[First appeared as Chapter 13 of Sufism and Bhakti Movement, Eternal Relevance, edited by Hamid Hussain and published by Manak Publications (P) Ltd in 2007. Reproduced with permission from Manak Publications (P) Ltd.]

The oral traditions around small and large shrines of saints based primarily on memory and legends fill the gap in written sources about the daily life of the people in Medieval Sindh in the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent. In pre-Islamic Sindh, a cluster of specific sects and cults observing various symbols with their own beliefs, existed within Hinduism and Buddhism. Its prominent navigable river Indus or Sindh Darya was incontestably sanctified by the indigenous population over a long period of time. Its regular flooding and receding which brought promise of vegetation on the cultivable soil was attributed to a divine spirit. By extension the divinity was also identified with the act of human fertilization. Coinciding with the advent of Ismailism in Sindh in 10th century A.D., the supernatural divinity was given a distinct human shape in a Muslim Sufi patron, Darya Shah Zinda Pir popularly known as Khwaja Khizr. The legend of Zinda Pir, which resembles strongly with the Kazaruni Sufis of Iran, originated as a water spirit to guide mariners and travellers on the Indus river and the Arabian sea. The folkloric tradition of the region elevated Zinda Pir to something like a river god and his followers both Muslims and Hindus became Daryapanthis. This is despite the fact that Muslims were not religiously supposed to worship water or river. Interestingly in the tomb of Mangho Pir, follower of Khwaja Khizr, located near Karachi crocodiles were shown in painting as a reminder to protect the boatsmen on the river from possible risks.

In a parallel development arising probably from Islamisation or Hindu reaction to Muslim orthodoxy and political domination, Iegends of another river god of the Hindus in Oderlal or Jhulelal appeared around this period. The appropriation of river gods was lost in time but it created many legends attached to the river which evolved as integral part of collective memory of the Sindhi community. This is expressed in literary writings and musical songs attributed to the Pirs and Jhulelal. The purpose of this paper is to trace the legends of Khwaja Khizr and Jhulelal prompting the medieval river culture and to find out explanation to identify the process of acculturation in human beliefs.

The Sindhu or Indus river, one of the longest in the world with an astonishing length of 2900 kms finds its vivid description in the Rig Veda and for its living force and divinity the ancient river has often been referred to in masculine gender (the other being Brahmputra) with its sound compared to the roar of thunderstorms inspiring a sense of awe in the minds of the local inhabitants. In the Indian epic Ramayana it is given the title of Mahanadi while in the Mahabharata it is mentioned with reverence along with two other holy rivers: the Ganga and now hidden Saraswati. Interestingly it also finds mention not only in the literary works of Kalidas, Bana, Panini but in Greco-Roman literary works also. Before the Muslim Arab conquest of Sindh in the early eighth century one of the main factors that influenced Arab relations with its people was the topographical peculiarities of the region viz. existence of the Arabian Sea. Trade was the determining factor in these relations. Various historical documents confirm that the Arab civilization flourished largely on Indian trade.[i]

However, the major problem concerning knowledge of maritime activities in the Arabian Sea at the beginning of the eighth century arises from a paucity of source material on medieval trade. Coupled with this is our inability to distinguish between medieval trade from what preceded it. G.F. Hourani, an expert on medieval Arab trade makes the point that the Arabs’ predominant interest in the Arabian Sea was commerce rather than passion for the spread of Islam.[ii] A recent compilation on the Indian Ocean helps us locate some important ports and their utility, especially those of Deybul, Bandar Lahori and Thatta, all connected with Indus river for Arab and later Turkish conquerors.[iii] It is noteworthy that in the seventh century A.D. the Medes of Sindh were backed by the merchants of Deybul. It is mentioned that Sindh ruler Chach's son Dahir was encouraging piracy which involved some Muslim women being sent by the king of Sila to Hajjaj to allow them to rejoin their families.[iv] It is alleged that one of the reasons for Muhammad bin Qasim's invasion of Sindh was to penalise the sea pirates.[v] The city and port of Deybul find repeated references not only at the time of the Arab conquest but even later around the 10th century when it is designated as the big port at the mouth of the Indus. The location of Deybul on the Indus and at the edge of the Ocean is derived from certain repetitions of topographical elements endorsed in the passages of literature. Ibn Hawkal mentions thrice the position of Deybul in his writings. One also reads in Hudud-al Alam (982 AD) that ‘Deybul is a city to the south on the coast of the Big Sea. It is the habitat of merchants...’[vi]

Muqaddisi in the same period gives a specific detail on the location of the city and says that the Mihran (Indus) falls beyond it where the sea reaches its wall.[vii] Al-Biruni, at the beginning of the 11th century twice mentions the Indus river which falls into the ocean.[viii]

However, despite such a commercial location our sources do not mention either Khwaja Khizr or his cult at least prior to the ninth century A.D. The Chachnama dealing with the Arab conquest of Sindh too fails to point out the river cult while al-Baladhuri who was a close contemporary of the author of Chachnama and who brings down the history of Sindh up to 842 A.D. in his Arabic work, Futuh al-Buldan does not mention the Khwaja or Zinda Pir or divinity of water cult. Clearly the legends relating to Khwaja Khizr emerged some time in the 10th century, coinciding with the introduction of Ismailism in that part of Sindh where the Indus river merged into the Arabian Sea. The first Ismaili missionary who came to Sindh in 883 AD began rather secret propaganda in favour of the Ismaili Imam.[ix] Later Ismaili doctrines were encouraged and adopted under the Sumra ruling class whose ancestory is controversial.[x] The author of Chachnama mentions Jats and Sammas as the original tribes of Sindh without any reference to Sumras. It is evident that political developments in the weakening hold of Arabs both of Sindh origin and in the Islamic world might have partially encouraged the Ismaili doctrines of the Fatimids of Egypt through their increasing trade activities.

While the interrelationship of communities witnessed gradual assimilation in Sindh, the Fatimids, a breakaway group within Islam were also trying in favour of Ismaili doctrines through the Yemenite dawa.[xi] The Ismailis succeeded in building up their influence in lower Sindh and finally in the 11th century with the support of the Sumra community. Ismailism was manifest in Sindhi society subscribing to the Ismaili cause of the Fatimids, and Sindh with Deybul port was important for the Fatimids in terms of their plan for expanding influence, due to its geographical location in relation to the Ismaili dawa centre in Yemen.[xii] Sindh also offered commercial advantage and possession of Deybul and other ports to the Fatimids which could deprive their rival Abbasids of lucrative trade on the Indian coast. The two-fold aim of the Fatimids were to gain supremacy over the Abbasids by controlling trade on the Arabian Sea through Sindh ports and to perpetuate their impact through the Ismaili dawa. The Ismaili missionaries preceded the political and commercial power and the supporting evidence comes from Idris history of Sindh dawa.[xiii] According to one geographer al-Maqdisi, who visited Sindh in AH 325/ 990 AD, the Khutba was read in Multan in the name of the Fatimids and all decisions taken accordingly.

The river cult which had its origin among the indigenous population for its sanctity was possibly exploited by the Ismailis to create a sort of divinity with Khwaja Khizr or Zinda Pir. It appears that the role of mercantile traditions of Sindh have long been a significant factor. Khwaja Khizr not only became patron saint of bhishtis of Indus river and protector of boatsmen but was regarded as ‘god of water’ both by the Hindus and Muslims. What the Kazaruni Sufis were doing for mariners and travellers on the sea-route between the Persian Gulf, India and China a little later,[xiv] Khwaja Khizr had done the same for Sindh Darya, the water of which was no less sanctified than the wells of Zam Zam in Mecca. For Kazaruni Sufis protection of mariners from storms and pirates through magic became the focal point of their zawia.[xv] Similarly Khwaja Khizr possessed all these properties, with its baraka and Khanqah built on the river bank at Bakhar-Sukkar.

The cult of Khwaja Khizr followed by the Daryapanthis was at its peak under the Sumra rule in lower Sindh.[xvi] It was very popular with traders undertaking travel on water. Since trade was a risky business, mutual trust and confidence among business partners of trade should exist and one of the ways to establish confidence was to share the same cult within ethnic groups or followers with missionary zeal. One of the factors to which the decline of the Sumras is attributed was the change in the water course of Indus which began to flow a more westerly course and the diminishing of water in the main channel of the river adversely affecting trading prosperity of Darya followers. However despite this Zinda Pir shrines at Sukkur and Bakhar continued attracting his followers. Within Sufism there has always been strong emphasis upon the spiritual interpretation of the pilgrimage (ziyarat). A visit to a shrine or dargah (mazar) is a good substitute for pilgrimage to Mecca.[xvii] Without belittling the importance of Haj and respect shown to the Hajis, pilgrimage to Zinda Pir's shrine played an important role for the Daryapanthis. As a matter of fact sailors and boatsmen never ceased reporting that the Khwaja was always present and living and appeared from time to time to his devotees in order to help them and work miracles.

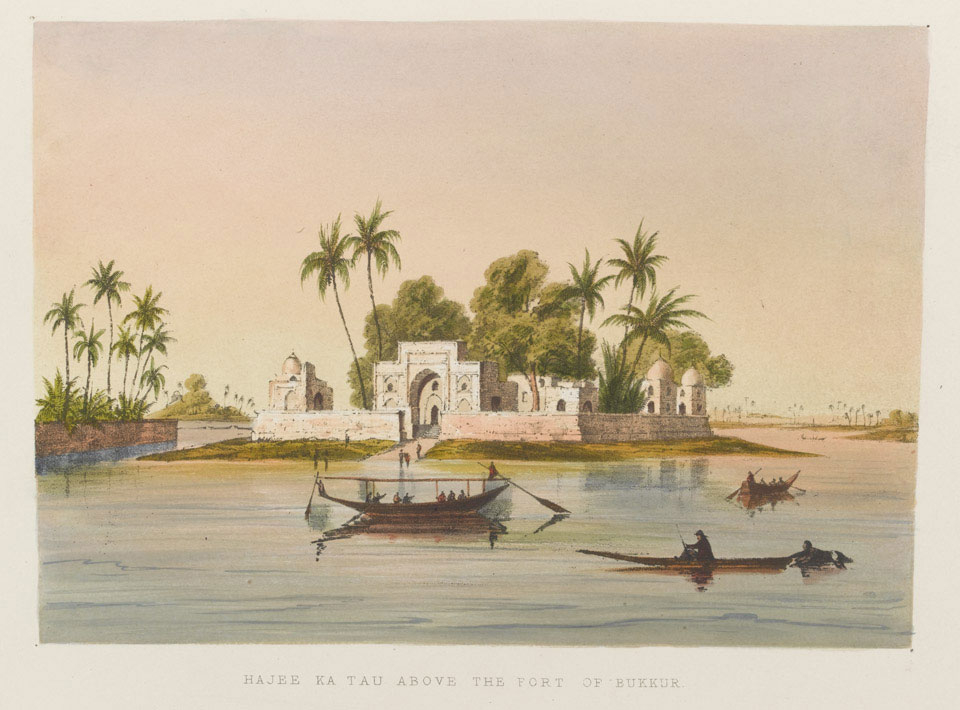

Hajee Ka Tau above the Fort of Bukkur

Although the documented history of Sufism starts from the Delhi Sultanate yet the existence of Muslim saints and a theory of saintliness is attested from the beginning of settlement of Muslims. These holy individuals not as yet attached to Sufi orders were worshipped in the region of Sindh under Arab domination from 8th to 11th centuries and then in Punjab under the Ghaznavids. Hujwiri (d. 1072)'s treatise on Sufism known in Persian as Kashful-mahzub said, ‘Through the blessings of the saint rain falls from heaven and through the purity of their lives, the plants sprang up from the earth and through their spiritual influence the Muslims gain victories over the unbelievers.’[xviii]

The divinity of Khwaja Khizr or Zinda Pir appears to have achieved two-fold aim of meeting the spiritual needs of the sailors and traders engaged in the Indus river and sea trade and also confirming the sanctity of the river by the indigenous population. The time period of emergence of this saint regarded as ‘immortal Pir of water’, especially when Muslims are not supposed to worship water creates suspicion about his identity. Secondly the Kazaruni order of Sufis of Iran who stood for protection of mariners on the sea was a later development. For historians the integrity of Khwaja Khizr is debatable and it is only by 19th century that the Muslims had somehow agreed that Khizr, a patron saint associated with water had discovered ab-i-hayat (the elixir of life), of which he was the guardian, as he was also of the seas.[xix] The long silence between 11th century to 18th century by the historians was broken when the colonial travellers visited Sindh, explored its legends and the Khanqah at Sukkur that the Khwaja Khizr regained his prominent place with the historians. Lt. Burnes in his travels of Bokhara refers to the belief of fishermen in the Khwaja although calling fisherfolk of Sindh as superstitious.[xx] Abbott in his Sindh: A Reinterpretation has given the legend of Khwaja Khizr, the river deity whose shrine stands in the Indus on the other side of Rohri.[xxi] Lt. Burton supports the view that Sindhis had utmost faith in river-god.[xxii] Hamilton in his New Account of the East Indies noted that for crossing the river people used earthern vessels, jars and mussucks (leather hide balloons) with submission to river-god?[xxiii] A modern scholar, H.T. Sorley, while symbolising Shah Abdul Latif as ‘an epitome of Hindu-Muslim culture’, refers to his work Sur Samundri which immortalises the trading traditions of Sindh and anguish of women at separation from husband sailors. What is important is that the shrine of Khwaja Khizr at Sukkur, known under the name of Zinda Pir, venerated for ages both by Muslims and Hindus has had the keepers of the shrine from both the communities. There is a strong case of Ismaili affiliation with Khwaja Khizr and river cult in many of its rituals especially, when we find that the shrine of Khwaja was built at the Indus bank at Sukkur which was a part of Ismaili stronghold then. In fact, Khwaja Zinda Pir's cult was at its peak under the Sumras who were Ismailis. Again the moon becomes the important symbol in water worship rituals. The day of full moon and new moon were sacred to Zinda Pir. Similarly Ismaili influence finds expression in festival of Chaliha (40 days) and sanctity of Fridays. The numerical numbers five and seven were always celebrated and four corner lamps were installed for light in river rituals to which was added a fifth lamp on behalf of worshipper. Deeply impressed by Ismaili beliefs, seven objects stood like seven Imams of the Shia Ismailis and 5 lamps, being the symbol of palm of hand. Like Egypt, Sindh had depended for its fertility on floods, and the ceremonies were originally intended as charms to promote the growth of corn by the process of imitative magic. These numerals strongly suggest that the river Pir was associated with Ismaili beliefs. The strongest point of medieval Sindh is that its population believed more in Pirs and Sufis and the Sufi was called la-kufi (without a specific creed).

The Ismailis had adopted a policy of constructing links between the convert and his earlier religious beliefs. Usually the process of conversion consisted of ‘a journey which included remnants of earlier religion of the converts, assimilating the local religious beliefs’.[xxiv] In the inscription on the island of Zinda Pir the river is addressed as Khizr. It reads, ‘when the sublime dargah appeared, which is surrounded by the waters of the Khizr, Khizr wrote this in pleading verse, its date is found from the Court of God.’[xxv] The inscription reminds one nevertheless of the Ismaili theory of Satr (dissimulation of work, Futuh al-Buldan the Imam, and of the ultimate reality) and of the idea ‘that the hidden Imam will reappear at the end of time’—a belief shared by a number of dissident branches of the Ismailis: both Shia Twelvers and Ismaili Seveners. Such parallels can be drawn from the Panch Priya Cult or even Baba Ramdeo Pir tradition.[xxvi]

The apparent symbols of affiliation of Zinda Pir to Ismailism made the Khwaja Khizr a highly controversial figure of general renown in the Sunni Muslim world. Since India was dominated by Sunnism both under the Sultanate and the Mughals, the controversy about this cult was bound to remain as the Sunnis were opposed to Ismailis. Gradually the Khwaja was identified with the Prophet Ilyas and is believed to reside in the seas and waters and command over a fish and crocodiles. He is supposed to have drunk water of Zamzam of Mecca wells and therefore the people propitiated him at child birth at marriages, during flooding of Indus and also by launching paper boats with flags.

As the river-god concept coincided with Ismaili thought, it is possible that Uderolal or Jhulelal could have tried to use Ismaili rituals as to counter the appeal of Zinda Pir. Uderolal or Jhulelal was also known as Shaikh Tahir whose shrine was visited both by Hindus and Muslims. The cult of Jhulelal which gained popularity a little later was also based on worship of water, light and reverence for the river Indus.[xxvii] The flooding of the river Indus was an occasion for celebration which continued for 40 days. Fairs were held at the sacred sites on the bank of the river viz. Johejo (Nasrpur),[xxviii] Thatta and at shrines of Zinda Pir at Sukkur and of Mangho Pir at Karachi.[xxix] Later the tomb of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar at Sehwan was also added and venerated by the boatsmen where the Indus was a subject to Sufi's command. ‘No vessel dares to pass without making a propritiary offering at his tomb’: thus runs the popular legend. Thousands of pilgrims flocked to the consecrated spot and the Hindus joined the Muslims in declaring Lal as a Hindu name while Muslims associated it with their faith. Both Lt. Burton and Col. Todd have certified this while on their visit to Sindh in the 19th century.[xxx] Haig also confirms this in his work on the Indus Delta.[xxxi] Even today Jhulelal is attributed the epithet of Bera-i-par i.e. safe crossing of the river by boatsmen.

Uderolal is revered as the River god who saved the Sindhis from the tyranny and fanatical attitude of a Muhammadan ruler of Sindh.[xxxii] Legend has it that a handsome young man emerged from the river on a horse, showed many miracles and saved the people from cultural genocide. His miracles included getting into the Indus at Nasrpur and emerging out of it at Sukkur while the reverse of which was performed by Darya Pir Khwaja Khizr who entered the river at Sukkur and emerged out at Nasrpur. The creation of parallel gods receiving respect from the common folk both Muslims and Hindus remained supplementary in the observance of the rituals conducted by their followers who were called Daryapanthis. For them the Chahilio or 40 days was a period of activity and this period coincided with the flooding of the Indus. The coming of the flood was celebrated by the people by taking a Bahrana (offering-temple) to the sea-god in procession when the Indus water approached the village canal or lake through its various branches. Five lamps were lighted, seven objects were spread, music and dance was performed to welcome the river god. Barren women performed the ritual of taking bath in the flooded water to gain human fertility. The day of full moon and the new moon and Fridays were sacred to the river celebrations.[xxxiii]

Among the Daryapanthis were the Lohanas, Thakurs and a section of Aroras (from Alor).[xxxiv] We notice earlier references to Lohanas in Chachnama who were a powerful tribe but under an apparent confusion of terms were said to have included the original tribes of Samma and Lakha. The Lohanas were mostly merchants and traders while some of them were officials also.[xxxv] It is also believed that some Lohanas and Thakurs were converted to Ismailism by Pir Sadruddin in a peaceful manner.[xxxvi] Despite their being Daryapanthis they worshipped the Hindu deities and quite some time later in the 16th century some of them adopted the path of Guru Nanak and were called Nanakpanthis.[xxxvii] Most of the Daryapanthis were settled in the towns of Shikarpur, Sukkur, Rohri and Ghotki which had the Indus as source of water. It seems that there were no serious religious differences among the Sindhi castes. In fact there was very little religion among Sindhis that could be taken as strict Hinduism and therefore they were more prone to assimilation, possible Islamization and positive results of the Sufi zeal. According to D.N. McLean the Buddhists who were a major component of population at the time of Arab conquest of Sindh later collaborated more readily with the Muslim Arabs than the Hindus which possibly resulted in a process of absorption contributing to comparatively rapid extinction of Buddhists in Sindh. However it could not always be a one-way process from a non-Islamic way of life to an Islamic one. S.C. Misra focusses on the impact of socio-cultural changes during medieval times leading to two simultaneous processes: indigenization and Islamization. In fact indigenization gave rise to assimilation, not always consciously. The case of Lohanas, Sudhas and Daryapanthis are examples in point. Sindh was exposed to external influences both from the sea and overland connections making it on the one hand a meeting point of different cultures and on the other a bridge between western and Central Asia and India. The local elements assimilated these influences over a period of time and the image of parallel gods of water whether Khwaja Khizr Zinda Pir of the Muslims or Jhulelal of the Hindus are pointers in this direction. A subconscious reaction to Muslim domination in actual life of Sindh seems to have bred a hostile attitude which created a liking for such personalities and cults who were credited with cordiality of inter-relationship of different communities and Daryapanthis were one among them. Even during the Mughal period, despite succession disputes among the Daryapanthis, the water belief continued to flourish with all their divisions intact. Recently such a phenomenon for communal harmony has been officially revived in the regular annual Sindhu Darshan festival at Leh in higher Himalayas, where the Indus river originates on the Indian side.

Note

'Khwaja Khizr and River Cult in Medieval Sindh' by M.L. Bhatia was sourced for this Sahapedia module by Saloni Kapur. It first appeared as Chapter 13 of Sufism and Bhakti Movement, Eternal Relevance edited by Hamid Hussain, published by Manak Publications (P) Ltd. New Delhi 2007.

[i] Al-Baladhuri, Futuh al-Buldan, ed. M.J. E Goeje, Leiden 1906; F.C. Murgotten (tr. From Arabic), Origins of the Islamic State II, New York 1924. Also see H.A.R. Gibb, The Arabic Conquest in Central Asia, London, 1923, and H.M. Elliot and John Dowson, The History of India as told by its Own Historians I, London 1867, repr. Kitab Mahal, Allahabad n.d., pp. 113-30. The reprint edition has been used throughout.

[ii] G.F. Hourani, Arab Seafaring in the Indian Ocean in the Ancient and Early Medieval Times, Beirut, 1963, p. 39.

[iii] Himanshu Prabha Ray, ed., Archaeology of Seafaring: The Indian Ocean in the Ancient Period, New Delhi, 1999, pp. 70–153.

[iv] Muhammad Yusuf Abbasi, ‘Muhammad ibn Qasim's Conquest of Sindh: A Military Appraisal’, Journal of Central Asia 2 (1979), pp. 159–88.

[v] Chachnama, popularly known as Tarikh-i-Hind 0-Sindh (ed) Umar bin Muhd. Daudpota, Delhi, 1939, p. 11. For English translation from the Persian, see Mirza Kalichbeg Fredunbeg, Chachnama, An Ancient History of Sindh, Delhi, 1900, 1929; Al-Baladhuri, Futuh al-Buldan, op. cit., pp. 435–36 Cf. I.H. Qureshi believes that it is wrong to attribute Muhd-bin Qasim's invasion to penalise the offenders. The Muslim Community of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent, The Hague, 1962, p. 35.

[vi] V. Minorsky (tr. With annotations), Hudud al-‘alam, Gibb Memorial Series, London 1937, p. 372; Monique Kervran, in her article on 'Multiple Ports at the mouth of the river Indus', in H.P. Ray (ed.), Archaeology of Seafaring, op. cit., p. 87, argues that Karachi itself represents Debal (Deybul) while Lt. R.F. Burton, a British civil servant who wrote about the legends, stories, climate and geography of Sindh in the mid-19th century, quoted in his works, Unhappy Valley I, p. 128, and Scinde, p. 380, that 'Thatta of the Delhi Sultanate period occupies the ground of ancient Dewal (Deybul) on account of a product, Shal-i-Debali, which is still known as shal (shawl) of Thatta manufacture'. Elliot and Dowson, op. cit., I, at p. 307 on the authority of Tuhfat-al Kiram of Ali Sher Khan, assert that 'what is now Bandar Lahori was in former times called Bandar Debal'. Also see S.Q. Fatimi, 'The Twin Ports of Daybul: a study in the Early Maritime History of Sindh', in Hamida Khuhro (ed.), Sindh through the Centuries, OUP, Karachi 1981, p. 100, n. 10; N.A. Baloch, 'The Most Probable Location of Daibul, the first Arab Settlement in Sindh', Dawn, Karachi, Feb. 4 (1951).

[vii] Al-Muqaddisi, Ahsan al-Taqasim fi Ma'rifat al-aqalim, ed. M.J.De Goeje, Leiden 1966, pp. 479–82.

[viii] Edward C. Sachau (tr.), Alberuni's India, London 1910, repr. Delhi 1964, I, p. 208, II, p. 320.

[ix] Farhad Daftary, 'A Major Schism in the Early Ismaili Movement', in Studia Islamica 77 (1993), pp. 123–29 (see Index Islamicus 1993 preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford); M. Brett, 'The mim, the 'ayn and the making of Isma'ilism', in BSOAS 57, I, 1994, pp. 25-9. Also see Farhad Daftary, The Isma'ilis, Their History and Doctrines, Cambridge 1990; Ismail K. Poonawala, Bibliography of Ismaili Literature, in Studies in Near Eastern Culture and Society, Univ. California, Los Angeles 1977; W. Ivanow, A Guide to Ismaili Literature, London 1933, Mercantile groups easily came under. the influence of Ismailism, whether they were Sindhis or Gujarati Bohras.

[x] The Sumras appear to claim descent from the Arabs of Samarra who arrived in Sindh, served as ‘Abbasid governors and had been sent with a number of other tribes to counteract propaganda against the ‘Abbasids. The opposition was contained but, taking the opportunity of declining caliphate power, a number of Arab tribes and native chiefs seized power in different parts of Sindh in the latter half of the ninth century and carved out independent principalities of their own. The migrant Sumras got possession of parts of Sindh on the left bank of the Indus, from which they expelled the original inhabitants, the Sammas, who took refuge in Kutch. The Sumras took over Mansura in 1010, and then Multan. A section of the Sumra tribe had affiliated itself to the Ismailis in the 11th century. It is possible that many new converts were made at this time. Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, in an outward bid to curb Ismailism, was satisfied with tribute from the Ismaili rulers of Multan. The Sunni campaign against the Ismailis forced them to seek shelter in Mansura. The Sammas subsequently struck back from Kutch and became so powerful that they founded a dynasty in lower Sindh, ruling from 1338 to 1524, with independent status due to Sufist intervention and the inaccessibility of the region. Ibn Battuta could not distinguish between the Sumras and Sammas and wrote that their ancestors came with the army of Muhammad ibn Tughluq. H.T. Lambrick, in his Sindh: a General Introduction, Hyderabad 1964, p. 188, states that the Sammas were successors to the Sumras who had established their capital on the western delta, probably due to its capability for defence.

[xi] S.M. Stern, 'Ismaili Propaganda and Fatimid Rule in Sindh', Islamic Culture 22 (1949), pp. 298–307.

[xii] Bernard Lewis, The Fatimids and Routes to India, Istanbul, pp. 50-54; Abbas Hamdani 'The Fatimid-Abbasid Conflict in India', Islamic Culture, Hyderabad Dn., 41 (1967), pp. 185–91.

[xiii] Cited in S.M. Stern, Studies in Early Ismailism, Leiden, 1983, pp. 179–83, 251.

[xiv] Oddie (1991), p. 28 cited in Encyclopaedia of Islam, E.J. Brill. q.v. Kazaruni, Vol. IV, 851-52; A.J. Arberry, The Biography of Shaikh Abu Ishaq al-Kazaruni, III, 1950, pp. 163–72.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Aziz Ahmad, 'An Intellectual History of Islam in India', Islamic Surveys, Vol. VII, Edinburgh, 1969, p. 21

[xvii] Al-Hujwiri, The Kashf-ul Mahjub (ed) R.A. Nicholson, London, 1959, p. 329. The same views have been expressed by Bulleh Shah in his Punjabi verses. The shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar was often visited by the Daryapanthis.

[xviii] Ibid., pp. 212–13.

[xix] Encyclopaedia of Islam, new edition, Leiden, q.v. Khwaja Khizr; Islam in India: Studies and Commentaries (ed.) Christian W. Troll, New Delhi, 1985, pp. 15–16.

[xx] Alexander Burnes, Travels into Bokhara together with a Narrative of A Voyage to the Indus, Reprint Karachi, 1973, II, pp. 271–72.

[xxi] Cited in Elliot & Dawson, op. cit., I, p. 260.

[xxii] R.F. Burton, Unhappy Valley I, p. 128; idem, Scinde I, p. 122; Idem. Sindh Revisited I, London 1877, Reprint Delhi 1997, pp. 294–95.

[xxiii] Hamilton identifies the strong association of Pir Badr of Chittagong (Bengal) with Khwaja Khizr. Cited in Gait, Census Report 1901, p. 178.

[xxiv] J.N. Holister, The Shia of India, London, 1953, pp. 362, 383, 407; Muslim Sects and Divisions from the Selection on Muslim Sects in Kitab-ul-Milal (tr.) A.K. Kazi and J.G. Flynn, London, 1984, p. 164.

[xxv] Plates LXXV and LXXVI on Island of Zinda Pir in Henry Cousens, The Antiquities of Sindh, Reprint, Varanasi, 1975, p. 42.

[xxvi] These cults are of Ismaili origin. The Ramdeo tradition display Nizari Ismaili tendencies. The terminology used for both the river gods of Indus was almost same viz. Ziyarat to Shrine, Karamat (miracle), light, offering of flowers, dargah, Pir, Mazar. Both are Zinda Pir in the form of light and water.

[xxvii] E.H. Aitken, Gazetteer of the Province of Sindh, Vol. I, 1967, p. 163.

[xxviii] It is stated that the Hindu women at Junejo danced in the name of Uderolal at anyone's request even in the presence of menfolk, Tuhfat-i-Kiram, III, 153.

[xxix] Elliot and Dawson, op. cit., I, p. 260.

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] M.R. Haig, Indus Valley Delta Country, London, 1804, p. 71.

[xxxii] It is believed that Mirakh Shah, the fanatical ruler of Thatta ordered the Hindus to embrace Islam. However Sindhi legends attribute the appearance of Jhulelal to the injustices done by one Dalurai. The author of Tarikh-i-Tahiri states that infamous Dalurai persecuted the Hindus at Sehwan. When the people prayed for relief, Zinda Pir changed the course of Indus river on Friday and depopulated the town of Dalurai. The events pertaining to Dalurai are said to have taken place under the rule of Sumras (Fredenbeg, History of Sindh, II, pp. 28, 37).

[xxxiii] U.T. Thakur, Sindhi Culture, Bombay, 1959, p. 166.

[xxxiv] Ibid.

[xxxv] Chachnama (ed.) Umar bin Muhammad Daudpota, Delhi, 1939, pp. 39, 41, 49, etc.; Tuhfat-al Kiram, p. 143; Burton, Sindh, op. cit., pp. 314–17.

[xxxvi] R.V. Russell and Hiralal, Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, 4 Vols, Vol. III, Delhi, Reprint, 1975.

[xxxvii] Nanakpanthis were the followers of Guru Nanak who reacted favourably to his message in Sindh. Persian writers of the 16th and 17th centuries referred to the followers of Guru Nanak as Nanakpanthis or Nanakshahis. Zulfigar Ardistani, a Zoroastrian and the first non-Sikh chronicler, has left an account of Guru Nanak and the Nanakpanthis during the middle of the 17th century in his work, Dabistan-i-Mazahib, describing the five religions, viz. Magis, Hindus, Jews, Nazareans and Muslims. Another work, Risala-i-Nanak Shah-i-Darvesh, written in Persian in 1780 by one Budh Sing Arora at the request of Major James Browne and preserved in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, also mentions Sikh followers as Nanakpanthis. However, during the19th century, the word lost its popularity and was broadly replaced by the word Sikh. The followers of Srichand and the Udasi cult are sometimes linked as Nanakpanthis. See Ganda Singh, Contemporary Sources of Sikh History (1469–1708), Calcutta 1962.