Introduction

Monica Mahtani Bhojwani was born in a prisoner of war camp in France in 1940, an exciting story documented in her first book (see this link). Monica grew up in post-Partition Karachi. As a young bride, she moved to Gibraltar, where she and her husband Santu lived for ten years. After the subsequent twenty-five years in Las Palmas, they settled in USA to be near their children. Today Monica, who was never a typical Bhaiband woman, sees herself as an American Bhaiband. When she was young, she rebelled a little against forced traditions and found her own way of processing what she believed in and what she didn’t. Today, she understands her children's liberated and broadminded views and tries to move with the times.

In this historically authentic account of some important events of her life, we get a sense of what it was like for the Bhaiband women of Sindh.

Monica’s story

I was born in captivity, in 1940, in a French town called Royan which was under German occupation during the Second World War. My parents, Rukmani and Hotu Mahtani, set out from Gibraltar where our family had businesses, expecting to arrive in Karachi in fifteen days. Just a few hours short of Colombo, however, their ship, SS Kemmendine, was torpedoed by a German Raider, Atlantis and sank. The passengers who survived were taken as prisoners of war. The story of the weeks they spent on board the Atlantis and then the Norwegian cargo ship SS Tiranna, eventually being miraculously rescued when Tiranna sank and they were taken into a prison camp in Bordeaux, and of their lives in captivity, is written in this book.

The Sindhworki way of life

My grandfather, Khemchand Naumal Mahtani, was one of the early Sindhi traders, the Sindhworkis, who established their businesses in North Africa, Western Europe, and South America. They left Sindh to trade and set up their shops and started business wherever they found it lucrative. My grandfather made his fortune and came back to live in the family hometown Hyderabad, handing over the business to his sons. Now a wealthy man, he lived a comfortable life and devoted himself to the Theosophy movement, as did many of the intellectuals of Sindh in those days. But my grandmother, perhaps still bearing the scars of their days of struggle and poverty, continued to scrimp and save and resented his magnanimity and philanthropy. Whatever he earned, he would generously give away to his sisters and to anyone who needed help. My grandmother, on the other hand, was very materialistic.

This plaque commemorating Khemchand Mahtani and other contemporary supporters of the Theosophy movement was installed in the portico of Hyderabad’s Besant Hall when it was renovated in 1997. Photographed by Saaz Aggarwal, February 2013

My grandfather was the first in our family to go to Gibraltar. In those days, the men of our community left in shiploads and most of them were employed by Sindhis to work in their overseas shops. They went on a Sindhwork contract for three years and were not allowed to take their wives. After three years they came back to Hyderabad and spent time at home—sometimes six months, sometimes a year, depending on their contract with the firm they were working for. It was generally considered that the women could not go along with their husbands because it was a tough life for a Sindhi women and children out there. It was cold and basically a life for English servicemen and their families who were used to living on their own. Our women, having always lived a protected, cocooned life, would not be able to survive there. Besides, the daughter-in-laws back home needed to be with their in-laws to take care of the elders. I suppose my grandmother lived with her mother-in-law in a joint family with her sisters-in-law and their children. Every few years my grandfather would come home and spend a few months. Four sons were born to them: Mangharam, Partaprai, Hotu and Daulatram.

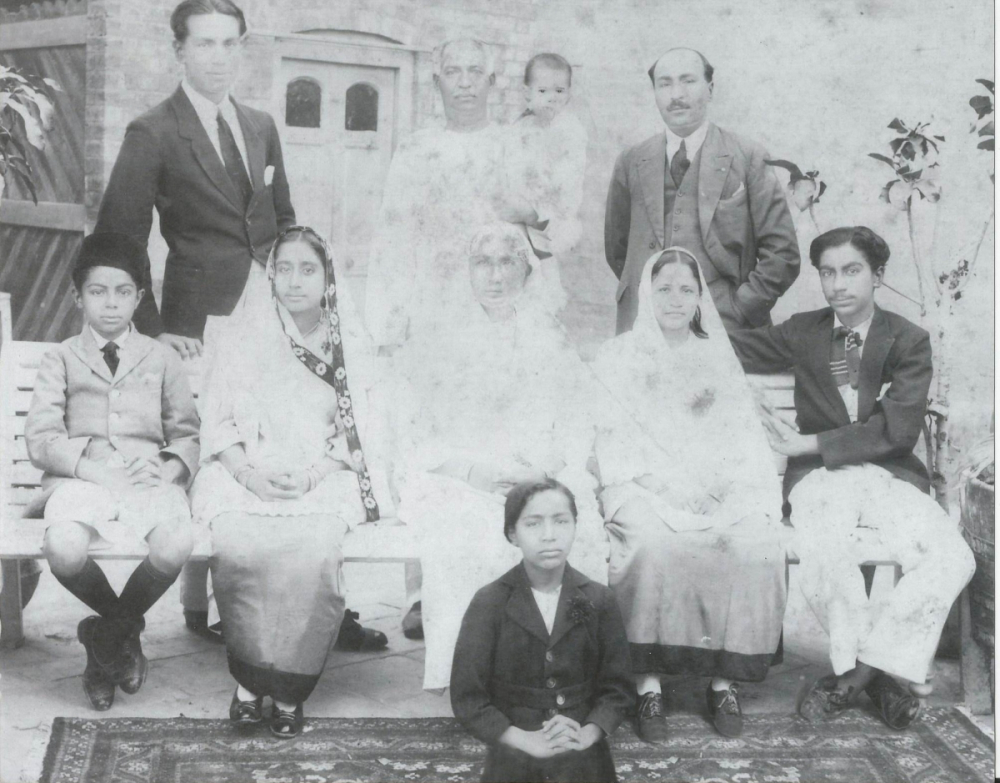

Standing: Partaprai, my grandfather Khemchand Naumal carrying Partaprai’s son Ram, Mangharam. Seated: Daulat, Parpati (Partaprai’s wife), Amma, Manghi (Mangharam’s wife), Hotu, my father. Sitting alone right in front in black is Mangharam’s daughter, Devi, the one who married an Amil and lived in Bombay. Date: c. 1926

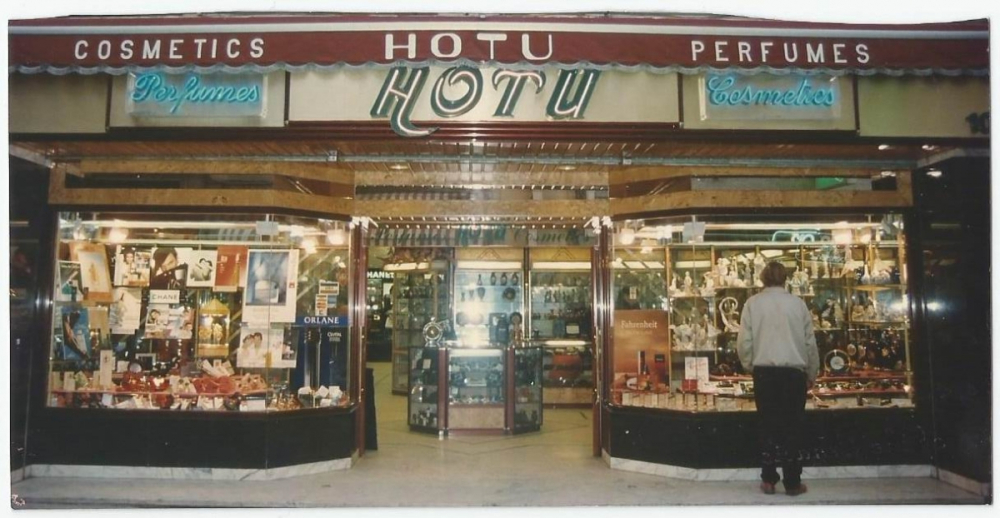

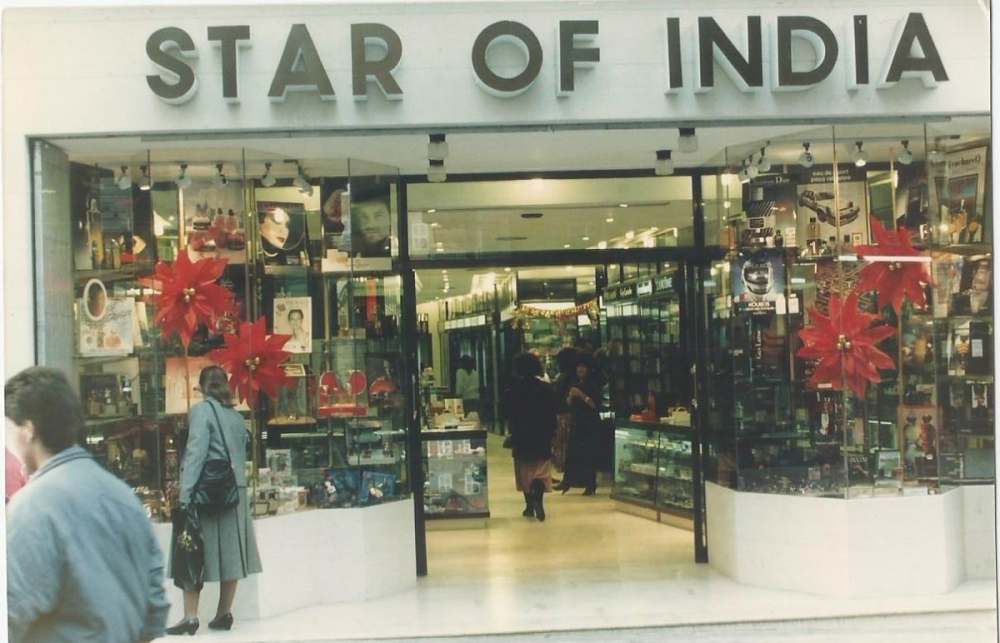

When my grandfather was forty years old, he came back to settle in Hyderabad and his eldest son, Mangharam, took over the business, which by then consisted of several small shops in various parts of Europe, Africa and South America. My uncle Mangharam found the business too scattered and diverse and started closing some. He kept a few and the main outlet was his store Star of India, in Gibraltar. In time, he sent for my father to join him there and they opened another shop for my father to run, Hotu, which was my father’s name.

Our stores Hotu and Star of India stand on Gibraltar’s Main Street, on either side of the Post Office

My father and his new-fangled ways

In 1936, at the end of his first three-year stint, my father went back to Hyderabad and his marriage with my mother was arranged. Having lived away from home and experienced life in a distant foreign country as a bachelor, he was of the opinion that a married couple must have their home together and he announced that he would be taking his bride back with him to Gibraltar. Being of a younger generation, he had these new revolutionary ideas, and luckily got his elder brother’s support to do so.

My mother, Rukmani, a rather timid person who had never been out of Hyderabad before, was soon to become the first woman in our community to join her husband in Gibraltar. It was 1936, a time when most of our women had never been allowed out of the house alone, not even to cross the road. She must have been excited and a bit nervous about going.

To live and work in a foreign country, you had to have a work permit and each store was issued a limited number. Women were not expected to work, so it could not be imagined that a woman would be issued a work permit. I have heard that my father and Mangharam crossed the border from Spain and sneaked my mother into Gibraltar dressed as a man.

My mother was a great reader and she had an educated, analytical mind. She would have made a good lawyer, like her father and brothers. Though from an educated family, being the eldest daughter she had to stay home to help in taking care of the household every time her mother had a child, and ended up never completing her schooling.

In her first year in Gibraltar, she used to be alone at home almost all day. I remember her saying that all she did was cook and cook. The two stores had about eighteen employees between them and they all wanted Sindhi food so she would be cooking kadhi, rice, saibhaji and all those things for eighteen men every day. For other domestic tasks, she had help. Buses crossed the nearby Spanish border every day, bringing labour. She had a maid to dust, clean and do the laundry in huge tubs of galvanized iron, hanging sheets and clothes out to dry on the terrace. But my mother must have gone to the market herself, climbing down three flights of stairs and then back up again with all the provisions, and sitting down to wash, chop and cook.

Gibraltar in the 1930 and 40s

In those days in Gibraltar, there was no regulation about opening and closing times for a shop. Most of the business was done with ships that stopped there. Gibraltar was a fortress and belonged to the British and as it was the entrance to the Mediterranean and strategically a very important point, it needed to be guarded. When British navy ships stopped there, the sailors came aboard to shop. This usually happened at odd hours, quite often in the middle of the night. The moment a ship was sighted or a ship’s horn heard, the men all excited would quickly get dressed and run down the stairs to their stores. And they stayed there as long as the ship was in the port. My father told us that he often slept in the store, on a cot right behind the door. The moment he heard people approaching, he would be wide awake and ready to sell.

My mother spent lonely days, with no other women to talk to. My father was out most of the time, once in a while going with his assistant to the navy ship to deliver merchandise which the captain had bought. When on port leave, the sailors would spend their time shopping and drinking in the local pubs, sometimes roaming around so drunk that they had no idea where they were. Once, searching for a bathroom, they climbed up three flights and knocked at my mother’s door, and she sent them off, while they kept apologising all the way down about how sorry they were to have disturbed her.

When the laws changed and it became easier for owners to bring their wives, a few more Sindhi women came to live in Gibraltar. While my father and the other Sindhi shopkeepers mingled with the locals and spoke mostly English and Spanish outside the house, the women were from a very conservative society and had never socialised much. My mother did make friends with them and years later, when I got married and moved to Gibraltar and she came to help me during my pregnancies and deliveries, she knew those women and had a special bond with them from way back then.

Rock House, Karachi

In 1940, it was time for my parents to return to Sindh. My mother was expecting me and it seemed wise that she should be back home with the family. But the Second World War had started. My parents were lucky, they got a passage on SS Kemmendine, which had left from England and was bound for Rangoon via Gibraltar. Other Sindhi families also boarded this ship bound for India. When Kemmendine was torpedoed, the survivors were transferred to SS Tiranna, a Norwegian cargo ship which was also torpedoed and sank.

By great good fortune they were rescued and taken ashore. My mother was all bloated from being in the sea for five hours and, pregnant with me, was treated better than an ordinary prisoner in the prisoner-of-war camp. My father was suspected of being a Jew and came very close to being killed.

When my parents returned to Sindh with me some years later, it was not to the ancestral family home in Hyderabad. My uncle Mangharam had lived in Europe for a long time and his tastes had changed. When he came back to Sindh on a visit in 1939, he bought a large plot of land a little away from the Karachi city centre and built a large house for the whole family. With his allegiance to the rock of Gibraltar, he called it Rock House. In those days there was nothing across the street in front of our house. In time, it would become a very congested area.

Rock House, our home, was demolished about eight years ago. Till about ten years ago, members of the family were still there. Over time, some died, some left. There was a fire and it burnt down. Then somebody bought it, built a high rise and maximized all that space.

Rock House was a two-storey building. The whole front main entrance was built of a rich burgundy-coloured marble and there was a fancy wooden staircase going up. Mangharam built a swimming pool in the front yard. At the back was a big angan (courtyard), all beautifully tiled. The women of the family would sit there making papads in the afternoon. They would roll out the dough with their rolling pins and fling them up from where they were sitting onto large sheets spread on the cots or khatta as we called them. I remember them calling out to me as I ran around, telling me to go and flip the papads over so that they dried on the other side too. By evening we would collect them, ready to be eaten roasted, or stored for later. The angan was a place for the women and children. On Sundays we children—so many of us!—got massaged there. And the family gathered there to eat meals together. The system in a big family was that at meal times the men were fed first and then the women would eat what was left over. The menu was catered for the men, so occasionally the women would make a dish they liked but which was not to the taste of the men, just for themselves.

Rock House had four large apartments for each of the brothers’ families. Mangharam and Partaprai had the lower level and my father and Daulatram the upper. Each apartment had its own kitchen but for many years, only one kitchen was used and we had just one cook for the whole family. It was only as we children grew older and had different timings at school that our mothers opened up their separate kitchens to cook for us. Till then, our meals were all directed by their mother-in-law, with the eldest daughter-in-law in charge. Us cousins were very close—just like brothers and sisters. Actually, that’s what we called each other. We weren’t allowed to say we were ‘cousins’. We were a self-contained family, and had each other to keep us company. I think the idea was to stay away from the Muslim culture and not to lose our Hindu beliefs and tradition. We all gathered for prayers for Diwali in our big hall and sat on a sheet on the floor for our pooja, at the end of which each one got kharchi (a cash gift, spending money) from Dada Mangharam.

The gyaro paro stage of life

In those days, when a woman’s son got married, she sat back and let her daughter-in-law do all the work. Once a woman turned forty, it was her turn to sit on a khatta in the angan all day long and control things by giving orders. You could tell by what a woman was wearing—a gyaro paro, a long red skirt made with ajrak material and a white top—that she was in that phase of life. My grandmother, with four daughters-in-law, had been wearing the gyaro paro for a while. Like other women in that phase and station, she had a big natha, a heavy nose ring with a large ruby and a black thread that went into her hairline to hold the weight. She wore it all the time, even when she was asleep.

With four daughters-in-law, my grandmother had her favourites. Not surprisingly, the one who got the best treatment was the one who had brought a nice big dowry. She happened to be the youngest, and came from an aristocratic Bhaiband family, the Mahboobanis.

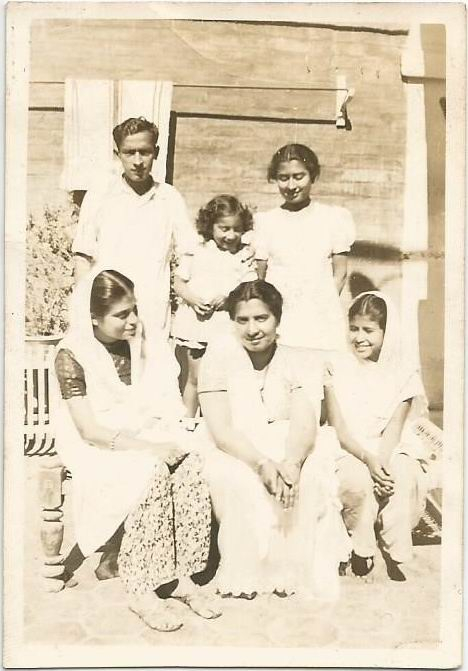

This photo was taken in Hyderabad, in the angan of my mother’s maternal home on a visit soon after we returned to Sindh. Standing: my mother’s brother Bhagwandas Sadhwani, me, my mother’s sister Nirmala who succumbed to typhoid at 18. Seated on a khatta are my mother’s sister-in-law Sati Hiranand Sadhwani, my mother and a friend who happened to be visiting.

My mother would not have had much of a dowry. She came from an educated family and her father, Tekchand Gulabrai Sadhwani, was a magistrate in Hyderabad and a well-known, influential person. They were more inclined to the Amil way of progressive thinking (Amils are another Sindhi community, more inclined to education and government service, unlike us Bhaibands who are invariably in business). However, she was an excellent cook and was given charge of the kitchen. In a home with twenty-five people, a lot of kitchen supervision was needed. Her special skill was making mithais, traditional sweets, and when there was a wedding in the family she would make huge thalis (platefuls) of mithai which would be distributed. I remember seeing her in the afternoon sitting in the angan, stirring a huge pot on a stove of burning coal. It took hours of constant stirring to get the mithai ready so her hands would be sore and I would feel sorry for her, but she was totally absorbed in getting it just right and, later, experiencing the satisfaction of everyone enjoying it.

The eldest derani, the wife of the eldest brother, had the keys to the family cupboards and was in charge, directly under my grandmother. With her daughters-in-law taking care of all the household tasks, my grandmother was always looking for ways to save and invest money. She would even skimp on food to invest in something. She would tell my dad, ‘Look for property!’ When he came home in the evening she would ask him, ‘Have you earned well today? Did you make money?’ And he would reassure her, ‘Yes! I earned lots and lots today.’ Some days he would bring piles of notes and affectionately put them in her lap. That was his way of making her feel secure and well-off. Since women did not have a source of income, we always tended to have a feeling of insecurity. There was always the urge to save so that we would have enough for tomorrow, in case of a crisis.

In our days, girls were not brought up to work and earn. The main concern was to get a daughter married and out of the house to her ‘real’ home. Thoughts of her marriage would begin right from the day she was born. My mother-in-law was already engaged to be married at the age of nine. At 13, she was sent to her in-laws and soon her childbearing years began. This was common across our community. I remember Dada Mangharam, my father’s elder brother who was like the boss, the head of our family of 25: the brothers, their wives and their children. He would tell us girls, ‘Hurry up and get married! Get married and get out.’ Girls took a dowry when they got married so families needed the money to give dowry. That’s why money was so important, I suppose.

But women were never encouraged to develop any kind of identity outside the family. Bhaibands always lived in joint families. The mother-in-law kept her eye on her daughters-in-law. It was their duty to do the work of the house and to serve her. As a result, Bhaiband women had to lead very disciplined lives. In one of the places I lived as an adult, I had a neighbour of my mother’s generation who would tell me about how her mother-in-law did nothing but sit there, watching her like a hawk. She and her husband did not even have privacy in the bedroom and were expected to sleep with the door open. She had children but when she tried to hug and caress them, her mother-in-law would taunt her, ‘Stop it! Is that all you are going to do all day?’ The only entertainment, the only reason for a woman to leave the house was when there was a death in the community. She would then be obliged to attend the marko, a ceremony held four days later, and to visit the gurudwara daily for twelve days. So when her mother-in-law left the house, she would fling off her dupatta and prance around for a bit! And then she would pick up her children, swing them up in the air and hug them and squeeze them as much as she wanted before her mother-in-law got back. My grandmother was not such a despot but she did control her daughters-in-law in her own way and excessive display of emotion was definitely frowned upon.

Amma refused to mourn

My grandmother was deeply attached to my father. In 1940, when the news came to Hyderabad that SS Kemmendine had sunk, families whose members had been on board went into mourning. However, Amma refused to go into mourning, to sit on the floor and moan and wail as she was expected to. She kept saying, ‘Hotu will come back. I know I will see him.’

She found out about a fortune teller who lived nearby and sent her eldest daughter-in-law and her granddaughter Gopi to her. The woman told them that she could see Amma’s son. Next to him she saw a lady wearing white clothes with a baby next to her. They came back to Amma, overjoyed. They had not known that my mother was expecting. Amma clung to this piece of knowledge and it gave her strength. My father was eventually able to send a message to his elder brother who was in Gibraltar telling him that they were safe and now had a baby girl.

Sadly, the news came too late for my grandfather. Overcome by grief, he had lost his memory. When my father eventually returned home, he would sometimes say to him, ‘Do you know where Hotu is?’ And ‘Have you seen Hotu?’ There were times when his memory returned fleetingly and he would say, ‘Oh Hotu! You are back!’ but then it would go again. This must have been heart-breaking for my father, his primarily motivation to survive had been to come back home and see the joy on his parent’s faces at his return. Two years after we returned home my grandfather had a heart attack and died. I was four when we came back and do have a faint memory of sitting on his lap.

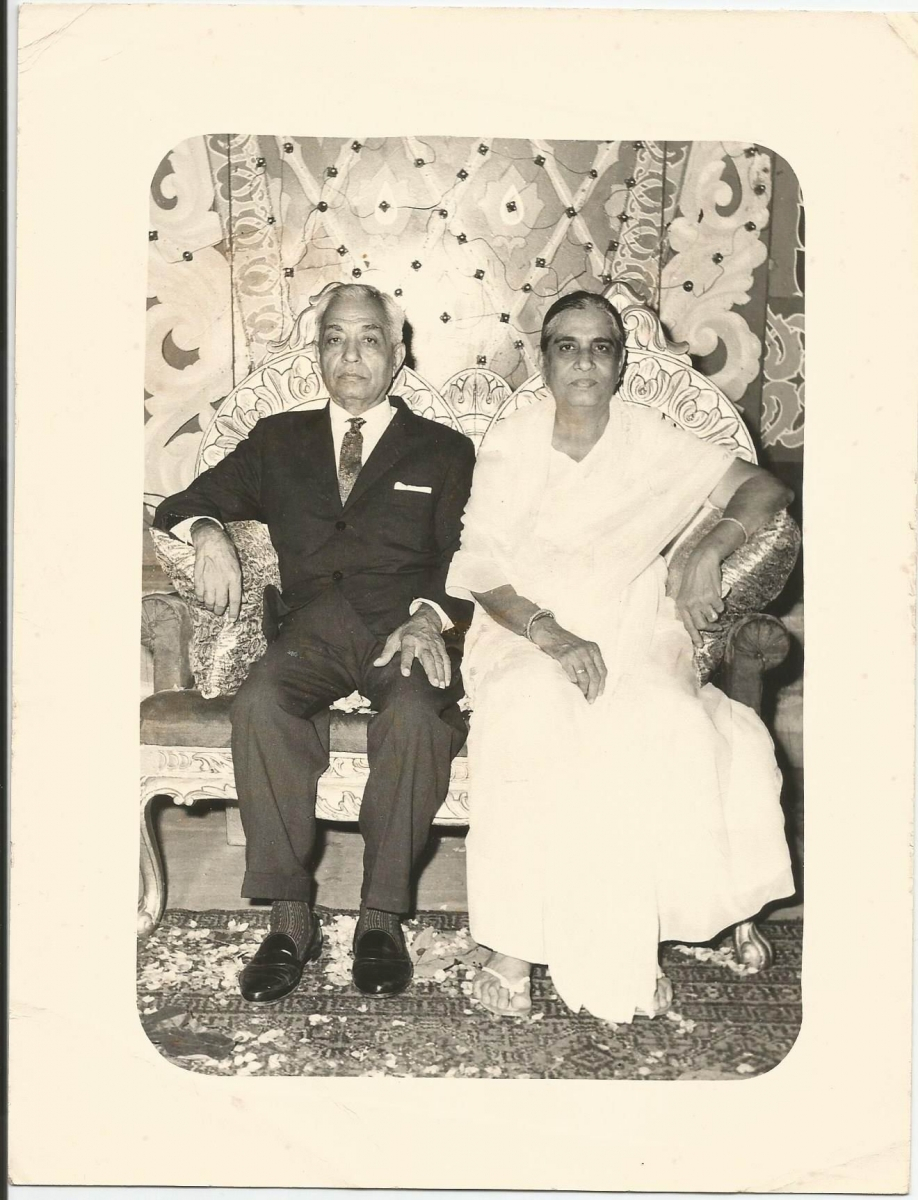

My in-laws, Naraindas Basarmal Bhojwani and Rukibai Naraindas Bhojwani

My grandmother continued to run the household, as she had always done. It could be that living on her own without a man all the years that my grandfather was away had given her strength and independence. So her status did not change after she became a widow; she continued to be the boss. It was this way with most of our Bhaiband matriarchs. Years later, my father opened a company in her name, Isar. I suppose her sisters-in-law and others of her age called her by that name. For us she was just Amma. About three years after Partition, Amma passed away.

Partition

It so happened that many men of our family were in Hyderabad at the time of Partition. During the Second World War, families had got separated. There must have been some who never came back home, and others who, like my parents, had survived all kinds of hardships and wartime escapades. They were now back in Sindh, enjoying being at home. When the rumours of Partition started, people started packing up and leaving, taking their families away from Sindh and moving to the places where they had their businesses or to a safe country. Daulatram and his family had left earlier on, to establish a business in Bombay and were not there during Partition but my father and Mangharam decided to stay on in Karachi with their families. It was their home, why should they leave?

We had malis (gardeners) and drivers and a chowkidar (security guard) at the door and they were all Muslim and we were comfortable and felt safe with them. My father had many dear Muslim friends too, and never feared them. However, there were people from our community who felt that Muslims were hot tempered, angry and vengeful. There was quite a large section that didn’t like Muslims at all. They were all right with them at a distance but didn’t like to deal with them. I remember my mother’s parents staying overnight with us. They had left their home in Hyderabad and were moving to Bombay. My grandfather, Gulabrai Sadhwani, would not even drink water in our house because, as he told my mother, all our servants were Muslims.

Most of the Hindu families fled with whatever they could carry, leaving their homes, businesses and money and arriving in cities across the new border as refugees. My future in-laws, too, left. They were the well-known Karachi jewellers Bhojwani Brothers, a very wealthy family with a lot of gold, diamonds and silver jewellery. They left everything behind and moved to Bombay. I was told how one of my husband’s uncles would go to the airport every day, taking one of the family children with him, and put him or her on a plane. At the other end, someone from the family would go to the airport every day, not knowing what to expect, and bringing home whoever had been sent. My husband was 12 and he remembers being left at the airport, where he had to wait until there was a seat available on a plane to Bombay.

Around this time, our family bought an adjacent plot of land behind our house. I think it came up for sale because the family was leaving to go to India. Now we had a huge garden with swings and lawns and one less reason to be out in unsafe areas.

We were Hindus who stayed on

I do remember that there was a lot of rioting, looting and killing. Women were being raped and burnt, and their husbands killed. There was a violent incident in the house behind ours and my father had to intervene. We were protected because of a close friend of our family, a very powerful lawyer in the new government of Pakistan. He was A.K. Brohi, my mother’s brother’s best friend. My mother’s brother, Hiranand Sadhwani and he had been at law school together in Hyderabad. When my uncle was leaving Hyderabad, he told Brohi, ‘My sister is staying behind. Take care of her.’ And Brohi said, ‘Don’t worry. She is my sister too.’ So that day when there was this crisis in the house behind ours and an old man was being beaten up, my father went and rescued the family and hid them in our house and called Brohi for protection. After that, we had the Pakistan military guarding our house 24 hours a day for several months. Brohi was a family friend and visited us often, and so was Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, a friend from Hyderabad and another influential Muslim connection. We were all Sindhis and shared the love for Sindhi music, poetry, culture and our Sufis.

In all the years we lived in Pakistan, it never seemed particularly dangerous, though we were under constant surveillance, being a minority. And we were conscious that, being the only prominent Hindu family, we stuck out like a sore thumb, with our enormous house of marble, a swimming pool and huge garden. Muslim refugees who had arrived in Pakistan looking for a better life for themselves felt anger and resentment with our businesses and carpet factory.

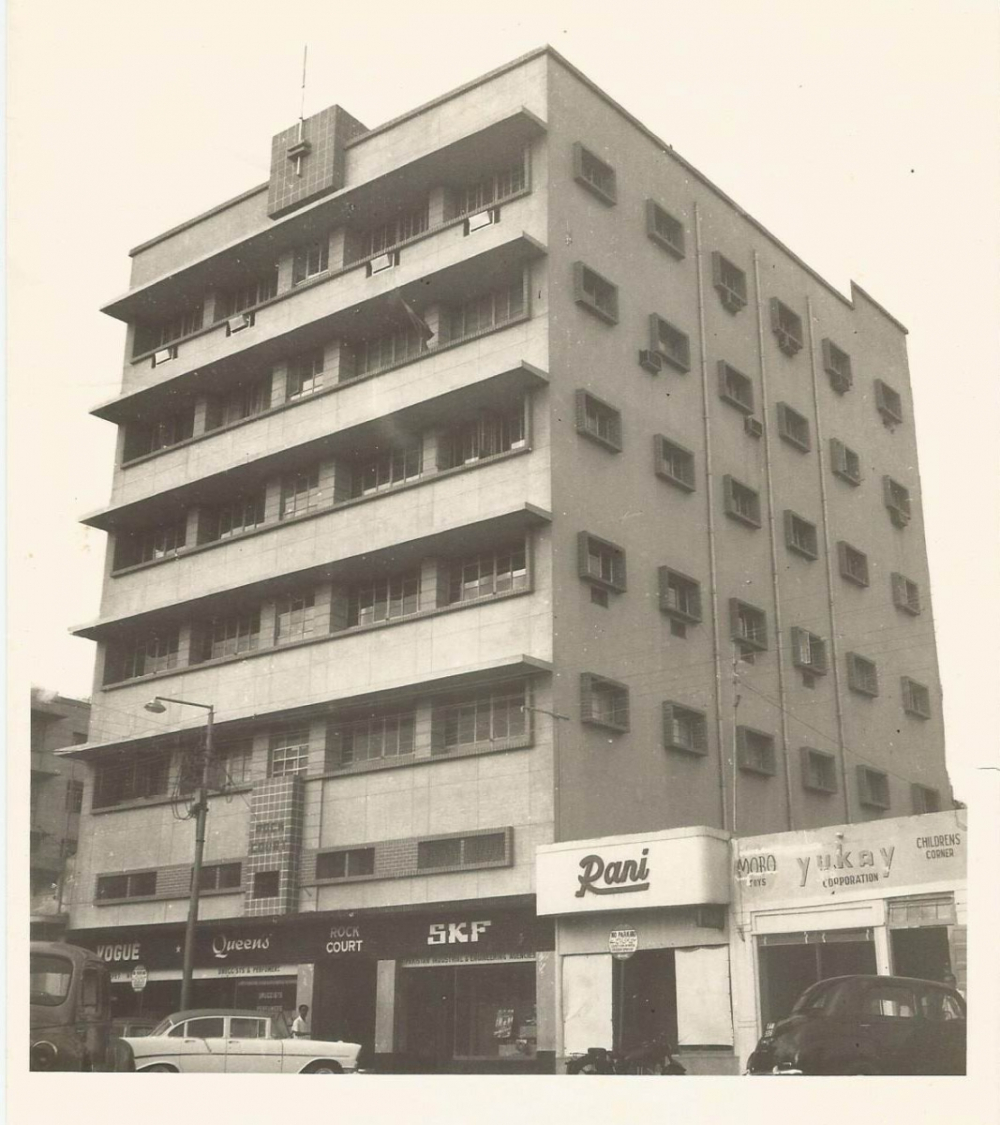

This office building, built by our family, stood on Victoria Road, Sadar, Karachi. On the ground level was our carpet store Vogue which was our flagship business, a perfume store called Queens and a Swedish company, SKF, for which we had the sole agency for all of Pakistan (in those days it was East Pakistan as well as West Pakistan). On the higher floors were offices of foreign companies including consumer goods companies, an American foundation and another SKF office.

People would walk past our house making loud threats. We had iron grill gates and I remember seeing men walking outside with stout sticks calling out, ‘Hindu people! We’ll come and get you out of this house!’ Many times I saw my father go out and talk to them diplomatically to calm their anger, but I'm sure it must have been quite tense till they put their sticks down and turned around and left, invariably threatening to return. He paid the price for being constantly under stress and carried the burden for us so we could live in safety and luxury. He faced threats and all kinds of very difficult situations, never showing any trace of his troubles, hiding everything from us, his family. Out of these circumstances he learnt to make many influential friends who protected us. He came to be well known and well-liked in spite of our religious differences. They just knew him as ‘Hotu Bhai’. We children grew up not fearing anybody or anything. When going to school if none of the family cars were available, I would just get into a rickshaw or a local bus. My mother would worry but we never felt unsafe in Pakistan after the initial looting and rioting settled down. There was no apparent fear of physical threat on the streets but in many subtle ways we were reminded we didn't belong here. With the Hindus mostly all gone, our friends were Muslims, Christians or Parsis, but their religion was of no consequence; they were just our dear friends.

The upheaval in the two counties had worsened the poverty and scarcity and there was a constant threat of thieves which had nothing to do with a religious or political conflict. In well-off homes, everything was kept locked in closets and in trunks under the beds. That’s why the women of the family carried bunches of keys. We didn’t trust our servants. And burglaries were common. The thieves rubbed oil on their naked bodies and in the middle of the night would sneak in quietly to rob, the oil making them slippery and difficult to catch if spotted. I remember my cousin Ram once saw a thief right next to his bed in the dark. He leapt up to grab him but the man ran away, jumping over the wall of the house and escaping.

Apart from good clothes and expensive things, Bhaiband women always had their jewellery. They wore their gold and diamonds and loved to collect more and more. For a woman, that was her wealth. In those days, there wasn’t much banking and in any case, people didn’t understand banking. It felt a bit like somebody else was in control of your money. A married woman always wore bangles. The idea of giving jewellery to your daughter when she married was to give her security. So if she was ill-treated or fell on bad times, she had some security. It was quite common when a man suffered business losses, or if he wanted to quit his job and set up on his own, that his wife would offer him her jewellery to sell. Jewellery was very beautiful and a sign of status. It was a good business to have and there was always demand for it, which is why my husband’s family business, Bhojwani Brothers, had been so prosperous.

As time went by, Pakistan started getting more conservative. Women were wearing burqas—which was totally foreign to us. My cousins and I kept up with our nice clothes. We studied at the Karachi Grammar School, a British school, and wore dresses.

One of my cousins, Mangharam’s daughter, had married an Amil boy who was living in Bombay. His parents lived in Hyderabad and the match was arranged there. After their marriage, he took her to live in Bombay which to us in those days seemed as glamorous and fast-paced as London. Because of the convenience of having her to stay with, we spent our Christmas holidays there. I think our parents kept a foot in the door to make sure that we girls married Hindus. They stayed in touch, kept contact with distant relatives and introduced us to different Sindhi families.

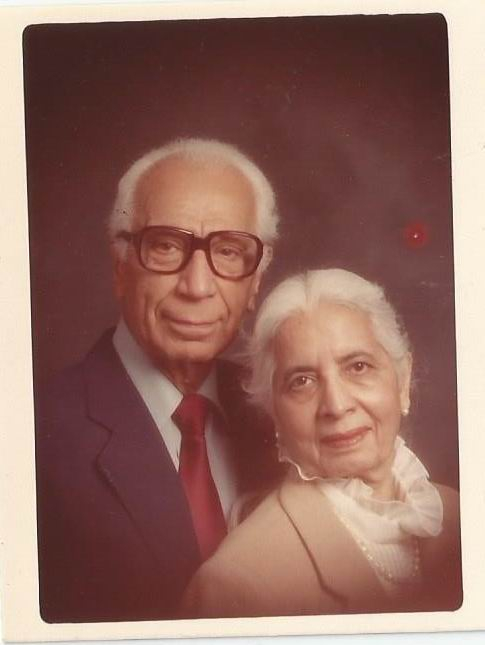

My parents, Rukmani and Hotu Khemchand Mahtani, c. 1985

Gibraltar in the 1950s and 60s

In 1957, after I finished school, I went to California as an exchange student. On my way back home, my parents received me at Southampton where the ship docked, and the three of us toured Europe together. At the end of it, my father took us to Gibraltar. Our family had business holdings there which were managed by our employees and every few years one of the brothers would make a visit to check on the accounts, the stocks and to stay in touch with the loyal employees.

We stayed in Gibraltar for about three weeks. My parents had lived there years ago but still had many friends there. We were invited for parties and I got to know some of them. It was at this time that Santu and I first met. He was on his first Sindhwork trip and was looking after our shops.

My uncle Mangharam had met him in Bombay and took to him at once. He offered him a Sindhwork job as soon as he finished college. Santu was keen to study more but because of the family situation after Partition, he had no choice. His whole family, so well off in Karachi, had arrived in Bombay without anything and for quite a long time they survived on the largesse of the few relatives who had got there before.

My father-in-law was Nariandas Bassarmal Bhojwani and he worked together with his brothers. That’s the way it was in those days: in every joint family, the brothers worked together. My mother-in-law, Rukibai, had been a Hathiramani before marriage, another of the old aristocratic Bhaiband surnames. She had four daughters and then five sons and my husband, Santu, is the second son.

They lived together in a big house named Chandhiwalla Building in Dadar. They did get back into the jewellery business but without capital, and working against the already established jewellery cartels in Bombay, it was difficult. They realised that they could no longer maintain the standards of a joint family and gradually formed separate family units, each trying to make ends meet and get on with their own lives, and the joint family of so many generations broke up.

Santu was young, hardworking, and fit well into our family. He was not considered just one of the staff, being different from the rest; he was one of us. He had been handpicked by my uncle Mangharam with the idea of grooming him to take charge so that the brothers could take it easy and have someone trustworthy to manage the Gibraltar business.

We got married in Bombay in 1961, on Santu’s first visit home at the end of his first Sindhwork contract, as per Bhaiband tradition. But it was not a traditional Bhaiband wedding where the couple are introduced to each other a few days in advance and large dowries are handed over. Our parents had given us time to get used to the idea and develop our attachment to each other. And my mother-in-law was not after a dowry. Her daughters were already married and she didn’t have to collect money for their dowries. So my parents just gave us large gifts of cash which kept us comfortable with the good rates of interest we had in those days.

I was 20 years old and for me the Bhaiband life in Gibraltar was a new world, one in which what was important was how much money you had and what you were worth. I moved in with Santu to the firm’s house where the employees lived. We were there while our house in La Linea, just across the Spanish border, was being constructed. The flat was big and was run by the wives of the two managers.

They supervised the cooking and in the evenings we would all eat together when the men came home from the shops. One of the daily routines I remember was that every evening they had a hairdresser coming to the house. The women would get rollers put and when their hair was set they would get ready and the maid would serve them tea. They would then go down to Line Wall Boulevard where they would sit and chit-chat with the other Sindhi women until it was time to come back home for dinner. They invited me to join them and I did try going a few times but they were much older and in those days I spoke mostly only English, so felt out of place. Instead, I would buy a magazine from the bookstore and sit on the terrace and read by myself. I also spent time with the Pohoomals who at that time had three unmarried daughters with whom I got along with rather well. The eldest one married a Sindhi, the manager of Bhojsons in Gibraltar, and so our friendship got even stronger. We still keep in touch.

My uncle Mangharam was keen that I join the business to keep busy and not sit idle at home, and I was used to working as I had always gone to our stores in Karachi to help out after school. Our two stores specialised in French perfumes and cosmetics and also fine cashmere sweaters and silk stockings from England. These items were in great demand by the tourists and the naval officers as gifts to take back to their fashionable ladies. Gibraltar was a duty-free port making it tempting to shop a lot. But our staff resented having the boss’s daughter around. In any case, they all had their work laid out so there really wasn't much I could do except rearrange and sort out the merchandise. This was not to my taste as I needed something more productive, so I quit.

About a year after I came to Gibraltar, two more young men got married and brought their wives with them so I had company of my age and station. Our generation was quite different from the older Bhaibands. Before that it was just the older women and they would mostly sit and gossip. Their husbands’ timings were terrible, money was just not enough, the children were becoming difficult, the newly-married younger generation had turned out so strange…there was quite a lot to complain about! Also, some of their husbands were cheating and everybody knew about it. Having lived here as bachelors, they had girlfriends across the nearby border in Spain. So maybe they talked about that too.

Once a week, us younger ones would get together to play rummy. And then there was the dressing up, the shopping, and an underlying competitive feeling to all that we did. This was our little world on the Rock, an area of two square miles. When our friends travelled they would bring things from India and show off. Or ask each other ‘What did your parents send?’ and compare it with what someone else’s parents had sent. Then it became, ‘I got this from Hong Kong!’ and everyone wanted things from Hong Kong. Then French chiffons became fashionable. It went on and on. This was the life of a Sindhworki Bhaiband woman. When I look back, it surprises me how we managed to survive with so little intellectual stimulation.

Just because of who I was

In Gibraltar, we had a strict social hierarchy, and though I had not married a rich man I was included with the in crowd without doing anything, just because of who I was. My family had been here for generations and were owners, not employees. There was this unspoken feeling that the ones who were not from Hyderabad or Karachi, the ones who had come later and their families belonged to Sukkur or Sehwan or other places in Sindh, were just not equal.

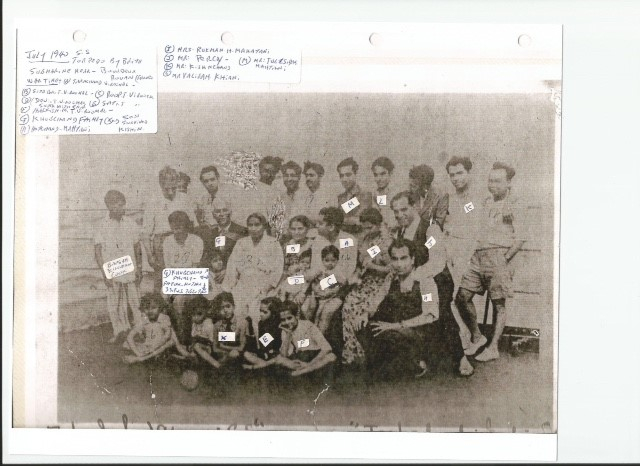

1940: A shipboard photo of the Gibraltar Sindhworkis, delighted to be heading home to Sindh. Many of them lost their lives when the Kemmendine sank. My mother, pregnant at the time, is seen third from the right, looking down, perhaps fixing her sari.

The oldest to settle in Gibraltar were the Poohumals, Dialdas, Khemchand, the Khubchands and a few more families. Kishin Khubchand had been a little boy on the Kemmendine when it went down. He lost his entire family that day and my mother took him under her wing and cared for him like a son. He was and still is like a brother to me. There was also the Carlos family. We all had our stores on Gibraltar’s Main Street. Carlos is of course a Spanish name; many of the early Sindhis took up local names. Nobody could pronounce my uncle Mangharam’s name so he had been Don Miguel to the locals.

I was somewhat pampered in Gibraltar because of surviving the shipwreck. All the Indians who were on that fateful Kemmendine voyage were from Gibraltar. In the prison camp, people knew that my mother was expecting and they would give her little gifts from their cigarette money. She in turn would ask the German guard to go and buy vegetables and she would cook for them. This was something they all remembered with warmth and gratitude. I was born there and the only baby in the camp. Anywhere I went, they reminded me that we had all been together in occupied France, and this created a special bond between us. My friends who were new to Gibraltar would wonder why I was getting special attention. Even Kishin used to tease my husband, telling him ‘I picked your wife up in my arms before you did!’

As time went by

As time went by, our families had children and the children grew up. We formed a little India Club where we’d have birthday parties and celebrations. We all became very close, and our children too. About ten years after we got married, my husband and I decided to leave and venture out on our own. We first moved to Canada but that didn’t work out, and we chose to settle in Las Palmas, Spain, where there was a fair-sized Indian community and the lifestyle was what we had got used to. We opened a perfume store, a business we understood, and ran it for 25 years.

The Sindhi Bhaiband women had a routine of taking care of the children, sending them to school and cooking two meals for the family. Here it was a custom to have two main meals. Fortunately it was possible to get Spanish women as house help for the heavy cleaning. After lunch was 'Siesta' where everyone rested, after all, we were in Spain. Then the men would leave for their evening shift and the women, depending on their circumstances, would either stay at home with the children or go to satsangs (religious meetings) or play cards in their individual groups. I somehow did not take to these activities and spent the evenings with my three children and seeing to their homework. Their schooling was in Spanish but I wanted them to be fluent in English, more of a world language, and the one I was most comfortable with.

As our children graduated, the two older girls left to study in Canadian universities and our son went to a boarding school in England. Many families sent their sons to England to better prepare them for the business world. Now I had time on hand and, longing to be productive in some way, decided to join my husband in our perfume store. We worked together for about 13 years until one day a potential Sindhi buyer approached us with the offer to buy out our business. Santu was tired of retail, and our children had grown up and left home. It was time to wind down. We negotiated and ended up making a deal and selling. So in 1996, after 25 years in Las Palmas, we began our move to the US to be closer to our children.

We often think of our years spent there with sweet memories, but are happy here in our comfortable home and, with our two daughters just two minutes away and two grown grandchildren to relish, we are all together again.