Anna Pavlova, the great Russian ballerina was born on January 31, 1881. A sickly child, she had more than her fair share of enervating illnesses, which included measles, scarlet fever and diphtheria. Notwithstanding her frailty, she was, at the age of 10, accepted as a pupil at the Imperial School of Ballet in St. Petersburg. From the very start, she demonstrated an exceptional facility for dancing, which enthused her teachers to give her more than the usual attention. On graduation, she was immediately absorbed as a group dancer in the School’s theatre, the Marinsky. Within five years, she rose to become a prima ballerina, a stage which most dancers do not reach in a lifetime.

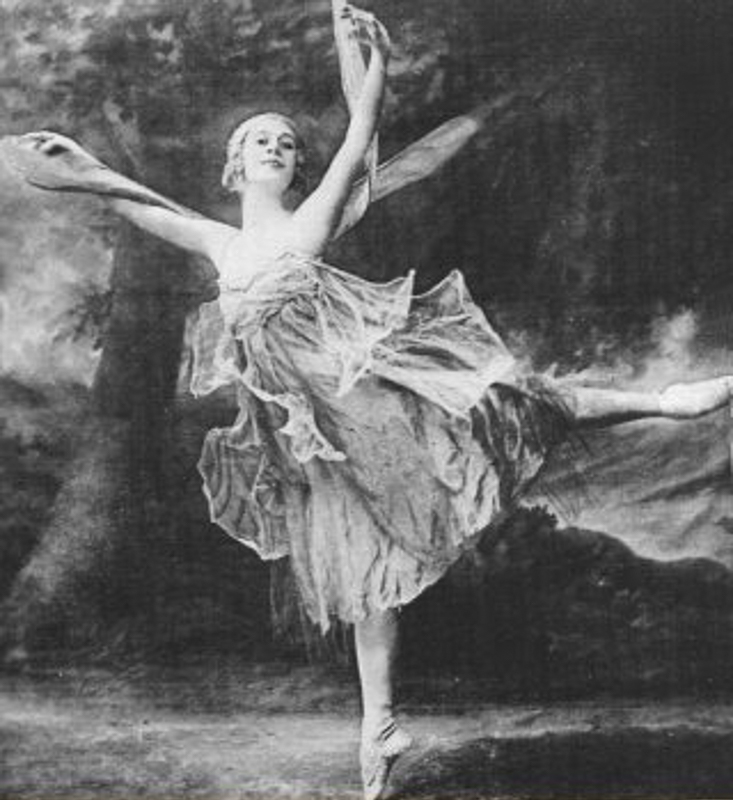

On the 10th anniversary of her joining the Marinsky, Pavlova appeared as the lead dancer in a new ballet—La Bayadere. This is based on the life of a devadasi who is loved by a Hindu priest, but herself loves a gallant in the local raja’s service. Pavlova’s involvement with India started from this time.

Pavlova in La Bayadere

On her very first visit to India in 1922, though she travelled a good deal, all that she could see by way of dancing was some crude and clumsy nautch[1] in Calcutta. This is what provoked her husband and manager of the company, Victor Dandre, to lament, 'There are no schools of dancing in India and it is an art in which nobody is interested.' Pavlova left Russia in 1913 and made London her home. She formed her own Company with which she toured the world more than once, and until her last days. Everywhere she went, she was met with enormous success and was heartily hailed and feted. More than any other solo dancer, it is because of Pavlova that the art of ballet came to be known for the first time in many countries. On her journeys around the world she made it a point to mix with the local people, to understand their customs and habits and to see their dances. Japan and India appealed to her the most. And this is what led her to conceptualise one of her most ambitious presentations, Oriental Impressions, a compilation of short ballets interpreting the dance of these countries.

Pavlova in Dragon Fly

Of her India visit, the lasting impressions Pavlova carried was of the Ajanta frescoes. On her return to London, she deputed her staff choreographer Ivan Clustine to create, for her, a ballet on the theme. Simply called Ajanta Frescoes, the effort remained amateurish, for Clustine had never seen the frescoes nor had any idea of Indian dancing. It was received variously. While the Daily Mail opined that it was 'worked out with brilliance, with a colour of its own,' the Saturday Review ticked off the produers with, 'Frankly, a tedious spectacle copied with a wealth of superfluous accuracy from the dreary Buddhist art of India.'

In India, Pavlova had occasion to attend a wedding, and now her attention turned to producing a ballet on this. Harcourt Algeranoff, a leading dancer with her, was directed to pore over books and visuals, to cull out ideas for the wedding ceremonies and for the costumes and setting. Next began the search for a music composer. Right then Dandre discovered an Indian, Commalata Bannerjee, was giving concerts in London. The audition clinched and she was commissioned to devise the music for the ballet, which was given the straightforward name—A Hindu Wedding. But Ms Bannerjee made a greater contribution than this. She referred Pavlova to a young Indian boy who was in London studying painting, and also dabbled in dance, who might prove of help to Pavlova in designing the ballet. The boy was none other than Uday Shankar!

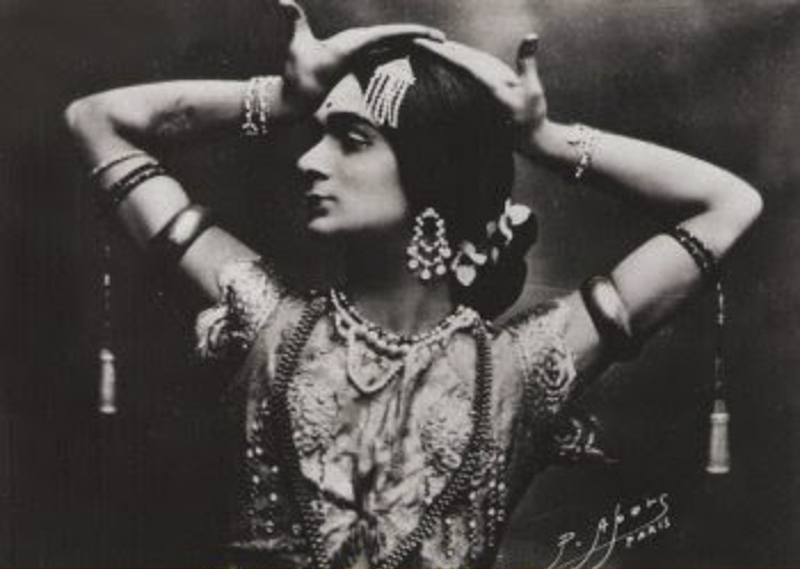

Uday Shankar as Nautch girl

Thus Anna Pavlova discovered Uday Shankar, as a dancer, for he not only designed but also choreographed A Hindu Wedding. He also choreographed another ballet for her, Krishna and Radha, in which Pavlova invited him to partner her on stage. Thus, India’s greatest genius in dance was born. The two Indian ballets became part of Oriental Impressions, and Uday Shankar, purely by accident, was launched on his dance career.

Four years later, in 1927, another fortuitous development took place. A personable young Indian lady in London, Leila Sokhey, met Pavlova and bemoaned that though she had been very keen on learning dancing in India, she could not make any headway. Pavlova immediately assigned Algeranoff to teach Leila Sokhey. Leila Sokhey was none other than Madame Menaka, a name she assumed when she returned to India and took to dancing full-time and founded a school in Bombay. When Pavlova visited India the second time, in 1928–29, Menaka persuaded Algeranoff to work with her for a while. Together they choreographed and staged three dances, of which the most notable was Naga Kanya Nritya.

Though she had reservations earlier, on her second visit, Pavlova made bold to present her Oriental Impressions. In Krishna and Radha, the role of Krishna was taken by Algeranoff. Both this and A Hindu Wedding were received extremely well. When in Calcutta, Pavlova wrote to Tagore if he could suggest any of his poems on which she could make a ballet. He sent her one such poem and urged her to visit him so he may discuss how this translated into dance. Travelling to Santiniketan being far from easy, Pavlova could not make it and so the dance never materialised.

In 1929 transpired another far-reaching event. Pavlova and her Company had embarked from a port in Java to travel to Australia and it so happened that the same ship was carrying, right opposite her cabin, a young Indian bride, Rukmini Devi, and her husband George Arundale. The encounter clicked, and on reaching Australia, on Rukmini’s insistence, Pavlova entrusted one of her principles, Cleo Nordi, to teach the rudiments of ballet to Rukmini Devi. Thus did Rukmini Devi become yet another one to enter the world of dance because of Pavlova.

There are many other ways, too, in which Pavlova became a catalyst for Indian dance, then re-merging, to find a place on the world stage. Indian dance owes a lot to Anna Pavlova, who died on January 23, 1931.

Research Associate: Ambika Panikar

Endnotes

[1] 'Nautch' was the derogatory term British colonizers used to project Indian dance traditions. It was only in the 1940s that this pejorative term slowly faded out of use.