In the Kashmir Valley, where the crisp morning air carries the aroma of freshly baked bread, the kandur (traditional baker) begins his day long before sunrise. As Muslim devotees rise for Tahajjud (the voluntary pre-dawn prayer) smoke billows from kandurwaans (the baker’s shop), enveloping Srinagar’s dense neighbourhoods in an ashen haze. Inside the bakery, a tandoor (a large clay oven) glows with embers, its heat preserved by the damgeer (an iron lid). It was under such a damgeer that fourteenth-century mystic Lal Ded found refuge, leaping naked into the tandoor only to emerge miraculously clothed in flowers.[i] Ever since, kandurs believe their craft is blessed with baraka (divine blessing) granted through Lal Ded’s prayers and gratitude for the tandoor. The tandoor, a derivative of the Persian tanur or oven, was likely introduced to the region around this time, through the ancient Silk Route that connected Kashmir to Central Asia and Iran.

Kandurwaan, a place for community interactions. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

While similar bakers exist across Pakistan and Southern Caucasus, bread-making in Shehr-e-Khas transcends mere baking; it represents the rhythm of life, the coming together of communities. Folklore and literature have long captured its cultural significance—such as Mahmood Gami’s verse Chaytmo chini pyalen chai hato[ii] (1855; in which a woman offers tea to her beloved) or Zareef Ahmad Zareef’s satire Kandur Kaar (2015), both symbolising how the shared warmth of tea and bread remains central to Kashmiri identity.[iii] For most families, a morning without a visit to the kandur is unthinkable, each mohalla (neighbourhood) complete with its exclusive kandurwaan.

In Srinagar, bread serves as a complete meal enjoyed throughout the day, paired with tea or other accompaniments. Placed beside Gami’s delicate Chinipyala (a handleless bone china cup), the khos (a rare bronze vessel favoured by Kashmiri Pandits[iv]) or an ornate samovar (a traditional tea urn), a wicker basket full of bread, such as lawasa and girda, still adorns traditional breakfast tables in Kashmir’s villages. While modern crockery has replaced these vessels in urban areas, bread, with its more than fifteen variants, remains integral to daily life from dawn until dusk. The colourful Crewel embroidery bags that carry these breads transport not just food but a tradition that unites Kashmiris across socio-economic divides.

The Setting

A kandur’s shop is typically located on the ground floor, its modest facade, often without a signboard, belying the warmth within. As one approaches a kandurwaan, a common sight is that of an elderly man, clad in a pheran, puffing on a hookah, sitting in front of a wooden galdaan (cash box with a slit to deposit money through its lockable lid). Along the shopfront, a recessed wood counter displays the baked goods through its glass panels, its shelves and drawers sometimes lined with newspapers. A small steel or wooden handrail, barely 4–10 inches high, marks the shop front boundary. Customers gather here waiting for their turn to give their order to the vaste (lead baker), whose hands move swiftly to keep up the pace. Traditional shops had shelves extending to the ceiling for heat retention, with windows used for transactions.

The modest wooden facade of a kandurwaan. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Two level floors in a typical kandurwaan. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Counting breads for distributorship. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

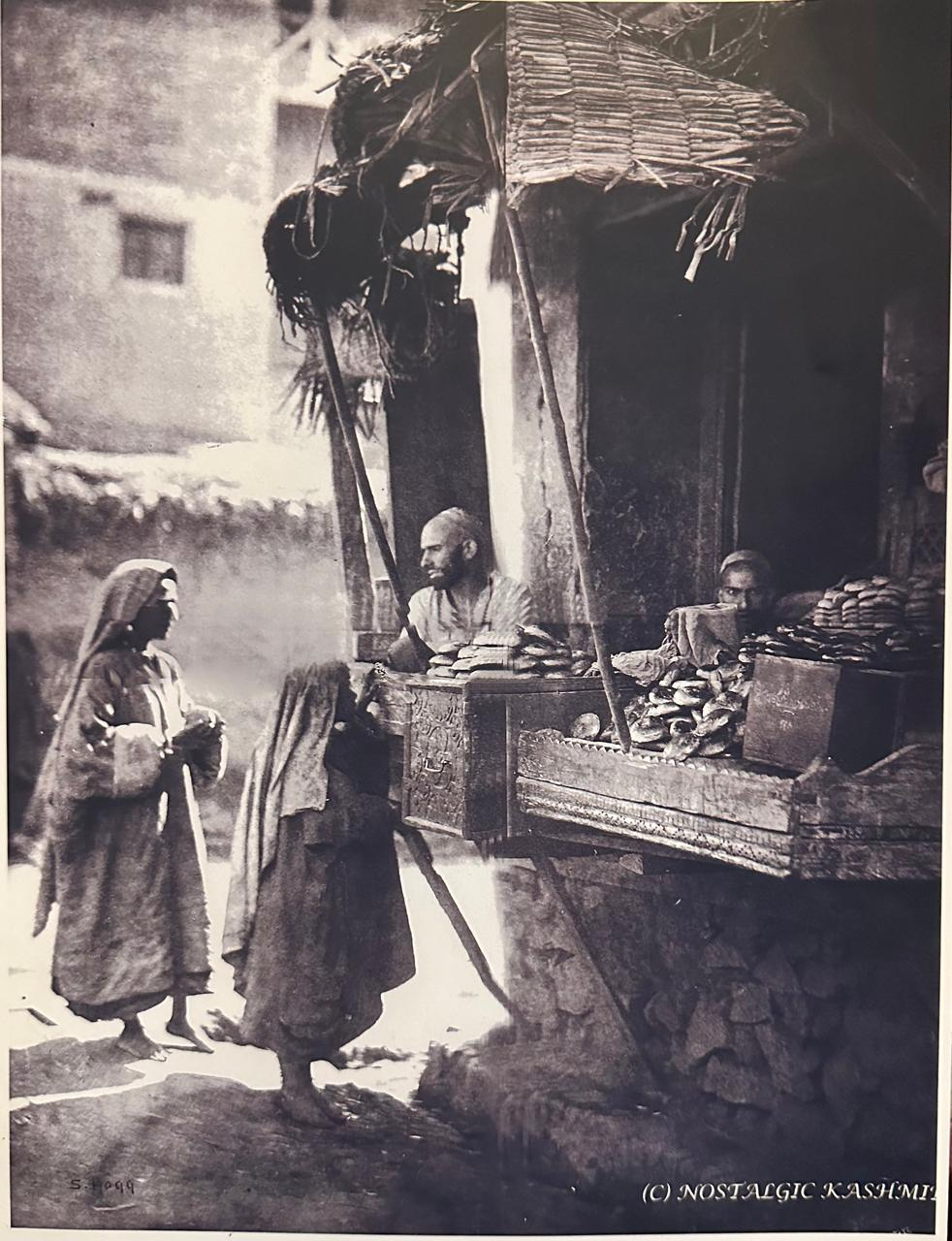

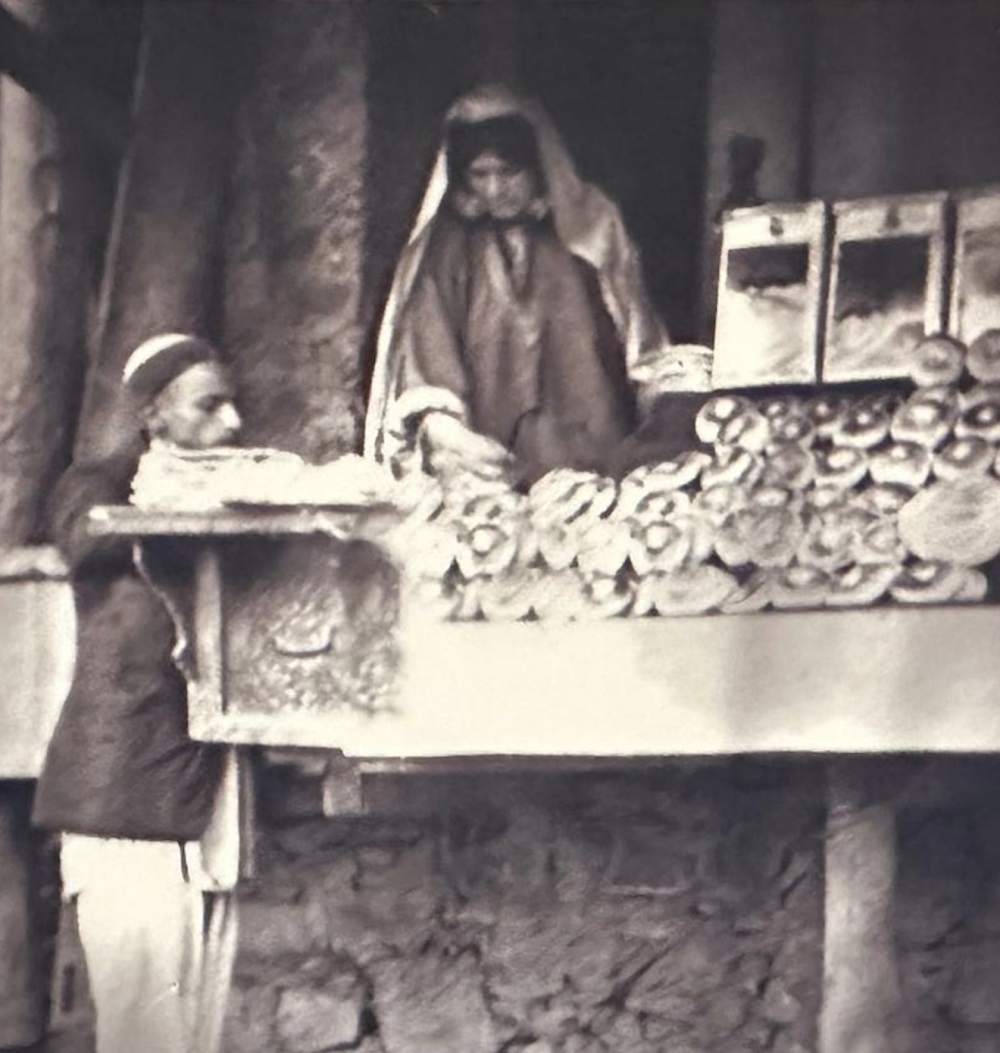

Historic documentation reveals these bakeries once featured handcrafted wooden panels and ornate plinth bands. Photographs by Captain S. Hogg (1917) documented the use of hatab bush (witch hazel) and reed mat (waguv) sun shades that are now increasingly rare.[v] Other images by R.C. Mehta (1940), Brain Blake (1957) and Hemul Del Terra (1932) show bread being stored in repurposed oil tins with glass inserts and sold in wooden carts and wicker baskets at markets and shrines.[vi] Such traditional facades and open-air sales methods have largely disappeared, though the basic function of the shops remains similar.

The Layout

A kandurwaan is divided into a sitting area and a recessed workspace for bakers. This layout aligns with different stages of breadmaking, as aptly captured in a historic watercolour from the Album of Kashmiri Traders (c. 1860), part of the British Library archives.

Photograph by Captain S. Hogg, 1917. (Picture Courtesy: Nostalgic Kashmir)

Photograph by R.C. Mehta, 1940. (Picture Courtesy: Nostalgic Kashmir)

The sales area typically contains a wooden till (galdaan) and a low wooden platform for displaying bread varieties. The central clay tandoor is positioned nearby with its lid (damgeer). The work area is traditionally positioned approximately four feet below the customer area, with bakers working in designated stations. One station is for preparing dough on a wooden counter (takhte), while another is dedicated to managing the baking process. Tools include a scraper (khurchan) for cleaning, skewers for retrieving bread and a traditional balance for weighing dough, which has largely been replaced by digital scales in modern shops. A secondary oven (matte) serves for storing half-burnt firewood (sokhte) used in the main tandoor for lower-temperature baking. While modern ventilation systems, including exhausts and chimneys, are now common, walls still accumulate soot. Maintenance includes periodic application of fresh mud coats (lyiwun) every few weeks, with open entrances providing additional ventilation.

The Process

The bread-making process begins the night before baking. The initial step involves creating the mayye or zyevrun, a pre-ferment made by combining maida flour and water (aedrawun). Left overnight, it expands to form a paste-like consistency. A small portion of this paste is mixed with more maida and water to form dough.

Wasta rolling dough balls. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

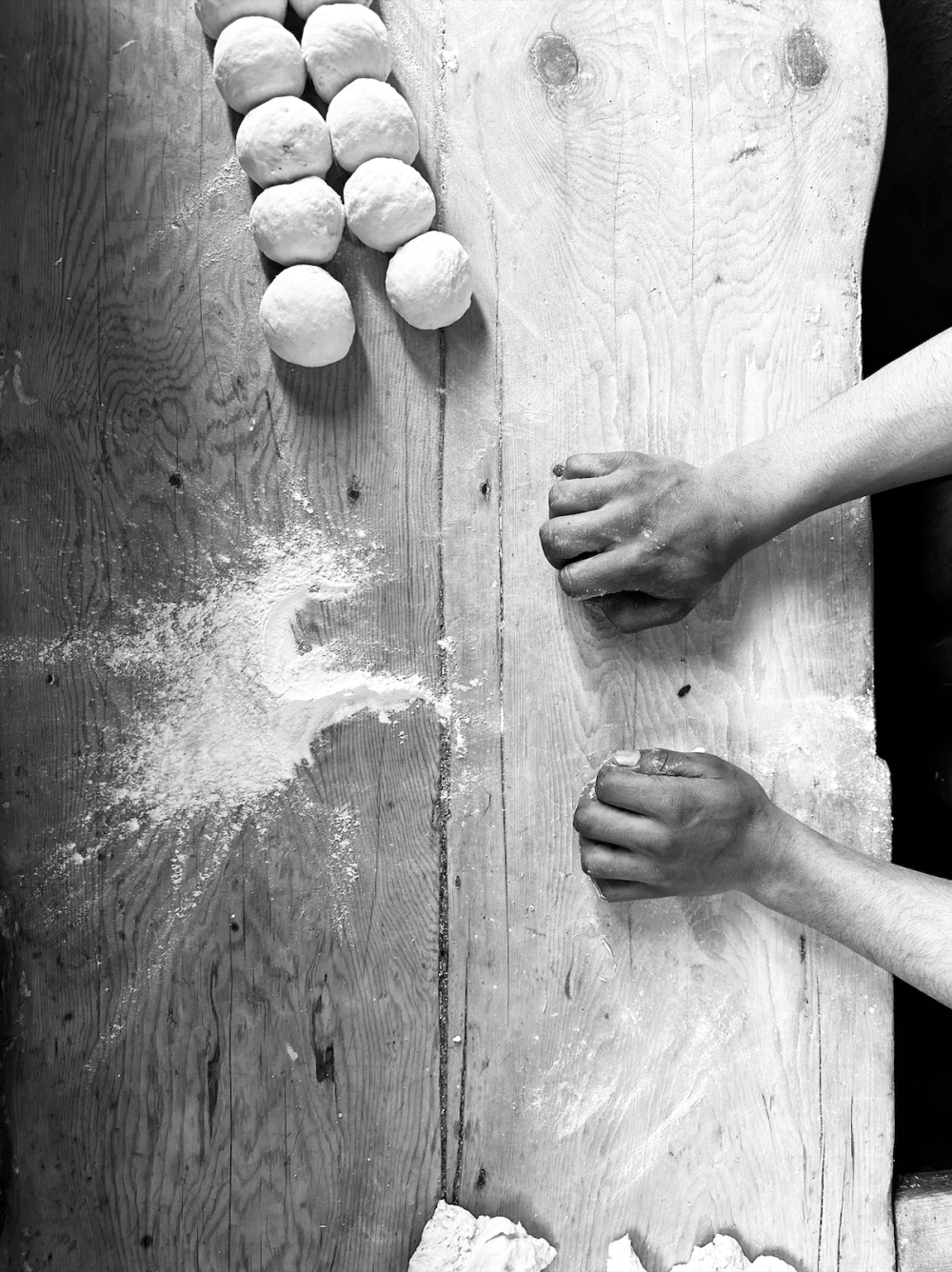

Preparing the dough balls on an elevated takhte or wooden board. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Uniformly sized dough balls kept awet by a cloth. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Flattening the dough balls for baking. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Crafting indentations on a flattened dough to prepare girde on a marble base. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Metal rods and girde in the glowing tandoor. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

A young apprentice plucking girde out of the Tandoor. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Golden brown girde with sprinkled poppy seeds. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

First thing in the morning, an apprentice retrieves apricot firewood for the tandoor and sweeps the shop, while a baker kneads the dough in a large copper pan (taev) for morning breads like girda, lavasa and gyev tschot. After a resting period, the dough is weighed digitally and rolled into uniform palm-sized balls. These are then arranged in rows on a sturdy wooden board (takhte) and covered with a damp cloth (tarpoosh) to maintain moisture. The dough is then flattened on a marble slate (devri), the baker occasionally dipping his fingers in milk before creating indentations on the surface of the dough. As the bakery slowly comes to life, the master baker (vaste) applies the flattened dough to the internal walls of the tandoor using either hand pressure or a cushion-like pad (ribde). Meanwhile, another baker, sitting cross-legged over the tandoor, adjusts the bread’s position with a hooked rod (seekh) and spatula (ramme) to ensure even baking. Firewood is managed using larger variants of these tools. Coals are removed using a T-shaped implement (narkash) to fuel the secondary oven (matte) or to provide heat for visitors’ clay fire pots (kangris).

This whole process, which churns out approximately a thousand pieces of bread, requires three to five people working in a synchronised manner, often family members with gender-based division of tasks—women preparing the dough or handling sales, men operating the tandoor and children delivering the finished product.

The Varieties

A Kashmiri tandoor operates continuously throughout the day, with different bread varieties baked according to the oven’s gradually decreasing temperature. At its hottest, flatbreads like tschot (made from maida flour, milk and salt) are baked until golden. A breakfast staple, they’re served with nun chai and butter. As the tandoor begins to cool, ghee tschot, made with generous helpings of ghee, is baked, commonly served with tea or rogan josh at weddings or during Ramadan. As the temperature drops further, the bakers move on to the thinner lavasa (similar to naans), served as wraps containing barbecued mutton or chickpeas. Then comes tsochwor (sesame-seed sprinkled doughnuts), usually had with nun chai or curd. Late afternoon is the time to bake kulchas, the sweet version to be had with nun chai, while the savoury variety, with peanuts or almonds, is served at celebrations or festivities. Khatai, a sweet kulcha, and mildly sweet sheermal flavoured with date milk are best enjoyed with kahwa. For special occasions, such as at weddings and engagements, bakerkhani, a layered, ghee-rich puff pastry, is served. Roath, another sweet, sponge-like bread containing dry fruits, is prepared for significant social occasions, such as childbirth or the arrival of a new bride, with the tradition of distribution known as Roath Khabar.

Lavasa and gyav tschot. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Tandoori kulcha. (Picture Credits: Taha Mughal)

Different regions in Kashmir have developed its signature bread varieties—Baramulla is known for its namkeen kulcha, Pampore for sheermal, Shopian for krip and Anantnag for katlam. These varieties often have extended shelf lives, making them suitable for transport to other regions. The expansion of kandur shops beyond Srinagar, in places such as Jammu, New Delhi, Noida, Amritsar and even the US, has created cultural extensions of Kashmiri identity abroad.

Today, kandurs are faced with several challenges, including rising costs, hygiene concerns and the declining interest among the younger generation. The economic pressure on the tradition is evident in the 100 per cent price hike in 2024, doubling the price of a girda from INR 5 to INR 10. Despite threats posed by inflation and new bakeries, the tandoor endures, possibly blessed by Lal Ded’s prayer for its eternal sustenance. Be it at the 200-year-old Batta Kandur in Ali Kadal or in Palhallan, where forty households still mould tandoors by hand, its fire remains strong[vii]. Beyond being a source of livelihood or sustenance, the figure of the kandur remains a symbol of continuity, shared identity and a lasting path to home—no matter where Kashmiris may be.

[i] Richard Carnac Temple, The Word of Lalla the Prophetess (Kashmir: Gulshan Books, 2015 [reprint]), p. 8.

[ii] Vinayak Razdan, ‘A study of Kashmiri love for Tea’, SearchKashmir.org, accessed on 26 March 2025, https://searchkashmir.org/2015/11/a-study-of-kashmiri-love-for-tea.html.

[iii] Razdan, V. (2020, October 12). A study of Kashmiri love for Tea. Retrieved from SearchKashmir.org: https://searchkashmir.org/2015/11/a-study-of-kashmiri-love-for-tea.html

[iv] Razdan, ‘A study of Kashmiri love for Tea.’

[v] Ajaz Rashid, ‘Waguv “A vanishing craft of Kashmiri heritage,’’’ Kashmir Scan Magazine, accessed on 26 March 2025, https://kashmirscanmagazine.com/2022/08/waguv-a-vanishing-craft-of-kashmiri-heritage/.

[vi] The access to the historic photographs was generously provided by Showkat Rashid Wani and Waseem Showkat Wani through their exhibitionNostalgic Kashmir. Interestingly, it was one of the historic images of a kandur found in their attic that inspired the father-son’s archival collectionof more than 19,000 historic photographs of Kashmir.

[vii] See: Upendra Kaul, ‘Koshur Kandur, Kandaer Waan and Tchot: A Kashmiri heritage,’ Greater Kashmir, accessed on 26 March 2025.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).