From the early modern period till this day, the Sindhis continue to be one of the imperative, dynamic, mercantile communities whose diasporic wings are spread far and wide. Claude Markovits’ seminal work (2001) on the merchants of Sindh from Bukhara to Panama analyses in depth the financial strength of the Sindhi capitalists and merchants in significantly influencing the economy of diverse ports across the globe. Though not much has been written about their presence in the region of the Persian Gulf, their role in the economic life of the Gulf was indeed robust and vibrant.

The Sindhi merchants in the Persian Gulf chiefly originated from Shikarpur, Thatta and Sukkur, among other regions of Sindh, and they were primarily from among the commercial communities of the Bhatias and Khojas. Without further analysis of the ethnographic profile of these trading communities, this brief study seeks to portray the significant commercial presence of the Sindhis in the Persian Gulf. In recognising their mercantile role, an overview of their prevalence and trading operations in the Persian Gulf is mapped. The study describes how their mercantile capital investments in the pearl trade infused their growth.

Backdrop

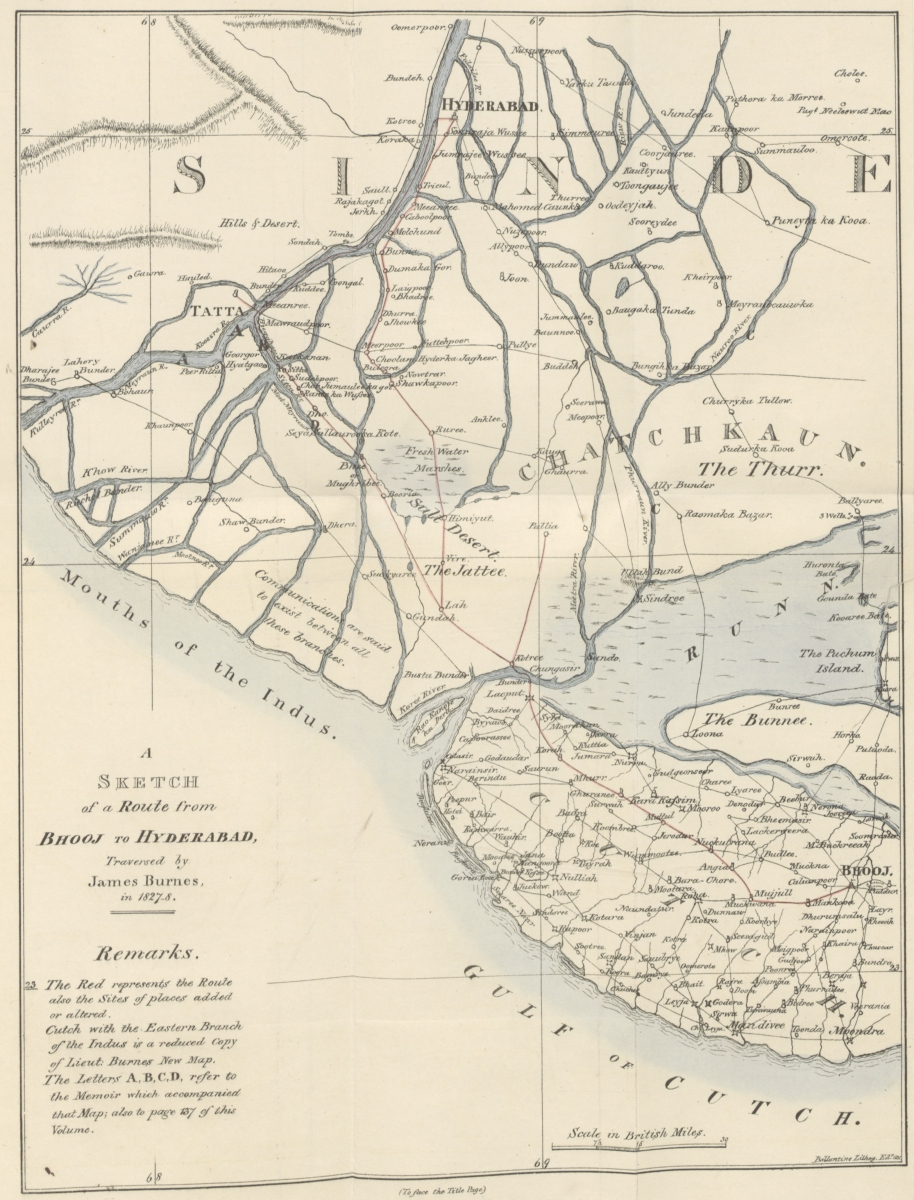

In the 18th century, the agrarian resources of the Sindh region empowered its participation in maritime trade across the Indian Ocean. In particular, rice and other grains of different varieties strengthened Sindh’s mercantile mobility. Some of the neighbouring regions of the Gulf of Kachchh, clouded by their arid geographies, were compelled to import grain and other staples from Sindh. These essential imports supported a local populace which was engulfed in a state of deprivation, and this led to the formation of a complex inter-regional trade network. The trade between Kachchh and Sindh was carried out through Lakhpat, Jakhau, Mandvi, Mundra and Anjar on one side and on the other through Maghribi, Shahbandar, Gorabari, Karachi and formerly through Darajee.

Sindh and Kachchh 1827 map. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sindh_and_Kutch_1827_map.jpg

Lakhpat, situated at the north-western extremity of Kachchh, was the major port for the introduction of goods into Sindh. Other than regular trading, Lakhpat was an important transit port. The passenger ferry to Sindh via the Lakhpat water channel served as an imperative revenue-earning route. The Rao of Kachchh fixed a charge of one Kori per head for the passenger ferry, and this gave the people of Lakhpat their chief source of income. It is not surprising that in the late 18th century, there were around 250 Sindhi merchants living in Lakhpat. Another old land route that connected Sindh was through Lakhpat via the Rann of Kachchh and Badina (Sampat 1935:31, 32).

Lieutenant Leech’s report on the trade of Mandvi in the 1830s provides a comprehensive list of commodities exchanged between Sindh and Kachchh. The following paragraph demonstrates how mundane and staple commodities powered the inter-coastal trade between Sindh, Kachchh, Malabar and Bombay:

The exports of Sindh to Kachchh are white and red rice, bajree occasionally good (jaggery), huldee (turmeric), pabadee (lotus seed) and salt fish. From Mandvee to Luckpat are exported iron, steel, tin, sugar, rice from Malabar called Jirasar, Sooparees, Sindaree coir ropes, Sindar, cocoanuts, katrot, wooden basins, khajoors, khariks, teakwood, rafters and bamboos, Musroo cloth cloves, cardamoms, dalchiny, kabachiny, loban, chandan, boxes of silk thread; cloths from Malabar, as sela, pikrkara, dupta, chowkdees, white handkerchiefs, Khady Madrasee; also of Bombay cloths the following: Madarpat, Bafta, doree, satin, sail cloth velvet and chintz. (Leech 1837)

From the month of asoo i.e. October, the Kachchh Kotias would steer the course to the coast of Sindh for the following firewoods: Cher Chawar, Krod to Bedeewaree, Phityanee, Wagudar, and Reechal. To secure the most precious cargo of grain, around 150 boats would make three or four trips. Each of the wood-laden boats ‘paid 5¾ rupees to the Sindh Government for cutting the wood, 5 pies to the Meeran Peer and 5 pies to the Sipahis' (Leech 1837).

The outcome of such rich inter-delta, inter-regional and inter-coastal trade was the expansion of commercial links with the neighbouring regions, which also supplied their surplus to the Arabian and Persian Gulf regions. Other than Kanara, Sindh was the main supplier of grain to the Arabian Gulf, on which Muscat principally depended. In the late 16th century, the most profitable trade for the Portuguese casado (the term used for a community developed by the early Portuguese settlers in India, largely comprising the soldiers and artisans who married Indian women and were allowed to leave the royal service and settle down as citizens or traders) was established between Lahari Bandar and Basra, Muscat and Hormuz, on which they made ‘extraordinary profits’. Moco Fidalgo Fernao Sodre Pereira noted in 1696 how he had cruised off Muscat ‘entrusted with the task of preventing that any small ships would cross over from Sindh which was so that no supplies pass into his (the Imama’s) lands’ (Barendse 2009:319). Undoubtedly, the granary of Sindh critically fed the populace of the Gulfs of Kachchh and Arabia.

The prime products of Sindh, thus, ensured the integration of its economy into the Indian Ocean economy, and profitably strengthened the commercial position of the merchants of Sindh in the wider networks. The exposure of Sindh to the demands of the world market in the 18th century caused the reorientation of its regional economy, as well as its society and settlement patterns, towards the specialised production of cotton, pearls, dates, and ivory as well as many more items. The degree of integration, and its impact on the economies of these zones was unprecedented and set into motion a long history of commodity specialization which linked the adjoining regions, and indirectly to more distant markets of the West, through an import-export trade in the specialised products.

There are several parallels between the Shikarpuri, Thattai, Kachchhi and Halari Bhatias who successfully embedded their capital networks in the Indian Ocean credit system. From the 17th century, their trading relations with the Persian Gulf expanded exponentially. The ports connected with the Indus delta and the Gulf of Kachchh regions facilitated their connectivity with the greater Indian Ocean. Sindh’s overland network and Kachchh’s hinterland contacts enriched the mercantile cargoes, which made the commodity exchange trade with the Persian Gulf vibrant and profitable. By the beginning of the 18th century, Shikarpur, Thatta, Hyderabad, Mandvi and Halar, among other ports of the Gulf of Kachchh, were commercially poised to share the fortunes with Surat in the Persian Gulf. Their structured and seasoned mercantile operations earned them an advantage in the mercantile world. More specifically, their tried and tested business system of gumasthas (commercial agents), exchanges in hundi (traditional promissory note) and their commercial structures of bazar (market) and pedhi (a traditional Indian business office where businessmen squat on mattresses on the floor with their account ledgers and samples around them), animatedly highlighted the mercantile milieu of the Persian Gulf.

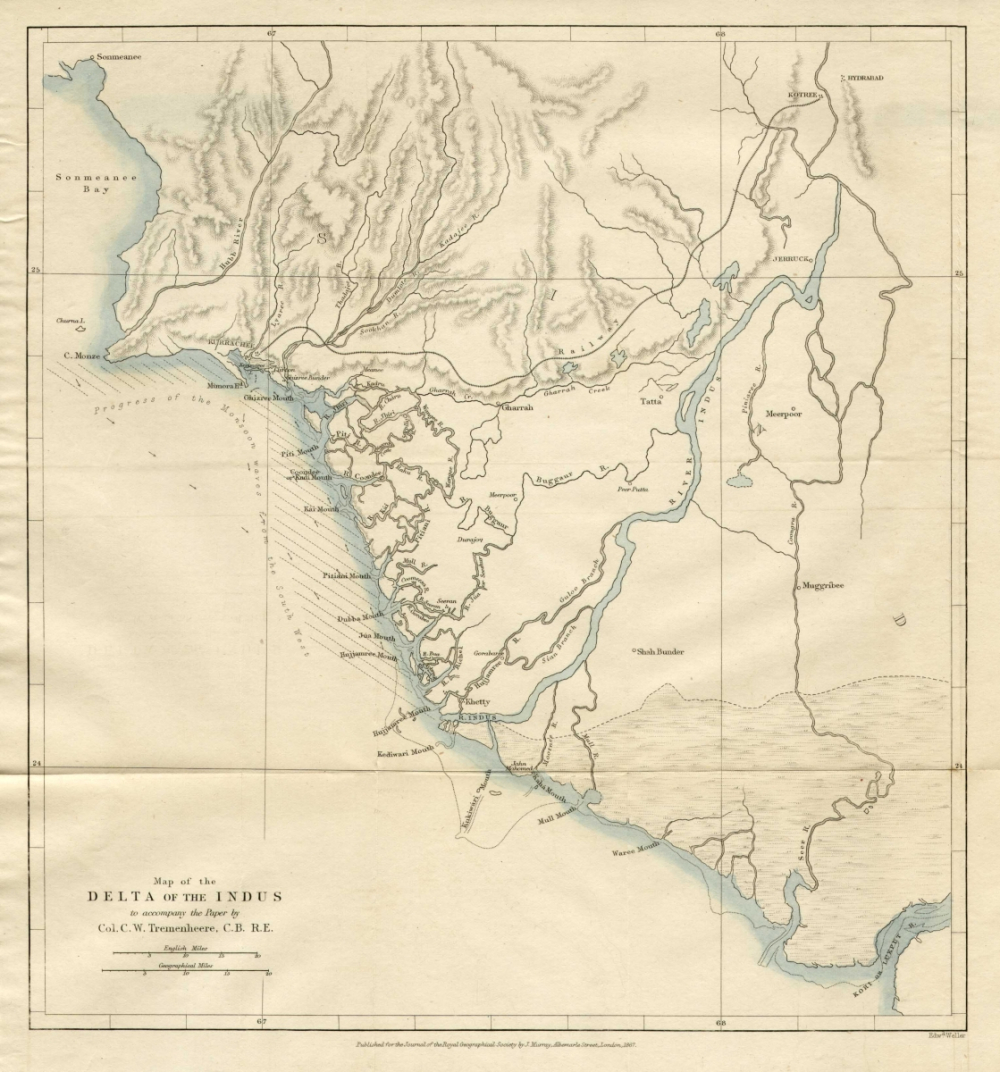

The early presence of Sindhi merchants in Muscat

During the Portuguese settlement of Muscat, the tradesmen from western India, especially from Sindh, were active in commerce. One of the ports of Sindh, Vikkur, had considerable trade and was a depot for the larger part of the foreign and internal commerce of the Indus Delta. The average number of boats that annually sailed from it with full cargoes was about 400: of these ten were sent from Bombay, three from Muscat, nine or ten from the Makran coast and the remainder from Kachchh and Gujarat. Muscat cargoes to Vikkur contained ‘dates, slaves, dried fruits and pomegranate rinds’ (Carless 1837:470–71). Another place which was commercially linked to Muscat was Thatta. The Bhatias of Thatta, from the late 15th century to the early 19th century, formed the bulk of the huge Indian trading community in Muscat (Markovits 1999:900). Some of these merchants acted as supply agents for the Portuguese force in the 17th century.

1867 Delta map of the Indus. Source: http://pahar.in/

Among the earliest pieces of evidence which indicates an Indian presence in Muscat appears in a tale of Indian traders in the accounts of Ibn Ruzaiq.[1] The early settlement and influence of the traders from western India in Muscat, and the reciprocal relationship between the merchants and the ruler, worked to successfully expand the trading network. In 1939, Sampat attested this point by noting that in Muscat and the Persian Gulf ports, the Kachchh-Kathiawar merchants had established colonies for some 250 years, and that their sea routes to those regions of the Gulf were connected through the ports of Sindh. He adds that the trading relations too were ‘very old’ (Sampat 1939).

Following Oman’s successful expulsion of the Portuguese in 1649 and their exit from Mombasa half a century later, Oman’s powerful fleet controlled the sea lanes of the Arabian Sea. These political developments brought a plethora of changes in the Arabian Gulf politics and also redrew the layout of the trading network of the Gulf. Under Yarubi rule, Muscat merchants found further expansion of their trading activities with India, Yemen, Africa and the Persian Gulf. Most importantly, the rising control over the Gulf politics and economy opened many opportunities for Muscat, where the Basra trading links with around six major trading areas, including India, proved to be advantageous. The Tigris and Euphrates provided the highways for Basra’s trade with Baghdad and points north, such as Aleppo, while southern Persia was reached either through caravans or the Karun River. Lastly, Basra traded extensively with other ports on the Persian Gulf (Abdullah 2001, p. 57). Undoubtedly, by the 18th century, Basra’s maritime trade with Surat and later with Muscat constituted one of the most important parts of those port cities’ commerce.

However, Oman under the Yarriba’s did not remain peaceful and plunged into a civil war which invited Persian interference too. Albusaid’s significant triumph over the ruling Yarriba dynasty in the civil war during the 1720s changed the course of Omani history. During these years of anarchy in Oman, Ahmad bin Sai’d was recognized as Imam c. 1743–44 and Muscat began to develop again in importance. During this period other powers, namely the Ottoman and Persians, were relatively weak and there were no foreign rivals for the trade there until the Qwasim and the Utub, who captured Bahrain island in 1783 and emerged as maritime rivals (Bosworth 2007:418).

The growing trade links of Muscat with India at the beginning of the 19th century channelized a series of opportunities for the merchants of western India, especially from Sindh, Kachchh and Bombay, and in the East for the traders of Calcutta. Numerous varieties of Indian produce including cotton, timber, rice, sugar, spices and ghee were brought to Oman for both home consumption and re-exportation.

The rise of Muscat was corroborated with many simultaneous developments such as the consolidation of Omani power in the Arabian waters and the occupation of Gwadar on the Makran coast, Qishim and Hormuz and Bandar Abbas and its dependencies on lease. The Sultan took keen interest in mercantile activities and built up his fleet of 50 ships from 1790–1802/03. These ships crisscrossed the sea, encompassing several destinations and procuring their specialties.[2] The 18th-century profitable trading relations with Sindh and Kachchh had naturally raised the commercial importance of Muscat. From Sindh, the large boats employed in the trade to Muscat were from 30 to 50 tons in burthen and sailed unarmed principally from Karachi. A few of the largest belonged to the merchants at Vikkur and Darajah.[3] In return, the Muscat dhows loaded with these goods skirted the Gulf coastline of Basra, Bushire and Bahrain.

By 1800, Muscat from its situation as a trading emporium carried on direct and lucrative mercantile dealings with Kachchh, Baluchistan and Sindh (Malcolm 1800:278–79). Though the whole range of shipping was proficiently managed by the Arabs by plummeting actively as freighters, the rest of the trade activities of collection, stores, sales and purchase were turned by their Indian counterparts. It was also the Indians who efficiently managed the financial facets behind the scenes.

The favourable conditions in Muscat and the early success of the Sindhi and Kachchhi Bhatias resulted in an increased mercantile diaspora in Muscat. At the turn of the 18th century, the representation of mercantile activities was unambiguous in the Gulf region, demonstrating a large volume of merchandise that was either imported or exported through Muscat and Basra in the Persian Gulf. It was reckoned that more than half of the Indian imports at Bushire and Basra, and the bulk of those into Bahrain, were received through Muscat (Lorimer 1986:166). The transit trade covered all the articles of commerce in the Gulf.

Lewis Pelly, a British Political Resident, described the trading web of Arabia as woven with Europe in the west, territories to the East of India and from India itself. The second route connected Western India, Muscat, East Africa and the Aden coastline of Arabia. The caravan trade, in its third form, commenced from Mished Tbrah and other routes in southern central Asia; down through Zend to Bandar Abbas. Goods came in caravans by the way of Teheran, Isfahan and Shiraz down to Bushire. Goods also funnelled via Tigris through a river steamer or a boat to Basra while others were transhipped into seagoing craft for transit down the Gulf. The trade in miscellaneous goods flowed from the ports of the western coastline between Kuwait and ‘Frains’ to the north and Ras al Khayimah to the south (Pelly 1863:228).

With that, what is also evident is that Sindhi merchants, though small in number, were spread throughout the Persian Gulf and were found in places as diverse as Yazd, Bandar Abbas, Kerman, Lingah, besides the main Indian commercial centres namely Muscat, Basra and Bahrain. In the Persian Gulf, the British official records indicate that the considerable numbers of Sindhis managed to trade in less favourable regions by a foreigner. For instance, at Bandar Abbas, there were 60 Khojas, 30 to 40 Shikarpuri Banias and four or five Kachchhi Bhatias. They were principally the gumasta or agents of Sindh or Bombay firms.

They were prosperous, and complained only of the difficulties incurred in collecting their goods and money from the interiors. For instance, they had ordered and paid advances to the cotton growers in the province of Kerman. However, when the crop was ready, the Persian governor of Kerman refused to allow the goods to pass unless the merchants would consent to his taking half of them at the price which they advanced to the producers. This deprived the merchants of the profits accruing from the high prices. The governor placed himself in a position to give priority of export to the half he might seize. So the merchants would always face the risk of any fall in prices before their part of the cotton reached the markets of Bombay. Also, due to inadequate mercantile transactions in the interiors of Bandar Abbas, the Indians had limited their direct operations and business to that coast itself. They also maintained trade relations with Kerman and Yazd where they had correspondents or commission agents, but did not keep any sort of transactions with the Persian subjects residing in the capital of Persia (Pelly 1864b:247, Pelly 1864a: 144–45)

In 1856, at Lingah, a port on the Persian coast, the Banias and other British Indian traders complained of an attempt to fix an increased percentage of duties on their goods. The demand was resisted as the treaty between Persia and England of 1841 did not allow more than 5 per cent to be charged (1867:138).[4] Sadlier Forster noted that, ‘There were neither Hindus nor Christians residing at Katif’ (Forster 1866:30). These experiences answer the question why Kachchhis, unlike Sindhis, chiefly concentrated their settlements in Muscat. They also endorse the argument that the spirited Sindhis were present in regions where other entrepreneurs were reluctant to settle.

Eventually, these Sindhis in the ports of the Persian Gulf largely invested their capital in pearl fishery operations and subsequently played a role in marketing and distributing the pearls. Fiscal support of fisheries and commercialization were the exclusive monopoly of a few rich Indian merchants, chiefly Banias and Khojas from Sindh, and Kachchh merchants who specialized in the classification, estimation, and commercialization of pearls.[5] The Sindhi traders, mainly the Thattai Bhatias, dealt in dates and pearls in the Persian Gulf.

In due course, their commercial network expanded in the purchase and export of pearls. Manama and Dubai became the hubs of these financers. One of the Thattai Bhatias, Narain Asarpota, describes in his autobiography the importance of his community in the pearl trade and emphasizes the value of trust which won them favours of both Arab and European clients. He recalls that Arab and Persian pearl dealers would deposit their money in the safes of his predecessors entirely on trust. These custodians of finance would lend them money too.[6] This trust-based commercial relationship worked on verbal terms, assurance or deeds which under-used monetary documentation. As Asarpota recollects, ‘The pearl divers normally keep no accounts. They neither give nor take bonds or agreements, and if any dispute arises, the entries in the Bhatias’ books are taken as evidence of the correctness of each item of supply and transaction’ (Asarpota 41–43).

These dealers not only owned most of the boats but advanced provisions, clothing and other essentials to the pearl fishers (Miles 1919:416). The industry chiefly worked on a system of advance credit. The role of the Bania in the pearl trade commenced at the entry level with advances allocated, and afterwards in the manner of valuing and paying for the harvest made by the crews. The agents made advances of money to the divers during the non-diving season, and in spring the boats were supplied with dates, rice and other provisions. This meant that the great majority of the profit was in the hands of the agents of pearl merchants, whether Hindu or others, who resided in the town of the littoral (Durand 1878:30).

The pearl export was chiefly directed towards India through local and Indian merchants and those pearls that reached Europe travelled through multiple intermediaries and a variety of overland and marine circuits. At the close of the 18th century, pearls were distributed to multiple outlets. In 1790, Manesty and Jones, for instance, listed a variety of markets to which pearls were directed from Bahrain, including Surat, Sindh, Calcutta, Bushire and Mocha via Muscat. From Bushire and the Indian ports they were exported to ‘Kandahar, Multan, India, Tartary and China’ (Saldanha 1986:408). In 1800, pearls worth 2 lakh rupees were sent to Persia from the southern shores of the Gulf. However, as the Indian stronghold over the pearl market increased, in three decades time, three-quarters of the produce was shipped to India, with the rest to Persia, Arabia and Turkey (Carter 2005:152). In 1819, Evan Napean, British officer, observed that the perfect pearls were reserved for Surat, from whence they were distributed throughout India. He analysed that ‘…all the pearls that are fished, are generally sold in the Indies because the Indians are not so difficult as we, and buy differently the rough ones as well as the smooth, taking the whole at a fixed price’ (Neapen 1819:190).

In the second half of the 19th century, the great bulk of the best pearl was sent to the Bombay market where, during the ‘share mania’ (a term used in reference to the intense interest in cotton trading which led to the formation of ‘The Native Share and Stock Brokers’ Association’), they fetched fancy prices. Bahrain was visited in the pearl fishing season by Sindhi pearl dealers who freighted to Bombay by the British India Steam Navigation Company’s mail steamer. Kuwait’s pearls and shells too were shipped to Bombay through Bahrain. In linking Muscat, Bahrain and Kuwait's trade to Bombay, Kachchhi and Sindhi pearl dealers imported large quantities of dollars and rupees from India to these ports during the fishing season (Ray 1885:547). In the chain of pearl circulation, Bahrain was the preliminary market and Muscat acted as the intermediate market between the pearl-banks and Bombay. Though the pearl fishery was not carried out near Oman, Muscat being closely connected with the Persian Gulf emerged as a chief intermediary market and it enriched the Bahrain-based Sindhi merchants, who controlled the sale of pearls from Bahrain to Bombay.

Further, access to the flourishing pearling business of the Persian Gulf profitably shaped up the axis network between the Gulf, Muscat and Bombay. This is evident from the statistical figures which reveal the ever-flourishing nature of the pearl business in this ambit. More than half of the value registered under the imports to Bombay represented pearls from Muscat and Persia. The same articles to the value of 8,42,000 rupees reached by parcel post: so that the import of pearls was put down at something over 20 lakh rupees by the year 1884–85.

By the close of the decade of the 1880s, the imports of pearls from Muscat and Persia showed an increase of 1. 2/5 lakhs rupees and re-exports of pearls and other jewellery increased to a nearly corresponding extent (AR 1888–99:107). It was more so because Bombay was closely connected with the fashion world of Paris which attracted status and fashion-conscious clients. The business relations between Bombay and Paris are well-echoed in an administrative report which states that a great impetus was given to the demand for pearls by the anticipation of large realizations at the Paris Exhibition, and in addition to the imports of 91,97,000 rupees received during the year, a much larger quantity of fine pearl jewellery left India before the end of 1899. Of the extraordinary increase of 55,30,511 rupees, unset pearls alone accounted for a trifle less than 54,00,000 rupees (AR 1899–1900:101).

The Sindhi capitalists in the pearl trade undoubtedly made great fortunes and very profitably shaped their strong diaspora in the Gulf regions. For their commercial services, they received several concessions. Some of the Bhatia merchants were given permission to buy land in their own names. However, with time, trade reverses opened chapters of misfortune, loss and bankruptcy in the lives of these merchants. The collapse of the pearling enterprise and the influx of cultured pearls transformed the economy of the Persian Gulf. For the Sindhis, this time was even more trying in terms of losses additionally occasioned by the Great Depression, followed by Partition.

Narain Asarpota painfully narrates how his family’s pearl trade passed through these turbulent times. His father, Vallabh Asarpota, who had flourished in the pearl trade in Bahrain and Dubai, was severely affected by the financial crisis. His debtors defaulted in their payments and creditors levelled hammering pressure on him to return their money. In this critical situation, the jewels of his wife and family came in handy to avert the looming bankruptcy. Barring some of their assets, whatever was lost at this time was lost forever (Asarpota 16–20).

There were many such cases of misfortune and the prosperity of the Thattai pearl merchants soon withered away. A range of corrective measures were adopted to relocate and some joined other business houses. In a desperate move, some of the merchants personally visited Paris in search of alternative markets for their stocks of pearls. However, their American counterparts, who by then were well-entrenched in the fashion markets, soon punctured their dreams. Fortunately, the discovery of oil opened new doors of opportunities for the pearl traders and financiers from the Thattai Bhatia communities of Bahrain and Abu Dhabi. The economic players were thus compelled to either diversify or shut their commercial operations. On a positive note, oil, the new global commodity, offered a fresh opportunity to remake the fortunes and retain the prominence.

[1] Pareira, a Portuguese commander, asked Narauttam, the 'Banian', for the hand of his beautiful daughter in marriage. Narauttam declined the proposal because of religious difference. The incident led him to help the Yarriba ruler of Muscat to expel the Portuguese from Muscat in 1650. This support proved beneficial for Narauttam and the other Banias. Narauttam and his family, and subsequently all the Bania traders, were exempted from paying Jizia, an annual per capita tax (Badger 1871:81-82).

[2] Between 1798 and 1806, an economic high was noticed because of the Anglo-French war. It was reported that the Omanis, ‘in the course of ten years have increased their tonnage from a number of Dows and Dingeys, and two or three old ships, to upwards of fifty fine ships’ (Sheriff 1987:82, 83).

[3] Amongst the seaports of Sindh, Bunder Vikkur ranked next in importance to Karachi. The port takes its name from a small village in the vicinity; but the town is called Baree Gorah after the Gorah river (Carless 1837:466).

[4] The treaty of 1841 ceased to operate on the breaking out of the war between England and Persia in 1856 and none of the provisions were revived by the treaty of 1857.

[5] Here the term Bania is applicable to both the Khoja and Hindu merchants of Sindh and Kachchh.

[6] A rough estimate shows that during the late 1920s, there were about 50 Bhatia-owned pedis (companies) involved in pearl financing on the Trucial Coast (Forster 1866).

Abbreviations

MSA: Maharashtra State Archives, Mumbai

PSD: Political and Secret Department Diaries, 1800–19

AR: Administration Reports of the Bombay Presidency, 1860–99

Asarpota, Narain. My Life My Destination. Abu-Dhabi.

Badger, G.P. 1871. A History of the Imaums and Sayyids of Oman. London: Hakluyt Society.

Barendse R.J. 2009. Arabian Sea in 1700–1763; The Western Indian Ocean in the Eighteenth Century. Netherland: Brill.

Bosworth, Clifford Edmund. 2007. Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Carless, Lieutenant T.G. 1837. Memoir to accompany the Survey of the Delta of the Indus, in 1837. In Report on the Administration of the Persian Gulf, Selections from the Records of the Government of India, Publication 14284, MSA. Calcutta: Foreign Department Press.

Carter, Robert. 2005. The History and Prehistory of Pearling in the Persian Gulf. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV.

Durand, Captain E.L. 1878. First Assistant Political Resident, Persian Gulf. ‘Notes on the Pearl Fisheries of the Persian Gulf’

Fitzgerald, W.R.S.V. and others. 1867. ‘To Her Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India in Council, London’, # 37 of 1867, 8th June 1867, Bombay Castle, MSA, PD, Vol. # 87.

Sadlier, Forster. 1866. Diary of a Journey Across Arabia, During the Year 1819. Bombay: Education Society Press.

Saldanha, J.A. 1986. The Persian Gulf Precis, vol. 3. Buckinghamshire, England: Archives Edition.

Leech, Lieutenant. 1856 [1837]. Memoirs on the Trade &c. of the Port of Mandvi in Kutch, May, in Miscellaneous Information, Connected with the Province of Kutch, ed. S.N. Raikes, in Selections from Bombay Government Records, New Series XV: 3315, MSA, Bombay: Bomaby Education Society Press, pp. 222–23.

Lorimer, J.G. 1986. Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman and Central Arabia, vol. I (Historical) Part I-I. Oxford: G. B. Archives Edition.

Malcolm, John. 1800. Envoy, Bombay frigate, Muscat, to Archibald Bagle, assistant Surgeon, 8 January 1800, MSA, SPD Diary # 87 of 1800, pp. 278–79.

Markovits, Claude. 1999. ‘Indian Merchant Networks outside India in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: A Preliminary Survey,’ Modern Asian Studies, 33.4:

———. 2001. The Global World of Indian Merchants 1750-1947. London: Cambridge University Press.

Miles, S.B. 1919. The Countries of the Persian Gulf, vol. 1. London: Harrison & Sons.

Neapen, Evan. 1819. Minutes by the president in council, Evan Napean, to the Marquis Hastings, January 11, 1819, MSA, PSD, Diary #310.

Pelly, Lieut. Col Lewis. 1863. Memorandum by Lieut. Col Lewis Pelly, acting Political Resident, Persian Gulf, Bushire, January 12, 1863 MSA, PD, Vol. # 42 1863.

————. 1864a. Lieutenant Colonel Lewis Pelly, acting Political Resident, Persian Gulf, to W. H. Havelock, officiating Secretary to Government, Bombay, 16th January 1864, Bushire, pp. 144-145.

————. 1864b. ‘Remarks on the Port of Lingah the island of Kishim and the port of Bunder Abass and its neighbourhood’, in The Transactions of Bombay Geographic Society, Vol. # XVII, January 1863 – December 1864. Bombay: Education Society Press.

Ray, Rajat Kanta. 1995. ‘Asian Capital in the Age of European Domination: The Rise of the Bazaar, 1800–1914’, in Modern Asian Studies 29.3: 449–554.

Sampat, Dungarshi Dharamshi. 1935. Kutchnu Vepartantra. Karachi.

———. 1939. ‘Foreword’ in Muniraj Vidhyavijayji, Mari Sindh Yatra. Ujjain: Deepchand Banthia.

Sheriff , Abdul. 1987. Slaves, Spices & Ivory in Zanzibar. Oxford: James Currey.