The Bhaibands, a Hindu trading community located in pockets all around the world today, originated in Hyderabad, Sindh, a town situated in India until Partition in 1947.

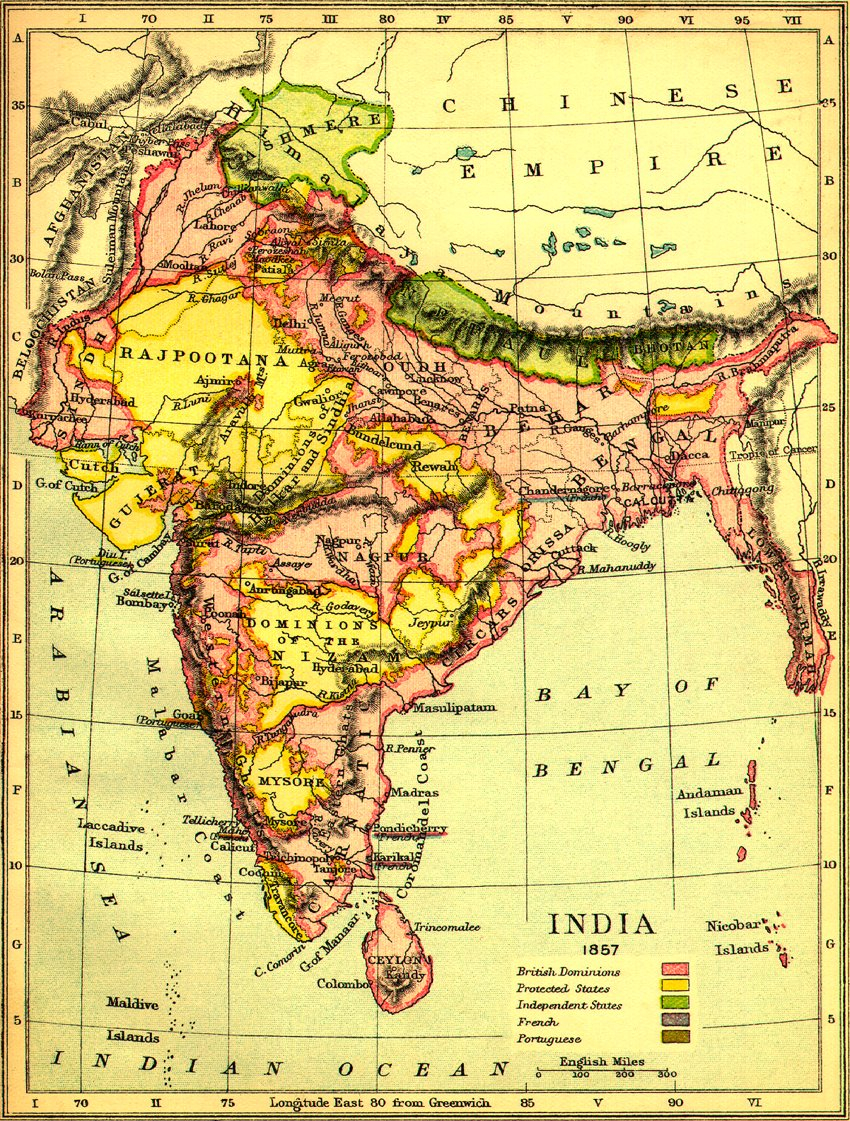

Map of India in 1857 (viewed on November 27, 2016)

The Bhaiband Sindhworkis emerged from the determined efforts of a few individuals to grow their trade beyond the province of Sindh. The success of these efforts drew more aspirants and their population grew. As one location became saturated, the adventurous ones moved on to the next one. By the time Partition came, their outposts were encircling the globe.

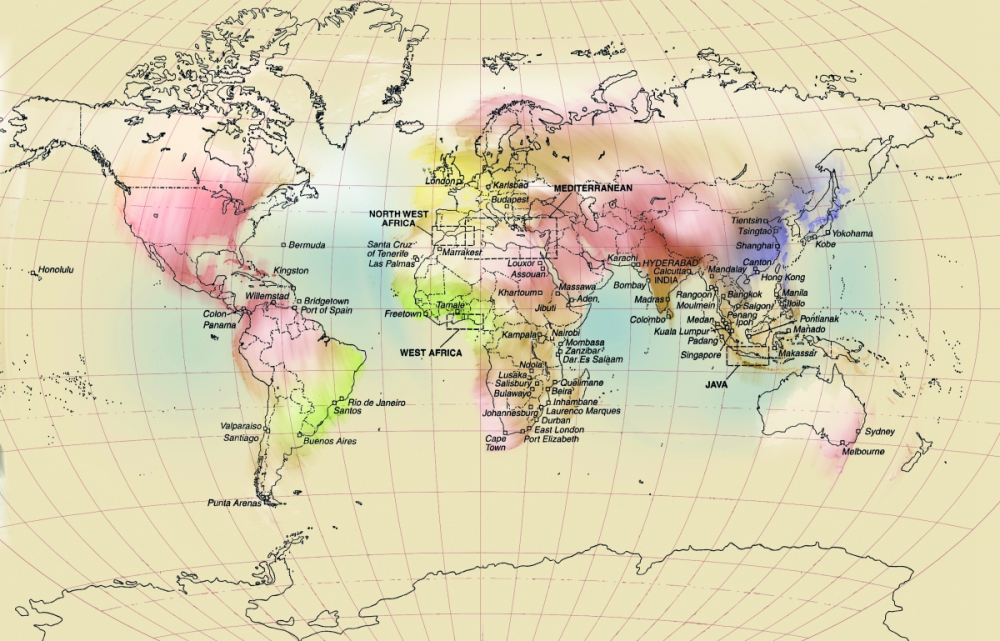

All localities marked on this map had branches of Bhaiband firms with headquarters in Hyderabad, Sindh.

Image courtesy Heritage India, based on research by Claude Markovits and designed for 'Heritage India Keepsake Collection', Issue 1

Despite their omnipresence, not much is known about the Bhaibands. They have received little attention in either popular awareness or academic literature. It was a French scholar, Claude Markovits, who first gave a detailed account of how this group of South Asian merchants managed to carve a niche for themselves in a European-dominated world economy. His seminal work was published 150 years after the first Sindhi entrepreneurs set out on their exploratory voyages.

A hub of trade since prehistoric times

The first long-distance trade is said to have taken place between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley around 3000 BCE. Thatta, a city in Lower Sindh, is believed to be the port town on the Indus delta, Patala, where Alexander the Great built his dockyard (c. 350 BC), one of the global centres of business and manufacturing as well as of culture and learning at that time. Four centuries later, the Romans wrote of Thatta as a trade crossroads. In time, Sindh became established as an important node in the Indian Ocean trade networks. The 12th-century Islamic geographer Al-Idrisi describes Sindh, its cities, diverse population and range of products, and the bustling trade between Indian, Chinese and Omani traders in the town of Debal, a port near present-day Karachi. He writes of Al-Ror and Sharusan, present-day Rohri and Sehwan, as large towns with many merchants and bustling markets (Falzon 2004). Marco Polo, in turn, wrote of the curiosities of Chin and Machin, and 'the beautiful products of Hind and Sindh, laden on large ships which sail like mountains with the wings of the wind on the surface of the water' (Polo 2014).

At Ibrahim Hyderi Fishing Harbour, Korangi Creek, Karachi in 2009. Local craft such as these have plied these waters since time immemorial, engaging in trade and sometimes in piracy.

Photographer: Rumana Husain, author of Karachiwala (2010).

In her interview, Radhika Seshan gives an overview of this trading world of Asia, describing the patterns and cycles of trade and explaining what gave Sindh the specific advantages which allowed it to participate in trade of both land and sea routes.

The 17th-century Sindhi epic poet Shah Abdul Latif has also written about the sea trade out of Sindh. He describes flourishing ports on the banks of the Indus, and sings of the sturdy boats of the traders, decorated with flags and gold-topped sticks made of ivory and expensive wood. His poems specify trade between Porbunder, Aden, Sri Lanka and the Far East, and he writes of how traders would sail with the monsoon winds to get home, returning to their trading posts a few months later, after Diwali. Shah Latif describes the perils of the seas these hardy adventurers faced: pirates, storms and goods ruined by sea and wind. A Sufi mystic, he is using metaphors for the spiritual life when he cautions the boatman to keep his oars and sails ready and his boat polished and shining, and when he advises him to stay alert to escape the pirates. However, his depiction in Sur Samundi of the bereft wives left behind is not metaphoric but in fact a realistic portrayal of the situation of the Sindhworki women in the years to come, revealing itself to be a centuries-old tradition.

Contemporary Sindhi poet, Govardhan Sharma (Ghayal), speaks about Shah Abdul Latif and his references to the sea trade from Sindh in the 17th century.

By this time, the produce of Sindh was also being exported profitably by the Portuguese (who pillaged and destroyed Thatta in the 15th century to such an extent that it was never able to regain its importance (Khuhro 2000) and then by the Dutch. Mark Anthony Falzon writes of references to local Hindu traders in the records of the Dutch East India Company (VOC): 'In 1757 the Dutch merchant Brahe met a group of merchants from "Karaatje" (Karachi) whom he had engaged via a local broker named "Annendramme" (Anand Ram); the merchants inspected Brahe’s spices and sugar and offered to buy them on condition that two to three months’ credit would be extended, saying that they could get the same goods at better prices from the English' (Falzon 2004).

Many British historians and administrative officers have written of the changing course of the Indus which constantly destroyed towns and ports while creating new ones. They have described the glory and the roaring trade of Debal, Lahari Bandar and other ports of Sindh. 'The Early British Traders in Sindh' by Advani (1934) is an account of the first attempts the British made to trade in Sindh.

The oldest recorded merchant community from Sindh are the Bhatias of Thatta who formed, from the late 15th to the early 19th century, the bulk of the large Indian trading community in Muscat. From the late 18th century, the Sindhi Khojas played an important role in the trade in the Western Indian Ocean. The inland city of Shikarpur also gave rise to a major network which extended from Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea to the Straits of Malacca. Their hundis (promissory notes) were the major currency on the caravan routes of Central Asia and in India (Markovits 2000).

With this long tradition of trade and merchant mobility, and with its own rich range of products, in the 19th century the inland city of Hyderabad gave rise to another extraordinary community which Claude Markovits describes as ‘the most extensive of all Indian merchant networks abroad, which around 1947, stretched from Kobe in Japan to Panama, with several firms having branches in all the major ports along the two main sea-routes, Bombay—Kobe (via Colombo, Singapore, Surabaya, Saigon, Canton, Shanghai, Manila) and Bombay—Panama (via Port-Sudan, Port Said, Alexandria, Valletta, Gibraltar, Teneriffe, or alternatively via Lourenco—Marques, Capetown, Freetown). By 1937, it was estimated that there were 5000 of these Sindhworkis, who specialized in the sale of silk and curios, scattered across the world' (Markovits 2000).

Sindhwork

Soon after the British annexed Sindh in the mid-19th century, they began attempting to describe the tribes and races they colonised from their point of view. Accordingly, the 1876 Gazetteer of the Province of Sindh says:

The people inhabiting the province of Sindh may be divided into two great classes—the Muhammadans and the Hindus, the former being by far the more numerous and comprising quite two-thirds of the entire population.

Of the Waishia, Wani or the Banya caste, there is one great family, the Lohano. It is as usual divided and subdivided almost ad infinitum, but the distinguishing features of the race are still sufficiently prominent. To treat of the Lohano caste is to describe the main body of Hindus in Sindh.

The Lohano may be divided into two great classes according to their several occupations: First, the Amils or Government servants: and secondly, the Sahukars, Hathwara, Pokhwara, &c., i.e., merchants, shopkeepers, agriculturists, & c. & c.’ (Hughes 1876:86, 92, 93).

The Hindus who had taken to education and the knowledge of Persian had thereby acquired responsible positions in the courts of the Mirs. Sindh had no rigid caste system, but this group formed a division of educated Sindhis and was given the name ‘Amil’, a word derived from ilm, the Persian word for education and also related to amal which refers to administration. The Amils quickly learned English and took to the education the new rulers imposed, and the British welcomed these industrious and trustworthy administrators into their empire.

The larger Hindu group was of the traders, some of whom had small holdings of land. Things were more complicated for them. With an eye on trade, the British had entered Sindh with well-entrenched cartels that had their own legacies of methods and movements. They imposed new taxes, monopolized trade in products and restricted markets. The British also brought their own treasury system, and the bankers of Hyderabad, who had previously financed the state, had to find new outlets. When the Company rupee was introduced as legal tender, they lost their thriving business in currency exchange.

The British also created new infrastructure: post and telegraph networks, new metalled roads, canals to distribute Indus water and river transportation. Work began on the Sindh Railway. Transportation of goods became easier and there were systematic efforts to display goods and create new markets. In December 1869, the first Industrial Exhibition of Sindh was held in Frere Hall and described in the Gazetteer:

In the extensive rooms of the Hall were arranged a varied assortment of articles, the productions not alone of Sindh, but of the Punjab, Bahawalpur, Kachch, Afghanistan—of several of the districts of the Madras and Bombay Presidencies, and of other places as well. In livestock the show was not considered to be favourable, but in agricultural and animal products it was extensive and creditable. The display of dyes, cotton, fibres, drugs, oil and ghi, the produce of Sindh itself, was held to be good, and many of these items obtained prizes. In forest and mineral products, and in materials used in construction, the building stone of Sindh, as also its salt, saltpeter and different parts of woods, attracted attention, and won several prizes. In skin and manufactures, the carpets made in the Shikarpur Jail—the gold, silver and silk embroideries of Hyderabad—the lacquered ware of Hala and Khairpur—and the lungis of Thatta occupied a prominent place, and were deservedly admired. (Hughes 1876)

The website of the British Library has a photograph of a potter from Hala taken by Henry Cousens in 1894 (Cousens, 1854–1933, Scottish archaeologist, artist and archaeological photographer, was Superintendent of the Archaeological Survey of India, Western Circle, 1909 to 1910):

Hala, 35 miles north of Hyderabad, was the main centre of pottery manufacture in Sindh. Both tiles and ornamental pottery are produced at Hala. Due to their reputation, the potters of Sindh and Multan were brought to the Bombay School of Art to superintend. Hala continues to be a centre of Sindhi craft production in present times.' Copyright © The British Library Board

The Sindhi entrepreneurs at the centre of these developments were quick to adapt to the new conditions and discreetly seek new opportunities. Transportation of goods had become easier. Bombay, with all its opportunities, was much more accessible.

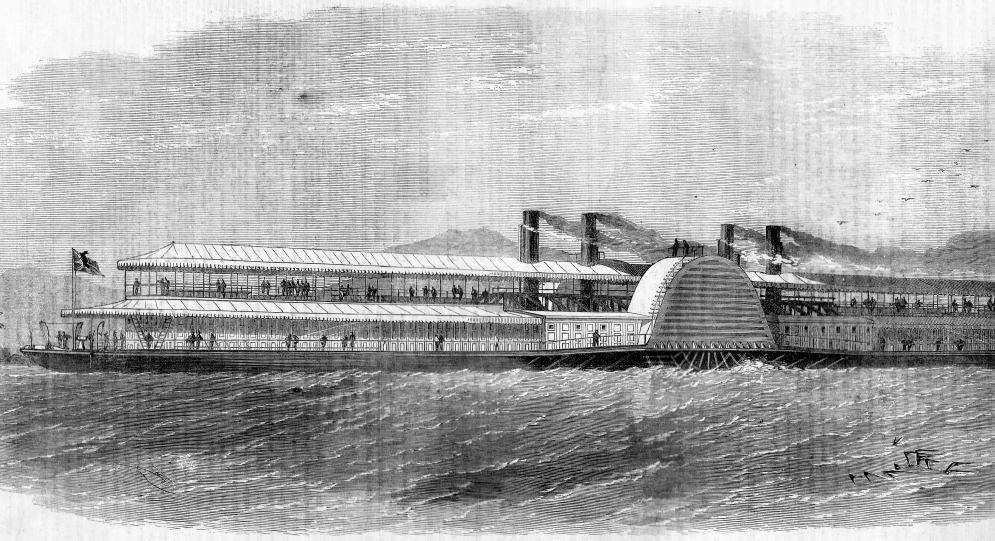

An illustration in the Illustrated London News in February 1861. Designed by T.B. Winter and built by M. Pearse and Co of Stockton-on-Tees, this vessel had four funnels, 377 feet in length, 74 beams and 5 feet in depth but only 2 feet draft, 739 tons and 220 nominal horse power. She had room for 800 troops with an ingenious method of cooling their accommodation and managed 12 mph during her trials on the Thames. Later named Talpore, she was the largest river steamer of her time, which must have been impractical given the nature of the Indus.

Image source: http://www.victorianweb.org/victorian/history//empire/india/images/2.jpg (viewed on November 27, 2016).

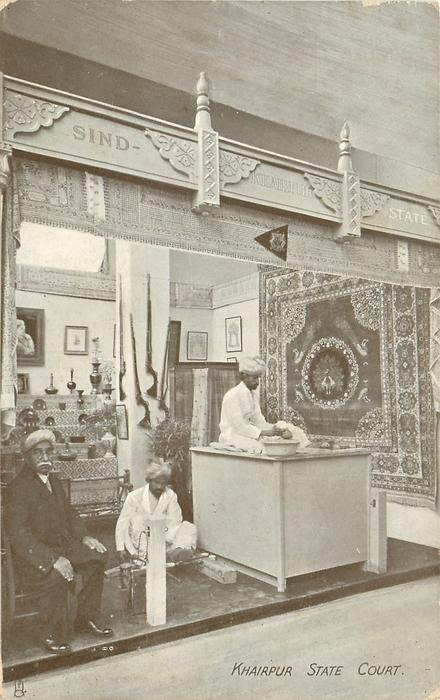

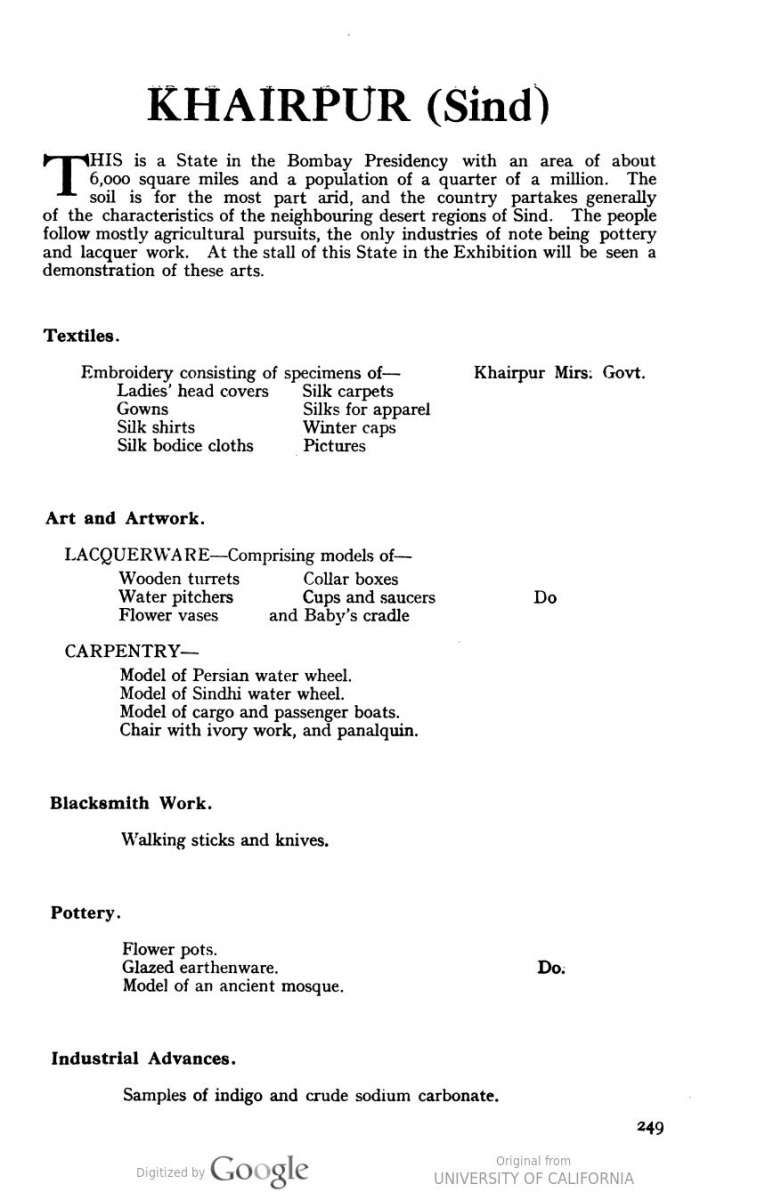

The Khairpur stall at British Imperial Exhibition 1924. Image source: Tuck D.B. Postcards

The produce of Khairpur as listed in the catalogue of the British Empire Exhibition 1924.

Image source: India: Souvenir of the Indian Pavilion and its Exhibits: Souvenir of Wembley 1924 (Wembley: British Empire Exhibition, 1924)

The British themselves were keen buyers of Sindhi handicrafts. They loved the products displayed in the exhibitions, the carpets, lungis, embroideries and lacquered ware, and soon also discovered the beautifully coloured nested boxes, ajrak from Dadu and brass and kansa work from Larkano. They not only bought these things for themselves, but when they were going back on home leave, they filled their steamer trunks with Sindhi handicrafts which were called ‘Sindhwork’.

Before long, the first Hindu trader packed a trunk of his own filled with ‘Sindhwork’ and set out on a ship sailing west to seek his fortune.

Groups of British officers and couples gathered to board the ship soon to leave Karachi, along with their animals and coolies. On the deck, the ship’s bearers have lined up to welcome them on board.

Image source: http://www.oldindianphotos.in/2015/03/boarding-ship-at-karachi-c1905.html (viewed on November 27, 2016)

Wrote Tekchand Karamchand Mirchandani, at the end of a long career in Sindhwork:

A large population of English had congregated in Egypt and the Straits Settlements. So Bhai Pohoomull set sail for Egypt and Bhai Vasiamal for the Straits Settlements. When they touched the ground and found a firm footing, they sent for their salesmen in Bombay and set up offices in these new lands. Others learnt of the pots of gold at the end of the rainbow and trade prospered, soon spreading all over the world. (Mirchandani 1920)

The Sindhworkis sold their goods, earning both profit and goodwill. From pheriwalas, peddlers who carried samples and walked around trying to find buyers for their goods, they became retailers.

Aden was not just a part of the British Empire it was a part of the Bombay Presidency, and already settled by traders from other parts of India. While the Sindhi traders made a footprint there, they soon expanded to Cairo and then Gibraltar. Tourism was new. People from Europe were sailing off to see the pyramids for themselves, and from Gibraltar they could even get a glimpse of Africa. The Sindhworkis, as citizens of the British Empire, had access to other colonies around the world, and used them as footholds for expansion. From Cairo and Gibraltar they moved on to other parts of Europe and Africa, and from there to South America. Eastwards, with bases already established in Colombo and Calcutta they moved from the Straits Settlements to the Dutch East Indies and on to China and Japan.

One of the many Sindhi-owned stores on Gibraltar’s Main Street. Photographed by Saaz Aggarwal, October 2013

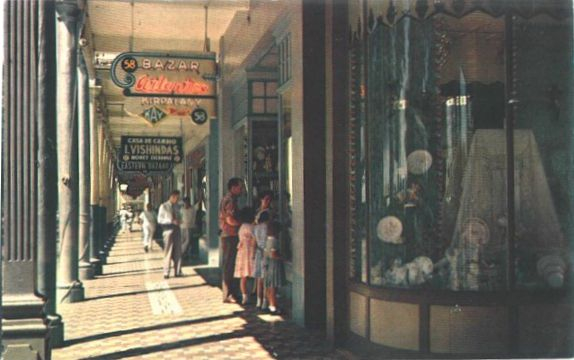

Passengers from scheduled liners looked forward to shopping on the celebrated Front Street of Colon, Panama. In the 1963 photo below are seen shops with Sindhi names, Kriplany and L. Vishindas.

Image source: www.coloncity.com (viewed on November 27, 2016)

Bhojwani promenade in the Central American country of Belize.

Image source: http://edition.channel5belize.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Roundabout0006.jpg (viewed on November 27, 2016)

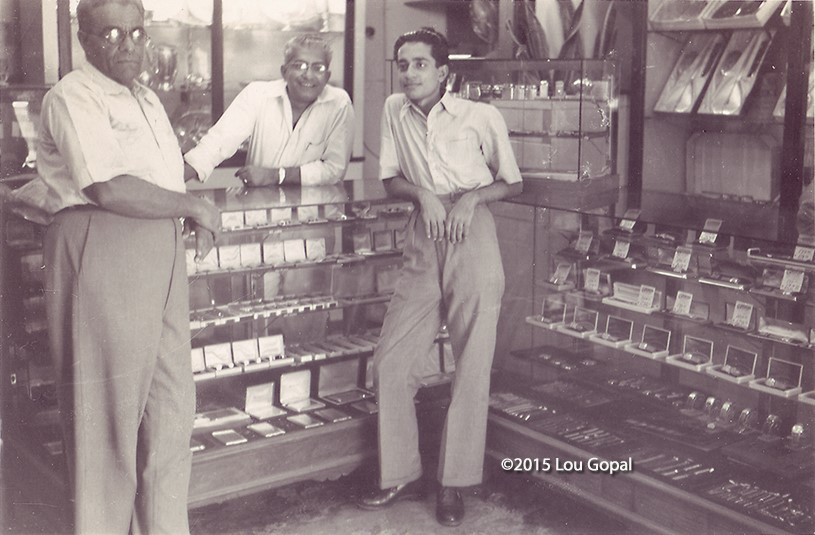

Inside the shop. Lou Gopal’s father, Gopal, in centre, and uncle Kishin on the right. Image source: www.manilanostalgia.com. © Lou Gopal

Pohoomull and Wassiamal Assomull were soon followed by Dhanamal Chellaram, J.T. Chanrai, M. Dialdas, J. Kimatrai, K.A.J. Chotirmall. More followed. As each port became saturated with Sindhi businesses, the adventurous ones went on to the next port and set up shop there. As early as 1907, the first Sindhworki had arrived in Punta Arenas, Chile, one of the southernmost cities in the world.

Ramayana, the store in Punta Arenas, Chile. Photographed by Saaz Aggarwal, June 2015

The Hindu temple occupies a prime piece of sea-facing real estate in Punta Arenas. Photographed by Saaz Aggarwal, June 2015

The expansion continued, and in each new location they settled into a regular trade, moving beyond Sindhwork to products the local markets called for. Many specialized in curios, catering specifically to the tourist trade in the ports where they were settled. Falzon writes of their expertise in the popular Maltese lace, and Markovits describes a ‘new trend, by which some Indian merchants became "global" middlemen, using India as a resource base to raise capital and expertise, but trading in goods which were not produced in India itself' (Markovits 2000).

This coat was imported and sold by Pohoomull Bros. establishment (with a Pohoomull tag) on the grounds of the Old Winter Palace Hotel in Luxor, Egypt.

Image source: https://thevintagetraveler.wordpress.com/tag/pohoomull-brothers/ (viewed on November 27, 2016).

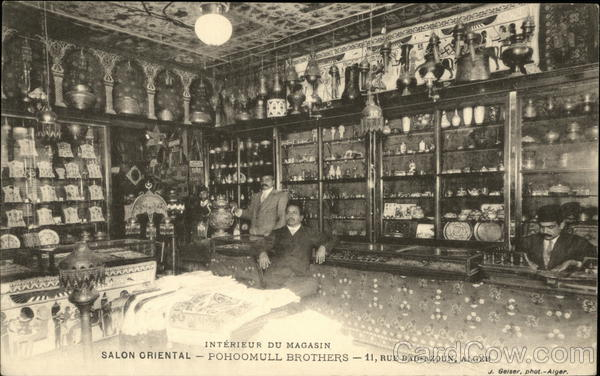

Interior of the Pohoomull Bros store, Oriental Salon, 11, Rue Bab-Azoun, Alger, Algeria, c. 1900s.

Image source: CardCow Vintage postcards (photographer J. Geiser); online at https://www.cardcow.com/468825/oriental-salon-pohoomull-brothers-algiers-africa/ (viewed on November 27, 2016)

In 1925–26, the American writer Jessie Fauset spent six months travelling across France and Algiers. One day, she and the artist in her group stumbled upon a shop on Rue Bab-Azoun. She wrote:

The Pohoomull Brothers greet us cordially; they call us 'friends'; they order for us sweet, black Turkish coffee and Turkish cigarettes. They are delighted to show us a brooch in pearls and sapphires at 3000 francs, and minute and useless souvenirs at three. The more talkative partner leads us to a store-room of brasses and coppers; finely carved trays and vases; gorgeous incense burners; chimes, tables inlaid with copper and silver, cunning and unusual patterns wrought on knives and jugs and utensils whose uses we do not know. We assure him again and again that we have no intention of buying, that we are really quite poor. But he insists that it is a pleasure to him, that we are his 'friends,' that something in the shape of our heads makes him recognize kindred spirits and that therefore he would do for us what he would do for few others: show us in detail his 3,000,000 francs worth of merchandise and count it time well spent. (Fauset 2015)

The global merchants of Sindh had access to finance through personal networks back at home: many members of the community were moneylenders looking for reliable ventures in which to invest. As these early capitalists secured their locations across the globe, their headquarters continued to be in the Shahibazar locality of Hyderabad.

Present-day Shahibazar. Some buildings carry traces of their pre-Partition owners. The newly-painted building with ‘Lachu Lodge 1940’ in front carries a heavy and rather poignant story: the Lachu, for whom it was named, would have had it for just seven years. And yet, 70 years later, the present owner continues to honour his memory. Photo courtesy: Mohsin Joyo and Akhtar Hafeez

The Hindu Swastik symbol and ‘Vande Mataram’ written in Sindhi are clearly visible. Photo courtesy: Mohsin Joyo and Akhtar Hafeez

The Hindu shopkeeper

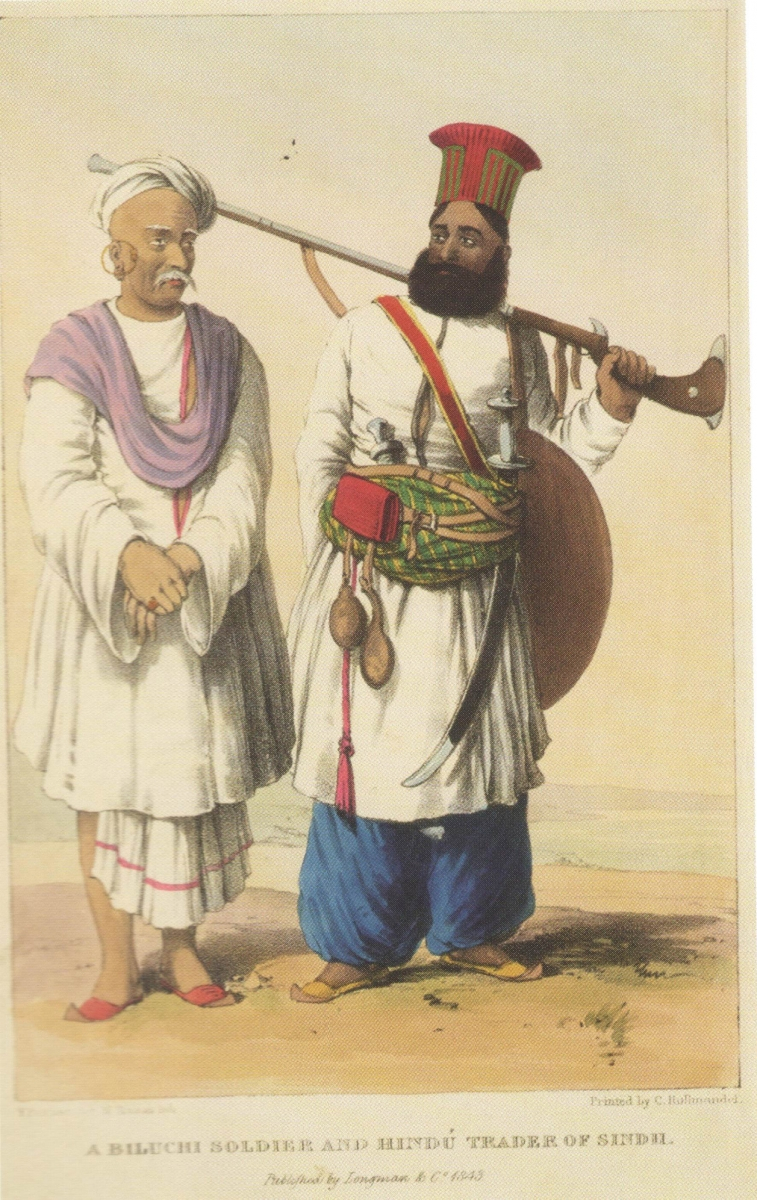

A Biluchi Soldier and Hindu Trader of Sindh. Source: Frontispiece to Personal Observations on Sindh by Thomas Postans (1843). Courtesy: www.archive.org

Most of the shopkeepers of Sindh were Hindu banias. They provided an essential service to the village community, a role which extended from selling grocery and staple supplies to providing money advances and loans when required.

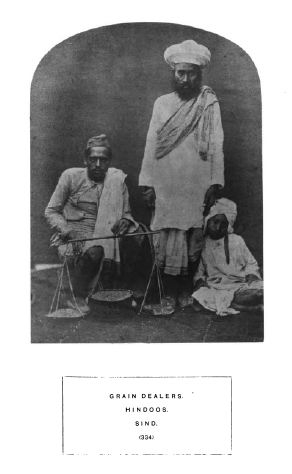

Grain dealer. Image source: People of India, volume 6. Courtesy www.archive.org

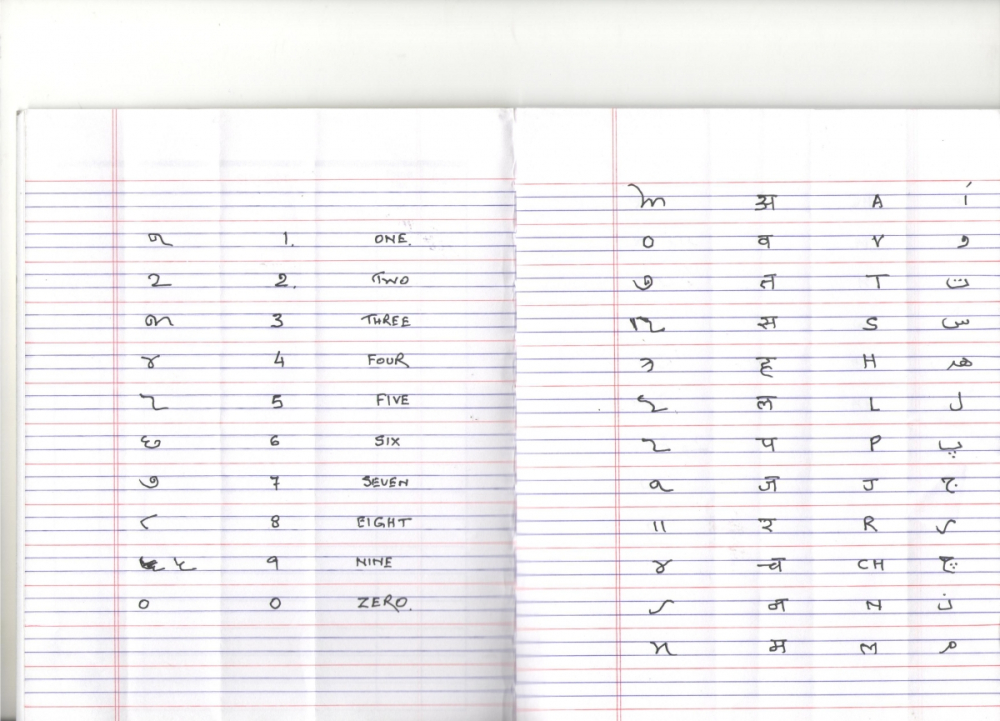

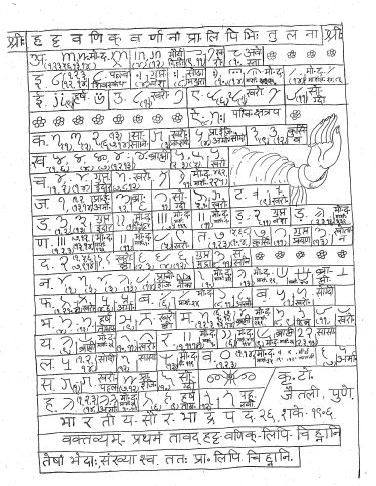

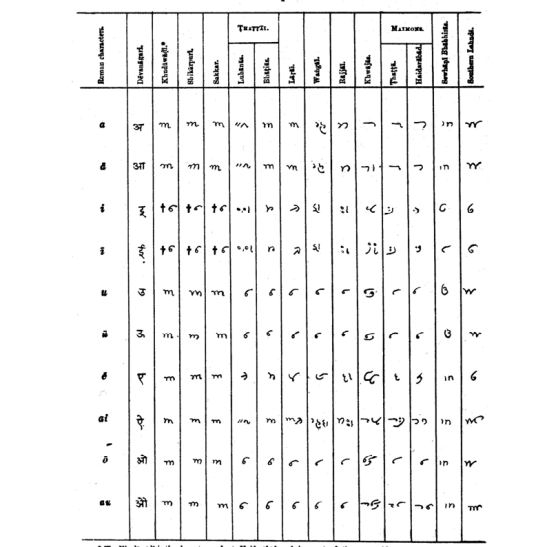

By tradition, their sons would not have been sent to school but they were inducted into business very young. They were trained in accounts and mental arithmetic and in terms of writing, they were given instruction in Hatvanaki, a traditional script of Sindh (Hatvania means ‘small trader’). While some sources such as Mark Anthony Falzon describe it as Hatta Varnka, the secret script of Sindhi traders, other thinkers link it to older scripts of Sindhi.

Hatvanaki alphabets inscribed from memory by Chimanlal Dabla, who learnt it from his father as a child c. 1940s.

Chart of Hatvanaki alphabets in Jetley (1985), sourced by Devendra Kodwani

Some scripts of Sindh. Image source: https://hindusofsindh.wordpress.com/2013/06/06/forgotten-sindhi-script-waranki/

While the Perso-Arabic Sindhi script used in Sindh and in many parts of India today was given its formal character in an exercise by the British colonials (Matthew A. Cook describes this process in his talk), the Bhaibands continued to use their traditional script, as it was a convenient way to keep accounts and send messages that nosy tax collectors could not decipher. There was yet another language used in Sindh, and that was Gurmukhi, the language in which the Guru Granth Sahib was written. Many women of 19th and 20th century Sindh learnt it at home from their mothers and mothers-in-law so that they could read the scriptures and this enabled them to write when they needed to. Almost no modern-day Hindu Sindhis learn these languages any more.

In Sindh, where Hindus were a minority (unlike in most parts of India), a century under the divide-and-rule policy of the British empire had created a certain degree of polarization. British concentration on urban education and the withdrawal of support from traditional Muslim education caused divisions of status and opportunity. In rural Sindh, the Hindu moneylender, who owed at least part of his prosperity to the indebtedness of the Sindhi Muslim, laid the ground for a characterization of Hindus as scheming and exploitative (Kothari 2007).

It was a complex situation, and some aspects of this complexity emerge in the two following examples. Historian Hamida Khuhro writes, in her biography of her father Mohammed Ayub Khuhro:

The ordinary villagers who came to the small town bazaars for their everyday needs, clothes, agricultural implements and so on, were treated with contempt by the shopkeepers who were invariably Hindu banias. They were quite willing to sell to the villagers but would jeer at their clothes, their accents and their poverty. If they asked for water in the heat of the sub-continental summer it would be given to them not even in an earthenware cup but would be poured out into their cupped hands. The general term which the Hindus would use to refer to the Muslims was jat which colloquially meant a mixture of illiterate and uncouth. (Khuhro 2000)

This vivid and doubtless accurate description is enhanced through a sensitively described incident from another biography. Muhammad Hussain Panhwar (Dec 25, 1925 – Apr 21, 2007), grew up in a traditional agricultural family and rose to a position of prominence. In his story ‘The Hindu Village Shopkeeper and Interest’, he writes about a day in November 1933 when he was sitting with his grandfather and father as they settled accounts with the village shopkeeper. With a large family—ten daughters and two sons—and just two-and-a-half acres of land, it was a meagre living. Until the Sukkur Barrage was built, canals from the Indus flowed directly into the fields. The farmers of Sindh would spend three months of the year in the arduous task of clearing silt from their fields. ‘Two out of five crops would normally fail and every farmer was in debt,’ wrote Panhwar.

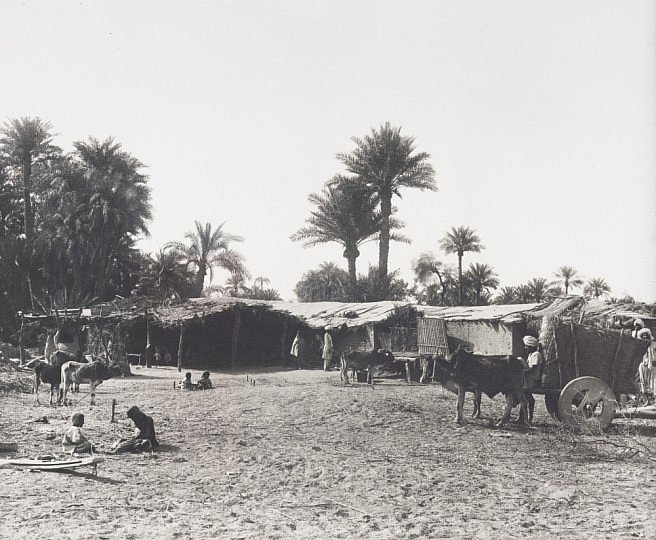

Farm in Sindh (photographer Fred Bremner, 1890). Image source: National Galleries Scotland (CCBY-NC)

Online at https://art.nationalgalleries.org/sites/default/files/styles/postcard/public/externals/94214.jpg?itok=EQLzJukn (viewed on November 27, 2016)

That day, the eight-year-old Muhammad Hussain sat on the floor between the two cots the adults were sitting on, and listened. When he heard numbers discussed which he knew to be inaccurate, and whispered his calculations to his grandfather, the bania smiled with appreciation for the child’s intelligence and offered to teach him book-keeping. He writes:

Next day my father sent me to his shop, where his son Rupomal taught me Hatki (shopkeeper’s script). When I went to high school the same Hindu advanced my father a loan for my education and without this I would not have been able to pass even matriculation examination or High School graduation. My education did not frighten him at all… His father Lilo Mal was partner of my maternal grandfather for years. So much was the faith and trust of my maternal grandfather in him, that finding that his young bride did not know cooking, he asked Lilo Mal to help and he did help her to become the best cook among all neighbouring villages.

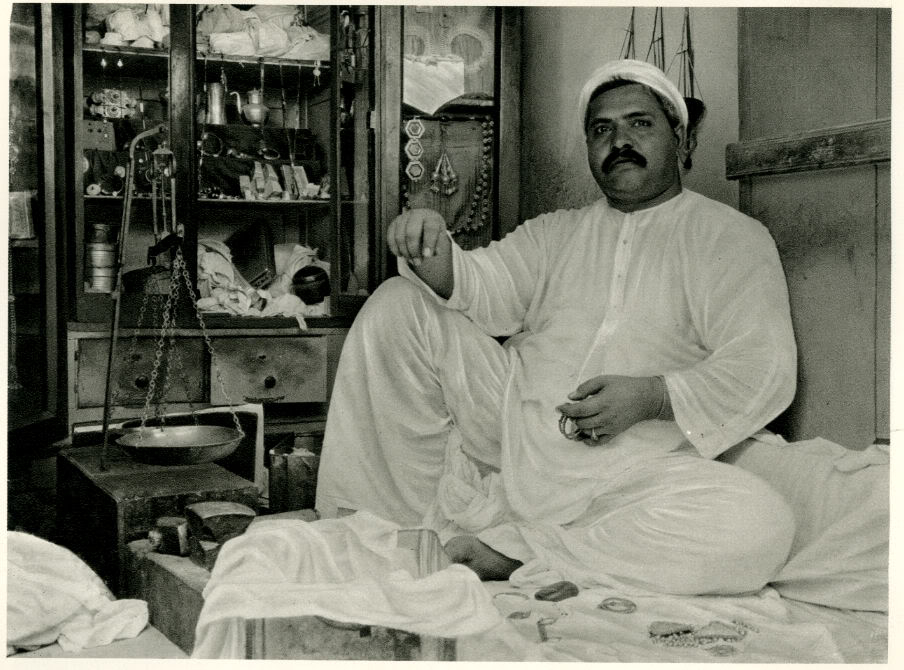

Portrait of a jeweler in his shop in Hyderabad c. 1928. Image source: http://www.oldindianphotos.in/2011/10/portrait-of-jeweler-in-his-shop-in.html (viewed on November 27, 2016)

The Hindu trading community for their part kept aloof, lived frugally and would whisper amongst themselves: 'Jaye mathan jaye; joye mathan joye' which could be interpreted to mean that when a Hindu had money he would build more and more houses; when a Muslim had money, he would marry more and more wives.

It was the simple traders and grain merchants who earned and saved and rose to affluence and became money lenders, bankers and financiers. Between these two ends of the Bhaiband spectrum, it was a group of individuals, neither poor nor wealthy (Falzon 2004) but definitely daring and ambitious, who first set out on Sindhwork and laid the base for today’s diaspora.

Naomul’s role

The British East India Company had its eye on Sindh for many years, but its rulers, the Talpur Mirs, were wary. One of the Company’s most lucrative products was opium, which was cultivated in Bengal and sold in China. But alternative opium plantations had come up in Malwa and it was being smuggled to China via Rajasthan and Sindh. Possession of Sindh would help curb this upstart competition. Sindh was also attractive for Shikarpur, historically a gateway to Kabul, an important position in what the British called the Great Game of strategy between their empire and the Russian empire. The commercial possibilities of the Sindhu River were another draw (Aggarwal 2012).

In 1837, when the Mirs reluctantly gave permission for a survey of the sea coast of Sindh and the delta of the Indus, Captain Carless of the Indian Navy received supplies and information from a Sindhi businessman based in Karachi. His name was Naomul Hotchand. The useful service Naomul provided earned him the trust of the British and gave him the opportunity to expand his business. It was a relationship that benefitted both. For Naomul the direct benefit may have been simply to continue enhancing trade, but the British imperialists had political motives and when the time came for them to invade and annex Sindh, it was Naomul who is said to have opened the doors and held them open until the deed was done.

‘Seth Naomul is undoubtedly an extremely interesting personality,’ writes Hamida Khuhro in the introduction to a reprint of Naomul Hotchand’s memoirs (made for private circulation by some of his descendants, a branch of the Bhojwani family). While Khuhro has reason to doubt some of what Naomul claims in his memoirs, she concedes that, ‘He is farsighted, shrewd and resourceful. His Memoirs have a historical importance for a number of different reasons.’

In the Memoirs, Naomul writes of his 16th-century ancestor, Seth Bhojoomal, whose business traded across the Persian Gulf countries as well as into Central Asia. When his town Kharrakbandar began to succumb to the silting it was prone to, Seth Bhojoomal worked to develop a new seaport: Karachi. Some of what Naomul claims may be discounted, but while Khuhro is of the view that Naomul was a traitor who betrayed Sindh, Matthew A. Cook disagrees, explaining his reasons in his talk. In his introduction to a copy of the Memoirs, he writes: ‘Like most Hindu merchants from Sindh, Naomul was a practical and astute man. These characteristics earned him a great number of business contacts. Instead of an anti-nationalistic force, the British were initially just a powerful new name in Naomul’s already impressive book of contacts.’

Hyderabad

Hyderabad, unlike Thatta and Shikarpur, was not on the international trade routes. However, the rulers of Sindh, whom the British had overthrown, were connoisseurs of art and craft. Writes Falzon:

Travellers’ accounts of Sind from the first half of the 19th century invariably remark on the splendour of the court of the Talpur Mirs. Even allowing for a certain degree of exaggeration owing to the enchantment of British travellers encountering a family of ‘Oriental princes’, it is clear that the Mirs spent much of their money not on the building of palaces or the strengthening of the army, but on the purchase of objects of beauty and rich craftsmanship. James Burnes, who visited the Court in 1819, was in awe at the Mirs’ wealth: their richly-embroidered textiles, jewels, and the enamelled firearms they used on their hunting trips (Burnes 1831). An indication of the Mirs’ appetite for fine craftsmanship are the contents of some of the booty taken by the British in 1843. (Falzon 2004)

It was with their patronage that the craftsmen of Sindh flourished and this led to the opportunity that the Bhaibands of Hyderabad extended to start trading around the globe.

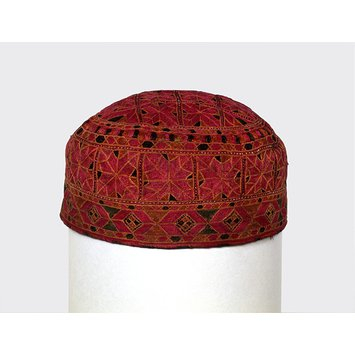

British writers and administrators of the empire have described the bazars of Hyderabad eloquently. With a mix of people from different provinces, they were colourful, dusty places in which many languages could be heard and many different types of pagris (turbans) were seen, interspersed with heads covered in the traditional embroidered Sindhi topi (cap), and the black cylindrical hat adopted by the Amils.

Sindhi cap, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. ‘Probably worn under a turban, this cap is embroidered in the delicate chain stitch found on women's dresses in the area’ (Crill 1985)

Image source: Collections, V & A Museum (viewed on November 27, 2016)

Topi of brocaded silk on a cardboard base, mid-19th century © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. ‘Known as "Sindhi topi" or "serai topi", these unusual hats were usually made in brightly coloured velvets or flamboyant brocades, as here, always with the contrasting panels at centre back and front of the drum. They were worn throughout the 19th century by Muslims in Sind. Originally monopolised by government officials and lawyers, the style also filtered down to other classes of society' (Crill 1985).. Image source: Collections, V & A Museum (viewed on November 27, 2016)

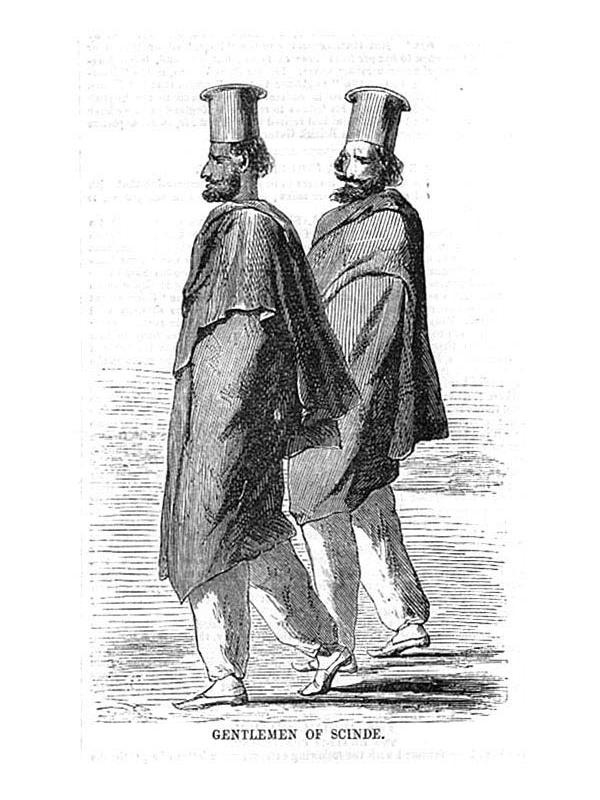

Gentlemen of Scinde (Sindh), 1857. Image source: https://c8.staticflickr.com/9/8381/8650596143_08e5e525dc_c.jpg (viewed on November 27, 2016)

The above image first appeared in The Illustrated Times, London on July 25, 1857 with accompanying text:

SCINDIAN NOBLEMEN - Our engraving represents a couple of Scindian noblemen. The people of Scinde are partly Hindus, partly Beloochee, and Mahomedans; and, until the year 1844, the country was governed by the Ameers, who exercised an aristocratic military despotism. Their power was, however, completely broken by Sir Charles Napier, and Scinde is now a British dependency. The nobles delight in the chase, and much of the country was depopulated by them for hunting grounds. The jungles around Hyderabad swarm with tigers, wolves and hyenas, as do the pools with alligators, and other formidable reptiles. The Scindians are simple in their dress, which in the hot season consists of a pair of loose muslin trousers and short tunic. Their head dress is peculiar; it is made of a species of cardboard and is painted, or covered with cloth. Over the tunic, when in the open air, they wear—no matter how sultry—a thick kind of shawl, which they throw around them very much in the style in which the Spaniard wears his cloak.

The merchant population of Hyderabad included a wide spectrum, from the seller of grain to the merchant with a conglomerate of different interests, like Naomul and his peers.

What British writers described as ‘a town of mud huts’ was soon developed into a cantonment. In 1853, the Hyderabad Municipality was established and civic infrastructure came up. In 1876, Richard Burton made a second trip through Hyderabad and reported, ‘The improvements are the disappearance of many pent-roofed hovels, and the exchange of dark, narrow, dusty or muddy alleys for broad streets, which, however, catch the sun and harbour the wind’ (Burton 1877:253).

Soon enough, mansions sprang up on the broad streets. Money came in to Hyderabad from the Sindhworkis and it was used to give their families back home a life of luxury.

A unique lifestyle, sustained over generations

Young men from the Bhaiband families of this community would go to work by the time they were 15 or 16 years old; sometimes even sooner. It was a hard life, as Tulsi Mohinani describes in his article, ‘My Ordinary Life: Seventy Years and Five Continents’. They would invariably live above the store in an apartment shared by other employees of the company, who were also Hindu Sindhis from Hyderabad. They worked all day with little or no social life and were quite often mercilessly exploited by their capitalist bosses who preferred them to stay uneducated and unaware of their rights, and encouraged them to take recourse in alcohol, as T.K.M. Mirchandani notes.

The employees worked in the foreign countries for two to three years at a time, during which their expenses were taken care of and their salaries were paid directly to their families in Hyderabad. At the end of the contract, a period known as musafri, they went back home on a break of a few months. Most young men returning after their first musafri would now enter into a marriage arranged by the family. At the end of the two or three month holiday, he would go back to work either with the same company or another, possibly in another country. By the time he came back on his next home visit, his first child would be a few years old and often enough it would be the first meeting between father and child. This routine continued until the man retired at around the age of 40, and returned to settle in Hyderabad. By that time, many would have branched out from the firms they had worked in and started businesses of their own, which they would now leave to their sons. They would also employ other young men from Hyderabad.

There were cases of Bhaiband men who married local wives and settled in the faraway lands; some maintained families in both places. But by and large the international communities comprised of groups of men who adapted to new languages and new cultures but were careful to retain the culture and family values of their homeland. Their families back in Sindh comprised mostly women, children and the family elders, who with the money remitted from overseas lived a comfortable life. It is estimated that, by the 1940s (when the price of ten grams of gold was still well below Rs 100) the annual stream of wealth coming in to Sindh from the Bhaibands was between five and ten crores of rupees (Dialdas 1951). All these events had their influence on family life in the diaspora.

Shaped by historical forces

During the years of the Second World War, the sea routes closed and families were separated for as long as seven years. Both Monica Bhojwani and Tusli Mohinani speak of this experience. After the war, it became clear that the struggle for Indian independence was coming to fruition. Sindh was, in fact, a hotbed of the Indian freedom movement. The 1942 ‘Quit India’ call by Gandhi filled the jails, as it did all over the country. But the situation in Sindh was complex and for various reasons, the government declared Martial Law in the province.

Some Bhaibands, inspired by Gandhi’s call for Swadeshi and to boycott foreign products, threw their imported fabrics into bonfires and set up khadi stores, which naturally did not give them the kind of margins they were used to and these businesses declined, consigning them to unsung martyrdom. Many Bhaibands contributed to the funds of the Indian National Congress. Bhai Pratap was one of them and he also played a committed personal role in the campaign to spread awareness and create a nationalistic spirit, as can be seen in the article ‘Bhai Pratap: A Tribute to a Forgotten Hero’.

Demonstrating women in Karachi pay homage to the national flag, c. 1931: an unusual sight. Image source: Archive 150 on Facebook

When Partition was announced, it was clear that nothing would ever be the same again. However, nobody foresaw the violence and many Bhaiband families stayed on for a few months after Partition, escaping with their lives as the situation became increasingly dangerous. In many families the men had returned to their global outposts and the women were left to travel on their own, mostly fleeing by train from Hyderabad with their children and elders. Nobody knows the kind of hardships they faced because there are no records of those traumatic journeys. They did not talk about what happened to them.

The Bhaiband families of Sindh were used to a three-point existence: their places of business in some part of the world; Hyderabad where their families lived; and Karachi, the port from where they sailed and from where their goods were dispatched or received. After Partition, the Hyderabad–Karachi section of this triangle shifted to Poona–Bombay. Many Bhaiband men bought property and settled their families there, some preferring Poona for its lower real estate costs and as a cleaner, greener, less crowded place away from the big-city vices.

In the years following Partition, the foundation that had been established by the early pioneers gave a base to the displaced ones. Families sent their young sons out to these outposts all around the world. They followed in the footsteps of the ones who had gone before, working hard, depriving themselves, sending money home, and (some sooner than others) starting their own businesses which, over the years, grew more and more prosperous. Often enough, they were displaced yet again by global politics and economics.

In the 1950s, events in Vietnam sent them out to Thailand and Laos. In the 1960s, their stronghold in Indonesia loosened and Hong Kong opened up. Spain sealed the border with Gibraltar in 1969, forcing economic hardship on the British colony and its Sindhi settlers. In the early 1970s, some of the African countries turned hostile and ejected Indians or restricted them by insisting they take local partners or by imposing restrictive quotas. Sindhi families moved from Cairo to Alexandria. Many found new homes in Malaga and other areas of inland Spain. The Sindhis of Vietnam quit after the war and settled in Cambodia, some moving on to Laos. In the mid-1970s, the Chilean government leaning to Communism was violently overthrown by a military dictator who stepped in with free-market measures of boosting the Chilean economy, creating free-trade zones. In came the Sindhis. And the story goes on.

Dubai: Before and After. In the first photo, taken in 1966, the building housing the British Political Agency can be seen. It is visible in the 2005 photo too, now the British Embassy. The desert that once lay beyond has been transformed to a bustling area of businesses, restaurants and homes. Civic expansion continues. As with the other places in which Sindhis settled, their enterprise and commercial skill fuelled the development of their adopted homes. Photographer Narain R. Sawlani. The image first appeared in Dubai Creek published by Explorer Publishing & Distribution 2005. © Narain Sawlani

A few clarifications

Spelling of Sindh: Sindh was first spelt in English variously as Scinde, Sinde, and sometimes even Sindy. It settled into ‘Sind’ and remained so until 1990 when the official spelling was declared to be Sindh. Some publishers determinedly stick to the colonial spelling Sind. The correct spelling, Sindh, is used here, and replaces ‘Sind’ in some quoted text.

The city of Hyderabad, central to this topic, belongs to the province of Sindh which was given in toto to Pakistan when India was partitioned in 1947. India once had two Hyderabads and they were distinguished by referring them to as Hyderabad, Sindh, or Hyderabad, Deccan. Here Hyderabad, Sindh is referred to as just Hyderabad purely for the purpose of editorial hygiene.

Sindhwork is a word that came out of the British colonization of Sindh. Peddlers selling curios were asked by potential British customers, 'Is this made in Sindh?' to which they naturally replied, 'Yes'. Having learnt that things made in Sindh were attractive to them, they would start by asking, 'Do you want to see Sindh work?' These door-to-door salesmen were dubbed Sindhworkis. The name stuck (Mirchandani 1920).

Bhaiband is derived from the Sindhi word bha, which means brother; Bhaiband once signified the brotherhood that does business together. Over time, it came to represent the community. In Sindh, the Hindus did not have the rigid caste system of the rest of India. The elite of Hyderabad in the 1940s comprised two main communities, the Amils and the Bhaibands. The Amils generally took to education and professional working life; the Bhaibands generally took up trade, worked in their own family business, or joined one of the Bhaiband trading houses and became Sindhworkis. In modern India, the title Bhai tends to have a flavour of Bollywood-inspired association with the Bombay underworld. However, in the heyday of Sindhwork, Bhai was an elder brother, someone you loved, respected and could always rely on.

Thank yous

For the introduction to this subject and for their support through two years of research, for many original ideas and much Sindhi hospitality, I’m grateful to Sanjay and Tulsi Mohinani and members of the Mohinani family; for specific inputs to Tom Chandy, Matthew A. Cook, Chimanlal Dabla, Mohsin Joyo, Saloni Kapur, Aslam Khwaja, Devendra Kodwani, Gul Metlo, Neha Pande, Mehtab Ali Shah, Amrita Shodhan and Dharmendra Tolani.

References

Advani, A.B. 1934. 'The Early British Traders in Sindh', in The Journal of the Sindh Historical Society 1:43.

Aggarwal, Saaz. 2012. Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland. Pune: Black-and-white fountain.

———. 2016 'The Bhaiband Network: Sindhi Multinationals in the Nineteenth Century', 'Heritage India Keepsake Collection', issue 1.

Burton, Richard F. 1877. Sind Revisited. London: Richard Bentley and Son.

Cook, Matthew A. 2016. Annexation and the Unhappy Valley: The Historical Anthropology of Sindh’s Colonization. Leiden & Boston: Brill.

Crill, Rosemary. 1985. Hats from India. London: V & A Museum.

Dialdas, Bhai Pratap. 1951. Gandhidham: its Historyand Implications. Gandhidham, Bombay: Sindhu Resettlement Corporation Ltd.

Falzon, Mark Anthony. 2004. Cosmopolitan Connections: The Sindhi Diaspora 1860–2000. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill N.V.

Fauset, Jessie. 2015 [1925]. 'Dark Algiers the White', in The Wiley Blackwell Anthology of African American Literature, vol. 2, edited by Gene Andrew Jarrett. Boston: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Hiranandani, Popati. 1980. Sindhis the Scattered Treasure. Mumbai: Malaah Publications

Hotchand, Seth Naomul. 1915. Memoirs of Seth Naomi Hotchand C.S.I. of Karachi 1804–1878, trans. Rao Bahadur Alumal Trikamdas; ed. Evan James, Commissioner in Sind. Exeter: William Pollard & Co.

Hughes, A.W. 1876. A Gazetteer of the Province of Sindh. London: George Bell and Sons.

Husain, Rumana. 2010. Karachiwala: A Subcontinent within a City. Karachi: Jaal.

Jetley, Kishinchand. 1985. The Date of Sindhi (Hata Vanika) Script and the Need to Propagate it! Pune: Akhil Bharatiya Sindhi Sahity Vidvat Parishad.

Khuhro, Hamida. 2000. Mohammed Ayub Khuhro: A Life of Courage in Politics. Karachi: Oxford University Press Pakistan.

Kothari, Rita. 2007. The Burden of Refuge. Hyderabad: Orient Longman.

Markovits, Claude. 1999. Indian Merchant Networks outside India in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A Preliminary Survey. Modern Asian Studies 33.4:883–911.

———. 2000. The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947 Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Mirchandani, Tekchand Karamchand. 1920. Sindhwork and Sindhworkis. Hyderabad.

Polo, Marco. 2014 [1920]. The Travels of Marco Polo, trans. Henry Yule, rev. Henri Cordier. London: John Murray. Online at https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/p/polo/marco/travels/complete.html (viewed on January 25, 2017).

Watson, Forbes J. and Kaye, Sir John William. 1872. The People of India. Photographic Illustrations of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan, vol. 6. London: The Government of India.