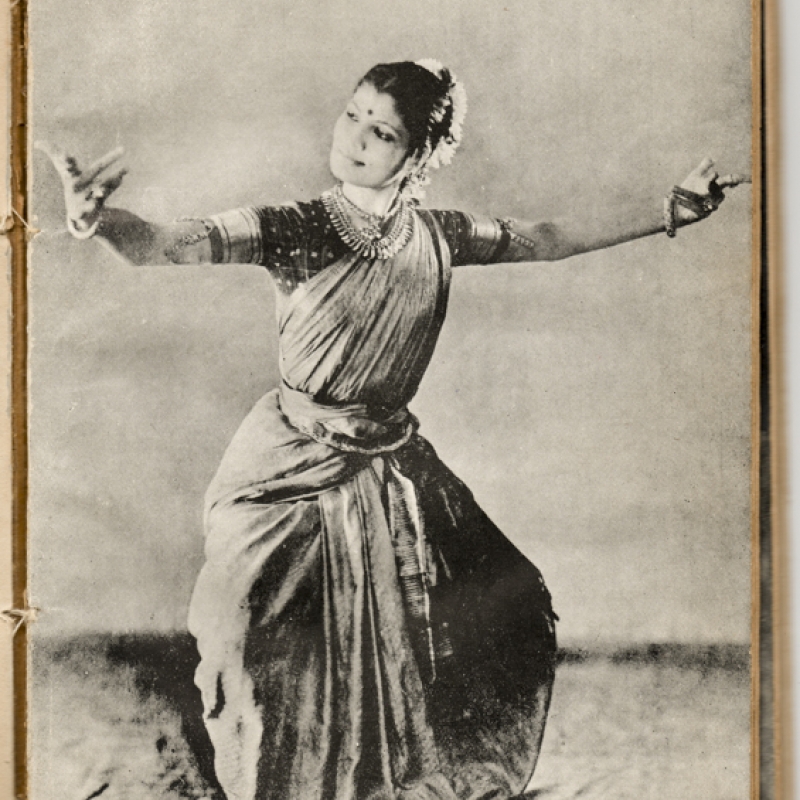

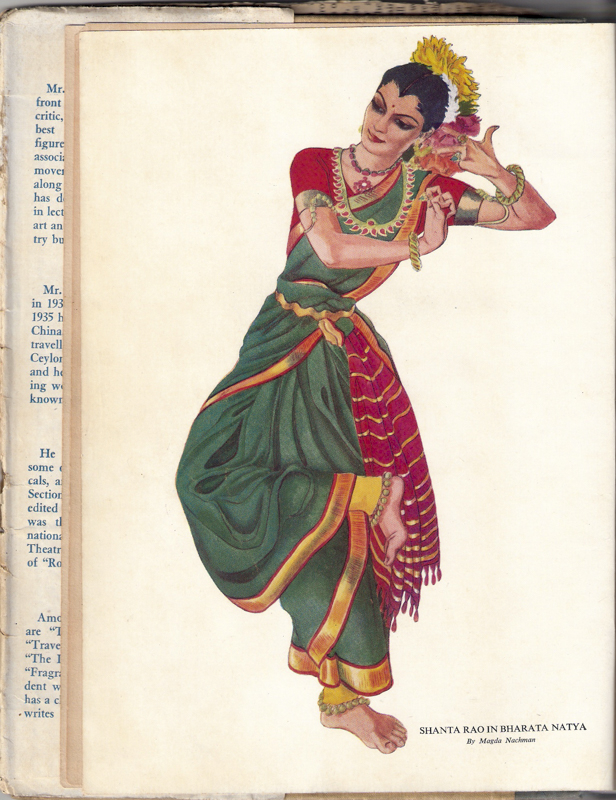

Shanta Rao made a mark as a strong woman dancer on the Indian stage. She was rather manly looking on stage for those days of delicate dancers, showing strength of body and mind, no wonder she could take to a masculine form like Kathakali with aplomb. She was a strange mixture of deep intellect, exuberance and very private life, an easily piqued and forever temperamental dancer. G. Venkatachalam, who was her fan more than an objective critic, wrote in his book Dance in India that he met her when she was about six years old in 1931, thereby one may surmise she was born in 1925, though dancers of that era never established their age conclusively, or liked anyone else to do so! Further on, Venkatachalam goes on to describe Shanta as a ‘tomboyish character, climbing trees, running around in knickers and mistreating animals. Her tyranny was for all to see…’

He writes how he was left to shoulder the responsibility of finding her a good dance guru, once Shanta decided, under his advice, not to go to college but to pursue dance. For this, she arrived at Vallathol’s Kalamandalam in 1939, and after a hard day’s training played in the river nearby! Venkatachalam notes that, ‘Shanta was only 15 but had beauty and genius, a combination to frighten even the stoutest of hearts and wisest of men.’

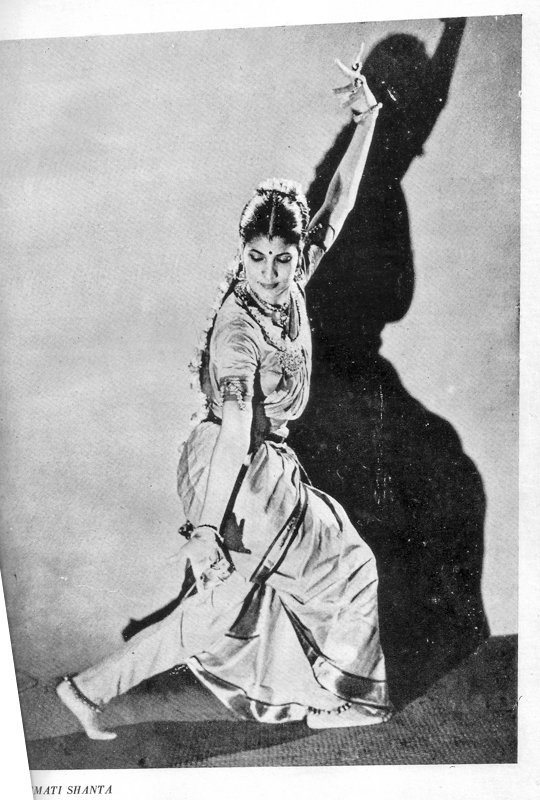

Shanta learnt Kathakali, the manly dance that sat well on her and suited her well. Later, she also learnt Mohiniyattam but that did not look so graceful on her big-boned frame. But she was in the right social circles and became well-known and remained so for long. Her Kathakali teacher, Ravunni Menon, was strict and she learnt Mohiniyattam from Panikkar. Her Kamatchi Varnam was famous. She danced with much verve and hard-hitting steps.

In the 1940s, she went to Sri Lanka and learnt Kandyan dances from Gunaya. He taught her Naga Vannama and Iradi Vannama. She was hailed by the Lankan press as modern-day Ambapalli (also known as Amrapali), the dancer who became a Buddhist nun.

Although Shanta had learnt many dance forms, she finally chose Bharatanatyam because by then it had become fashionable for girls from ‘good families’ to do so. She went to Pandanallur to learn Bharatanatyam and ended up at the doorsteps of the popular teacher, Guru Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, who noted that since she had learnt Kathakali first, teaching her was difficult as her motions were manly and actions dramatic. However, when her debut took place in 1943 at the Madras Museum Theatre, Egmore, she got rave reviews.

As her family was close to leaders of the Civil Disobedience Movement, and their home in Bombay was the meeting point for many, including poets and patriots like Harindranath Chattopadhaya, she benefitted by close association with the Congress party when India became independent and earned lavish praise from leaders like Sarojini Naidu. Pandit Nehru is known to have said, ‘Shanta, I never knew Indian dancing could be so beautiful.’

Shanta’s career, though versatile, was short. Talents like Kamala, Indrani Rahman, M.K. Saroja, Vyjayanthimala and Yamini Krishnamurthy came centre stage in the next two decades. On the whole, it was not easy to reach her: she had cut herself off from most and closed herself in and met no one except a few she wanted to or trusted, and remained a memory all through the '70s and thereafter. The last time anyone saw her perform was at Sangeet Natak Akademi’s Swarna Jayanti Mahotsava, celebrating India’s 50th year of independence, organised in Delhi in 1997. The Karnataka government under a benevolent and culturally enlightened chief minister, R.K. Hegde, had her given her largesse to build a performance space at home, however, she would let it out only occasionally. Shanta Rao died on December 28, 2007, almost unsung, alone, in her Malleswaram home, Bangalore.

(Photographs from G. Venkatachalam's Dance in India, and the Mohan Khokar Dance Collection)

Research Associate: Ambika Panikar