On December 30, 1935, the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar witnessed the first appearance of a girl who had no real background in the dance of the dasis. It was unheard of that a Brahmin girl would publicly dance the art of the devadasis (temple dancers of south India). Over a thousand aficionados assembled for the event, more out of curiosity than real interest. A handful of diehard dissenters bent on sabotaging the event also sneaked in to damnify the dancer—Rukmini Devi. Thus was Rukmini Devi’s entry into the world of Bharatanatyam. Born on a rare date, Feburary 29, 1904, she was the sixth child of Sanskrit scholar and retired government engineer Nilakanta Sastry. The Sastrys had left their native Puddukotai to seek their fortune in Madras, where they took up quarters in 1912 and life changed for this family imperceptibly, particularly for Rukmini, who responded with zest to much she saw around her.

After the Sastry family moved to Madras, due to their proximity to many foreigners at the Theosophical Society, Rukmini got attached to a young English lady named Eleanor Elder, who had studied dancing with Margaret Morris in London and was now directing her attention to reviving the ancient Greek dance following the precedent of the redoubtable Isadora Duncan and her brother Raymond. To conduct her experiment and enquiry, Elder roped in some of the European and American residents at the Theosophical Society. Elder put up shows from time to time. In one of these shows, a Tamil version of Tagore’s Malini was performed, Rukmini appeared briefly and sang a song. This was 1918. The December 1935 performance proved to be a turning point in many ways—for Rukmini herself, of course, but also for the development of Bharatanatyam. The grand success of the performance led to the creation of a unique dance community in 1936 called the Kalakshetra. It had been conceived as an integrated community—a family. The residential cottage, the classrooms, the rehearsal hall, mess and administrative block were all cheek by jowl and there was energy in the air. There was Western discipline certainly, but old timers recall how after classes they could freely assemble and make small talk and bond as a family.

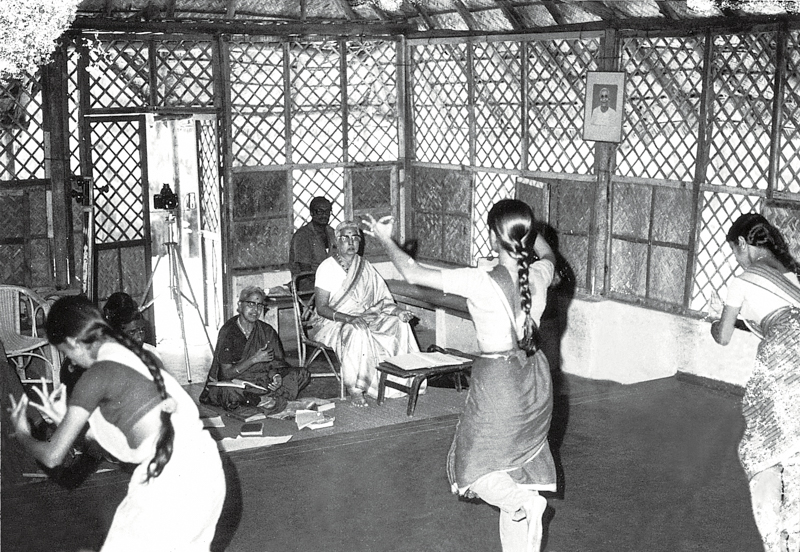

Rukmini Devi teaching at Kalakshetra, Periya Sarada accompanying her

At the Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society in 1940, George Arundale, its President and Rukmini Devi’s husband, declared: ‘Today it is a humble cottage, this Kalakshetra, but in due course we shall have buildings, beautiful, simple structures created by our own hands, the Temple to India’s glory. It is a cottage today; it will be a community tomorrow.’ Kalakshetra was at Adyar and both institutions were interlinked. For the first 13 years, the institution was on the Theosophical Society’s land at Adyar, but in 1948, Kalakshetra received an eviction notice from the Theosophical Society. This was a shock to say the least. The reason ascribed in the notice (a copy of which is in the Mohan Khokar Dance Archives given by Rukmini Devi herself) was that the dance and music activities were alien to the tenets of Theosophical Society and thus they could not host the institution.

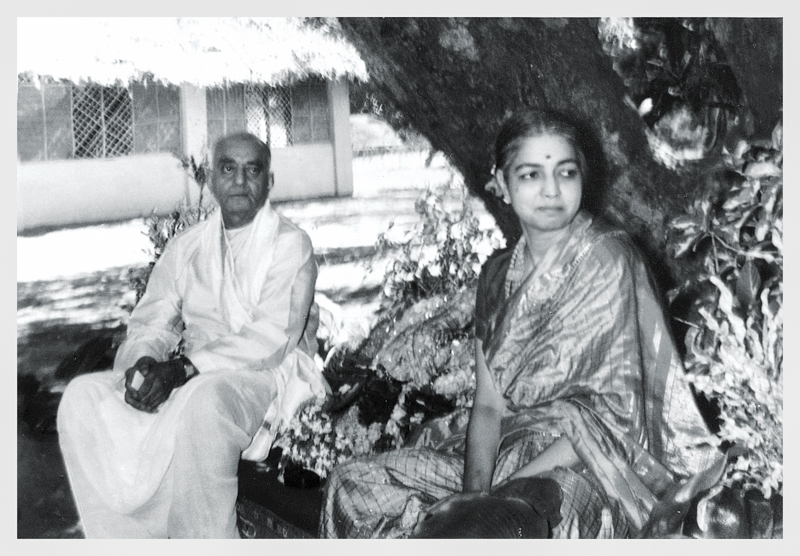

Rukmini Devi with her husband George Sydney Arundale

Kalakshetra had been formed when George Arundale was President of the Theosophical Society. Rukmini Devi was appointed the President of Kalakshetra and James Cousins the Vice President, while George Arundale and C. Jinarajadasa were patrons. At the inauguration, among those who spoke was Jinarajadasa who said:

Today we are starting an organisation for the arts. It is surely a logical development of our work. Indeed this is a lovely event today, that in this Theosophical Society we have realised so fully the need of art. I hope the academy (Kalakshetra) will give us the inspiration we all need, so that we will understand better our work and better our ideals of Theosophy.

Why then did the Theosophical Society so unceremoniously and suddenly evict Kalakshetra? After George Arundale died in August 1945, C. Jinarajadasa came to be elected President of the Society. He and his confreres soon started having second thoughts about Kalakshetra. The feeling was born, and nursed, that its pursuits were not quite consistent with the objectives of the Society. The showdown came towards 1949 when Kalakshetra was directed to quit the Adyar campus by the middle of 1953.

It would seem Rukmini Devi, as early as 1945, had some premonition of the contretemps. For, in that year, fearing that in coming years Kalakshetra might expand and the Theosophical Society not be able to provide additional space, she started buying pockets of land nearby. The place chosen was a neighbouring village called Thiruvanmiyur. Land was cheap, around Rs. 300 per acre, and, over the years, a great deal came to be acquired, though only in patches, whenever available. The institution we all see today stands on the land acquired thus.

In 1952 came another surprise turn. C. Jinarajadasa’s term finished and in his place came to be elected N. Sri Ram, a brother of Rukmini, who wished Kalakshetra to return to its original setting and moorings in Adyar and agreed to extend the lease for 15 years, but Rukmini Devi rightly refused. Such was the strength and suffering of this great woman, whom many worship today. Rukmini Devi also went on to create India’s Bolshoi, where training in dance and music were interdisciplinary. Kalakshetra, and Kalamandalam born around the same time of nationalistic resurgence and revival, became models for other institutions that came up in post-Independent India, such as the Kathak Kendra in Delhi.

Many of the Kalakshetra students distinguished themselves over the last 75 years of its existence, and include names such as Janardhan, Balagopal, V.P. Dhanajayan, C.V. Chandrasekhar, Yamini Krishnamurthy, Krishnaveni Laxman, Shanta Dhananjayan and Leela Samson. Many major dance drama (loosely called ‘ballet’) productions came out of this august institution and contributed significantly to the understanding of Indian arts and aesthetics. Among these, Rama Patabhiskeham, Rukmini Kalyanam, Ramanayam, Kutral Kuruvanji and Shabari remain milestones. None less than stalwarts like Tiger Varadachariar composed music and many distinguished aesthetes served as director, such as Sankara Menon, Rajaram and, in later years, Leela Samson followed by Priyadarshini Govind.

Kalakshetra production of Ramayana

Rukmini Devi rose to become a cultural icon of the country, once even considered for the presidential candidacy. She was a beacon for Bharatanatyam and its revival. History gave her that role and she used it well. She was also a champion of animal rights, vegetarianism and theosophy. In her twilight years, she ensured continuity. She passed away on February 24, 1986. Her legacy, Kalakshetra, still stands.

Research Associate: Ambika Panikar