In most historical cities, heritage is tied to grand buildings, where walls, halls and minarets silently narrate tales of the past. However, Lucknow stands an exception. Here, history is not merely confined to architectural marvels but continues to thrive in everyday life, carried forward through one of its most distinctive cultural elements—its zubaan/zabaan (tongue). This zabaan has two significant connotations: one refers to the city’s celebrated cuisine, while the other signifies its refined language. Together, they make Lucknow not just a place of the past but a city that continues its legacy through its traditions. This essay explores the latter.

The Melody of Lucknowi Speech

If food is the heart of Lucknow, its language is its soul. Although Urdu and Hindustani are spoken across Delhi, Agra, Hyderabad and other parts of India, what sets Lucknowi Urdu apart is its vocabulary and lahja (intonation). The city’s dialect is a harmonious blend of Persian and Awadhi, resulting speech that is both elegant and endearing.

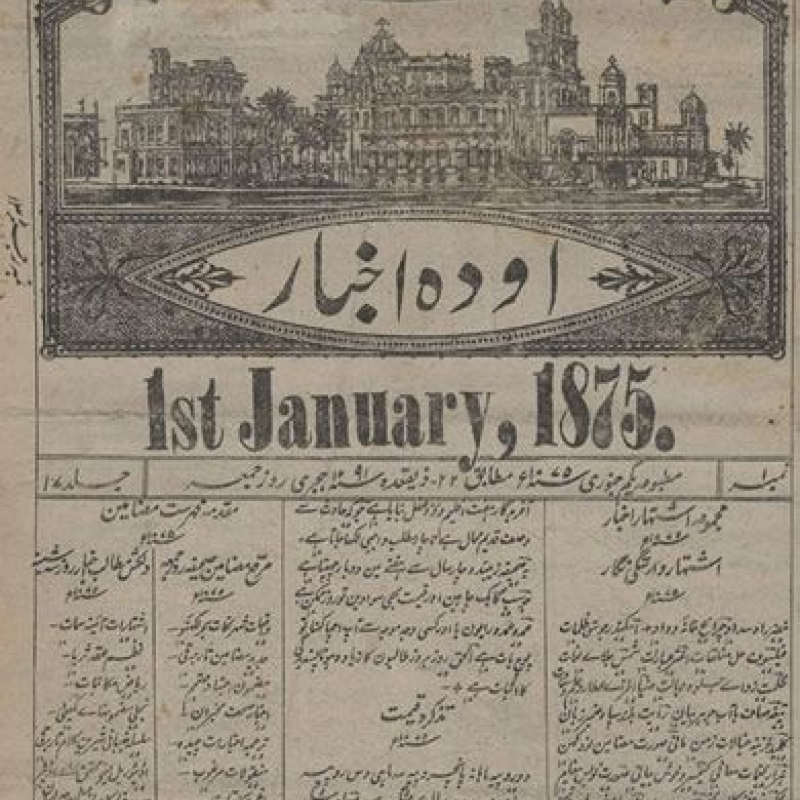

Avadh Akhbar captures the elegance of Lucknow’s zubaan, 1st January, 1875. (Picture Credits: British Library/GetArchive.)

Portrait of Mir Taqi Mir. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Mir Babar Ali Anees. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

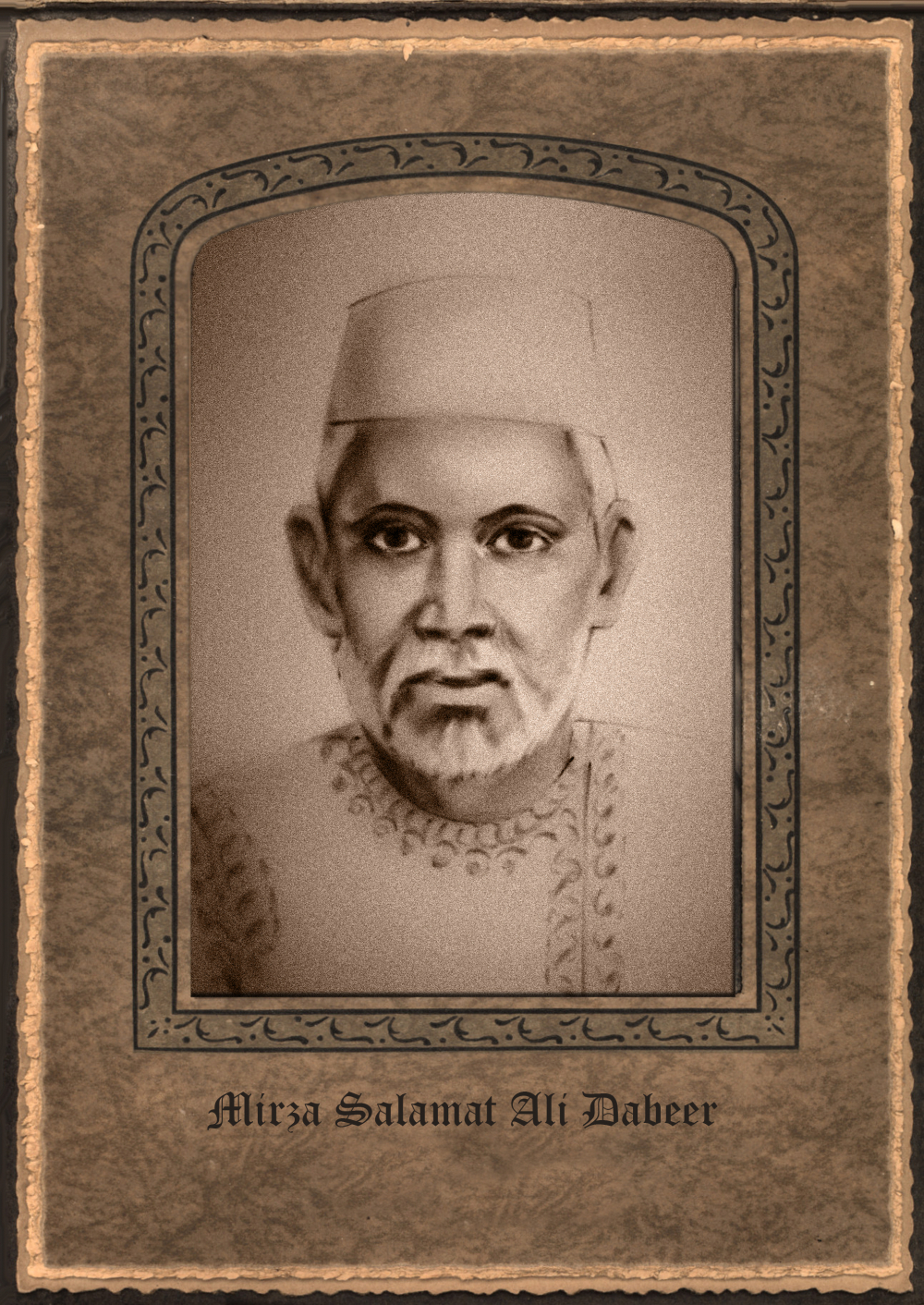

Mirza Salamat Ali Dabeer. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

During the eighteenth century, as Delhi’s political and cultural influence declined, Lucknow rose as a centre of poetry, literature and fine arts. Poets, wordsmiths and artists flocked to the city, enriching its cultural fabric. Among them was Mir Taqi Mir, who, disillusioned by Delhi’s fall, found refuge in Lucknow. Alongside local literary giants like Meer Anis and Mirza Dabeer, he contributed to the linguistic refinement of the city, making Lucknow a hub of literary excellence.

The language of Lucknow has multiple layers, each reflective of different social groups and historical influences. From the polished Persianized Urdu of the Nawabs to the dialects spoken in the streets and homes, Lucknow’s linguistic landscape is diverse and fascinating.

The Many Shades of Lucknowi Speech

Lucknowi zabaan is not uniform but varies across different social and cultural strata. Some of its key linguistic variations include:

-

Begamati Zabaan – The language of noblewomen, spoken in the zenana (women’s quarters) of royal and aristocratic households, as well as by maids and house helps. Known for its overly effeminate tone and poetic expressions, it is rich in idioms and proverbs.

-

Taksali Zabaan – The dialect spoken in specific localities of Lucknow, rooted in the historical taksal (mint) established during Sher Shah Suri’s time.

-

Rekhti – A poetic form of Urdu used to express female voices and perspectives.

-

Awadhi (Oudhi) – The local dialect, spoken primarily by the common folk and often intertwined with Urdu in daily conversations.

The Language of Grace and Wit

Contrary to popular belief, Begamati zabaan was not exclusive to the begums of royal palaces but was spoken in noble and middle-class households alike. Characterised by its lyrical quality and intricate idioms, it was a dialect in which the most mundane matters found poetic expression.

Some fascinating expressions from Begamati zabaan include:

-

Aye wui! – An exclamation of astonishment, often accompanied by a hand gesture (palm on the chin, fingers curled inwards).

-

Aye hai! – Used in moments of distress or disbelief, much like ‘Oh my God!’

-

Nigora – A term of endearment or pity, meaning ‘poor fellow’.

-

Panyachey bhari hona – Refers to someone arriving late or acting overly important, derived from royal women whose heavy embroidered skirts required attendants to help them rise.

-

Bagharna – Describes the bumpy journey on uneven paths, likened to jamuns being stirred in a mud pot.

-

Barasna – While commonly meaning ‘to rain’, in this dialect, it is also a compliment, suggesting something suits a person perfectly.

Street Lingo

Lucknow’s Taksali zabaan emerged from the city’s mint district and is known for its playful distortions of words, reflecting both linguistic creativity and a subtle arrogance unique to Lucknowis. Some common examples include:

-

Darwazza instead of darwaza (door)

-

Idharwal for iss taraf (this side), udharwal for uss taraf (that side)

-

Rashka for rikshaw (rickshaw)

-

Minisiblty for municipality

-

Filam for film

-

Ilam for ilm (knowledge)

Additionally, Lucknowis often use plural forms for singular nouns:

-

Chanwal instead of chawal (rice)

-

MircheN for mirch (chili)

-

Kapde (clothes) even when referring to a single garment

This unique pluralisation likely has roots in Awadhi influences and is commonly heard in both urban and rural settings.

Theatrical Charm

Lucknow’s language has an inherent dramatism, making spoken words feel like a performance. Traditional storytelling forms like Dastaan-goi (Persian-originated oral storytelling) and Qissa-goi (storytelling infused with poetry and prose) captivated audiences for centuries, proving that in Lucknow, a story is not just heard or read—it is performed.

The melodious blend of Persian and Awadhi further enhances the sweetness of Lucknowi Urdu. Phonetic expressions like dhadaam se gir pade (fell with a loud thud) or hawa sana san chal rahi hai (the wind is blowing swiftly) add musicality to speech, making even everyday conversations poetic.

Javed Akhtar, a poet from the Lucknow school of thought, masterfully used such rhythmic expressions in Bollywood lyrics, for example, the song ‘Chale jaise hawaein sanan sanan...’ from the film Main Hoon Na.

The Ever-Evolving Street Slang of Lucknow

Like any living language, Lucknow’s colloquial speech is constantly evolving. Some colourful slang terms include:

-

Bankey – Ruffian

-

Shagirad – Disciple

-

Rangbaaz – Flamboyant person

-

Uthaigeerey – Thieves

-

Late Lateef – Habitual latecomer

-

Lappu Jhanna – Someone weak and frail

-

Paglait – One who acts insanely

-

Bhaukal – Someone with an exaggerated sense of self-importance

In Lucknow, one does not merely speak—one performs, charms and captivates. Whether in its poetic idioms, its elegant intonation or its playful street slang, the city’s language continues to thrive, carrying forward the legacy of Nawabs, begums, poets and storytellers.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).