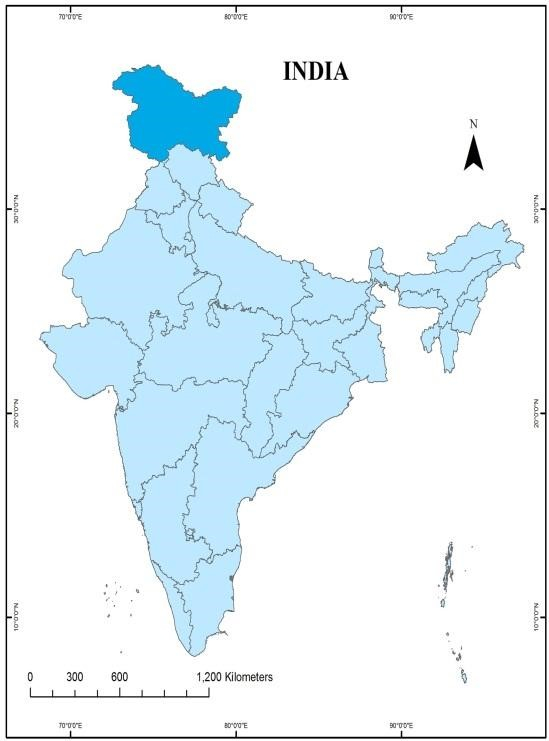

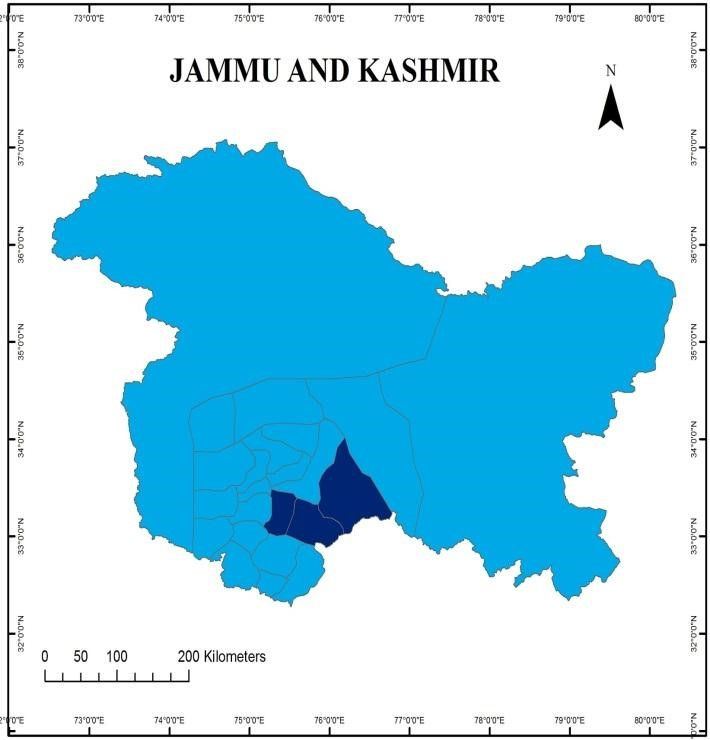

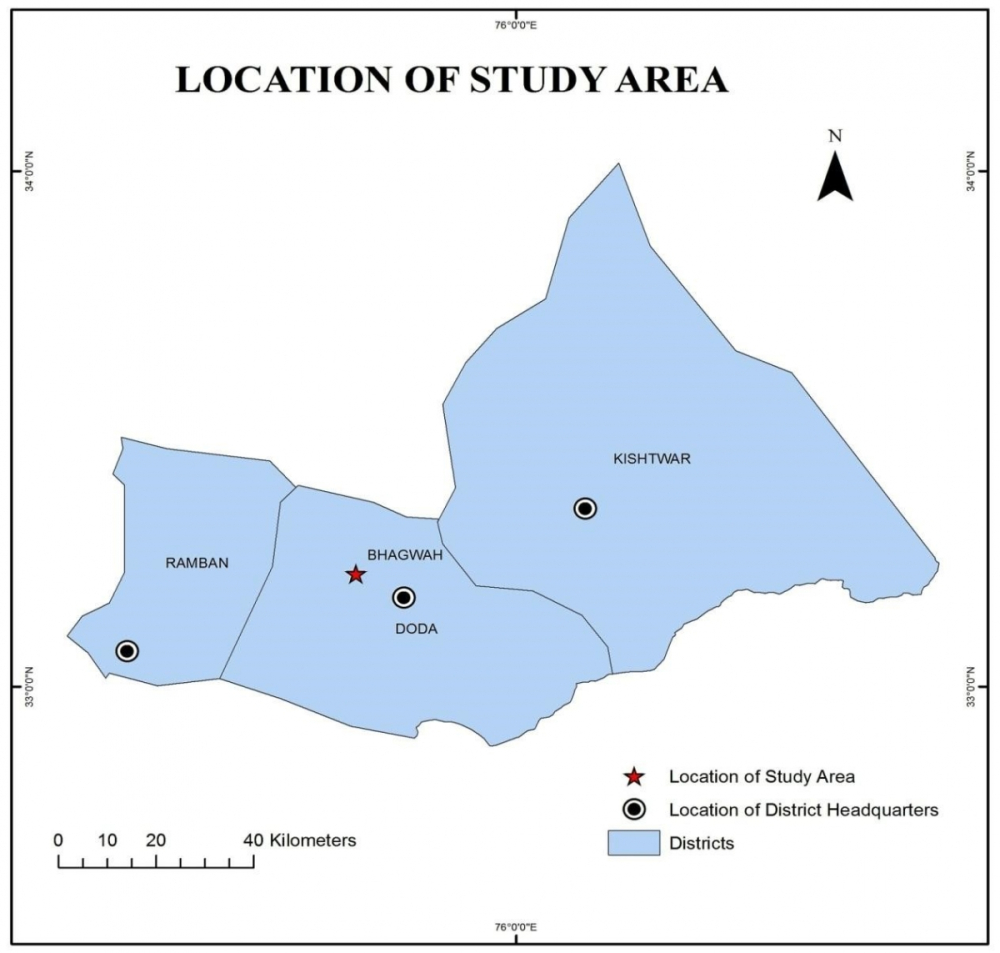

This essay introduces the linguistic zone of Saraz in the state of Jammu and Kashmir where Sarazi is the lingua franca of thousands of people. Saraz is located in the erstwhile Doda district, which was one of the six districts in Jammu province of the state before its territorial reorganisation in 2006. My association with the area goes back to 2006 when I started visiting this area to collect data for my doctoral dissertation (Mahajan 2017). My PhD thesis, in classical ethnographic manner, has mapped the impact of militancy on intercommunity relations in this subregion. The study was primarily carried out in a village called Bhagwah, located in Saraz. Most of my observations for this essay are based on my fieldwork in Bhagwah and its adjoining villages. In this essay, I have outlined geographical, historical, demographic and linguistic peculiarities of the Doda subregion in general and the Saraz linguistic zone in particular.

Doda

The erstwhile Doda or Doda subregion can be accessed by road, while driving north of Jammu, the winter capital of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. After an uphill drive of 170 kilometres on National Highway (NH) 44 (earlier referred to as NH 1), we reach the crest line of picturesque Dhauladhar (also Seoj Dhar) range of hills at the popular tourist resort of Patni Top. The state tourism department has constructed a number of alpine log huts to cater to tourists. The tall deodars at the ridgeline give way to orchards of apples and pears with tall trees of walnut and wild pomegranate as we move northwards and descend on the town of Batote.

In Batote, the national highway bifurcates. The main artery continues northwards down to Kashmir Valley through the towns of Banihal and Ramban after crossing the River Chenab in Chanderkot where the famous Baglihar Dam on Chenab is situated. From Batote, NH 244 (earlier 1B) takes off eastwards towards the town of Doda, which is the district headquarter of the erstwhile Doda District, and then onwards to Kishtwar. The road is cut through the steep hillsides on the southern bank of Chenab.

Also known as the fierce River Chandrabhaga in classical texts, the sources of Chenab are located in the glacial region of Pangi-Lahol. The upper course of the main river—after the two chief tributaries often known by the name Chandra Bhaga—separates the Great Himalayan Range and the Pir Panjal Range for a distance of some 250 km. Just above Kishtwar, the northern tributary Maru-Warwan joins the main river, which, at the same place, makes a sudden bend towards the south, penetrating the Pir Panjal. After another sudden bend towards the west at Thatri, it separates the Pir Panjal and the Dhauladhar as far as Arnas—a distance of 110 km. At this place, it is joined by the Ans Valley from the north. Along the extension of the Ans Valley towards the south, the Chenab penetrates the Dhauladhar Range and emerges from the hills near the town of Akhnoor. The river divides Doda subregion into two unequal halves.

The Doda subregion includes the districts of Doda, Kishtwar and Ramban. Earlier, the region was administratively a single unit and comprised one single district, namely, District Doda. However, in July 2006, there was a reorganisation of districts in Jammu and Kashmir and eight more districts were added. Doda district was trifurcated into three districts, namely, Doda, Ramban and Kishtwar. The subregion as a whole shares certain commonalities, which cannot be isolated for any one of the three districts which are a part of this area—in terms of geography, terrain, people, culture, politics and historical continuity.

Doda subregion is bound by Anantnag and Kargil districts in the north, Chamba in Himachal Pradesh in the southeast, Udhampur and Kathua in the south, and Rajouri and the Jammu region in the south-west. It is very significant from the point of view of geography. The subregion occupies a strategic place with its border touching all the three major provinces of the state.

The district derived its name from its district headquarter, Doda.[1] As per earlier records, the entire area of the erstwhile Doda District, including Tehsil Mahore, was initially divided into two independent states of Kishtwar and Bhaderwah. The history of Kishtwar dates back to 200 BC. Kishtwar was annexed to Jammu kingdom in 1821 AD but Gulab Singh, the ruler, did not visit Kishtwar. He appointed Mian Chand Singh as Amil (administrator) of Kishtwar and Zorawar Singh as governor of Kishtwar in June 1823.[2] In 1846, when the Dogra rule was established, the whole of Jammu and Kashmir situated to the east of River Indus and west of River Ravi, including Chamba and excluding Lahul, was handed over to Maharaja Gulab Singh. In 1875, the J&K state was divided into two divisions referred to as provinces, and Kishtwar was reduced to a district with Ramban as its tehsil. Kishtwar remained a district headquarter till 1909 before being placed under Udhampur Wazarat. The erstwhile Doda district was ultimately carved out in 1948 with Kishtwar as one of its tehsil (Zargar 2004).

The Doda subregion has an area of 11,691 sq. km. Before its trifurcation in 2006, it was one of the largest districts of the state. According to 2001 census, the region had a population of 6.90 lakh. Out of which 3,62,471 (52 per cent) were male and 3,28,003 (48 per cent) were female. Most of the population lives in villages. As per 2001 census data, the total rural population was 6,38,665. Out of this, 3,30,814 (52 per cent) were male and 3,07,851 (48 per cent) female. The total urban population was 51,809 of which 31,657 (61 per cent) were male and 20,152 (39 per cent) female. Overall sex ratio, according to 2001 census, was 901 female per thousand male. The urban ratio was as low as 637 female per thousand male as against 931 females per thousand males in the rural part. Out of the total population, 62,962 are scheduled caste and 79,751 are scheduled tribe. Thus, scheduled castes constitutes nearly 9 per cent of the total population and scheduled tribes form about 11 per cent of the total population.[3]

Doda’s population comprises different communities and though people follow different religions and speak different languages, they have an essential unity in their faith in a secular way of life. The secular outlook of the people is due to the fact that the population is a mixed one and is emotionally integrated (Rana 2016). Hindus and Muslims form a substantial part of the population; other communities like Sikhs, Buddhists and Christians also reside but in very small numbers.

Doda’s society therefore is a mixed one with Hindus and Muslims being two major communities. The population ratio between the Muslims and the Hindus in Doda region as per the census report of 2011 is around 60:40. Doda, Bhaderwah and Kishtwar are the three principal towns of the region. Muslims of Doda are mainly Kashmiri speakers and are ethnically closer to the Muslims of Kashmir. It will not be wrong to say that Doda’s Muslim society shares close social, cultural and political affinity with the Muslims of the Valley. Indeed, it is said that the Muslims of the region are migrants from the Valley who left Kashmir on various occasions due to the fear of being persecuted by tyrant rulers or due to natural calamities like famine and floods (Kotwal 2000).

Kashmiri, therefore, is one of the major languages spoken in the region. Other languages spoken in the area are Bhaderwahi, Kishtwari, Sarazi, Pogli, Padderi, Punjabi and Dogri. The Muslims of the area generally speak Kashmiri while Hindus use other languages—for instance, Sirazi in Doda, Kishtwari in Kishtwar, and Bhaderwahi in Bhaderwah. However, most of the people are well-versed with all the languages spoken in the area.

Table 1. Religion-wise data of Doda subregion as per 2011 census

|

District |

Total Population |

Hindu |

Muslim |

|

Doda |

409,936 |

187,621 (45.77%) |

220614 (53.82%) |

|

Kishtwar |

230,696 |

93931 (40.72%) |

133,225 (57.75%) |

|

Ramban |

283,713 |

81,026 (28.56%) |

200,516 (70.68%) |

Bhagwah and Saraz

Bhagwah owes its name to Raja Bhag Singh of Kishtwar, a 16th century ruler, who came to this part of his riyasat (chiefdom) to curb a rebellion. It is widely believed that Bhag Singh left some of his soldiers here to guard his territory. The 1890 Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak spells the name of Bhagwah as Bagu and notes that it is located between 33 degree north and 75 degree east, skipping details about its elevation. It further notes:

'Bhagwah lies in the valley above the left bank of the Lidar Khol stream, about 7 miles of Doda, on the path to Kashmir by the Brari Bal pass. It contains about forty-five houses, most of which are clustered in the village itself, the remainder being scattered in the fields around it; with one exception they are all single storied, built of mud in timber frames, with flat roofs; the double-storied house, which is the largest, is inhabited by the lambaddar, Suba, a son-in-law of wazir Labji. A Kashmiri Pandit resides in the village; the rest of the population are about equally divided between Hindus and Muhammadans. There is a considerable amount of cultivation about the village, which is well supplied with water from a rill which flows down through it from the hillside to the east; there is also a spring to the north. In the middle of the village, by the path just above it, is a fine chunar tree, beneath which is a takhtposh and a small Hindu temple; the usual camping ground close to this tree; it is very confined, but well shaded. Coolies and supplies are procurable.' (1890: 188)

Bhagwah village is situated at a distance of about 15 km from the district headquarter town of Doda in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Culturally, Bhagwah lies in an area known as Saraz. Saraz, traditionally, was a pargana of the erstwhile Kishtwar riyasat. The Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak (1890: 755) spells Saraz (also spelt as Siraj) as Siraz and describes it as ‘the district lying on the west side of the province of Kishtwar. It is drained by the Lidar Khol stream, and is traversed by the path leading from Doda to Brari Bal’. Ram Dhan’s assessment report (1912) includes this particular part in a zone called Kandi, literally meaning edge of the mountains. I interviewed Ram Singh (personal communication, 2011), a retired civil servant, during the course of my fieldwork, who described the geography of the area in these words:

'Saraj is a backward area (pasmanda ilaqa). Its topography is also very tough. Every child who is born in Saraj is a born adventurer. He is a born mountaineer and trekker. Saraj starts from Kontwara village and spreads westwards up to Rajgarh village of Ramban. Kontwara is situated on the right bank of Chenab across Kishtwar. Saraj is a large area. The main villages, which fall in this area include—Mahala, Malwana, Jodhpur, Jatheli, Babor, Bharat, Udainpur, Kulhand, Koti, Ganika, Bijarani, Bhagwah, Desa, Kashtigarh and Rajgarh. Desa Nallah divides this area into two unequal halves. Desa Nallah joins Chenab few miles from Chapnari on Chenab’s right bank. Saraj area is located on right bank of Chenab. No part of it is situated on the left bank; even our district headquarters, Doda, is located in the same area.'

He further explained the etymology of the word Saraz:

'As far as the etymology of the word Saraj is concerned, there are several versions. According to one school of thought, Saraj acquires its name from sou raje (hundred feudal lords). It is popularly understood that there were hundred feudal lords in this area, from where the area acquires its name. Another view is that the word Saraj derives its name from the term Swaraj (self-rule).' (Ram Singh, personal communication, 2011)

As the terrain of this area is very tough, Ram Singh (2011) is of the opinion that the area was a safe sanctuary for people who ran away from their kingdoms to avoid tax or persecution: ‘There are several mountains in this region, which rise at a perpendicular height of 80 degree-90 degree. This area is an easy abode for those who needed a hideaway. This area was considered a safe sanctuary for rebels. These rebels then established their own zones of influence––swaraj (self-rule).’

According to him, Muslims migrated to these areas due to natural calamities in Kashmir:

If we talk about Muslims, they have entered from the Kashmir side. The Northern boundaries of erstwhile Doda district touched the erstwhile Anantnag district of Kashmir. Whenever there were famines (kehtsaali) in Kashmir, people would cross the mountains and migrated to these areas. So many have come for trade and settled here. If you see Hindus of this region speak Saraji, Muslims speak Kashmiri. Muslims of our area can speak Siraji in addition to Kashmiri (Ram Singh, personal communication, 2011).

The major force that unites this sociocultural region is the local language, Sarazi. Grierson (1919), the famous linguist, describes Sarazi as a dialect of Kashmiri. However, locals believe that Sarazi has little in common with Kashmiri, which is widely spoken in this region. Sarazi, according to one commentator, falls in the group of western Pahari languages and resembles Bhaderwahi and Chambiali languages spoken in Bhaderwah area of Jammu and Kashmir and Chamba region of Himachal Pradesh, respectively.

Apart from language, geography, climate, and spread of flora and fauna also unites this particular belt. Dominated by oak (kharshu) and poplar (kaow) trees, the sloppy landscape of this area rises from River Chenab and its tributaries and goes up to alpine pastures. It is dotted with temples and mosques of similar sizes and styles, which make them indistinguishable from one another.

The village of Bhagwah is a revenue village. At present, it has 17 habitations, also known as gam. Of all these habitations, the habitations of Bhagwah and Siserwad each have an old haveli. Both these havelis are owned by Rajput families. The present day Bhagwah is a large revenue village divided into four panchayats: Upper Bhagwah A, Upper Bhagwah B, Lower Bhagwah A and Lower Bhagwah B. The relations between a single village and the wider social system of which it forms a part are complex, and very little will be gained by discussing at the outset these relations in abstract and formal terms. Béteille (1965) argues that it was possible to study within the framework of a single village many forms of social relations, which are of general occurrence throughout the area. Such, for instance, are the relations shared by Hindus, Muslims and Dalits, and those shared by landowners, tenants and agricultural labourers. These relations are governed by norms and values, which have a certain generality. The hierarchies of caste, class and power in the village overlap to some extent but also cut across.

The outside world enters the life of the villager in a multitude of ways. What happens in the state capital and other urban centres and even global events—like Quran desecration and controversial cartoons of the Prophet—is often discussed with keen interest by the residents. The village may be viewed as a point where social, economic, and political forces operating over a much wider field meet and intersect. Social relations overflow the boundary of the village easily and extensively. Kinship and affinity links people from the village to people in other villages and towns. Many members of the older families and lineages have become scattered. However, they continue to retain some contact with those who have stayed behind in the village. Similarly, there are outsiders in the village who regularly come and meet their relatives. This population includes long-term government employees, small businesspersons and army personnel.

The people

According to the 2011 census, there are 1,088 households in the village. The total population of the village is 5,907. Persons belonging to the scheduled castes number 240 (4.06 per cent) whereas only 130 (2.2 per cent) are from scheduled tribes. A whopping 58.8 per cent of the total population is illiterate. The condition of women is even worse as 71.2 per cent of them are illiterate. In the village setting, people distinguish themselves from others on the basis of religion, caste (zaat/biradari) and language.

The Muslims believe in one god, and follow the way of life laid down for them in Holy Quran. All the Muslims of Bhagwah belong to the Sunni sect of Islam. Initially, the Muslims of Bhagwah seemed a homogenous lot, at least to me. Although, soon I realised that they were divided into three sub-castes: Malik, Sheikh and Khanzi. Recently, some Bhatt families have also settled in the village. They do not follow village exogamy. They do not marry Gujjar-Bakarwals and Watals. One man, who had married a Gujjar woman, was often cited as the lone case in the village of a person marrying outside own biradari. Gujjars are also an endogamous group but they do not practice clan exogamy as is presented by some studies (Roy 2003).

There is only a single Watal (hierarchically lower in status) family in the village, but in Doda Town they are 300-400 in number. I remember an incident. I was sitting in the living room of Mushtaq Faridi, who was a District officer at Doda office of Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Languages. An old man came and sat on the ground as we were sitting on the sofas. Faridi-saab started telling me a bit about the Watals, the community the man belonged to. He told me that they spoke a different version of the Kashmiri language, but the Watal man interrupted him and said, ‘We are Muslims too.’ Faridi-saab smiled. He gave him a currency note of ten rupees and the man left immediately.

It is believed that Muslims migrated from parts of south Kashmir across the Pir Panjals to evade nature’s fury—famine and floods. These migrations, although, were not limited to such calamities only. Sometimes, it is believed, Kashmiris would migrate in search of new places for selling their goods. The failure of the shawl industry had once also rendered people homeless. Sometimes, migrations took place because of the ruler’s tyranny, to avoid excessive taxation (Kaw 1990). Faridi-saab argued: ‘If one says that every Muslim in the Doda belt is of Kashmiri origin that would be an exaggeration. A few families like the Gattus of Doda have converted to Islam much later. While Nehrus are Kashmiris, Mantos have central Asian traits. In the Dacchan area, a good number of Kashmiri Pandit families are living for centuries now (personal communication 2008).' Muslims of the area, however, believe that they have migrated from south of Kashmir. This assertion becomes all the more important when we analyse it in context of current political situation in the area.

Hindus of Bhagwah are not a homogenous lot. They are internally differentiated based on their caste. The main caste groups in the village include Rajputs, Brahmins, Julahas (also known as Bhagats), Chamars (also known as Harijans[4]) and Doms (as known as Mahashahs). Rajputs are numerically as well as politically a dominant caste group. The sub-castes of Rajputs include Bhotiyal, Bhadral, Rakwal, and Sombadia. There are also some Katoch families. Regarding the origin of Rajputs, Ram Singh (personal communication 2011), shares his view:

'Our ancestors have also come from outside. Most of them are from plains especially Rajasthan. During the Mughal period, many people migrated to other areas to avoid conversion. There were other reasons for migration. Resistance to taxation may also be one of the reasons. During Muslim rule, Hindus must have migrated to these areas to avoid jaziya, religious tax. They could only bring along their religion and the names of the places where they stayed. This belt has villages with names like Jodhpur, Udainpur, Kashtigarh and Rajgarh, which are quite similar to the names of towns and cities in contemporary Rajasthan. This trend also shows that many came here to avoid religious persecution, taxation or death. By coming here these people were able to keep intact their culture, language and religion. Hindus, as they came much before other religions, could be regarded as being the original inhabitants (Ram Singh, personal communication 2011).'

Caste across religious lines

The caste system was practised rigidly in the past. Caste-based stratification and ideas of purity/pollution were also applicable to Muslims. Muslims learnt these ideas from their neighbours. Both Hindus and Muslims considered the castes like Megh, Chamar and Dom, untouchable. Upper castes freely availed their services but practice of commensality was strictly prohibited. They would socialise their children not to visit ‘lower caste’ houses and avoid eating with them. Moreover, lower-caste people were not allowed inside upper-caste and Muslim households. Every time a lower-caste person saw upper-caste elders, they would remove their shoes and hold them in their hands. The upper castes would also control the way lower castes would dress or travel. During fieldwork I heard many a times that lower-caste persons were not allowed to wear white clothes or ride horses.

Interaction between various castes was also based on hierarchy. While Meghs were part of a few ritual ceremonies, Chamars and Doms were strictly kept away from ritual events. The area where the Chamars of the village lived was away from the main localities. Similarly, Doms also lived away from the centre of the village. Meghs, popularly known as Bhagats, had a separate locality called Oza. There was a clear-cut relationship between space and caste. Muslims also lived on the outskirts of the village. Hindu Chamars and Gujjars shared the same space. Chamars were brought from Samba, a town in the Jammu plains, to the village by the local landlords to work for them. The most distinctive aspect, which I observed during my interaction with these families of Chamars, was their language. They spoke Dogri, the language of Jammu plains, at home. Although, like most of the residents, they are polyglots. On the other hand, Meghs and Doms spoke Sirazi at home. Lack of knowledge of local language shows that Chamars came to the village relatively late. Villagers also claim that there was no history of inter-caste marriages in the village.

The language

The predominant languages spoken in Bhagwah are Sarazi and Kashmiri. Most people can speak or understand these languages. Raman Singh, a middle-aged school teacher, told me, ‘Muslims of the village spoke Sarazi but very few Hindus spoke Kashmiri. This shows that communities who come from outside have to learn the host's language.’ Sirazi can be considered this area’s lingua franca. Kashmiri is widely spoken all over the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In fact, it is the most widely spoken language in the state. Kashmiri-speaking people inhabit almost all the districts of Jammu and Kashmir.

Kashmiri speakers would often comment that the Kashmiri spoken in the cities of the Kashmir Valley is quite different from Doda’s. Adil Ahmed (personal communication 2011), who is a student at Kashmir University, Srinagar, pointed to the fact that the Valley residents would often make fun of the kind of Kashmiri spoken in Doda. The reason was that to their ears it sounded harsh and rustic. He further adds, ‘They do not consider us as Kashmiris, they call us Gujjars.’ In practice, most of the people are bilingual. They can also understand languages spoken in nearby areas such as Kishtwari and Bhaderwahi.

Self-defence

Several women, Hindu as well as Muslim, were bilingual. Some of them have learnt a third language under taxing situations of militarisation. During militancy, adult men would often go underground. Not being able to find them, the army would ask questions to the women in Hindi/Urdu. Since women could speak only Sarazi and Kashmiri, their answers would not make any sense to the army men. In frustration, they would beat the women. In order to save their skin, women acquired a foreign language––Hindi/Urdu. When I asked Rabia Bibi (personal communication, 2011) how her Urdu was so good, she replied to me:

Armywallahs taught me Urdu. Whenever they would come they would bombard us with all sorts of questions. How could we have answered, if we did not know their language (lit. zubaan)? They would beat us mercilessly. I learnt Urdu to save my skin.

The Army perceived women to be an indirect facilitator of militancy. According to them, local women cooked and cared for militants, sheltered them and kept their whereabouts hidden. Women were often alone at home when the army came looking for suspected militants. The ordeal of interrogation characterised by deep humiliation often lasted for hours due to the language barrier and, sometimes, they had to answer the same questions for days. To endure the harsh and inescapable rounds of questioning by the army men, these women acquired a new language.

Greetings

In Saraz, there are set rules by which people belonging to different communities greet each other. A Muslim greets another Muslim with the standard asalamalekum (peace be upon you) and is greeted back with walekum salaam (and unto you peace). When an elderly Hindu is passing through the market, he is addressed by Muslims—whether young or old—with adaab arz hai or adaab (meaning respect and politeness, and accompanied by a hand gesture). Sometimes, young Muslim students address their Hindu teachers with a namaste (I bow to the divine in you). It is also true for other institutions and organisations where an employer is Hindu.

Among Hindus, the system of greeting is more diverse as Rajputs form the majority of the Hindu population. They greet each other with jai deva. This way of greeting is done across gender and age. If a Rajput has to greet a non-Rajput, especially lower castes, they are greeted with Ram Ram and now sometimes with namaste. Jogis, who are ritual specialists, are greeted with an aseeb[5]. These systems of greeting are now supplemented with English ways of greeting—good evening, good morning and good night.

Conclusion

There are several local languages—including Kashmiri, Kishtwari, Bhaderwahi, Pogli and Dogri—which are spoken in Doda subregion. Locals—Hindus and Muslims—understand and speak these languages. However, now with the rise of militancy, linguistic boundaries are defined in terms of religious boundaries. While Muslims have started identifying and claiming their language to be Kashmiri, Hindus continue identifying with local languages such as Kishtwari, Bhaderwahi, Sarazi or Pogli, depending on their location in the subregion. In reality, many men are polyglots. I have seen a number of men speaking Sarazi, immediately switching to Kashmiri and occasionally talking to drivers and cleaners in Dogri. The same person will do all this. However, women due to their restricted mobility do not speak more languages. Some women, who are more mobile, of course, speak both the languages equally well. They also know basic conversational strategies in Hindi/Urdu/Dogri.

Language is an important part of people's life-world. In spite of the fact that people fiercely guard their linguistic choices, they claim to understand the language of the other. Of course, there are people in today's generation who consciously do not speak in the language of the other. However, they completely understand what the other is saying.

Sarazi has been a lingua franca in this region and has left a strong influence on the other languages spoken here. Though many no longer identify with Sarazi, they do accept the fact that their own language, which they share with people from outside the region, is influenced by Sarazi; they identify with the region Saraz. The geographical extent of Saraz and Sarazi-influenced-Kashmiri constitutes the zone of Saraz.

Notes

[1] It is said that one of the ancient Rajas of Kishtwar whose dominion extended beyond Doda persuaded one utensil maker Deeda, a migrant from Multan (now in Pakistan), to settle permanently in this territory and set up a utensil factory there. Deeda is said to have settled in a village which later on came to be known after him. With the passage of time the name Deeda has changed into Doda, the present name of the town.

[2] During the fourth invasion of Ladakh, Zorawar Singh was killed on December 12, 1841 by a Tibetan soldier in the battle of Doyo. On the death of General Zorawar Singh, Mian Jabbar Singh was sent as governor of Kishtwar in 1842 A.D.

[3] An official census 2011 detail of Doda, Kishtwar and Ramban (part of erstwhile Doda district of Jammu and Kashmir) has been released by Directorate of Census Operations in Jammu and Kashmir. See Table 1.1

[4] I am aware of the contested nature of the word. However, during the course of my fieldwork locals frequently used this word.

[5] Aseeb could be a corrupt form of word asees (blessing).

References

Govt of India. 1890. Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak. Jaipur: Vivek Publishing House.

Béteille, André. 1965 [2012]. Caste, class and power: changing patterns of stratification in a Tanjore village (third edition). New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Grierson, George Abraham. 1919. Indo-Aryan Family (Northwestern Group). Linguistic Survey of India Vol.8 (Part 2). Delhiː Low Price Publications.

Kaw, Mushtaq Ahmad. 1990. ‘Some aspects of begar in Kashmir in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries’. Indian Economic & Social History Review, 27 (4): 465-474.

Kotwal, N.C. 2000. Political and Cultural heritage of Bhaderwah, Kishtwar and Doda. Jammu: Jay Kay Book House.

Mahajan, Chakraverti. 2017. ‘An Anthropological Study Exploring the Contours of Hindu-Muslim Relations in Bhagwah Village of District Doda, Jammu and Kashmir’. Ph. D. dissertation, Panjab University, Chandigarh.

Rana, Sunaina. 2016. Society and Culture in Doda: An Outline. Sheeraza English: A Journal of Jammu and Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture and Languages. January-March, pp. 50-66.

Roy, Shibani. 2003. ‘Hindi Musalman: Vangujjar Transhumance in Uttaranchal’. Economic and Political Weekly. 38 (46): 4913-4915.

Zargar, Nasir A. 2004. The Valley of Chenab. New Delhi: Minerva Press.