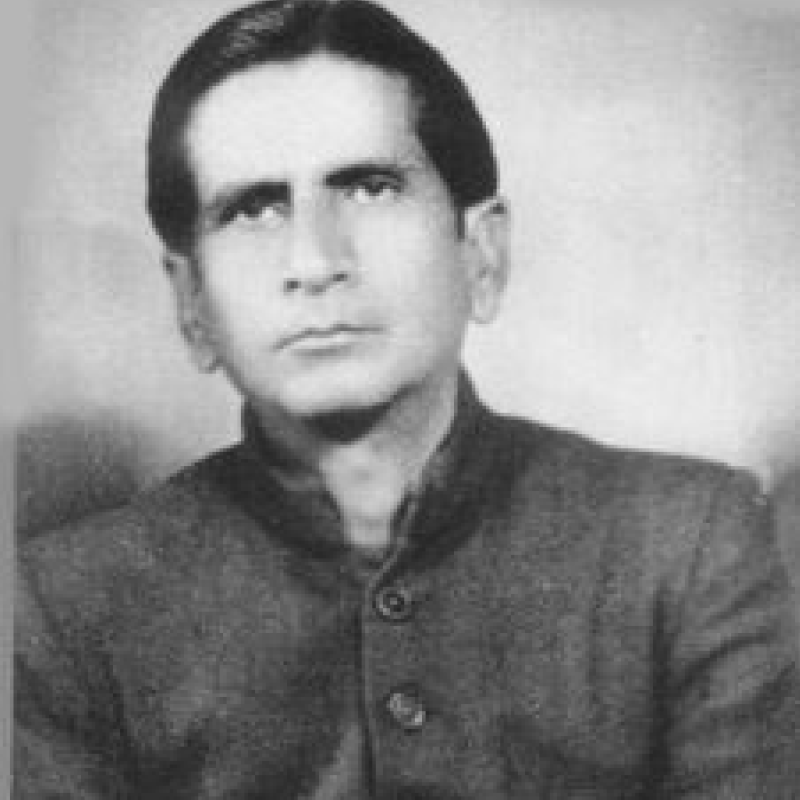

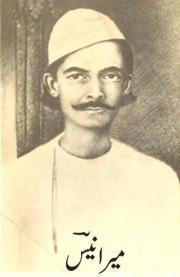

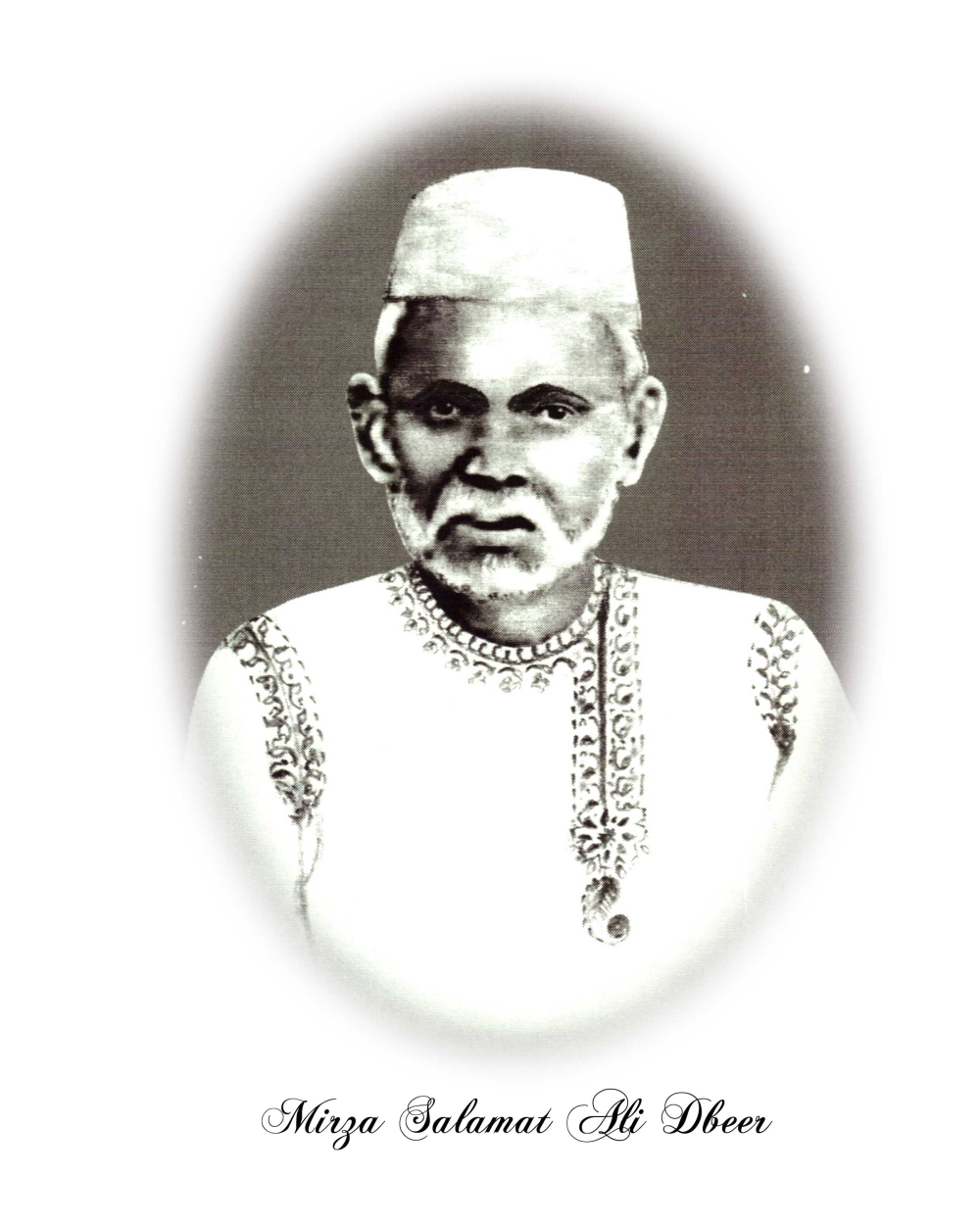

To speak of Lucknow is to invoke a world of exquisite tehzeeb (etiquette), refined speech and fine poetry. Here, poetry does not belong solely to the poet; it permeates the air of the chowks, flows with the scent of keora in the kothas (courtesan houses), and echoes through the corridors of once-glorious mansions. From the ghazals of Mir Taqi Mir and the rekhtis of Allah Khan and Rangin to the marsiyas (elegiac verses) of Mir Babar Ali Anis and Mirza Salamat Ali Dabeer, and the nazms (verse) of Josh Malihabadi, Lucknow’s centuries-old literary tradition is a palimpsest of emotions, weaving together tales of love, loss, rebellion and nostalgia.

Here, poetry was not merely an artistic pursuit; it was a way of life. The mushairas (poetic symposiums) that flourished in the city were not just performances but communal celebrations of linguistic richness and intellectual engagement.

Dilli’s loss Lucknau’s gain

The waning fortunes of the Mughal Empire in Delhi in the mid-eighteenth century left its poets in financial ruin. Deprived of royal patronage, many migrated to the prosperous courts in Hyderabad, Murshidabad and, particularly, Awadh, which despite maintaining their status as Mughal vassals, had gained considerable autonomy and wealth. Poets such as Sauda, Mir Taqi Mir and Ghulam Hamdani Musahfi, who formerly graced the imperial courts of Delhi, found new patronage in Lucknow, where the Nawabs, eager to enhance their cultural stature, lavished generous stipends upon them. Sauda, initially hesitant, eventually accepted Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula’s invitation and was granted the title Malik-ush-Shu’ara (Poet Laureate). Mir Taqi Mir, disillusioned by Delhi’s decline, reached Lucknow in 1782 and secured employment under Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula.

Portrait of Mir Taqi Mir. Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons.

Mir Babar Ali Anees. Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Mirza Salamat Ali Dabeer. Picture Credits: Khabir Hasan/Wikimedia Commons.

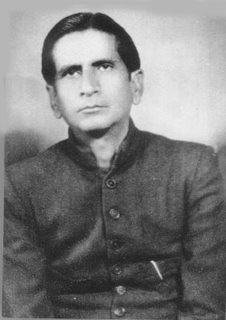

Josh Malihabadi. Picture Credits: Photo Division, GOI/Wikimedia Commons.

Painting of Mirza Muhammad Rafi Sauda by an anonymous painter of the Mughal Empire. Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons.

An engraved portrait of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (r. 1847-1856), 1872. (Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

Despite the initial dominance of Delhi’s literary émigrés, Lucknow produced its own poetic stalwarts too. Imam Bakhsh Nasikh, a native of Faizabad, laid the foundation of the Lucknow School of Poetry, characterised by linguistic opulence, complex metaphors and a heightened focus on aestheticism. His rival, Khwaja Haidar Ali Atish, brought an unpretentious, soulful depth to Urdu ghazals. Subsequently, Mirza Dabeer and Mir Anis emerged as two towering marsiya poets. Their dramatic recitations, full of vivid imagery and emotional intensity, showcased the power of the musaddas (a form of poetry spanning over six lines). Beyond the grandeur of the deeply evocative marsiyas that mourned the tragedy of Karbala, the city became synonymous with the shahr-ashob (poems of lament for urban decay), qasidas (panegyric odes) and masnawis (narrative poems).

Contrary to colonial narratives, many Nawabs were avid patrons of literature. Asaf-ud-Daula was a poet and Meer Soz’s disciple. Wajid Ali Shah, writing under the pseudonym ‘Qaisar’ and ‘Akhtarpiya’, composed ghazals, marsiyas and masnawis, his verse steeped in longing:

Meri chashm-e-ibarat ne dekha yeh manzar,

Jahan bhi nazar daali, tumhi tum nazar aaye.

My eyes beheld this wondrous sight,

wherever I looked, I saw only you.

Ghazal’s Embrace and Courtesan’s Influence

If the marsiya lent grandeur to public mourning, the ghazal was the heartbeat of intimate gatherings. In the interiors of Lucknow’s kothas, poetry found an unspoken ally in music and dance. The tawaifs, guardians of classical arts, were more than mere performers; they were patrons and preservers of poetic traditions. These women, simultaneously celebrated and ostracised by society, held the power to make or break a poet’s reputation. Their mehfils were where poetry was refined and perfected; it was said that a poet’s success was often determined by the praise of the tawaifs, their discerning ears and artistic sensibilities shaping the course of literary taste. The courtesans dictated poetic fashion—an impromptu couplet from their lips could elevate a poet’s stature, just as a dismissed verse could consign one to obscurity. In these dimly lit chambers, adorned with chandeliers and silken drapes, poetry found a home beyond the courts. The voices of poets like Jur’at, Insha Allah Khan Insha, Jafar Zatalli, Rangin and Aatish Lakhnawi, with their playful yet profound verses, were carried by the melodies of the tawaifs, turning poetry into song, and song into a timeless memory.

Khwaja Haider Ali Aatish. Picture Credits: Wikimedia Commons.

Decline, Revival and the Legacy

Like all cultural efflorescence, the poetic grandeur of Lucknow saw a decline with the political upheavals of during the British annexation of Awadh in 1856 and the subsequent Revolt of 1857. The devastation wrought by the Revolt sparked a new wave of poetic expression in voices like Ameer Minai and Josh Malihabadi, who wove resilience into their couplets.

Photograph of Poet Amir Meenai, c. 1890. Picture Credits: Aaminai/Wikimedia Commons.

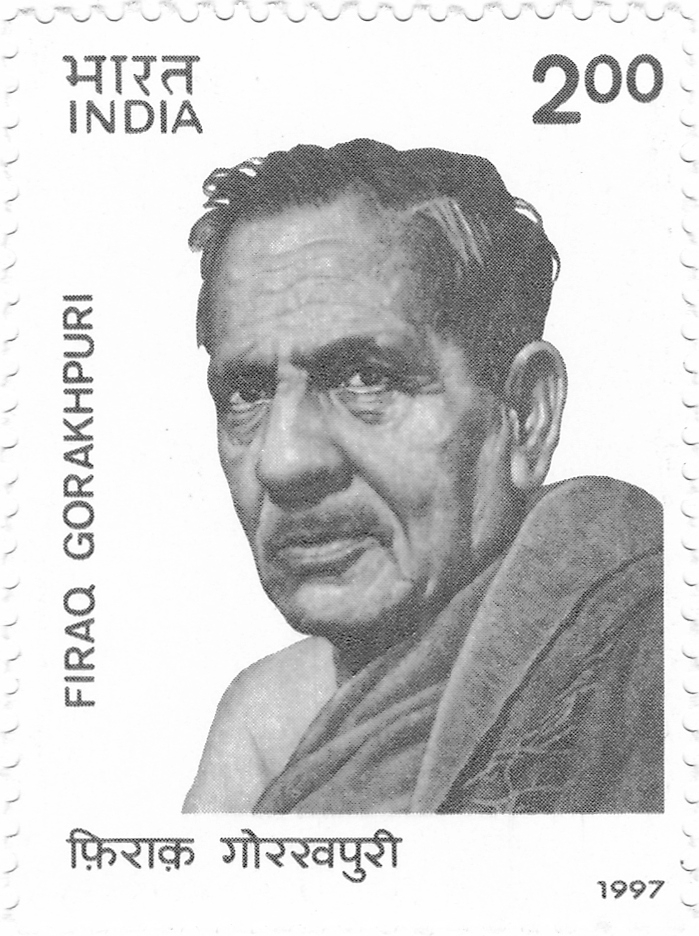

Firaq Gorakhpuri on a stamp. Picture Credits: India Post, GOI/Wikimedia Commons.

Majaz Lakhnawi. Picture Credits: The Lucknow Observer/Wikimedia Commons.

Beyond the mainstream literary culture, Lucknow also harboured underground poetic traditions. Exclusive gatherings in Mohalla Pir Bukhara continued to host readings in secrecy, even after the upheavals of 1857. Similarly, there existed a lesser-known tradition of mushairas dedicated to bawdy and irreverent poetry, recited in elite private circles. Figures such as Sahib Qaran, Jan Sahib and Chirkin were known for composing verses that defied the decorum of conventional literary spaces.

In the twentieth century, the Progressive Writers’ Movement redefined the poetic currents of Lucknow. No longer confined to the realms of aristocratic melancholy, poetry became an instrument of resistance, a call to justice. The verses of Firaq Gorakhpuri and Majaz Lakhnawi pulsed with social consciousness, painting the city in the hues of revolution and romance. Majaz, a poet of intoxicating despair and undying hope, wrote:

Ae Lucknow ki shaam, bata tu ne dekha hai kahin, Ek shaks jo har raah pe rukta hi chala jaaye?

O evening of Lucknow, tell me, have you ever seen a man who pauses at every path, yet keeps moving on?

Today, Lucknow’s poetry is no longer confined to the courts or kothas, but continues to evolve, finding expression in contemporary platforms. Lyricists such as Shakeel Badayuni, Kaifi Azmi and Javed Akhtar have carried forward the tradition of Urdu poetry, infusing it into film lyrics that resonate with millions. Songs like ‘Chaudhvin ka Chand ho’ (Shakeel Badayuni) and ‘Tum itna jo muskura rahe ho’ (Kaifi Azmi) embody the delicate poetic sensibilities that originated in the poetic circles of Lucknow.

Even today, the city breathes in couplets—whether in tea stalls where young poets recite verses, in literary festivals where new voices emerge or in the cinematic verses that reach a global audience. In this, Lucknow remains not just a city but a living poem, eternally unfolding, waiting to be recited.

Bibliography

Oldenburg, V. T. The Making of Colonial Lucknow, 1856-1877. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Russell, R., and K. Islam. Three Mughal Poets: Mir, Sauda, Mir Hasan. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968.

Hamid, Syed Ali. ‘Lucknow: Literature and Culture.’ Academia.edu, accessed 9 April 2025, https://www.academia.edu/99637810/Lucknow_Literature_and_Culture.

‘A City of Poets: Lucknow and Its ‘Shayars’ (Column: Bookends).’ Business Standard, 8 February 2015, accessed 9 April 2025, https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ians/a-city-of-poets-lucknow-and-its-shayars-column-bookends-115020800047_1.html.