Uday Shankar, a cult figure in the world of dance, was born in Udaipur, Rajasthan, on December 8, 1900. The first child of Shyamashankar Choudhury and Hemangini Devi, he was named after his place of birth. His father was in the service of the Maharaja of Jhalawar, and his work required him to travel from place to place. Thus the childhood of Uday and his three younger brothers, Rajendra, Debendra and Ravi, was spent at their maternal home in Nazratpur village near Varanasi.

It was during those early years, while watching the energetic Chamars (leather workers) perform during the Holi festival, that Uday first became aware of an interest in dance. In fact, later Uday acknowledged their lead dancer Matadin as the first one to inspire him. Many a times would Uday and his friends slip away to watch folk dances and even the forbidden ‘nautch’. Having no interest in structured learning, he much preferred boisterous activities like swimming, rowing or street entertainment. Along with all these activities, he also discovered a liking for painting. Ambikacharan Mukherjee, his art teacher, acknowledged his talent, and while nurturing his pupil’s creative potential, also introduced him to fields like music, photography and magic. This exposure, at a later date, was to change Uday’s life. When Uday was 14, his father, who had been staying in London, returned after the outbreak of World War I. Thereafter the family moved to Jhalawar. The Maharaja was so impressed by Uday’s talent in painting that he convinced Shyamashankar to enrol Uday at the Sir J.J. School of Art. And so, Uday’s formal training in art began at that reputed institution in the year 1918. After completing the diploma course, Uday Shankar boarded the SS Royalty and set sail for London on August 23, 1920. He joined the Royal College of Art, London, for higher studies. Under the influence of Sir William Rothenstein, the principal, Uday Shankar managed to complete the five-year course in just three years. At that time, he also won two coveted prizes, one for a self-portrait and another for a painting titled Dance in Moonlight. The paintings grew and almost all of them were developed around Sri Krishna. However, the style and technique were modern European. It was Rothenstein again who urged him on to delve more deeply into his own culture. And so, Uday spent almost a month at the British Museum, reading books on Indian art—miniature painting, cave painting and sculpture.

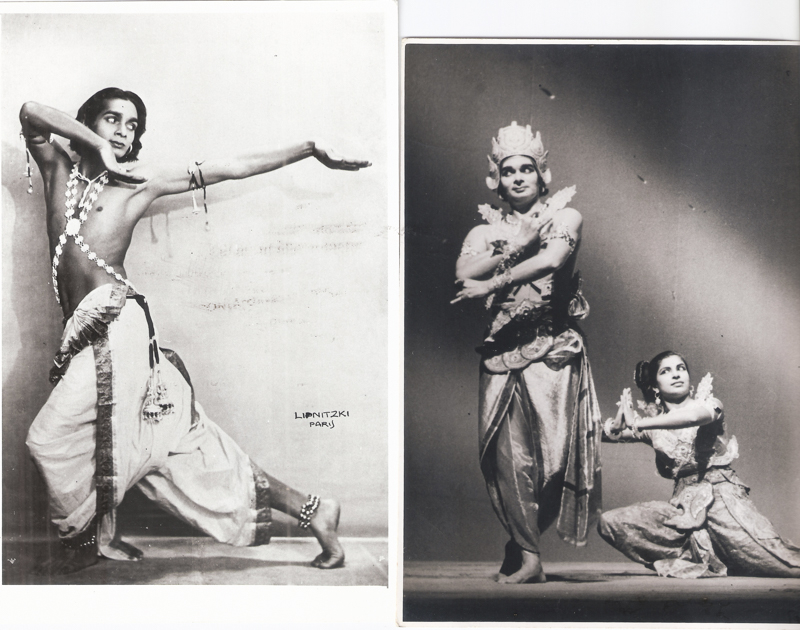

Thus began his fascination with pictures of Indian sculptures—gods and goddesses in various dancing poses. Noting their communicative powers, he began imitating the poses. Although not a trained dancer, he did not hold himself back, as for him the images were inspiration enough to translate them into movements.

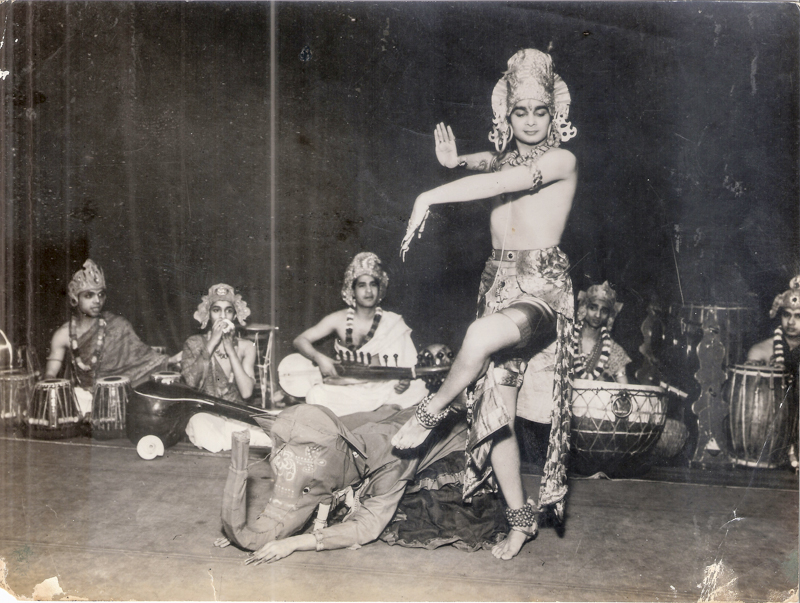

Uday Shankar performing Shiva Tandav; Ravi Shankar blowing the conch

Uday Shankar presented his first dance performance on June 20, 1922. Organised by the League of Mercy, the occasion was a garden party. Replete with swords and daggers and titled ‘Sword Dance’, the presentation garnered congratulations from King George V who witnessed it. It was fortuitous that the ballerina Anna Pavlova was on the lookout for music composers and choreographers for the miniature ballets on Indian themes that she was planning to produce. Pianist Commalata Banerjee had been asked to compose the music. Uday Shankar’s name was suggested to Pavlova by N.C. Sen, an official at the India Office. This led to a meeting between Pavlova and Uday at her Hampstead residence, Ivy House. Uday charmed Pavlova when he reproduced some of the Indian sculptures he had seen as a series of breathtaking movements. The rest, as they say, is history.

Uday Shankar undertook the responsibility to choreograph two ballets—‘Hindu Wedding’ and ‘Krishna and Radha’—for Pavlova. Their first performance was at Covent Garden, London. It won critical acclaim from the press and the public alike and both the lead dancers received a lot of praise. Uday Shankar joined Pavlova’s troupe as a dancer and toured Europe and the USA for nine months. He was beginning to veer towards Western dance but was discouraged by Pavlova in this and advised to investigate deeper into the intricacies of Indian dance. Provoked by this and also recognising the truth of what she advised, Uday Shankar left Pavlova’s troupe to embark on a journey of self-discovery.

Uday Shankar with Italian sisters Adelaide and Sokie

He went back to London and thereafter to Paris and fell on hard times. Sadly, the rave reviews received while dancing with Pavlova did not help him get more shows. To survive in an expensive city like Paris, Uday danced wherever he was given an opportunity—cabarets, revues, music halls, shabby haunts of the drunken. But these experiences also taught him lessons in raw appeal and connecting with the audience. The pieces that he performed those days were ‘Sword Dance’, ‘Nautch’, ‘Hindu Dance’ and ‘Water Carrier’. Two sisters, Adelaide and Sokie, both former members of Pavlova’s troupe, became his dance partners. Michelle Damour was another who partnered with Uday for a long time. But the one to partner him for the next two decades was Simone Barbier, a Paris-based pianist. She gave up the piano for dance and was renamed ‘Simkie’.

With Simkie, a new era began. Uday Shankar started choreographing newer dance pieces, both solos and duets. The partnership of Uday Shankar and Simkie soon became immensely popular and the duo was soon being invited to present numerous shows. In 1926, while touring Europe, Uday Shankar met Alice Boner, a Swiss painter and sculptress. Fascinated and deeply impressed by Uday Shankar’s dance, she did a series of clay models and drawings of Uday Shankar in various dance poses. They met again in 1929 in Paris and grew close. When he decided to travel back to India to seek out trained dancers and musicians for his troupe, she volunteered to accompany him. They set sail for India on January 4, 1930.

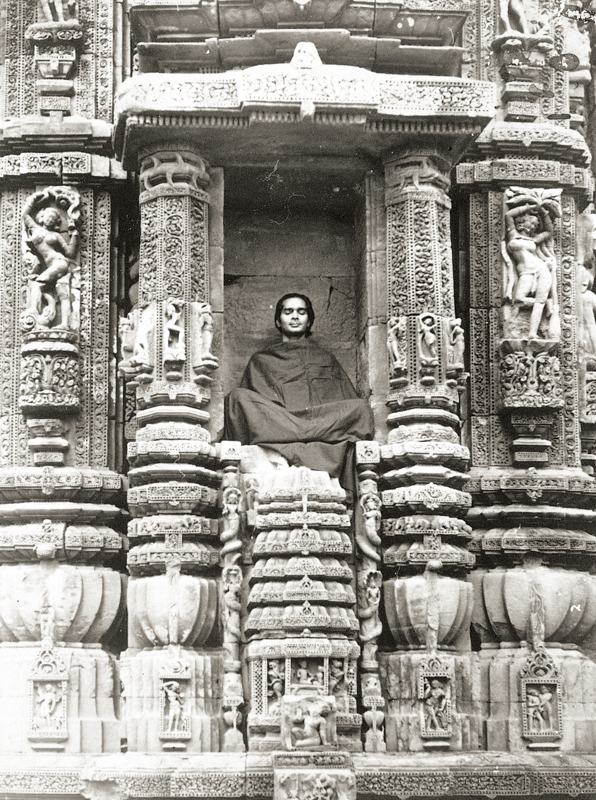

Once in India, they travelled the length and the breadth of the country. It was the India of temples, sculptures, frescoes—one that Uday had never seen before. And Uday recalled the advice of Rothenstein and Pavlova. Realising the financial difficulties in maintaining a troupe, Uday had hoped to find some sponsors in India but to no avail. Alice Boner then stepped in and supplied financial support. Uday was also having problems employing male and female dancers, the stigma to dance still being strong. Finally, he put together a sort of family group comprising his brothers, cousins, uncles, friend, Timir Baran (a sarod player) and even his mother—to look after the small matters, and of course Alice Boner.

Uday Shankar at Konarak

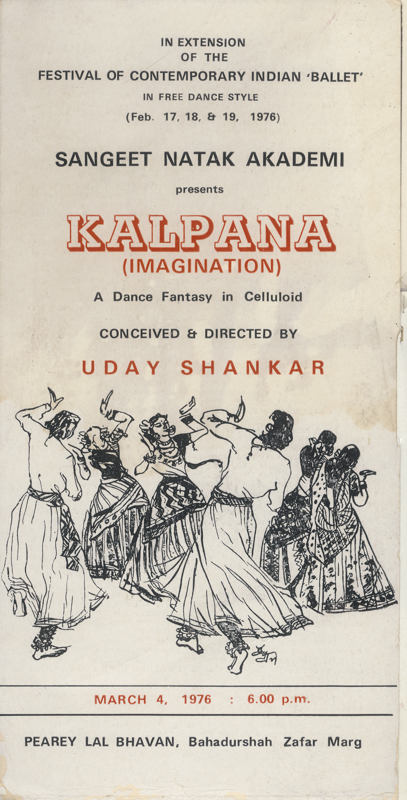

In October 1930, this troupe headed for Paris where they were joined by Simkie and another musician, Vishnudas Shirali. The new members never having danced earlier, they were put to rigorous training, while Vishnudas Shirali and Timir Baran worked on composing the music. After four months, the first performance of this new group was presented at the Theatre Champs-Elysse. It was a huge success and garnered them many more performances and tours. It was here that Uday Shankar met Sol Hurok, the well-known American impresario who booked the troupe for the next American season. The troupe disbanded a few seasons later. But Uday Shankar, fresh from his success, soon put together another team of dancers and musicians. With this new troupe, Uday toured Europe and America in 1938. At the end of these seven years of constant travel and performance, Uday Shankar announced his desire to return to India to set up a national centre for dance and music. With the support of the founders of Darlington Hall (near London), the Elmhirsts and Miss Beatrice, Uday Shankar’s dream was translated into reality as the Uday Shankar India Culture Centre at Almora. But the dream was short-lived. Due to reasons best known to the people involved, the centre closed down in 1944. One of the reasons could be his moving to Chennai to give shape to another ambitious project—Kalpana, a film about dance. The film, now an acknowledged a classic, did poorly at the box office everywhere, other than Kolkata. It ruined Uday financially.

Handbill of Kalpana

After this, for the next 30 years, Uday Shankar was based in Kolkata, grooming not only his own children Ananda and Mamata but a multitude of others as dancers. After several full-length ballets, Shankar’s swansong appeared in the 1970s as ‘Shankarscope’, a blend of film, stage, dance and drama. This work showed his grasp over all aspects of stagecraft.

Having lived a magical existence, he died an ill and broken man on September 26, 1977.