The cultural history of Lucknow is deeply intertwined with the artistic and aesthetic pursuits of its rulers, especially the eleventh and the last ruling Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah (1822–87). Renowned for his profound passion for the arts, poetry, music and dance Wajid Ali Shah differed markedly from his politically inclined predecessors, dedicating much of his reign (1847–56) to enriching the cultural heritage of Lucknow. An accomplished poet and dancer himself, he played a significant role in refining Kathak, composed thumri music and introduced grand theatrical productions like Rahas. Among his many contributions, the Parikhana stands as a unique institution, often misunderstood yet crucial in shaping Lucknow’s artistic identity. Despite his cultural achievements, his reign unfolded against a backdrop of political turmoil. In 1856, the British East India Company annexed Awadh, deposing Wajid Ali Shah on allegations of ‘poor governance'. Exiled to Matia Burj near Calcutta (now Kolkata), he nevertheless continued his patronage of the arts.

The Parikhana: An Academy of Performing Arts

Literally translated as ‘House of Fairies,’ the Parikhana was a sanctuary for beautiful and talented performers. Both as an artistic institution and in its physical manifestation, the Parikhana is well documented in archival records and recent scholarship. Contrary to its common perception as a leisure palace, the Parikhana functioned as an academy of artistic excellence. As an institution dedicated to the refinement of performing arts, it served as a hub where talented poets, musicians and dancers converged to create and perform under the patronage of the nawab. The physical space of the Parikhana, within the Qaiserbagh complex in Lucknow, reportedly embodied beauty and sophistication, with gardens, ornately decorated halls and specially designed performance stages. These elements coalesced to foster an atmosphere of creativity and artistic immersion.

An engraved portrait of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (r. 1847-1856), 1872. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

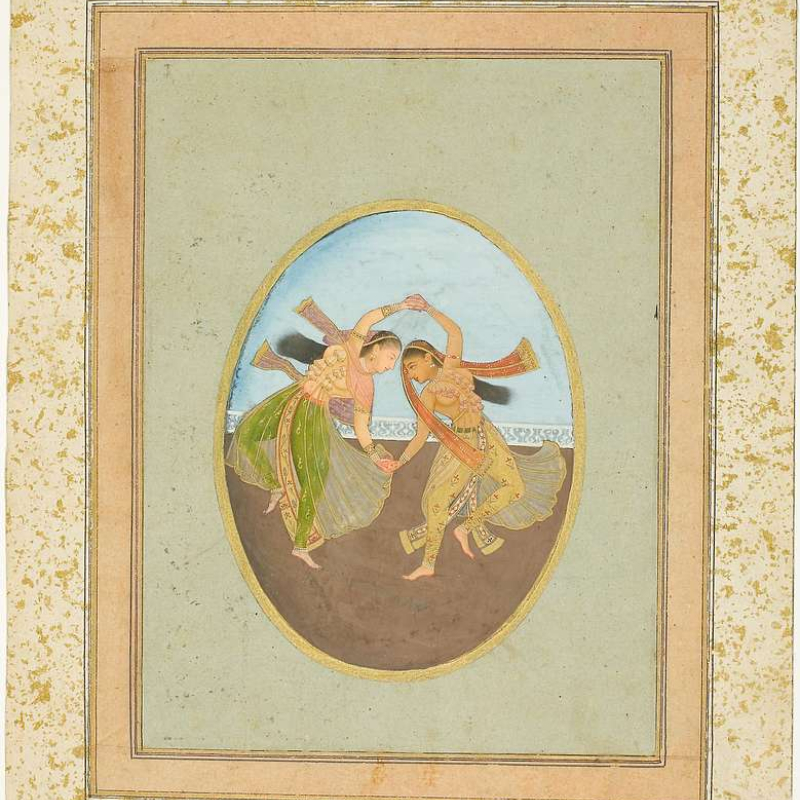

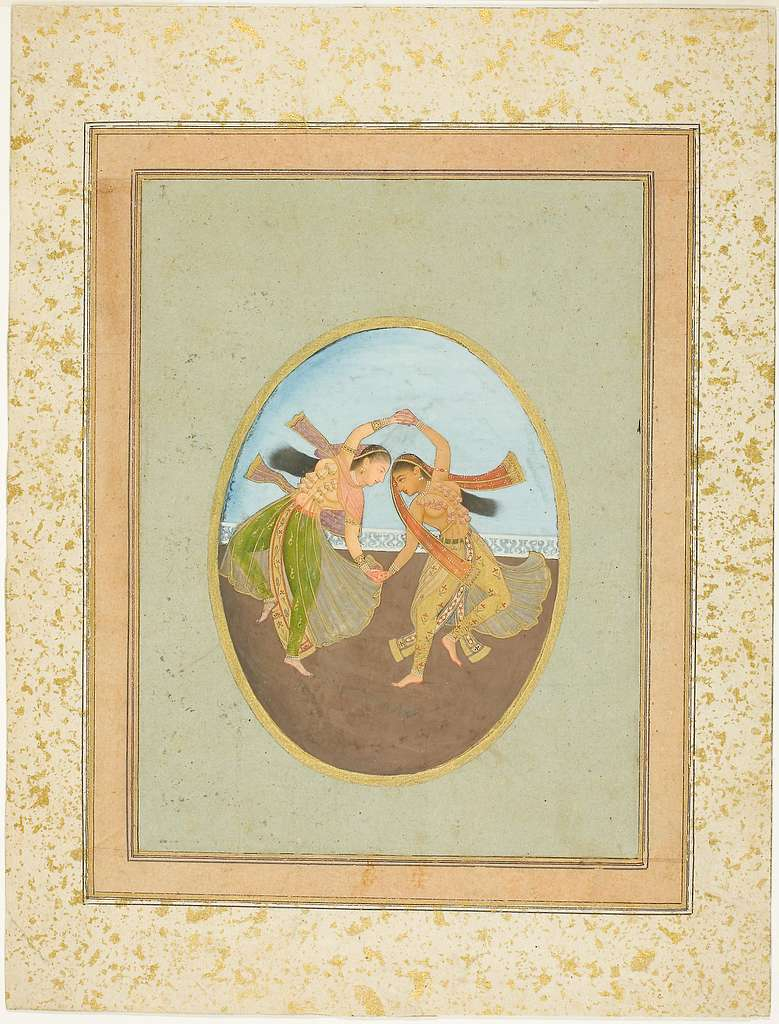

Two girls performing kathak, miniature painting, 18th-century. (Picture Credits: Art Institute of Chicago/Picryl)

Wajid Ali Shah was deeply influenced by Persian and Indian traditions of poetry and dance, and his vision for the Parikhana centered on establishing a space where creativity could flourish unfettered by rigid courtly norms. The Parikhana, therefore, functioned as both an artistic retreat and a space for the systematic training of performers, resembling an elite cultural academy. The Nawab personally oversaw its operations, acting not just as its benefactor but also by actively participating in its artistic endeavors; he wrote poetry, composed music and choreographed dance performances. Young women, known as paris (fairies), received rigorous training in classical dance forms, especially Kathak, alongside vocal and instrumental music. There was also a system of merit-based advancement within the Parikahana, rewarding the efforts of carefully exceptional artists.

One of the Parikhana’s most significant contributions to Indian performing arts was its role in refining the Lucknow Gharana of Kathak. Trained in Kathak, Wajid Ali Shah, a dancer and choreographer himself, emphasised the bhava (expressive) aspect of Kathak, incorporating delicate gestures, fluid movements and sophisticated storytelling techniques into the dance form. His influence helped transform Kathak into an elegant courtly art form that continues to be celebrated today.

The Parikhana also provided a platform for renowned musicians and composers to experiment with new ragas and compositions. Wajid Ali Shah himself is credited with composing several thumris, a semi-classical genre of Hindustani music that remains popular in Indian music traditions to this day. Poetry, too, flourished within the Parikhana, Wajid Ali Shah being a prolific poet who wrote under the takhallus (pen names) 'Qaisar' and 'Akhtarpiya’. His verses, often romantic and melancholic, including the poignant composition 'Babul Mora Naihar Chhooto Hi Jaye’, reflected his deep love for art and his emotional connection to his city and people. Many poets and courtiers in Lucknow emulated his literary style, ushering in a golden age of Urdu poetry.

Grand theatrical productions, including rahas—a dance-drama blending poetry, music and elaborate storytelling—emerged from the Parikhana as a signature form of entertainment under Wajid Ali Shah’s patronage. Such performances likely laid the foundation for modern nautanki and/or musical theatre in Awadh and beyond.

The Parikhana: A Sociopolitical Event

Wajid Ali Shah cultivated a remarkably inclusive environment within the Parikhana. During celebrations marking the birth anniversary of the 12th Imam, the palace would be lavishly decorated and host an elaborate feast, where he dined alongside all the paris and and his companions, each allocated a seat at the communal table. This practice, symbolising equality, sought to effectively dismantle prevalent social hierarchies. Thus, the Parikhana was an institution built on the principles of gender empowerment, egalitarianism and merit-based progress.

Despite its artistic grandeur, the Parikhana was not without controversy. British observers and colonial administrators often misunderstood and misrepresented the Parikahana as an extravagant indulgence, failing to recognise its role as a serious artistic institution, leading to its dissolution after the Annexation of Awadh in 1856.

Despite the political upheavals that led to its decline, the legacy of the Parikhana endures in the classical arts of India today. Kathak dancers continue to practice the innovations introduced by Wajid Ali Shah, while thumri remains an essential part of Hindustani classical music. Additionally, the aesthetic sensibility that was cultivated in the Parikhana continues to inspire literature, cinema, and performing arts in modern India.

Recent years have seen concerted efforts to reclaim and honour Wajid Ali Shah’s contributions to the arts. Cultural historians and artists have revisited his legacy, staging performances of rahas and exploring his poetry. The ongoing revival of traditional Lucknawi culture owes much to his artistic vision and the influence of the Parikhana.

Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, 1938. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

In the aftermath of the first war of independence in 1857, British forces destroyed large parts of Qaiserbagh, including the Parikhana. Later in 1926 an institute, formerly known as Marris College of Music, was established by the renowned musicologist Pandit Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande, now known as Bhatkhande Sanskriti Vishwavidyalaya. While an existing public notice board identifies the Bhatkhande building as the site of the original Parikhana, this remains historically uncertain, as the current structure clearly dates from a later period.

In line with the convention followed in recently published research works on Awadh, this article uses the italicized Parikhana to denote the intangible concept, while the non-italicized Parikhana refers to the physical space.

Bibliography

Abbas, Saiyed Anwer. Lost Monuments of Lucknow. New Delhi: Nandy Enterprises, 2021.

Llewellyn-Jones, Rosie. The Last King in India: Wajid Ali Shah. London: Hurst and Company, 2014.

Mithal, Sonal, and Paul, Arul. A Queer Reading of Nawabi Architecture and the Colonial Archive: Lucknow Queerscapes. 1st ed. London: Routledge, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003370635.

Oldenburg, V. T. The Making of Colonial Lucknow, 1856-1877. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Shah, Wajid Ali. Parikhana. 1848–49. Translated by Shakil Siddiqui. New Delhi: Rajpal, 2017. [In Hindi].

Skiba, K. “Cultural Geography of Kathak Dance: Streams of Tradition and Global Flows.” Cracow Indological Studies 18 (2016): 55–89.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).