Awadh’s grandeur was never just confined to its capital cities. It spilled onto its historic qasbahs—semi-urban centres that thrived under aristocratic patronage—each reflecting the status, opulence and mehmaan-nawazi (hospitality) of its rulers. These townships, granted as jagirs to noble families, became epicentres of literature, architecture, cuisine and music, where the echoes of mushairas (poetic symposium), the aroma of slow-cooked delicacies and the craftsmanship of artisans still linger in the air.

A Glimpse of Awadh’s Qasbahs

The princely estates of Mahmudabad, Balrampur, Nanpara, Mankapur, Kotwara, Oel, Salempur and Khajurgaon stand as living testaments to Awadh’s heritage.

Kotwara Palace in Gola Gokarnath, Lakhimpur Kheri, under the stewardship of Raja Muzaffar Ali, stands as a testament to Awadhi heritage. I vividly remember visiting Kotwara Palace in February 2016. Invited by Mr Muzaffar Ali, a filmmaker, designer and cultural revivalist, I joined him on a trip to his ancestral estate, a four-hour drive from Lucknow with a brief stop at the Oel Retreat. By sundown, we turned onto a secluded road flanked by dense teak and sal trees. After what felt like an endless stretch, the fort’s towering walls and chessboard-like watchtowers emerged. The palace complex, with its sprawling havelis and kothis, features grand archways, courtyards and a mehmaan khana (guesthouse) adorned with antique furniture, chandeliers and vintage portraits, reflecting the opulence of Awadh’s nobility.

Kotwara House, Qaiserbagh. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

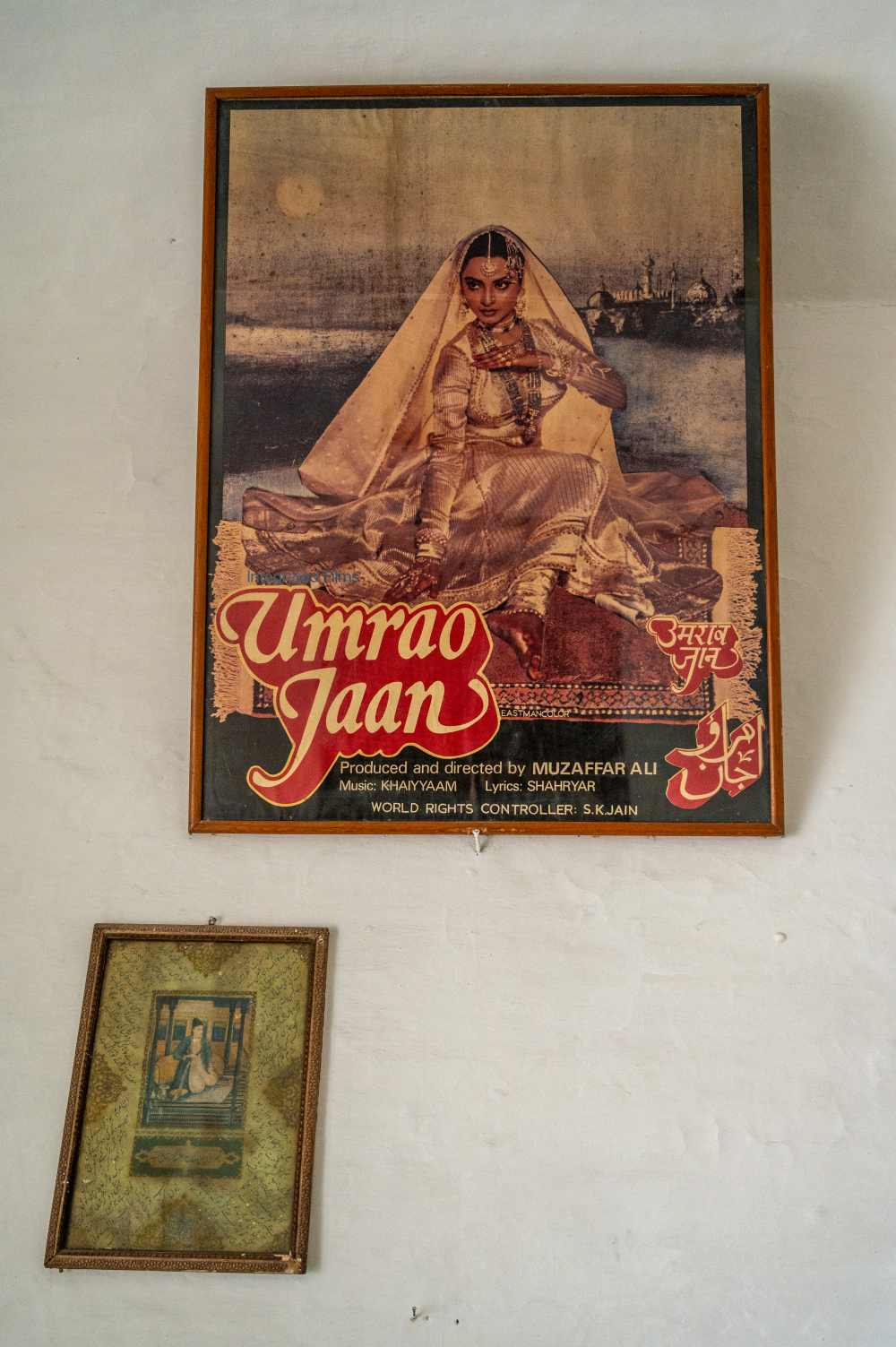

Posters of the movies by Raja Muzaffar Ali on display at Kotwara House—a glimpse into his cinematic journey. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Kotwara House houses workshops of chikankari and zardozi. (Picture Credits: Monis Khan)

Mehmoodabad Palace. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

In Lucknow, Kotwara House near Qaiserbagh chauraha (crossroads) serves as both a heritage home and a living museum. Reminiscent of Pondicherry’s French colonial homes, it houses vintage cameras, film posters, antique furniture and a horse-drawn buggy. It is also a thriving craft centre, where artisans create exquisite zardozi, mukaish and chikankari embroidery for the ‘House of Kotwara’, ensuring the continued legacy of Awadh’s artistic traditions.

Mahmudabad, a historic qasbah of Awadh, embodies the region’s rich cultural, religious and architectural heritage. Located 55 kilometres from Lucknow, the estate, under Raja Mohammad Amir Khan’s stewardship, continues to uphold its Nawabi legacy. At its heart stands the grand Mahmudabad Palace, boasting arched gateways, intricate woodwork and sprawling courtyards. The estate remains a vibrant centre for majlis ceremonies, where recitations of marsiyas and nohas preserve Awadh’s oral traditions and elegiac poetry. The Mahmudabad Imambara and Karbala serve as focal points for Shia rituals. The estate also houses a vast library with rare manuscripts on history, theology and Awadhi culture, ensuring the preservation of its intellectual and spiritual heritage.

Not far from Mahmudabad, Malihabad stands as a culturally significant qasbah, renowned for its world-famous Dussehri mangoes and literary heritage. It was home to Josh Malihabadi, the celebrated Urdu poet known as Shair-e-Inquilab (Poet of Revolution). His ancestral kothi, though not officially recognised as a heritage site, remains a literary landmark. The town’s aristocratic past is also reflected in Raja Sahib’s kothi, though its current accessibility is uncertain.

Sacred Landscapes

Awadh’s spiritual landscape is deeply embedded in its Sufi heritage. In Barabanki, Dewa Sharif, the shrine of Haji Waris Ali Shah, is a beacon of unity, drawing devotees from all backgrounds. The annual Dewa Mela—a blend of qawwali, spiritual gatherings and fairs—celebrates this enduring harmony. Uniquely, Dewa Sharif also hosts a Holi celebration, where colours and Sufi traditions merge in a vibrant display of communal amity. Not far away, Masauli is home to the shrines of Shah Abdur Razzaq Bansvi and Syed Makhdoom Ashraf Jahangir Simnani in Kichaucha, both attracting thousands during urs festivals.

Dewa Sharif in Barabanki. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Besides the Sufi circuit, ahead of Malihabad, Hardoi, steeped in mythological significance, is linked to Hiranyakashipu, the demon king of Hindu lore. Nearby, Naimisharanya is a revered site where sages are believed to have composed sacred texts, including the Vedas. Here, pilgrims partake in simple satvik meals—kuttu puris and aloo ki sabzi—served near the temples.

To the west, Farrukhabad serves as the gateway to Sankisa, a major Buddhist site where Lord Buddha is believed to have descended from Tushita heaven after preaching to his mother. The site, marked by an Ashokan pillar and an ancient temple, is a significant stop on the Buddhist circuit. Further along, Kannauj, once the capital of Emperor Harsha’s empire, is now India’s ittar (perfume) capital. Its centuries-old ittar industry continues to flourish, extracting fragrances from flowers, herbs and even the earth itself (mitti ittar). Kannauj’s Perfume Park and traditional distilleries offer glimpses into its rich history and craftsmanship.

Artisanal Traditions

Awadh’s qasbahs are not just relics of the past; they are thriving hubs of craftsmanship. Farrukhabad remains a centre for intricate zardozi embroidery, once patronised by the Nawabs. Khairabad is famed for its handwoven carpets and durries, while Sultanpur specialises in moonj (grass) weaving, producing eco-friendly baskets through traditional techniques. Hardoi and Barabanki have upheld their legacy in handloom weaving and textile printing.

Camel skin ittar bottle from Kannauj. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Kakori, synonymous with its legendary kebabs, is also known for its delicate wooden inlay work, where artisans craft intricate designs with remarkable precision. The town is deeply tied to India’s freedom struggle, with the Kakori Memorial honouring revolutionaries like Ram Prasad Bismil and Ashfaq Ullah Khan. Nearby, Mohaan preserves the legacy of Hasrat Mohani, the poet and freedom fighter who coined the slogan ‘Inquilab Zindabad’.

Qasbahs like Kakori, Mohaan and Malihabad remain vital centres for chikankari embroidery, from where artisans supply their work to Lucknow’s historic Chowk area. Meanwhile, Malihabad’s renowned mango orchards continue to yield exquisite varieties, with families preserving age-old recipes of aam panna, pickles and chutneys.

Natural Heritage

Beyond their rich history and craftsmanship, these qasbahs provide a gateway to Awadh’s captivating natural landscapes. Dudhwa National Park, near Lakhimpur Kheri, shelters Bengal tigers, swamp deer and the elusive one-horned rhinoceros. Pilibhit Tiger Reserve, nestled along the Indo-Nepal border, offers an immersive experience amidst dense sal forests and diverse wildlife. For bird watchers, Nawabganj Bird Sanctuary (now Shahid Chandra Shekhar Azad Bird Sanctuary) in Unnao attracts migratory birds like Siberian cranes and painted storks. Seasonal wetlands in Hardoi and Sandila offer additional birdwatching opportunities, while the Gomti River winds through these historic towns, providing scenic landscapes and glimpses of traditional riverine life.

Dudhwa National Park. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Nawabganj Bird Sanctuary. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Culinary Remains

Awadhi cuisine is far more elaborate than just the celebrated non-vegetarian fare. Breads from various millets, the use of seasonal vegetables such as sarson (mustard) and methi (fenugreek), and porridges including sweet potato kheer or rasawal—a dessert made from sugarcane juice and rice—reflect the diversity of its culinary traditions. The mango season brings a variety of delicacies, from mango kheer and aam panna to pickles and a special Awadhi mango chutney called navratan chutney or galka. Also noteworthy are the mango orchards of Malihabad and Barabanki, fresh jaggery from the sugarcane belt of Sitapur, Lakhimpur, and Bahraich. Beyond Malihabad, Sandila is known for its famed Sandila peda, a sweet delicacy perfected over generations.

Awadh’s qasbahs are not just about nostalgia; they are living, breathing spaces where heritage is not only preserved but practised. They offer an invitation—to step beyond the grand facades of Lucknow and Faizabad and into the heart of a culture where history, hospitality and craftsmanship endure. For those who venture into these forgotten townships, the past is never too far away—it lingers in the air, in the flavours and in the echoes of poetry, waiting to be rediscovered.

This essay has been created as part of Sahapedia's My City My Heritage project, supported by the InterGlobe Foundation (IGF).