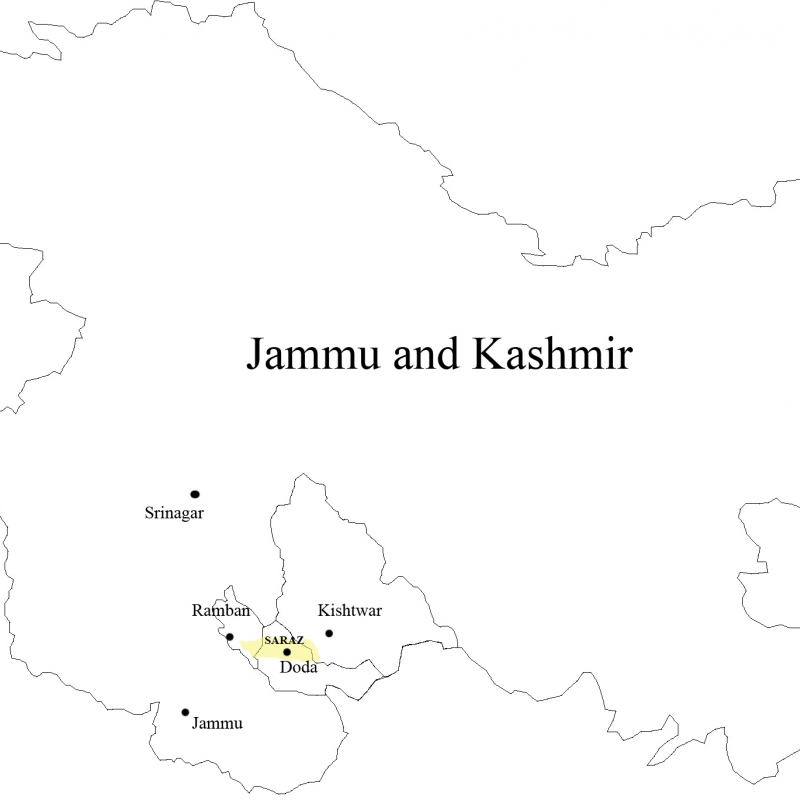

Saraz is a region in the Jammu division of Jammu and Kashmir state of India. The spelling (Romanː Siraj, Siraz, Saraj or Saraz; Devanagariː सिराज, सराज; Perso-Arabicː سراج. سراز) and pronunciation (IPA: sɪrɑːd͡ʒ, sɪrɑːd͡z ,sɪrɑːz, sərɑːd͡ʒ, sərɑːd͡z ,sərɑːz) varies within the region. It comprises the northern half of Doda and parts of Ramban and Kishtwar districts[1]. It is at the centre of Chenab Valley, a term often used to refer to the mountainous belt of north-eastern Jammu. The Chenab river flows through the centre of this mountainous belt and defines the southern and eastern limits of Siraz. The neighbouring regions in a clockwise order are Kishtwar, Bhalessa, Bhaderwah, Rudhar, Duggardes, Ramban and Pogal. Deswal which is situated between Kashmir, Kishtwar, Saraz and Pogal is variably excluded or included in the definition of Saraz. The extent of the region corresponds with the zone in which Sarazi language is spoken.

Various folk etymologies are available for the name of this region. The most widespread ones are derivatives of hundred kingdoms (So [Hundred] +Raj [Kingdom] = Soraj [Hundred kingdoms] à Siraj) and self-rule (Su [self] +Raj [rule] = Suraj [self-rule] à Siraj). The idea behind them is the belief that the area once had a hundred rulers ruling their own tiny territories without external interference. A less-subscribed to etymology is of three kingdoms (Seh (three in Persian) + Raj (kingdom) = Sehraj (Three kingdoms) à Siraj). Some people in western Siraj believe that there were only three kingdoms with capitals in Rajgarh, Kashtigarh and Doda. Grierson (1919) records another etymology which is no longer heard—Shiva’s kingdom (Shiv + Raj = Shivraj à Siraj). This is a supposed metaphor for the wild terrain of Siraj. This etymology rhymes and fits in as a series with the traditional divisions of Kashmir—Miraj/Maraz (Maya’s kingdom), Yamraj/Yamraz (Yama’s kingdom) and Kamraj/ Kamraz (Kama’s kingdom). There are two other regions with the name Siraj in Kullu and Shimla districts of Himachal Pradesh.

Sarazi and Kashmiri are the major languages of the region. While Sarazi is indigenous to the region, Kashmiri, which is also spoken in other regions of Chenab Valley, is a supposed import from Kashmir Valley. Watali, Gojri, Dogri and Hindi-Urdu[2] are the other languages spoken here. 2001 census records 46,302[3] speakers of Sarazi and 67,290[4] speakers of Kashmiri[5]. Sarazi speakers comprise 34 per cent of the region’s population.

The population of Saraz as recorded in 2011 census is 1,79,014[6]. Muslims comprise 51 per cent of the population and Hindus 49 per cent. About 90 per cent of the population is rural. The headquarter of Doda District, popularly known as Doda City is the only urban centre of the region. Hindus mostly speak Sarazi as a first language. Dogri is spoken by a migrant minority in Doda. The Muslim population is linguistically heterogeneous. They comprise Kashmiri, Gojri, Watali, and to a lesser extent, Sarazi speakers. Hindi-Urdu is spoken as a second language by majority of the people. It is also the first language of a minority in Doda City. Outside the city, Sarazi is used as a second language by a significant number of people.

The languages neighbouring the Sarazi zone are Kishtwari in the east, Bhalesi, Bhaderwahi, Rudhari and Dogri in the south and Pogli in the northwest. There are many other undocumented languages which are spoken in the Chenab Valley region. In 2014, Neelofer Wani compiled a list of 30 languages spoken in the region.[7]

Classification

Languages may seem similar either because they have been in contact for a long time or they are genetically related. There is a pattern to the kind of words a language can usually borrow. Across languages, words can be categorised into closed and open classes. The closed class of words includes among others, pronouns, case markers, adpositions, conjunctions, auxiliaries and quantifiers. Nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs constitute the open class of words which can be easily imported from other languages. Even among them, specific domains of the lexicon like parts of the body, words referring to basic actions, basic elements of nature, basic colours, numbers below ten, personal pronouns, etc., which constitute very basic words every language has, and which a child first acquires, are rarely borrowed. A list of such words was made by Morris Swadesh (1950).

Speakers generally opt to borrow religious, technical and cultural vocabulary (McMahon and McMahon 2005). This is an important criterion in diagnosing whether similarities or shared vocabulary between languages are a result of contact or genetic relatedness. Languages change over time and generate into different languages. Based on repeated and regular similarities of form and meaning (2005) in basic domains of the lexicon and words of the closed class, the route of language change and splitting can be reconstructed. Shared innovations in language change are used to group languages together into successive groups which together constitute a family. All languages of a family can be traced to a single ancestral and often reconstructed proto-language.

Creoles are languages which develop out of intensive contact between genetically unrelated or distantly-related languages. A simpler grammatical system, mixed features and typological similarity to other creoles characterise them. Many creoles which have been documented, developed in the last few centuries out of contact between colonisers and a colonised population. Their mixed character makes them unsuitable for strictly placing them in language family networks.

Languages of Saraz belong to the Indo-European family of languages which are spoken in Europe, Iran and South Asia. Most of the languages spoken in northern India and Pakistan belong to the Indo-Aryan sub-family. There are further divisions within this of which Dardic, Northern/Pahari, Punjabi and Rajasthani group of languages are relevant here. The Dardic group of languages are spoken in Jammu and Kashmir, northern Pakistan and pockets in eastern Afghanistan. Kashmiri and Sarazi’s neighbours Poguli and Kishtwari belong to this group.

The Pahari group of languages are spoken across the middle and lower Himalayan belt stretching from Sikkim in the east through Nepal, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh to Jammu division of Jammu and Kashmir in the west. Western Pahari is a further subdivision whose languages are spoken in Jammu, Himachal Pradesh and Jaunsar-Bawar tract of Uttarakhand. Sarazi’s southern neighbours Bhaderwahi, Bhalesi, Khashali, Rudhari and Gaddyali, the language of migrant Gaddis belong to this group. Many shared features with Dardic differentiates Western Pahari languages from the Central Pahari (Garhwali, Kumaoni) and Eastern Pahari languages (Nepali).

The Pahari group of languages, though not physically contiguous, is closely related to the Rajasthani group of languages. Gojri is classified as a part of this group though it could well be a Punjabi-Rajasthani creole. The Punjabi group of languages are spoken in Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu division and most provinces of Pakistan. Dogri and its variants which are spoken in Saraz belong to this group. Watali is an undocumented language spoken by the Muslim community of Watals. Its genetic affiliation is hence unknown.

Sarazi cannot be easily slotted into a group as it shares features in different domains of grammar with all the above groups. Going by most of the arguments and evidences presented so far (Kaul 1977; Kogan 2012), Sarazi should be classed as a Western Pahari language. It would still make a very aberrant member of the group. Bailey (1908), who first documented Sarazi, classified it the same way.

Grierson (1919) who gave a more detailed sketch of the language in Linguistic Survey of India (1903-1928), classified it as a dialect of Kashmiri admitting that it could equally be classified as a Western Pahari language. Census of India archaically follows Grierson’s classification and considers it to be a dialect of Kashmiri. It subsumes the figures for Sarazi under the figures for Kashmiri while publishing final tables.

Among all the neighbouring languages, Sarazi shares the highest per cent of its vocabulary with Bhaderwahi. There, however, exist a few words of the closed class and syntactic features which are shared exclusively with its Dardic neighbours[8]. It’s less likely that these words were borrowed after contact with these languages. The Western Pahari-Dardic creole conjecture noted by Schmidt and Kaul (2008) for Sirazi has a wide scope for investigation.

There are no known historical records, archaeological evidence or studies in genetics to be able to construct a history of population movements in this region. The oral history of the region is obsessed with migrations. Kashmiri-speaking Muslims believe that they migrated from Maraz (Southern Kashmir) in different waves in times of natural calamities and starvation. The Hindus, especially Rajputs, believe that they migrated from Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Bengal and Jammu among other places to escape ‘Muslim rule’. A few communities like Megh do not subscribe to such beliefs and are considered by others to be indigenous to the region. Shared place and caste names, belief systems and customs lend plausibility to these beliefs. It should be noted that genetic relatedness of languages and genetic affinity or difference between speakers of different language communities cannot be corrated.

Structure

While most of the grammatical features of Sarazi are shared with Western Pahari languages, some of them are shared exclusively with Dardic languages. In this section I will discuss a few prominent features of Sarazi’s grammatical structure.

Phonology

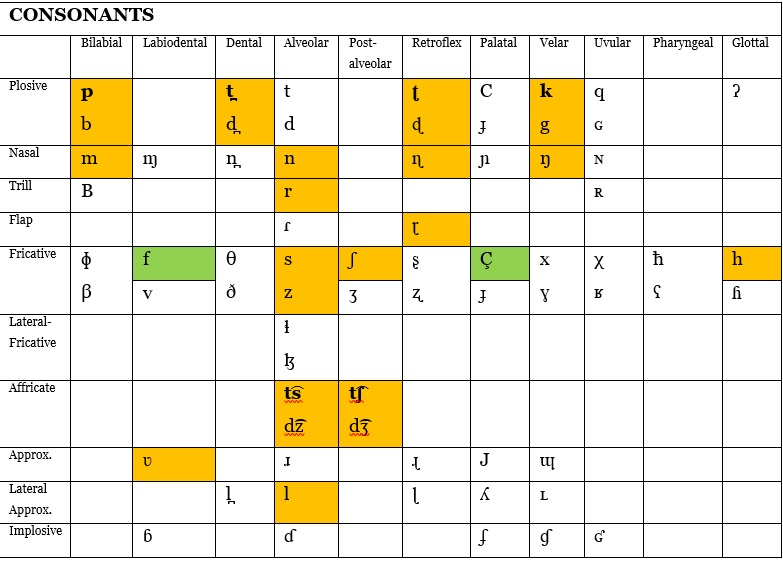

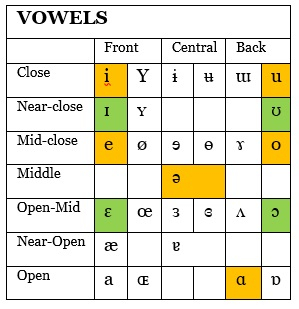

The International Phonetic Alphabet is to speech phonetics what a periodic table is to chemistry. The IPA tables below represent all the possible consonant and vowel sounds in human language. Consonants are classified based on manner and place of production of a sound and vowels are classified based on height of the mouth-opening, position of tongue in the mouth and lip-shape. One can refer to many interactive IPA charts available on the internet to make sense of the sounds.

The blank cells represent sounds which have never been attested in any language. The inventory of sounds in any language are made up from sounds in this table. The coloured cells represent Sarazi’s inventory of sounds.

Table 1ː IPA Consonants

Table 2ː IPA Vowels

The cells highlighted in yellow represent the ‘phonemes’ of Sarazi and the cells highlighted in green represent ‘allophone'. Phonemes are distinct sounds perceived in a language and allophones are various sounds which are perceived as variants of a single phoneme.

In cells with two symbols, the upper and lower ones are voiceless and voiced counterparts of the same sound. A sound becomes voiced when there is simultaneous buzzing produced by the vocal folds. Thus, when ‘p’ is accompanied by a buzz from the vocal folds, it becomes ‘b’. A sound is aspirated when it is accompanied by a puff of air. Thus, the first sound in ‘pʰɑl’ (fruit) is the aspirated version of same in ‘pɑl’ (moment).

Sarazi only aspirates voiceless sounds, voiced sounds are not aspirated in Sarazi. Voiced aspirates are a trademark of Indo-Aryan languages and are not found elsewhere in the world. Where other Indo-Aryan languages have a voiced aspirate, Sarazi has a high tone. The equivalent of Hindi-Urdu bhɑr (fill) is bɑ́r. The sign above the vowel ‘ɑ’ represents a high tone. Where Hindi-Urdu aspirates b, Sarazi instead produces it with a high tone. Voiced aspirates are absent in Dardic languages, Kashmiri, Dogri, Hindko, Punjabi, Haryanvi and many Western Pahari and Rajasthani languages. While Kashmiri does nothing to compensate the absence of aspiration, others compensate with a high tone or a low tone.

The sounds ‘t͡s’ and ‘d͡z’ of Sarazi are also found in Kashmiri as well as other Pahari languages in the neighbourhood, but not in Dogri, Gojri and Hindi-Urdu. Kashmiri has an elaborate system of vowels which is absent in Sarazi. The sound system of Sarazi is typically Western Pahari.

Morphology and syntax

Personal Pronouns

Words may refer to entities in the world, actions, events, attributes, concepts, etc. Pro-forms refer to previously uttered words or phrases and are used to substitute them. Personal pronouns are used to refer to participants in a discourse and other people. Tables 3 and 4 represent the paradigm of personal (and demonstrative) pronouns in Sarazi.

Table 3ː Sarazi Personal Pronouns - 1

|

Person |

Singular |

Plural |

|

I |

ɑ̃ːw |

ɑː |

|

II |

t̪u |

t̪uː |

Table 4ː Sarazai Personal/Demonstrative Pronouns

|

Person |

Masculine Singular |

Masculine Plural |

Feminine Singular |

Feminine Plural |

|

III-1 |

ɛŋ |

ɛɽ̃ |

ɛŋ |

ɛɽ̃ə |

|

III-2 |

ʊŋ |

ʊɽ̃ |

ʊŋ |

ʊɽ̃ə |

|

III-3 |

t̪ɛŋ |

t̪ɛɽ̃ |

t̪ɛŋ |

t̪ɛɽ̃ə |

Compare the above with the paradigm of pronouns in Dogri.

Table 5ː Dogri Personal Pronouns

|

Person |

Singular |

Plural |

|

I |

ɑ̃ːw/mẽ |

ɑs |

|

II |

t̪ũː |

t̪ʊs |

|

III-1 |

é |

é |

|

III-2 |

ó |

ó |

What makes Sarazi different from popular Indo-Aryan languages—Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi, Bengali and Marathi—is that other than number and gender, three degrees of distance are distinguished in demonstrative pronouns. The first row of pronouns in the second table for Sarazi is used to refer to a person or entity which is located close to the speaker. The second row refers to person or entity not close to the speaker but within a visible distance. The third refers to a person or entity out of sight of the speaker. This many distinctions in distance/visibility are also made in Kashmiri and a few Pahari languages.

Distinction in gender in the third person is made in many other Indo-Aryan languages. Thus, while the third person pronoun is invariant in Hindi-Urdu (1a-je), it varies with gender in Sarazi (1b-ɛɽ̃ for masculine and ɛɽ̃ə for feminine).

- These boys and these girls

- je ləɽke ɔr je ləɽkɪjɑ̃ (Hindi)

- ɛɽ̃ mɑʈʈʰe d̪e ɛɽ̃ə rẽt̪ijɑː (Sarazi)

इण मट्ठे दे इणअ रेंटिया اینڑ متٹھے دے اینڑ` رینتیا

Auxiliary

Auxiliaries are words which occur adjacent to the verb. Among others, they do the job of locating the event or state expressed by the verb in time, i.e., tense. In the present tense, auxiliaries in Indo-Aryan languages generally vary according to the person or number of the subject. Table 6 is a paradigm of Hindi-Urdu present tense auxiliaries.

Table 6ː Hindi-Urdu Auxiliaries

|

Person |

Singular |

Plural |

|

I |

hũ |

hɛ̃ |

|

II |

hɛ |

hɛ̃ |

|

III |

hɛ |

hɛ̃ |

Thus, the same auxiliary can’t be used for different persons and numbers. ( 2-4) show that in Hindi-Urdu, the first person singular auxiliary is different from first person plural (5) and second person singular auxiliary (6). The symbol ‘*’ indicates that a sentence is ungrammatical.

- I work

- ɛ̃ kɑm kərt̪ɑ hũ

- We work

- *həm kɑm kərt̪e hũ

- həm kɑm kərt̪e hɛ̃

- You work

- *t̪u kɑm kərt̪ɑ hũ

- t̪u kɑm kərt̪ɑ hɛ

In Sarazi, present tense auxiliaries vary on a third dimension—gender. All the combinations of person, number and gender add up to 12 forms. Table 7 is a paradigm of present tense auxiliaries in Sirazi.

Table 7ː Sarazi Auxiliaries

|

Person |

Male Singular |

Male Plural |

Female Singular |

Female Plural |

|

I |

cʰe |

cʰɑm |

cʰɑ̃ |

cʰɑmɑː |

|

II |

cʰe |

cʰɑt̪ʰ |

cʰɑː |

cʰɑt̪ʰiː |

|

III |

cʰo |

cʰe |

cʰi |

cʰijɑː |

Compare the above with the paradigm of present tense auxiliaries in Kashmiri which also vary on three dimensions. Also note that the auxiliaries in both languages share similar forms.

Table 8ː Kashmiri Auxiliaries

|

Person |

Male Singular |

Male Plural |

Female Singular |

Female Plural |

|

I |

cʰus |

cʰi |

cʰɑs |

cʰɑ |

|

II |

cʰukʰ |

cʰiv |

cʰakʰ |

cʰɑvɨ |

|

III |

cʰu |

cʰi |

cʰi |

cʰɑ |

Thus where (2) above in Hindi-Urdu represents the speech of a person of any gender, it will generate two translations in Sarazi based on the gender of the speaker.

- I work (Male): ɑ̃w kɑm kerɑ̃ː cʰe

- आँव कम केरां छे آں و کم کراں چھے

- I work (Female): ɑ̃w kɑm kerɑ̃ː cʰɑ̃

- आँव कम केरां छा آں و کم کراں چھا

Among the neighbouring languages, Sarazi shares the features of auxiliaries exclusively with Kashmiri, Poguli and Kishtwari. Auxiliaries in Bhaderwahi (Dwivedi 2013), Dogri and Gojri (Sharma 1982) are different in form and like Hindi-Urdu, vary only on two dimensions—person and number.

Table 9ː Bhaderwahi Auxiliaries

|

|

Singular |

Plural |

|

I |

ɑĩ |

əm |

|

II |

əs |

ət̪ʰ |

|

III |

ɑe |

ɑn |

Table 10ː Dogri Auxiliaries

|

|

Singular |

Plural |

|

I |

ɑ̃ː |

ɑ̃ː |

|

II |

ẽ |

o |

|

III |

æ |

nə |

Table 11ː Gojri Auxiliaries

|

|

Singular |

Plural |

|

I |

ũ̀ː/ ɑ̃̀ː |

ɑ̃̀ː |

|

II |

ɛ̀ |

ẽ̀ |

|

III |

ɛ̀ |

ẽ̀ |

Passive verb

Passivisation is a grammatical operation in which the object of a sentence is made the subject and the original subject is deleted or made optional. To make this possible either the form of the verb is changed, or another verb is placed next to the verb. English and most Indo-Aryan languages use the latter strategy; Sarazi opts for the former.

(8) is the passive version of (7). In (7), the first-person pronoun (I/miː/mɛ) is the subject and Ram is the object. In (9), Ram is made the subject and the original subject is optional and thus does not have to appear in the sentence. In English, the third person singular past tense auxiliaries ‘had’ and ‘been’ are placed before the verb. In Hindi, a verb gəjɑ—in the third person singular past participle form—is placed next to the verb (7a and 8a). Sarazi uses a different strategy. An affix ‘-v’ is inserted into the verb mɑːro (7b and 8b)

- I killed Ram

- miː rɑːme mɑːro मी रामे मारो می رامے مارو

- mɛ̃ ne rɑːm ko mɑrɑ (Hindi-Urdu)

- Ram had been killed

- o रा rɑːm mɑːrvo राम मार्वो رام ماروو

- rɑm mɑrɑ gəjɑ (Hindi-Urdu)

This strategy of forming passives is found in Sindhi, Siraiki and Rajasthani languages in South Asia.

Past perfect

In most Indo-Aryan languages the past perfect is expressed by a past particple form of the verb followed by a past tense auxiliary. The formula is thus: Past Perfect= Verb (past participle form) + Past Auxiliary

The third person singular past participle form of Hindi-Urdu verb d͡ʒɑ (go) is gəjɑ and the third person singular past tense auxiliary is t̪ʰɑ. Thus the past perfect form of the sentence (9) is (10).

- He went to Doda

- vo ɖoɖɑ gəjɑ

- He had gone to Doda

- vo ɖoɖɑ gəjɑ t̪ʰɑ

The Sarazi third person singular auxiliary is bút̪o and third person singular past participle form of the verb ‘gɑː (go)’ is geo. Following the general formula of Indo-Aryan languages, the past perfect form of the sentence (11a) should be (12b). But (12b) is ungrammatical. The past perfect is rather expressed by a suffix ‘–ro’ on the verb (12a).

- He went to Doda

- t̪eŋ ɖoɖe geo

तेंग डोडे गेओ تینگ ڈوڈے گیو

- He had gone to Doda

- t̪eŋ ɖoɖe guro

तेंग डोडे गूरो تینگ ڈوڈے گورو

- *t̪eŋ ɖoɖe geo buːt̪o

तेंग डोडे गेओ भूतो تینگ ڈوڈے گیوبھوتو

This method of expressing past perfect is also used in Pahari and Rajasthani languages.

Pronominal suffix

In (13-14), there are two Sarazi translations (a) and (b) for a single English sentence. (a) and (b) differ in the number of elements in the sentence with the latter being shorter. (a) sentences have pronouns(s) in the beginning and a verb or auxiliary at the end. In (b), the pronouns are absent. Instead, they are represented by elements which are a part of the verb (e.g., ‘mi’ represents ‘ɑ̃w’ and ‘t̪’ represents ‘t̪u’ in 13b). Thus, two pronouns and a verb, i.e., three words are represented by a single word. The elements which represent the pronouns are known as pronominal suffixes.

- I am giving you advice

-

ɑ̃w t̪u-ĩ sɑlɑː d̪ei rɑw che

आँव तूई सला देई रव छे آں و تویں سلا دیئی رؤ چھے - sɑlɑː d̪ei rɑw chɑmɪt̪

सला देई रव छमित سلا دیئی رؤ چھمت

- You are giving me advice

- t̪uː miː sɑlɑː d̪ei rɑw che

तू मी सला देई रव छे تومی سلا دیئی رؤ چھے

- sɑlɑː d̪ei rɑw chɑsɪm

सला देई रव छसिम تو می سلا دیئی رؤ چھسم

Though pronominal suffixes/clitics are a feature of many languages of the world, it is not a general feature of the languages of South Asia. Sarazi shares this feature only with its Dardic neighbours and none of the southern neighbours—Bhaderwahi or Dogri. This feature was the sole reason Grierson (1919) classified Sarazi as a variety of Kashmiri. Pronominal suffixes have also been attested in Sindhi, Saraiki and a few varieties of Punjabi.

When the pronoun must be emphasised or focused upon, one strategy is to have both the pronoun and verb with pronominal suffixes in the sentence. (15a) and (15b) are Kashmiri and Sarazi versions of such a sentence in which the pronouns are emphasised.

- I give you medicine

- miː t̪u:ĩ sɑlɑː d̪emɪt̪

मी तूईं सला देमित آں و تویں سلا دےمت

- bɨ d̪ɪmɑj t͡se sɑlɑː

Note that the form of pronominal suffixes in Kashmiri and Sarazi are similar (‘m’ in d̪emɪt̪ and d̪ɪmɑj). Pronominal suffixes belong to the closed class of words and couldn’t have been simply borrowed because of contact between speakers of the two languages.

Language and the society

Most regions in South Asia are multilingual and Saraz is not an exception. Figures for the percentage of bilinguals in the region are not available[9]. In any case, Sarazi is not counted as a separate language by the Census of India and the figures for Watali are not published[10]. Most people possess various degrees of fluency in a language other than their mother tongue. Monolinguals seem to be confined to a section of illiterate rural women above the age of 40 and very old people of either gender. Even among them, a majority can comprehend Hindi-Urdu or Sarazi even if they aren’t able to speak them. Generally, Muslims are more multilingual than Hindus. Gojri speakers are less multilingual. Their language is intelligible to most people of Saraz.

Among the six languages spoken in the region, only Hindi-Urdu and Sarazi are not community specific. As mentioned previously, Muslims believe that they migrated from Kashmir during adverse circumstances. Kashmiri-speaking Muslims are of three categories:

- Kashmiri castes who have maintained their language after migrating to Saraz

- Kashmiri castes who switched to Sarazi after migrating to Saraz, but have been switching back to Kashmiri since a few generations.

- Local converts to Islam, who had or have been switching from Sarazi to Kashmiri since a few generations.

Sarazi is spoken as a second language by most rural Kashmiri speakers born before the millennium. Kashmiri is the second language of all Muslim Sarazi and Watali speakers. Most of them have been switching to Kashmiri since a few generations. Very few Hindus can speak in Kashmiri, though again, most of them can fully comprehend a conversation in Kashmiri. Doda City, has the highest number of Hindus who speak Kashmiri as a second language. Dogri is spoken as a second language by people who have spent a significant amount of time in Dogri speaking areas of Jammu either for education or because of temporary migration during militancy in the region. Watali is the only language which is not spoken as a second language by anyone.

Hindi-Urdu and Sarazi are lingua francas of the region. In the past two decades, Hindi-Urdu has encroached the space of Sarazi in this role and is almost replacing it. Hindi-Urdu also has the widest domain of use. It is the first language of many children, the language of trade, administration and education.

Homes in Saraz are largely monolingual spaces. Its usual for families to have matrimonial ties with people from areas neighbouring Saraz. Custom and power equations dictate that the wife moves to her husband’s home and learns his language. In exceptional cases, a neutral language—Hindi-Urdu—is adopted.

Speaking of Sarazi Hindus, the effort required to acquire Sarazi varies with the genetic distance of the wife’s language from Sarazi. Thus, Bhaderwahi, Bhalesi, Khashali or Rudhari-speaking wives generally don’t find it difficult to acquire Sarazi, but Kishtwari or Poguli-speaking wives need to put in some effort. Similarly, even if the wife speaks Sarazi, she must still acquire her husband’s dialect. This convergence is not tightly unidirectional. In many cases, the husband and children do end up acquiring passive knowledge of these languages through various opportunities of socialization with the woman’s family. Very few among them develop the ability to speak them fluently.

Things are a bit different for Muslims. Most Muslims of the neighbouring regions too speak Kashmiri. A Sarazi-speaking wife doesn’t usually have to newly learn Kashmiri, as all Sarazi-speaking Muslims generally know Kashmiri as a second language. As it is a trend among Sarazi-speaking Muslims to switch to Kashmiri, a Kashmiri-speaking wife moving into a Sarazi-speaking home doesn’t have to learn a new language. Instead, the husband adopts Kashmiri as the home language and the children acquire Kashmiri as a first language. Gojri and Watali speakers are strongly monolingual as they don’t intermarry with other Muslims.

Since the turn of the millennium, it has been a major trend among every language community to speak to kids in Hindi-Urdu. This trend sets Sarazi on a path to endangerment and is an alarm call for those interested in its sustenance.

In villages, immediate neighbours are usually from the same caste or religion who speak the same language. Social and economic networks of a locality, however, requires daily interaction with other language communities. Markets, schools, places of work and social gatherings set the stage for multilingualism. The following table represents the general trend in inter-community communication. The data for Watali is not presented. The first column represents the language of the speaker and the last row represents the language of the addressee. The cells in between represent the language(s) of communication between them. Languages are placed in the order of frequency of usage.

Table 12ː LANGUAGE USE BETWEEN COMMUNITIES

|

Sarazi |

Kashmiri |

Gojri |

Dogri |

Hindi-Urdu |

|

|

Hindi-Urdu

|

Hindi-Urdu Kashmiri |

Gojri Hindi-Urdu

|

Hindi-Urdu |

Hindi-Urdu |

Hindi-Urdu |

|

Sarazi Dogri

|

Hindi-Urdu Dogri |

Gojri |

Dogri |

Hindi-Urdu

|

Dogri |

|

Sarazi Dogri Gojri Hindi-Urdu |

Hindi-Urdu Kashmiri Gojri |

Gojri |

Dogri Gojri |

Hindi-Urdu |

Gojri |

|

Sarazi Hindi-Urdu Kashmiri

|

Kashmiri |

Gojri Hindi-Urdu Kashmiri |

Hindi-Urdu Kashmiri |

Hindi-Urdu |

Kashmiri |

|

Sarazi |

Sarazi Hindi-Urdu Kashmiri |

Gojri Hindi-Urdu Sarazi |

Sarazi Hindi-Urdu |

Hindi-Urdu

|

Sarazi |

It is not uncommon in Saraz for people of different language communities to have a conversation in which one addresses the other in a particular language to which the addressee responds in a different language and vice-versa.

Doda City , which also houses language communities from outside Saraz, is the market hub of Saraz. Hindi-Urdu is the language of the market. Hawkers go about their trade in Hindi-Urdu. Where readily recognisable, people from the same language community use their language—Sarazi, Kashmiri, Dogri or Bhaderwahi—in trade interaction. Hindu traders from other language communities can usually communicate in Sarazi when approached in that language. Sarazi and Kashmiri-speaking Muslim traders from the villages who have established businesses in the city can also communicate in Sarazi. Though, as far as city-born Muslim traders are concerned, only the very old among them can communicate in Sirazi. Kashmiri remains a language in which both city-born Hindu traders and Muslims, even from other language communities, can communicate comfortably.

Hindus use Sanskrit, Sirazi and Hindi-Urdu in religious rituals and Muslims use Arabic. Most Muslims can read the Quran in Arabic though a very few actually have a knowledge of the language. These are usually people who have received training in religious schools. Islamic canonical literature in Arabic is accessed through Urdu translations. Kashmiri and Urdu are the languages of religious sermons, religious instruction and devotional songs.

Though a large portion of Hindu canonical literature is in Sanskrit, it doesn’t have a status analogous to Arabic among Muslims. Few people learn Sanskrit. Religious literature is accessed through both Urdu and Hindi. Devotional songs are sung in many languages including Sarazi, Dogri, Chambeali, Punjabi and Hindi.

Urdu, English and Hindi are the languages of education. Primary education in most government-run schools is in Urdu. Hindi had been introduced as a medium of education in a few Hindu-dominated villages since the 1980s. Since the 2000s many schools have adopted English as the medium of education. English is also the medium of education in all private schools. Though the textbooks are in Urdu, Hindi or English, instruction is given in local languages—Sarazi or Kashmiri—at least at the primary level. Doda has a degree college which offers bachelors programmes in a limited number of disciplines. One usually goes to Bhaderwah, Jammu or Srinagar for specialisations or postgraduate study. Families which can afford it send their children to these places right from school. Many who temporarily migrate to Bhaderwah or Jammu for education, usually end up acquiring Bhaderwahi or Dogri as outside school and university, these languages are used in daily interactions. In the past migration to Jammu was the only option for university education. That’s the reason why more people used Dogri as a second language in the past.

Urdu and English are the languages of administration in the region. Courts, police stations and other government institutions maintain most of their records in Urdu. Many Hindus who haven’t learnt Urdu at school, end up learning it to be able to qualify for local government posts.

Internet is the most popular form of media. Facebook and YouTube are the commonly used apps. English being the dominant language of internet, people usually use Hindi-Urdu in Roman script (and rarely Sarazi or Kashmiri) while communicating over the internet or messaging on phone. Content on YouTube is accessed in Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi, English, Kashmiri and Arabic. Content in Sarazi is slowly sprouting up on Youtube as people are beginning to discover and learn about the democratic platform provided by internet. Hindi and Punjabi movies have the most viewers in Saraz. Television sets don’t have a ubiquitous presence in villages. Many listen to news broadcasts by state radio either on their phones or on radio sets. These news bulletins are in Urdu, Kashmiri and Dogri. Newspapers are read in Urdu and to a very limited extent in English or Hindi.

The role of religion in perception building

People’s perception about languages have no factual basis and are rooted in social beliefs. In Saraz, religion, among other usual factors, is a major determiner of attitudes people hold towards different languages. Muslims whose mother tongue is Sarazi are a minority in Saraz. Even among them there has been trend to switch to Kashmiri since a few generations. This is a part of a larger trend of Sarazi Muslims to identify with Muslims of Kashmir Valley culturally and historically.

Language is becoming a marker of religious boundary (Mahajan 2017). I have observed a few Muslims, referring to Sarazi as ‘Hindi’- (perceived as the language of Hindus) and a few Hindus referring to Kashmiri as ‘Musalmani’- the language of Muslims.

Not many outside the Chenab Valley region know about the existence of a language named Sarazi. Outside the state, Hindu-Sarazi speakers usually identify themselves as ‘Pahari’ when specifically asked about their linguistic affiliation. Linguistic links if any to Kashmiri are explicitly denied. Analogously, they identify culturally with neighbouring Himachal Pradesh. The speech of Muslims who speak Sarazi as a second language and Hindus who speak Kashmiri as a second language is perceived by the other communities to be less pure than what they speak. The diminishing role of Sarazi as a lingua-franca of the region is an implication of this splintered identification. A more neutral Hindi-Urdu is preferred.

The association of Urdu with Muslims, as is done in the rest of India, is less absolute in Saraz. Many use the names Hindi and Urdu synonymously. Though there are Hindu majority villages which have replaced Urdu with Hindi in schools and produced a generation illiterate in Urdu, the language’s value hasn’t diminished. Urdu in Perso-Arabic script is still the primary medium for many Hindus to access religious literature and a key to local government jobs. Hindi-Urdu in any case is accorded a higher status than their mother tongue by everyone in Saraz. Few old illiterate people don’t make distinction between Dogri and Hindi-Urdu. They perceive both as the same language of outsiders from the plains or rather as a language of power.

Having been in contact with Sarazi, the Kashmiri of Saraz has imported features from Sarazi at all levels of linguistic structure. This difference is explicitly perceivable by Kashmiri speakers of the Valley, who refer to this as ‘Gojri rather than Kashmiri’. This stems from the feelings of superiority, valley-dwellers have towards mountain-dwellers and the discrimination exhibited towards the Gujjar community who are given a low status in their world-view. Sarazi-Kashmiri speakers accept the lower status ascribed to their language. However, many residents of Doda feel their Kashmiri is less ‘Gojri’ in comparison to that of the villages.

Politics and economics of a ‘dialect’

‘Dialect’ is a term used in linguistics to refer to variations of a language. In this sense many dialects together make up a language. The society accords a prestigious status to one among them which then becomes the standard form of the language. Subsequently, the society perceives the standard to be the ‘language’ and others its ‘dialects’. In South Asia, it takes a distinct script and some literature to recognise any form of speech as a language or to upgrade status from a dialect to a language. The absence of a standard and ‘too many’ varieties of the language has prompted many to believe that Sarazi is a ‘dialect with no grammar’. This is one of the reasons for the discriminatory attitude of state in recognizing Sarazi.

Jammu and Kashmir’s constitution accords Urdu the status of the state’s official language and recognizes eight other regional languages—Kashmiri, Dogri, Ladakhi, Gojri, Pahari, Punjabi, ‘Dardi’ (Shina) and Balti—apart from Hindi for promotion. Shina and Balti have half the number of speakers of Sarazi. Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Arts, Cultures and Languages promotes and supports activities for developing only these languages. Unlike neighbouring Bhaderwahi which has fared better in having private organisations set up for such activities, Sarazi has none.

There is a tradition of folklore and writing poetry in Sarazi. There is no standard variety which a writer uses to write. One composes in his/her own dialect. Except for two collections of poetry by Bashir Ahmed Sirazi and Hari Singh, there is no published literature in Sarazi, though there are numerous unpublished manuscripts. The environment is not encouraging for Sarazi literature. (Refer to other articles in the module—Folk Songs of Saraz in Chenab Valley and Literature in the Sarazi Language —for more information)

Sarazi speakers are a minority within an economically backward Saraz. There is no political will or consolidation of any sort. Language is the least priority in a development-deprived area. Sarazi currently scores low in all the determinants of language vitality—social, economic and political power, demographics and institutional support.

Script

Urdu being the official language, Perso-Arabic is the most widely used script in Saraz. It is the default choice for writing Sarazi. Sarazi is rarely written and so are other languages like Kashmiri or Gojri. But the latter two have standardised orthographies which are used for writing in other parts of the state. Roman script is also as widespread as Perso-Arabic. Public signs like names of villages, business establishments, milestones, hoardings, posters and graffiti are in Perso-Arabic and Roman. Devanagari is making inroads since a few years. Names of a few Hindu majority villages and a few government and political campaign posters can be found in Devanagari. Before 1951, Dogri, which was one of the official languages of Jammu and Kashmir princely state, used to be written in Takri script. A few families have preserved documents and personal letters from those times which are in Takri script. Kitchen utensils and vessels manufactured in that era also tend to have the owner’s name engraved in that script.

Perso-Arabic is also used to write Punjabi in Pakistan and the Kashmiri language. These are modified versions of the script used for Urdu, with a few innovations to represent sounds which are not present or represented in Urdu. These innovations from Kashmiri and Punjabi are employed while writing Sarazi in this script. Kashmiri is also written in Devanagari script by a minority outside Jammu and Kashmir. When one chooses to write Sirazi in the Devanagari script, they adopt the same innovations used for Kashmiri Devanagari.

Neither Punjabi/Kashmiri Perso-Arabic nor Kashmiri Devanagari are sufficient to represent all sounds of Sarazi. What is missed in one script is present in the other and vice-versa. A few sounds have no unique representations. In that case, the symbol for the nearest sound is used (e.g., the symbol for z to represent both d͡z and z). Like all other languages of the world, Roman is a secondary script used to write the language.

|

Phoneme |

Perso-Arabic |

Devanagari |

Roman |

Example |

Meaning |

|||

|

ɽ̃/ɳ |

نڑ |

ण |

r,nn,nr |

pɑːɽ̃iː |

پانڑی |

पाणी |

paari paanri paanni |

water |

|

t͡s |

ژ |

च़ |

ts, ch |

kẽt͡s |

کینژ |

केंच़ |

kench kents |

someone |

|

t͡sʰ |

ژھ |

छ़ |

tsh,chh |

t͡sʰɑː |

ژھا |

छ़ा |

chhaa tshaa |

buttermilk |

|

d͡z |

ز |

झ़ |

jh, j, z |

d͡zul |

زل |

झ़ुल |

jhul,jul zul |

sleep |

Notes

[1] Ramban, Rajgarh, Kashtigarh, Bhagwah, Bharat-Bagla, Mohalla, Gundna and Drabshalla Tehsils.

[2] I use this term as structurally there is no difference between Hindi and Urdu. I refer to them separately only when Hindi in Devanagari script and Urdu in Perso-Arabic script are relevant to the discussion.

[3] The country level figures for Sarazi are double as two other languages with the name Siraji which are spoken in Himachal Pradesh, are mistakenly clubbed with the figures for this language and counted under Kashmiri.

[4] This is the number of speakers of Kashmiri in Doda tehsil. The southern half of this tehsil is situated outside Saraz. The number of Kashmiri speakers in Saraz region of Ramban and Kishtwar tehsils can’t be calculated as village level figures for mother-tongue are not available. The divisions are that of 2001 according to which Saraz constitutes three tehsils—Ramban, Doda and Kishtwar. The major portion of Saraz lies in Doda tehsil and hence I take Doda tehsil as the representative as whole of Saraz.

[5] The figures are for mother-tongue speakers and excludes those who speak Sarazi as a second-language.

[6] This has been calculated by adding up the population figures of Doda city, entire CD blocks Bhagwah and Gundna, 21 revenue villages of CD block Doda, 13 revenue villages of district Kishtwar district and 19 revenue villages of district Ramban- the constituents of Siraz.

[7] It needs to be checked if all the languages listed are structurally distinct from the neighbouring languages and unintelligible enough to their speakers to be be recognized as separate languages and not variants of the same. This list was probably compiled for Central Institute of Indian Languages. A few of these languages are currently being documented under the Scheme for Protection and Preservation of Endangered Languages (SPPEL).

[8] Dwivedi (2013) records 30 per cent lexical similarity with Bhaderwahi. Kogan (2012) noted that in Swadesh List, Siraji shares 48.4 per cent of the words with Dardic languages and 67.8 per cent of the words with the rest of the Indo-Aryan languages, i.e., Pahari, Punjabi, etc.

[9] Figures are available for a political division smaller than a state.

[10] Census does not publish figures for languages with less than 10,000 speakers.

References

Bailey, T. Graham. 1908. The Languages of the Northern Himalayas- Studies in the grammar of Twenty-Six Himalayan Dialects. Londonː The Royal Asiatic Society.

Dwivedi, Amitabh Vikram. 2013. A Grammar of Bhaderwahi. Languages of the World/Materials. Muenchenː Lincom Europa.

Grierson, George Abraham. 1919. Indo-Aryan Family (Northwestern Group). Linguistic Survey of India Vol.8 (Part 2). Delhiː Low Price Publications

Faridi, Farid Ahmed. 1993. Siraj- Ek Saqafati aur Lisani Jayza in Mohammad Ishaq Zargar (ed.) Zila Doda ki Adabi va Saqafati Tareekh. Dodaː Fareediya Bazm-e-Adab

Kaul, Priyatam Krishen. 1977. Chandrabhaga ki Tatvarti Parvatiya Boliyan (Siraji-Pogli-Padri).BhaderwahːHill-men’s Cultural Centre. Bhaderwah

Kogan, Anton. 2012. Once more on the so-called “mixed Kashmiri dialects”. Conference Presentation.10th International Conference of South Asian Languages and Literatures, Moscow, July 2012

Mahajan, Chakraverti. 2017. An Anthropological Study Exploring The Contours of Hindu-Muslim Relations in Bhagwah Village of District Doda, Jammu and Kashmir. Ph.D. Thesis. Punjab University, Chandigarh.

McMahon, April and Robet McMachon. 2005. Language Classification by Numbers. New York ːOxford University Press.

Schmidt, Ruth Laila and Kaul, Vijay Kumar. 2008. A comparative analysis of Shina and Kashmiri vocabularies. Acta Orientalia. Hermes Academic Publishing.

Sharma, Jagdish Chander. 1982. Gojri Grammar. CIIL Grammar Series-9. Mysoreː Central Institute of Indian Languages.

Swadesh, Morris. 1950. 'Salish Internal Relationships' in International Journal of American Linguistics, Vol. 16, 157-167