and expansive villa-style kothis, reshaping the city’s architectural vocabulary. One of the best examples is the Dilkusha Palace (1800), designed by Gore Ouseley for Nawab Saadat Ali Khan. Modelled after Seaton Delaval Hall in Northumberland, it features tall Corinthian pillars, arched verandas, Gothic-style battlements and decorative balustrades. Originally built as a hunting lodge, it was later repurposed as a British military residence.

Dilkusha Kothi. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Dilkusha Kothi. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Dilkusha Kothi. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

The Residency remains. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Made of lakhori bricks, this building in the Residency complex once housed Captain and Mrs Routleff. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

The Residency remains. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Dr John Fayrer’s House in Residency, where he provided medical aid during the siege. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Built in 1775, under the patronage of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula, to house the British Resident, the Residency was a fortified enclave and later became the residence of the chief commissioner of Awadh. The complex gained historical significance during 1857, when it endured an 87-day siege led by Indian rebels against the British forces commanded by Sir Henry Lawrence, who succumbed to injuries during the attack. The Residency remains a poignant memorial to the first fight against the British, with its ruins still bearing cannon fire scars. Architecturally, the Residency blends Gothic and neo-classical styles, featuring thick brick walls, pointed arches, symmetrical layouts and defensive bastions that highlight its military function. The complex comprised several key structures—including the Banqueting Hall, once used for grand receptions, now reduced to skeletal remains; Dr Fayrer’s House, where Dr John Fayrer provided medical aid during the siege; a heavily fortified treasury; the church and cemetery, where Sir Henry Lawrence and other British officials were laid to rest; and the Bailey Guard Gate, named after Major John Baillie, which served as a critical defensive point. Today, the Residency serves as silent witnesses to one of the most defining uprisings of the colonial era.

During this period of architectural experimentation, Claude Martin (1735–1800), a French adventurer, architect and philanthropist serving under Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula, left an indelible mark on Lucknow’s built heritage. Blending European aesthetics with Indo-Islamic traditions, his most renowned creation is the Constantia building (now part of the La Martiniere College complex), named after his motto Labore et Constantia (By Labour and Constancy), which features Palladian symmetry, Gothic turrets, Rococo ornamentation and Indian elements like chhatris and jharokhas. Constantia influenced later structures like Khursheed Manzil, Shahnajaf Imambara and the Sher Darwaza of Qaiserbagh.

The Bailey Guard Gate, named after Major John Baillie, served as a key defensive point during the 1857 uprising. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

The Residency’s bullet-ridden walls and ruins. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Beyond Constantia, Martin’s influence extended to Farhat Baksh Kothi (compared to Chateau de Lyon in France) and Bibiapur Kothi, a riverside retreat for Nawabi durbars (courts). These structures introduced European villa aesthetics to Lucknow while integrating indigenous elements.

La Martiniere (1798), Martin’s residence and final resting place, is a remarkable study of fusion. The interiors boast ornate stucco work, vaulted ceilings and a blend of European frescoes with traditional Indian craftsmanship. Its basement, designed as a flood shelter with hidden chambers, reinforces its fortress-like character.

Major General Claude Martin, a French adventurer in British service, commissioned Constantia. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Constantia (now La Martiniere). (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

George's Medical University. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

St. Joseph’s Cathedral. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Christ Church. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Christ Church. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Following the 1857 Revolt, the British introduced public institutions such as the High Court, and the Secretariat, all designed in a style incorporating domes, colonnades and chhatris over distinctly British layouts. Institutions like Loreto Convent (1872), with its arched windows, high ceiling, and colonial-style corridors, stands as a fine example of this fusion. Isabella Thoburn College (1870) showcases a similar architectural synthesis with its elegant facades and decorative motifs, while Canning College (1864) (now part of Lucknow University) features domes, minarets and European-style columns. The King George's Medical University (1911) is another prominent structure, distinguished by its majestic domes and intricate detailing that reflect Indo-Saracenic influences.

Built to commemorate first lieutenant governor of the United Province, Geroge Couper, the Hussainabad Clock Tower (1887) features Victorian architectural elements such as pointed arches, spines and finials, ornate carvings, clock with roman numerals, red bricks and cast-iron elements on railings and balconies.

Lucknow’s architectural identity is also shaped by its commercial and administrative districts. Hazratganj, originally a Mughal-era ganj (market), was transformed into a British cantonment before evolving into the city’s premier shopping district. The colonial influence is evident in its uniform facades, arched walkways and Victorian-style lamp posts, reminiscent of the shopping arcades of Europe. The district’s neo-classical and Indo-Saracenic buildings, with ornate cornices, pilasters and stucco detailing, reflect a blend of British town planning and Nawabi aesthetics.

Conclusion

Notably, Lucknow is among the first Indian cities to have designated heritage zones, recognising the historical and cultural significance of the city’s architectural heritage. From the grandeur of Nawabi-era imambaras and palaces to European-inspired colonial edifices, the city’s built heritage reflects centuries of evolution and adaptive craftsmanship, with each structure embodying the spirit of its time.

Bibliography

Dwivedi, Sharada. Lucknow: The City of Illusion. Mumbai: Marg Publications, 1993.

Oldenburg, Veena Talwar. The Making of Colonial Lucknow, 1856-1947. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Srivastava, Harish Chandra. The Genesis and Development of Awadh Culture. Allahabad: Chugh Publications, 1979.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).