Sindh: The land of my ancestors

I am a fourth-generation Bhaiband. In our community, the men work in trading companies, living overseas. In the old days, the families lived at home in Hyderabad, Sindh. At the end of every period of two or three years, called the musafri or ‘trip’, the men would return home for a break. My father, my grandfather and my great-grandfather spent their entire working lives in the Dutch East Indies, as Indonesia was called until 1945. As per the tradition of our community, they visited their families in Sindh for two or three months every two or three years. My father, Boolchand, was one of the earliest Bhaibands to take his wife, Muli, to live with him, which he did in 1930. He could only do this because he was working with his father and not one of the large Bhaiband firms where he would not have been permitted to.

My elder sister Mohini and elder brother Jiwat were born in Kotaraja, located near the northern tip of Sumatra, where the family had a small store. The third child, Haresh, was born when they were on holiday with the family in Hyderabad. Kotaraja is a port which in those days depended largely on regular sea traffic stopping there to replenish coal. But new technology meant that ships could travel longer distances without refuelling, and fewer ships were stopping at Kotaraja. Business in Kotaraja was declining, and my father decided to move. In 1939, my father took over a store in Langsa, a prosperous plantation area further south along the coast, and the family moved to live with him in an apartment above the store.

Four more daughters were born to my parents in Langsa. These were the years of the Second World War. Sea routes were closed to civilians, communication dwindled and my parents were isolated from their loved ones at home in Sindh. It was a time of uncertainty and fear which my mother never forgot. Soon the Japanese landed with an eye on the oil fields. Europeans in the area were rounded up and put in concentration camps. My mother was an asthma patient and when my father’s name was seen in her Dutch doctor’s diary, my father was incarcerated too. His stepbrother Lachmandas in Medan came to Langsa and was able to convince the Japanese authorities that we were a family of traders from India and had nothing to do with their war, and my father was released.

As soon as the war ended, my parents arranged to travel home. They had made a big decision: to return to the traditional Bhaiband life. My father would continue with his business in Langsa and come to Hyderabad every few years to see his family. My mother came from a wealthy family; her father had made his fortune in Durban. She believed that she would live comfortably in Hyderabad. Life, however, had its own plans.

Beautiful Muli, in her parents’ home in Hyderabad

After some months enjoying life at home, my father went back to Langsa. My elder siblings started school, where they had to learn to speak, read and write their mother tongue Sindhi. I was born on July 8, 1946 and remember nothing of Hyderabad, the place where I spent the first year of my life. I remember nothing of the urgency and fear in which my mother carried me and, herding her children together, arrived at the Hyderabad railway station with her mother and other female relatives with their children. Ours was only one of many such families at the Hyderabad railway station, anxious and eager to leave the city as soon as possible to escape the riots following the Partition of India in August 1947. The Bhaiband men were working in other countries. The women were now leaving their homes in Sindh for the last time in the midst of lawlessness and fear, with their children and the elderly.

My father was away and my mother fled along with other women of the family, travelling in overcrowded trains like this one.

Our train crossed the new border and arrived in Ajmer. We were allotted one room in a camp overflowing with refugees like us. Everyone was looking for a safe place to settle. People talked to each other, asking others where they had come from and where they were going, and seeking suggestions about where they could live and what kind of opportunities were possible to earn money.

My father was in the process of moving from Langsa to Tanjung Pinang, where he had taken a partnership with a Singapore family to run their store. Once he was settled there, he was able to make arrangements for us to join him. Our family was lucky in the sense that we were never really refugees from Pakistan. Most Sindhis had to find a new place and start afresh but for us Bhaibands there was already a base. Our family had a welcoming home in Indonesia and we went to live there.

Indonesia: My childhood home

Tanjung Pinang is a small island off Singapore with a population of about 12,000 people. We lived just a few hundred metres from the sea, and I spent a lot of time running around and swimming in the sea with my friends. In those days, my siblings and I spoke Indonesian to each other, and I think to our parents too. Actually, I don’t remember speaking to my father at all. He was a traditional father, who didn’t talk much to his children. So there was no sitting down and doing the homework and things like that. My mother also did not have the time to sit and talk with us. I was her eighth child and three more were born after me. With so many to take care of, she was busy all the time. We ate Sindhi food but my mother exchanged recipes with our neighbours and had become an expert at Indonesian cooking too. And we children loved the Indonesian street food.

In Tanjung Pinang, which was actually just a little village, my father ran a store for the Binwani family who were based in Singapore. He had one employee, KG Samtani, who lived in our home and was always treated like our elder brother. It was a shop that sold clothing, toys and other things. There were eleven of us children, but my father never let us have anything from the shop. We all knew, from the youngest age, that our father was an honest, principled man, very conscious of the fact that he was working for somebody. We lived above the shop and it was quite a big place, with a big patio at the back, but there were not many rooms, and there was not much privacy.

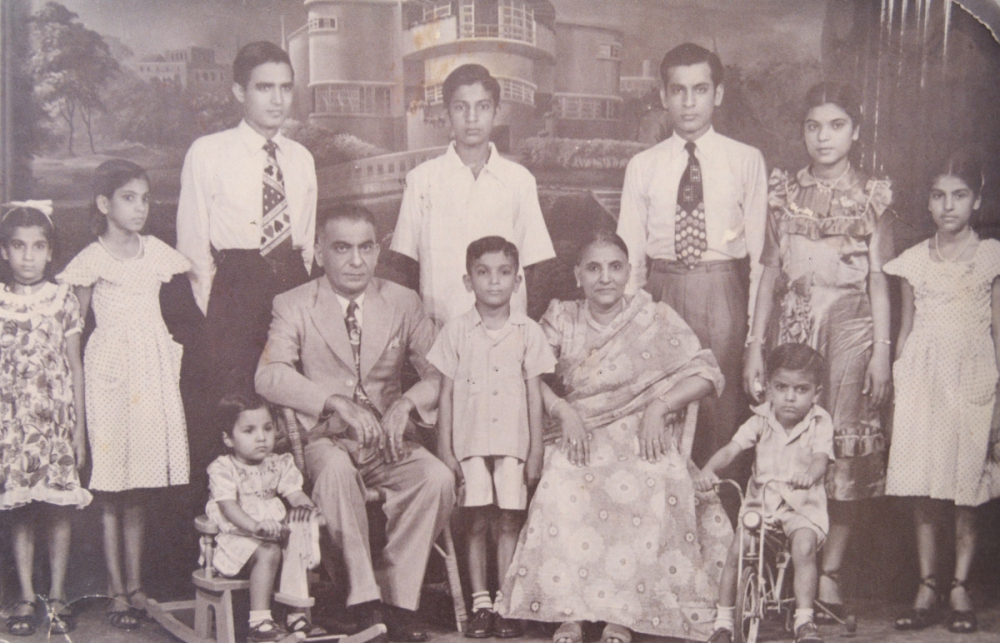

A family photo taken in a Tanjung Pinang studio. My eldest sister, Mohini, was already married and Ishu not yet born. Sheila, Chandra, Babe, KG, Boolchand (my father), Hassomal, Tulsi, Muli (my mother), Jiwat, Ramesh, Lacha, Pushpa. All the children’s clothes seen in this photo were sewn by their sister Mohini.

When I was 11 and my youngest sister Ishu was one, I was sent away from home and my carefree Huckleberry Finn life came to an abrupt end. My parents sent me and three of my elder sisters, Lacha, Chandra and Pushpa, to Medan, a town on the coast of Sumatra, where my grandmother lived with her three sons and their families. Medan had English-medium schools, and our parents wanted us to have our education in English. My uncles ran a shop called Toko Boolchand at Number 40, Surabaya Road. My grandfather had opened it before the Second World War started, and it had my father’s name.

My grandmother, my father’s stepmother, was a very disciplined person. She strongly believed that an idle mind is the devil’s workshop and she kept my sisters busy with stitching, embroidery, cleaning, washing and cooking. I was not kept busy, but I was not encouraged to go out of the house either. We came home from school, had lunch and would sit down to read or study.

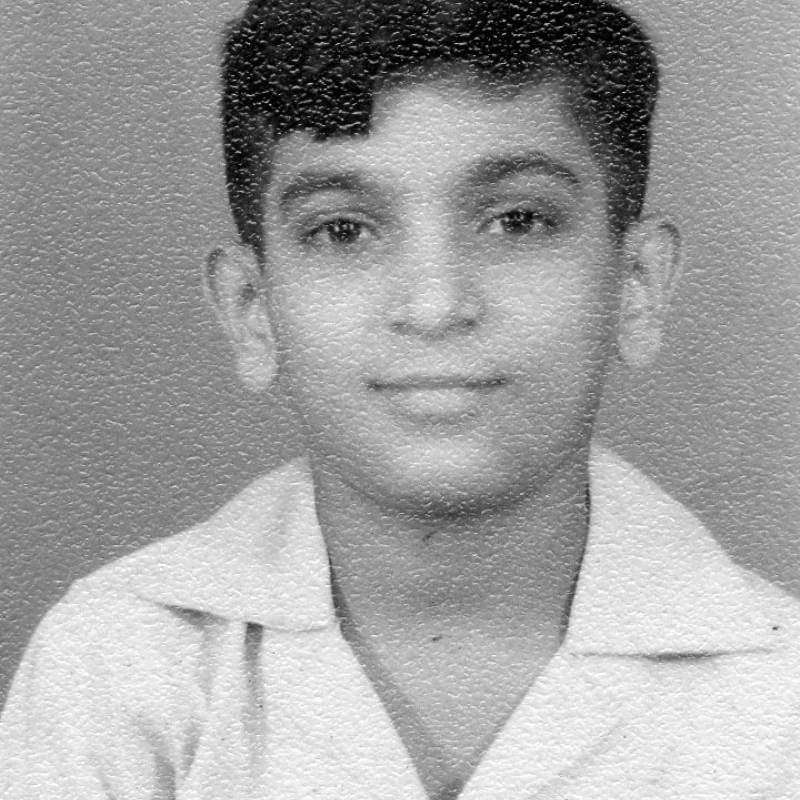

Standing (L to R): My cousin Kamla, my sisters Pushpa and Chandra, our grandmother Ammi, sister Lacha, my cousin Murli and Tulsi (me). Seated (L to R): My cousins Vidya, Pushpa, Jani, Prem and Dhoraj

In those days, there was a strong anti-foreigner feeling in Indonesia and the government had decreed that only foreigners could learn English. We were admitted to the Khalsa English School, which had two sections, an Indonesian one for Indonesian nationals, and an English section for foreigners who were mostly Indians and Chinese. There were quite a few Sikhs in Medan. They owned dairy farms and ran dairy businesses, and they supplied us milk. There was a Gurudwara right next to the school.

Though we were a well-established family in Medan and my uncles were well connected socially, we lived a simple life. With so many kids, things could not have been easy. Nowadays we live in abundance. But in those days, people would go to the market every day and just buy the day’s needs. With Ammi’s background of careful spending, she hated waste.

My grandmother was also strict about speaking our own language so though among us children we spoke Indonesian, this is where I picked up my Sindhi. We spoke with our uncles as well in Sindhi but with the aunts we spoke English, because they had all studied in English schools.

About one year after we arrived in Medan, my sisters Lacha and Chandra were sent back to our family in Tanjung Pinang. And then, about two years later, my mother came and visited, bringing little Ishu with her. She stayed for just a few days and went back, and that was the only time I saw her for many years. Unfortunately, for lack of money, we were never sent back to Tanjung Pinang. My mother had come to Medan to see us because our parents had decided to leave Indonesia and she would not see Pushpa and me again until we had completed our education. After some years they had decided that it was time for another fresh start. My parents chose the Indian city of Pune in which to have the new family home.

Leaving Indonesia

In the late 1950s, Indonesian nationalism was rising but the economy was struggling. Sukarno was president, and foreigners were told that they should either move out of Indonesia or become Indonesians. They had to change their name, their lifestyle and their nationality. Luckily they were not told to change their religion.

My uncles never changed their names, but my eldest uncle, Ghanshamdas, who had a very strong entrepreneurial bent, had gone to Hong Kong to look for further business. When my parents and siblings left Tanjung Pinang to settle in Pune, he wrote to my father, asking him to come to Hong Kong and join him in the business as his partner. My father decided to take up the opportunity. Uncle Ghanshamdas also sent for his eldest son Murli to join him. Murli had not completed his schooling, but was well spoken and mature. He joined his father’s business in Hong Kong and quickly became a good salesman.

With his chair turned to face the camera is Mangomal, a Sindhi gentleman who worked with Ghanshamdas. On either side of him are Ghanshamdas and his wife Mohini. A British and a Chinese couple are seen in this photo; the husbands worked with the British firm Guthrie Company. The Sikh gentleman wearing a turban is Meher Singh, the Indian Consul in Medan. Next to him sits Lachmandas, and Kala is across the table, next to Mohini.

With Murli gone, my routine changed because I was expected to take over his duties working at the shop after school. I was fourteen or fifteen and my work life began with errands and accounting vouchers, and later I was on the sales floor for a little while. It was mostly textiles, which in those days’ people bought by the metre and got tailored. It was a boring life but there was one thing which kept me going. A few blocks from our bungalow was the American Consulate and the United States Information Service (USIS) there had a big library which also screened films. They were documentary movies and mostly propaganda—in those days, soon after the Second World War, the Russians were showing their films, the Chinese had their magazines, and the British had their library and magazines. The USIS library showed their documentary movies daily and free of charge, in a small theatre which could seat 30 or 40 people. I would spend a large part of my holidays watching those movies, which soon had their effect on me. The only thing I wanted was to go and live in the United States.

The power supply to Medan was not sufficient for the city, and area-wise brown-outs meant that alternate nights would be dark. During exam time when we woke early to study, we often did so by candle light or under a gas lamp. In fact, there was nothing to do but study. This is why, when I eventually took my school-leaving examination which came from Cambridge in England, of forty-odd pupils, I was one of only two to pass, the other being a Chinese boy.

After this I worked in the shop for about one year, and then was sent back to India with a six-month stopover in Hong Kong. I was put to work with my father and uncle doing odd jobs but I was 18 and must not have contributed much. They were importing from Japan and selling to shops, so we used to visit shopkeepers and showing them samples of the material and sending them what they had selected the next day. There were both Indian and Chinese shopkeepers, but mostly Indians. In Hong Kong, all ten of us stayed in one apartment. We worked from Monday to Saturday and on Sundays there would be family outings. We did not mix much with others.

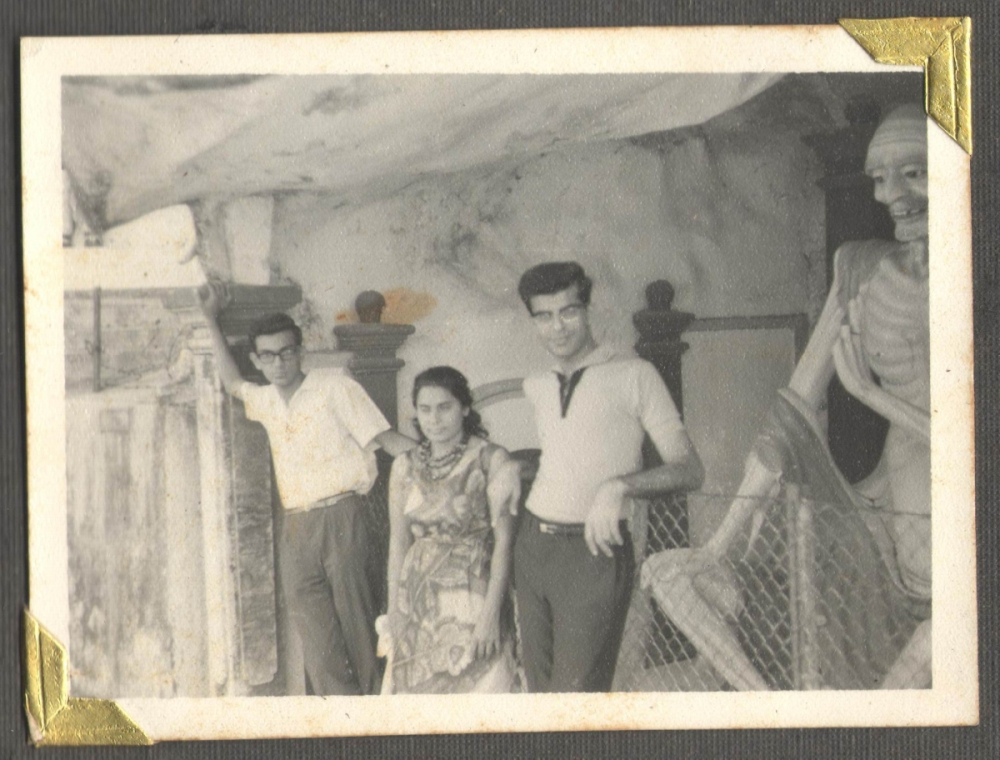

With my cousins Kamla and Murli at Tiger Balm Gardens in Hong Kong

By the time I left for India, a coup had taken place in Indonesia and my uncles had sold the house and closed the business. We were not the only family to leave Indonesia. There were many others like us in Bombay and Pune. It was like returning home, another forced exodus similar to what we faced when Pakistan was created. There was a strong feeling that Indonesia was hostile and India would have better opportunities. People started opening businesses, investing in factories. A lot of them failed. Working in India is quite different from working in Indonesia. But my Uncle Ghanshamdas was a visionary. After opening a business in Hong Kong with my father, he also started doing business in Bombay. When my Uncle Lachmandas reached Bombay, there was already a running business. In Indonesia, we ran a textile company and so understood the textile business well. Therefore, in Hong Kong too they opened a textile shop with mostly shirting, which is cloth to make shirts. They imported from Japan and sold to the local people. In India, where local production was good, they bought from factories, and exported to Sri Lanka, which was known then as Ceylon, where they had family members and good business contacts.

When I landed at Bombay, my elder sister Lacha was there to pick me up and we left by train that evening for Pune. It was the first train ride of my life aboard the Deccan Queen and I was going to be reunited with my family after more than seven years.

Pune: The family home

All through my years away, I had missed my family a lot. When I was finally reunited with them, I felt odd and for the first few weeks even addressed my mother as ‘tavha’ which is the Sindhi word for ‘you’ when you address someone with respect.

It was also my first time in India, but India and Indonesia are quite similar, so I wouldn’t say there was a drastic change or culture shock. It was unhygienic, dirty, dusty, people were very friendly and social, there was no privacy—those basic things were all the same. I was at home with my family for six months and the house was always noisy with people constantly visiting, and although I was quite an introvert and did not participate much, I enjoyed the whole thing as an onlooker.

I had always wanted to go to university and study further. But my family found education beyond matric to be pointless, especially for the boys. Some of the girls in our family did go to college, so that they would be occupied until a right match was found for them.

My mother took her duty to get us married very seriously. Each marriage was a project: finding the match, building a relationship with the new in-laws, carrying out all the traditions and sending off the daughters or welcoming the daughters-in-law. She did all these things with wholehearted enthusiasm. My mother loved to arrange marriages. There were also professional women whose business it was to make matches and they would be paid a fee or a piece of jewellery. In our community, the men were usually working overseas and the families lived in Pune or Bombay, which therefore became big centres for matchmaking.

Many of our relatives living in other places would come and stay with us, bringing their eligible sons or daughters and staying on until the right match had been found and the marriage actually took place. We lived in a two-bedroom apartment with one-and-a-half bathrooms, but it was never too small for our relatives. It sounds impossible but there were times when 40 and 50 stayed there together for a wedding. With so many marriages, we had developed a standard format: the engagement would be held in the temple. The sagri, a ceremony in which the groom’s sisters dress the bride and deck her with flowers and jewellery, was held at home, and the satavaro, the party given by the girl’s side after the wedding, would be held in our small living room with home-cooked food. The wedding itself would be held in Kagazwala Hall, where most of the Bhaiband marriages took place. Whether you were rich or middle class, there was only one wedding hall in Pune. Money was spent on jewellery for the bride and on exchange of gifts, but not for pomp and show. Later, of course, this would change.

Traditional song at a family wedding celebration in our home

After I had been at home for six months, my sister Lacha had a job offer for me with her husband’s relatives in Nigeria, and I left on a three-year Sindhwork contract at a salary of 11 pounds per month for the first three years. After that there would be a break of a few months and then on the second musafri it would be 20 pounds.

Nigeria: A taste of the Sindhworki life

The three years I spent in Nigeria gave me good experience. Here too it was a textile business, importing fabric popular in Africa from Japan and selling locally. I started off in the warehouse, moved to the office doing accounts, then correspondence, and then sales, thus gaining an overall exposure. What I learnt in those three years I wouldn’t have learnt working 30 years in my father’s business. It is a different feeling when you work for someone else. The discipline and responsibility is different. Within the family you can take things for granted. Here I would even take work home.

Ours was a small company, but there was a bigger company linked to this and they had a lot of staff whom we used to mix with. At first I was given accommodation in a staff house with three or four others, all between 18 and 25, unmarried, recently out of school, all from India. We were given training and there was an understanding that we would stay till the end of our careers. In Nigeria, the Bhaiband social life was conducted under a strict code: if you were an employee, you would only mix with other employees. Managers would only mix with other managers and bosses would only mix with other bosses. On Saturdays we worked half-day and would mostly go and watch movies, and on Sundays we went to the swimming pool. It was in Lagos that I had my first beer. Malaria was rampant in Nigeria and there was a belief that when you drink alcohol you don’t get malaria! My best friend then was a young man called Madhu. He worked for a company called Gulabani. I have made many efforts to locate Madhu but have not been able to.

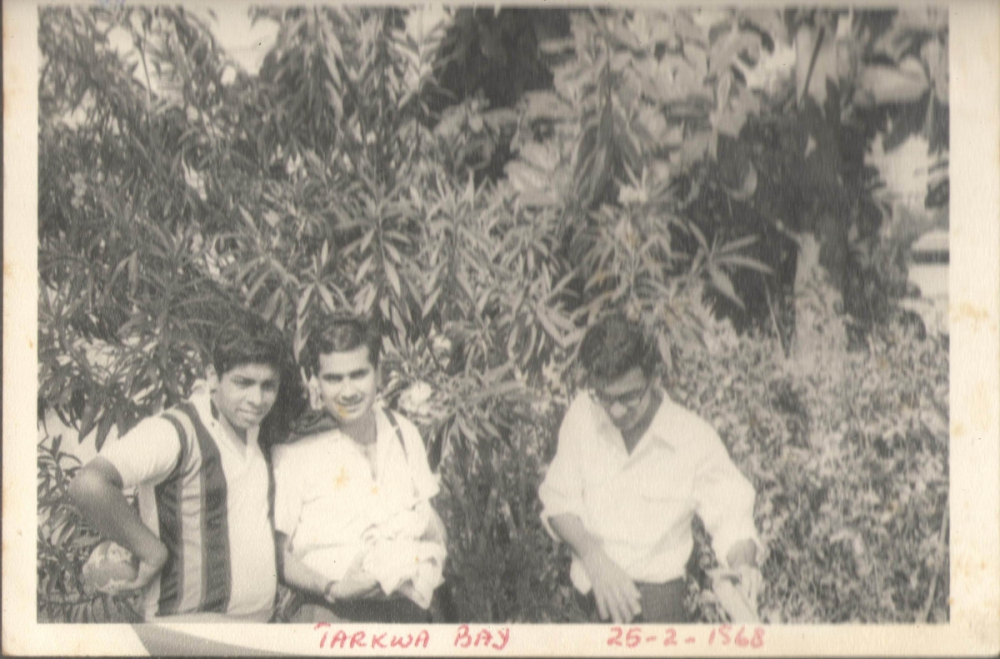

Madhu, Murli Hathiramani and me, enjoying a picnic at Tarkwa Bay. After I left Nigeria, we lost contact and since 2014, I have been trying to locate Madhu with no success

After a year or two business was bad and they downsized. Only two of us were left and the owners moved us to live in a shared room in their bungalow. Coincidentally, the person with whom I worked and shared a room, Ramesh, has a brother called Rajan and it was Rajan’s son Manesh to whom my daughter Priya got married many years later. Among us Sindhworkis, you will always find connections like this.

At the end of the three years, my contract was over. I decided to start my break of six months with a two-week tour of Europe. The first stop from Lagos was always Beirut, so I spent a couple of days there and then went on to London, Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris, Madrid and Rome with a copy of Europe on $10 a day, a staple of our times, in my hand. It was a wonderful experience.

Back at home in Pune, I was seeing my father and mother together for the first time since leaving home at eleven. My two youngest sisters were still in school and one of my brothers was working in Bombay while his wife lived with us in Pune. In the mornings my sisters and I would just sit and look out of the window, watching people pass by. It was a relaxing, enjoyable time. As it came to an end, I started waiting for my boss in Nigeria to call me back. After a few weeks of looking out for a letter with a ticket in it, we started waiting for the postman every morning, calling out to him, 'Is there any letter from Nigeria?' But nothing came.

Hong Kong: Growing a family business

My father had come back home from Hong Kong because his stepbrother had terminated their partnership. He was at a loss about what to do next. With eleven children, some still quite young and some girls for whom he would have to provide dowries, he was quite depressed. He wrote to his brother asking for a better settlement and eventually my Uncle Ghanshamdas replied, offering that if he returned to Hong Kong and opened his own business, he would help by supplying him goods.

So in March 1969, my brother Haresh and I went with our father to Hong Kong to open our own business Mulitex, named after my mother Muli. We rented a store on Stanley Street and put up a partition for our personal belongings and folding aluminium beds. At night we would open up the beds and sleep among the bales of textiles, takias as they are called. In the morning we would fold them back, so that everything was like a shop again. We didn’t have much money, but my uncle was generous enough to give us samples and when we received an order, he supplied us with the goods. We would set out every afternoon after lunch, visit potential customers and try to sell. Next day we would spend the morning cutting the pieces and packing them and carrying them out to the transport people. It was a very small wholesale business where retailers would buy 10 or 15 yards and the big orders were 60 yards and 100 yards, but never very much. It was a hard life but for me a wonderful experience living like that and working so closely with my brother and father.

USA: A dream comes true

Life went on like this for about a year, but the effect of the USIS movies and books was still in me. One of my cousins was in the mail-order business, and I was able to convince him to give me a job selling suits in USA. Haresh helped me to convince my dad, and he allowed me to go. So a year later I reached USA and worked for my cousin’s company for about six months selling suits. After that we started our own company, Crown Creations, with Andy Ramchandani.

Andy was a very good friend from Pune whom my mother treated like a son. She had arranged a mail-order job for him and, at the end of his three-year term selling suits in USA, he stopped in Hong Kong on the way home. When he heard that we were thinking of starting our own mail order business, Andy decided to join. So Andy and I began travelling around the US carrying three or four large suitcases of samples, each weighing 35 kg and more, staying in each city for two or three days and waiting for customers to respond to our letters and advertisements. We would show them our samples take their measurements and send the orders to Haresh in Hong Kong, along with the advance cheques from the customers. Haresh got the suits tailored and shipped them to the customers.

For me, it was such a happy feeling to be in the United States! The only thing I wanted to do was to get a green card soon so that I could live there forever. It was such an amazing country. We were strangers to our customers, staying in a hotel room, and yet they would order suits and never hesitate to write out advance payment cheques. Their confidence and generosity impressed me.

We continued this routine, narrowing our territory to the East Coast and after a few years restricted ourselves between Boston and Philadelphia, and later just New Jersey. Andy fell in love with an American girl, Carol, and they got married.

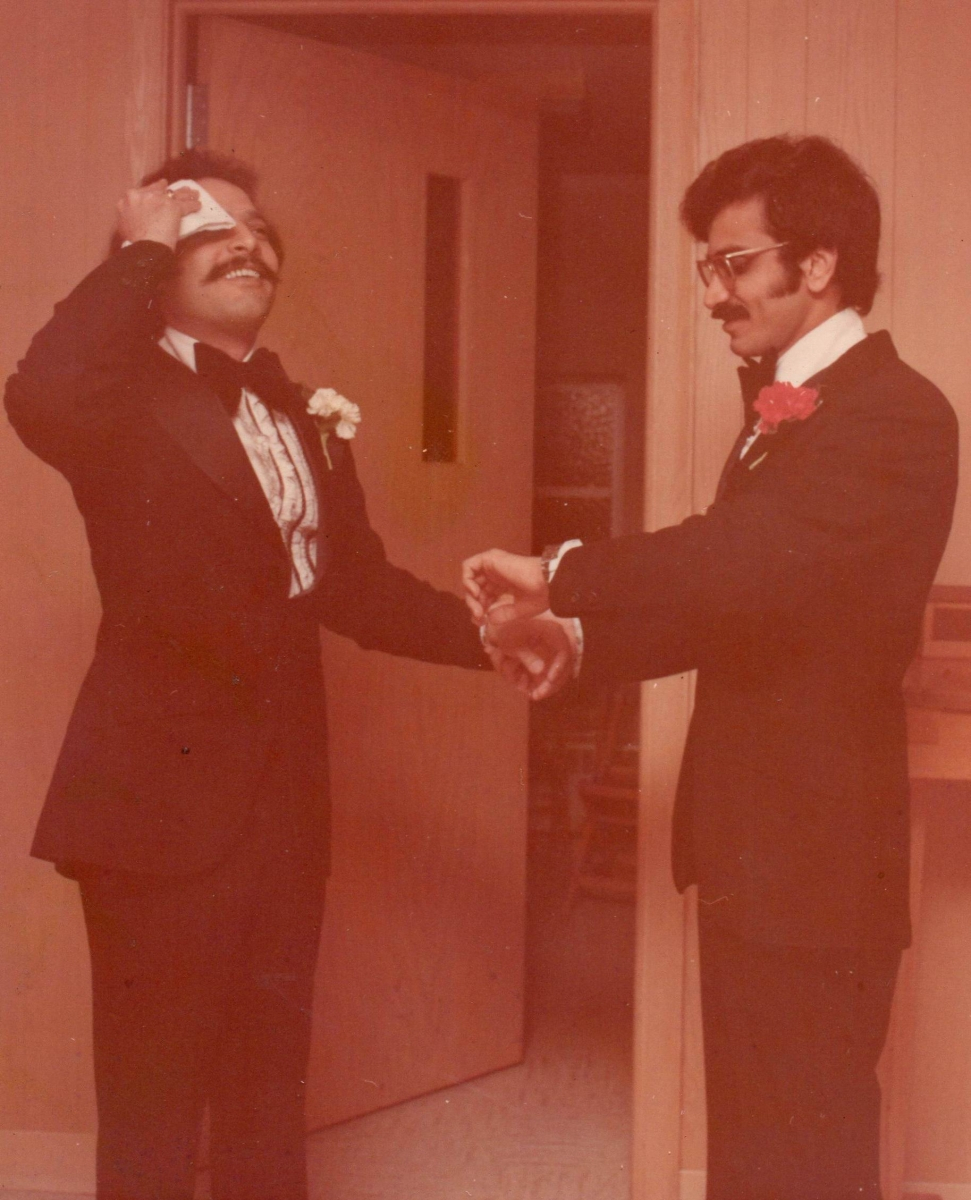

The mail-order boys all dressed up in suits. Andy and Tulsi pose for a ‘my last minute of freedom’ photo just before the wedding ceremony of Andy with Carol.

In the meanwhile, I had gone back to my studies, something I had always wanted to do. Business never interested me much, but because it was important for me to go to work at a young age and help support my family, I had never had the courage to ask my parents to send me to college. In 1973, having worked and saved a little money, I applied to go to an agricultural college in the United States. The reason I wanted to study agriculture was because I had watched documentaries about America growing huge tons of crops with modern technology. When I first visited India in the mid-1960s, there was a big drought where millions of people died because of lack of food, and India had to beg America to send grains. So I think as a young man I had patriotic dreams of studying agriculture so I could go back to India and help solve the food problem. I took admission in the State University of New York in Delhi (pronounced ‘Dell-hi’), and there I studied agriculture for two years.

On weekends I continued selling suits. I also tried to earn money in other ways, working in the school cafeteria where I remember washing 3000 plates every day, which gave me some money and also a free lunch. Then I became a supervisor on the floor where I was staying on campus and this gave me a free room. I helped the professor correct his notes and that also gave me a little money. I was doing everything I could to continue my studies.

In the three-month holiday between the first and second year, I went home to Pune and got married. Among us Bhaibands, there is a strong mindset that when you are a certain age you have to get married. I was 27 years old. It was arranged that I would meet a girl called Maya in Kwality restaurant in Pune. After fifteen or twenty minutes of chitchatting and having coffee, my mother asked me, 'Sooka?'

In Indonesian, ‘sooka’ means ‘like’. None of us realised that Maya, a Bhaiband girl herself whose father and brother had their own business in Liberia, had been to Singapore where she had learnt a few words of Indonesian, and she knew what sooka meant. There was a glow on her face when she heard me reply, 'Sooka!' to my mother. So we liked each other at our very first meeting, and got engaged.

When a new match is made, our families exchange foods and gifts. My mother wanted to send a special dish to my new fiancé’s family and decided on gado gado, an Indonesian delicacy which is a type of salad with a lot of different vegetables boiled individually and topped with a tasty peanut gravy. She spent the morning preparing it and sent it over to Maya’s home. But they had never seen anything like it and just could not understand what it was! My wife Sapna, the name my family gave her when we got married, still makes us laugh by recounting the tale of how much this perplexed them. What did it mean that my mother had sent a strange salad rather than something more traditional? Was she trying to save money? How could they be expected to eat something they had never seen before and had never imagined would exist? In the end, they quietly gave it away to the cleaning woman.

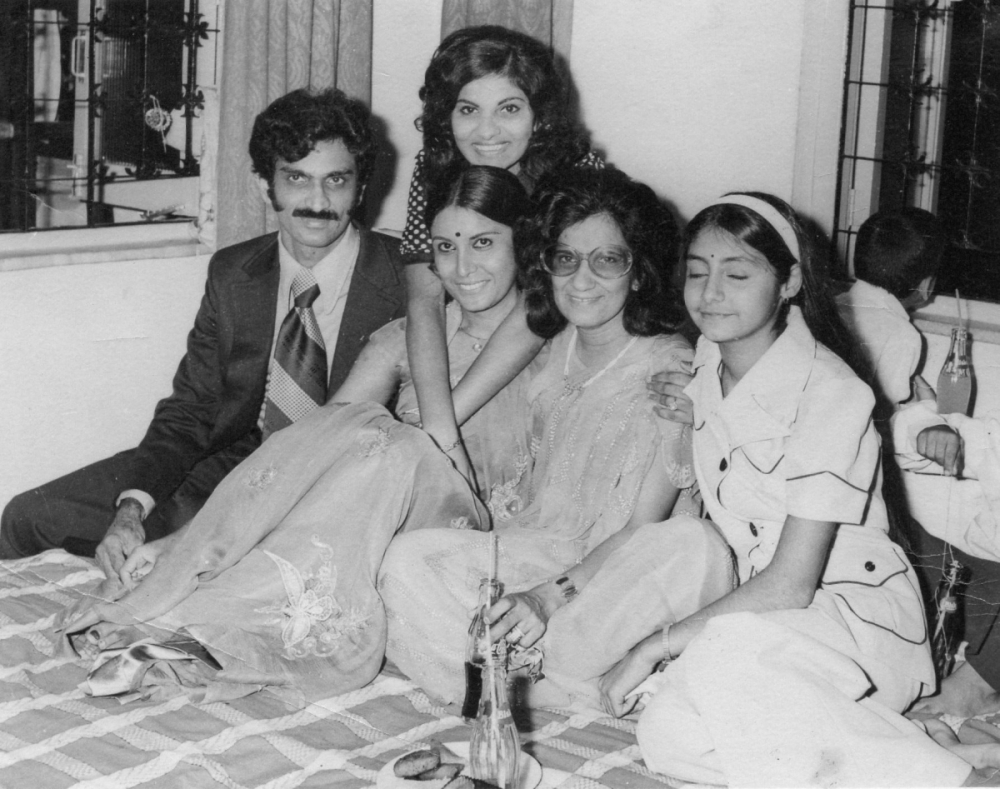

My wife Sapna and me, soon after our wedding ceremony, with two of my sisters and a niece

Sapna and I met on the 4th of August and our wedding took place on the 14th. After the wedding, we went to Bombay and stayed for three days at my aunt’s home. That was our honeymoon, under the watchful eye of my aunt, and eating pani puri at Chowpatty. We went back to Pune and I packed my bags to return to the USA because my visa was expiring. So, just one week after my marriage, I left my wife and went back to the States. Though the families knew this was going to happen, there was still a lot of uneasiness that I may have abandoned her. This did happen sometimes, especially with boys from America, who would get married to American girls, and then under pressure from their parents would marry again in India even though they had no intention of taking the Indian wife to live with them there. In fact, one of my wife’s male cousins had done that. So Sapna’s mother was quite fearful.

That one year, as per our tradition, my wife had to stay with my parents until her visa came through and she joined me in New York on August 12, exactly two days before our first wedding anniversary. By then, I had gone back to work. With no savings left, it was not possible to continue my education. Andy and I opened a small store in New Jersey, selling Indian garments. Though we led a hand-to-mouth existence, Sapna and I look back on it as a very happy time.

In the meanwhile, my brother Jiwat had migrated from Indonesia to Colon, Panama, where his in-laws lived. He had started a business and was doing very well, and, keen that I should also grow to be a big businessman like him, invited me to join him in Panama. He would call every week to talk to me, and would tell me that there were hundred-dollar notes growing on the trees in Panama. All I had to do was come and pluck them! So one day we packed our bags and flew off to Panama.

Panama, where notes were supposed to grow on trees

It was April 1978 when we arrived in Colon. Jiwat lived in a beautiful house, and we enjoyed living with his family and grew very close to them. My brother and his partner had a textile business and for me and the partner’s brother, Suresh, they set up an electronics business, Estee, S for Suresh and T for Tulsi, which is a common way to name Indian businesses.

Colon was a tiny city of about 70,000 people and ten or twelve streets, and moving there from the USA was a big culture shock. The Indians there were not very friendly; perhaps due to the business competition. Being a small place, people were watching each other to see what they were wearing and how they were behaving, which was quite unpleasant after living a free and relaxed life in the USA. In Colon there were no restaurants, no theatres. Our sole entertainment was going out on Saturdays with a group of people and playing rummy. There was one good thing about Panama: our children were born there, our daughter Priya in February 1979 and our son Sanjay in September 1980.

Sanju, Sapna, Priya and me at Iguazu waterfalls, Paraguay

For about a year after we started Estee, we sat and waited for customers to walk in and buy. But business was slow and we realised we would have to try harder. I started travelling across South America to find customers, to Ecuador, Paraguay, Argentina, Chile and Peru. I would travel for two weeks selling, then return to Panama, ship out orders and set out again after two weeks to sell and collect. This went on for about two years. I’ve seen that Sindhis pick up languages quickly. In Hong Kong I had started learning Chinese and here I was soon speaking Spanish. What was hard was collecting money. Things became worse and in the economic crisis of 1982, the South American currencies got devalued and our customers could not pay.

I remember clearly that it started in July because my mother had just passed away. My wife and children happened to be in India, but I had just come back after a month there. I was very lucky that I had seen my mother and got her blessings. Sadly, I could not go for her funeral because business was bad, we were in a crisis, and I could not afford to go back so soon.

We closed our business in Panama. Chile and Peru had become our main markets, and we had customers in these countries who owed us a lot of money. I had taken my wife and children with me on one of the trips. My wife liked Chile and readily agreed to settle there.

Chile, where the grass is always green

It was early November 1983, a week before Diwali, when I brought my family to live in Chile, a depressing time of uncertainty. Suppliers in the Far East had sent us goods in Panama, but our Chilean customers had gone bankrupt. They had bought in dollars at a certain rate of exchange but their currency had been devalued and they now owed two to three times more than what they had bought at. Unable to pay, they had been returning unsold merchandise and I had to get what I could from it. So in December 1982 I registered a new company, Silver Crown, in Chile in partnership with Hiru Datwani, a youngster based in Chile whom I knew to be an extremely nice person, honest and with good business acumen.

We rented a small warehouse for the returned goods, and opened a store in downtown Santiago which Hiru managed. Hiru was kind enough to go stay with a friend, giving us his apartment for two weeks. We were lucky to soon get a beautiful fully-furnished apartment at a reasonable rent. Happy that my family was comfortable, I turned my attention to business, but the situation continued to be difficult, and the store continued to lose money.

In 1984, my sister Sheila’s husband Nari called from Nigeria to say that he too had lost money, was looking to move, and wanted to know if Chile was a possibility. I explained that things were not too good in Chile either and that I myself was looking for other options. We decided to explore the Caribbean Islands where Sindhis had been doing business for generations, flying first to Curacao. We found that a business there would need solid investment, something neither of us could do. In Trinidad the people we met said that visas were difficult. The next stop was Grenada and we stayed in my sister Pushpa’s home and had a really good time. After all, these were resort islands, places people came to enjoy their vacations. However, we soon realised that opportunities on a small island are limited and if we were to open a store, it would be in competition with Pushpa and Prem. We went on to St. Vincent, then St. Lucia, and then the next island, and the next. The last stop was St. Martin where a Sindhi gentleman approached us at the airport and asked if we had come to buy because he had some good deals. Reluctant to move to a place where businessmen were reduced to standing in the airport and hustling for customers, we took the next flight back to Panama.

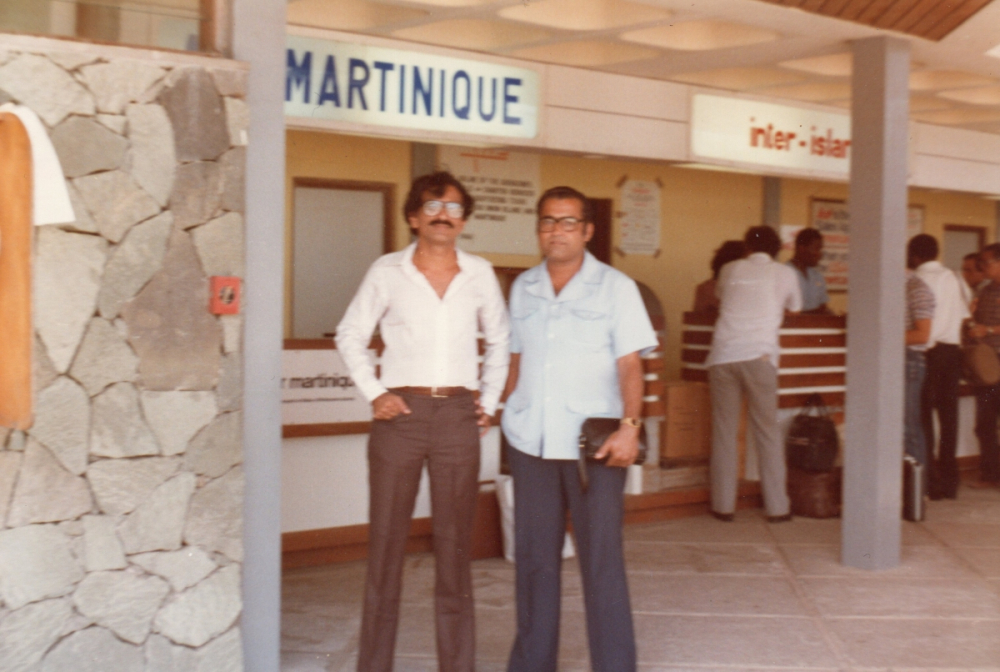

Travelling with Nari from one Caribbean island to the next, hoping to find a place to settle in

Still looking for opportunities, I made a trip to South Korea to explore the possibility of opening a branch of Mulitex there. At that time, Mulitex had branches in Taiwan, Thailand and Indonesia, and my brother was thinking of expanding. This did not work out and I returned home. Eventually, back in Chile, Nari said to me, 'This is a place where people are constantly watering their lawns. The grass is always green. How can such a place be bad?' We both decided to stay on and see what Chile had in store for us.

In Panama, I had been dealing in electronics: televisions, radios, and some gift items. At first they came from Japan; then Taiwan and South Korea began manufacturing. When these countries became expensive, the cheap products from China served the needs of the Latin American markets.

In Panama, we had purchased from the Far East and supplied all over South America with Peru and Chile becoming our main markets. Now in Chile, I was buying from China and Panama, and supplying locally. My store in Santiago was named ‘Muli’, in memory of my mother, whose blessings have fuelled my growth and success. The store was near the Estacion Central and stocked sundry items, from umbrellas to bedcovers to clocks.

In 1985, the economic situation started improving gradually. The big break came when dollar stores became popular, selling a huge range of Chinese products for 500 pesos and 1000 pesos, equivalent to USD1 and USD2. I started importing in bulk at very low prices and selling to the stores and business grew. I opened a store of my own, Todo a Mil (Everything for a Dollar), then another, then another and then started franchising. Within a year, I had eleven stores of my own and three franchised. But this rapid speed of growth made me nervous. I sold the three franchised stores to the franchisees, and over time sold the rest to people who were working for me, retaining just one store and concentrating on wholesale of the dollar items.

In time I was able to purchase my own home. When the next opportunity to buy real estate came I took it and over time bought a number of old houses in a nearby residential area. It had the potential for commercial growth so I set up a showroom and rented the stores at low rents to motivate store-keepers to move there. As the number of stores increased, I set up buildings, a parking lot, warehouses and a wholesale mall. Over time the area has become wholly commercial, and my office and showroom continue to be there. With seven thousand items, wholesaling to the dollar stores continues to be my main business.

My business in Iquique, a beautiful town in the north of Chile, started when I acquired a warehouse in the free trade zone there in an auction bid. The zone was established in the mid-1970s by Augusto Pinochet who took control of Chile with a violent coup against the pro-Communist government of the time. The new government began to nurture the economy with policies formulated by a group of young US-educated economists who came to be known as the Chicago Boys. One of the initiatives was a zone for free trade in Iquique, a town that Pinochet is said to have loved. Jiwat and I went into partnership with K.G. Samtani, who had worked with our father in Tanjung Pinang and all these years had been like a brother to us. In the early 1990s, I opened another business in Iquique, Metro, and acquired another two warehouses. If I have been successful in business, it is largely because I have been lucky to have good people who worked with me all these years both in Santiago and Iquique. Manoj, my cousin Kunj’s son joined me when he was just 17 years old and today, 30 years later, he continues to be my right hand.

Lunch reception at the Presidential Palace in Santiago, in honour of Indian president Shankar Dayal Sharma in May 1995: Pushpa Daswani, me, Indian president Shankar Dayal Sharma, my wife Sapna, Chilean president Eduardo Frei

About seven years after I came to Chile, in a much better financial situation, I went back to the suppliers in Hong Kong and Japan to whom I owed money when I was in Panama. They knew that it was not a case of fraud and that I had lost everything in the crisis. I told the suppliers that I was now better off and ready to start repaying them in monthly instalments from what I was earning. They were surprised because they had not expected this at all, and when I requested them to waive the interest owed they did so readily. My father had always impressed on us the importance of being honest and paying one’s dues and my brothers and I have always done this.

At home in the world

We Bhaibands adapt to any country we settle in and soon develop love and loyalty for the country which gives us our livelihood. Anywhere we travel, we soon feel at home because someone we know lives there, a relative or a friend who will welcome us and make us feel at home. In a way this means we are citizens of the world and there is no strange place. It may be a different place but there will always be a home in that new place. Or we can always build a home in that new place. I have done so, and when I moved on, I always left the past behind without regret or longing. The only country I’ve thought back about is Indonesia, maybe because of the happy childhood memories. It is now 34 years since I came to live in Chile, the most beautiful and welcoming country in the world, which gave me and my family our home.

Today, my parents are no longer with us; my brother Jiwat and sister Chandra are also no more. Mohini, our eldest sister, lives in Pune. Haresh and Ramesh both live in Hong Kong, with their own multinational businesses which they run along with their sons, just as my son Sanjay works with me. Lacha is in Malaga, Sheila in Santiago, Pushpa and Ishu in Grenada and Babe in USA.

The bonds between us are strong and we have passed them on to our children and their children. Our parents’ blessings are always with us. Though we live in different corners of the world, we are in constant touch and we meet as often as we can.

Hardwar: Exploring our roots

I lived in Sindh only for the first year of my life, and have no memories of it. However, I do have strong feelings for those of my community who had to leave the land of our ancestors so abruptly and with no possibility of ever going back.

When I was young I loved to travel, and came to realise that this was a trait I had inherited. My ancestors had been great travellers, adventurers who never let borders restrict them. In their time, travel was tedious and strenuous, and often dangerous too. Yet, they spent their lives in distant lands, with little or no communication with their loved ones at home. I sometimes wondered who these daring, adventurous people were who left their homes to seek their fortunes in faraway lands. One day, completely by chance, I found that they had indeed left a small record of themselves.

I was in India on a buying trip in mid-1998, travelling with my Mumbai friend and supplier Jagdish Daswani. From Delhi he suggested that we take a day or two off to visit Hardwar, and I agreed. Hardwar is a place on the river Ganga, considered to be one of the holiest cities in Hinduism, and is traditionally one of the places where families bring the remains of their dead to be consecrated. To be honest, I went more out of curiosity than as a pilgrim, but that did not stop me from having a ritual dip in the Ganga to wash away all my sins—just in case.

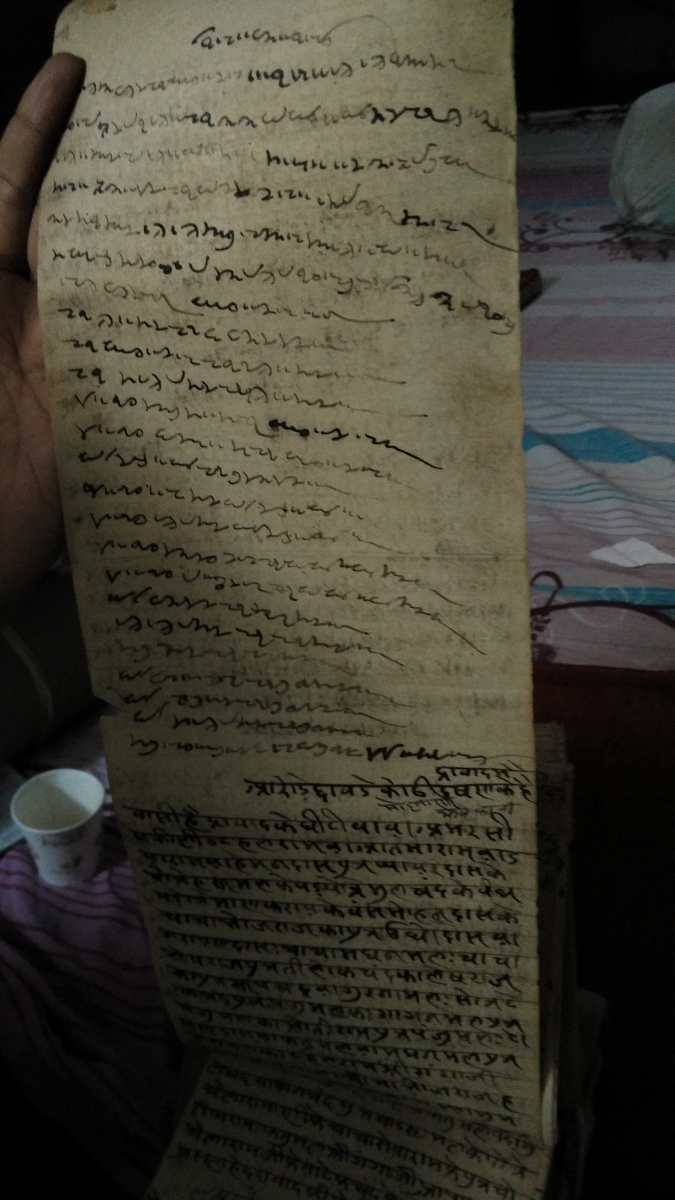

At Hardwar, I was able to locate our family priest, Pandit Balkrishna Sharma, and he showed me the ledgers that his family maintains of visitors to Hardwar. Pandit Sharma comes from a line of hereditary priests who perform rituals at Hardwar. Anyone who visits is invited to write in the ledgers, giving information about their families and the reason for their visit. Pandit Sharma showed me entries made by members of the Mohinani family. Starting from recent entries, we went back over the years and decades. People writing their names and the purpose of their visit would also mention the names of their male relatives. Using this information, we were able to keep going back in time, all the way back to the ancestor Mohan from whom we got our family surname, Mohinani. When Mohan died, his son Moolchand brought his ashes to Hardwar and wrote in the register, 'From this day onwards, I and all my descendants will be known by the name Mohinani, in memory of my father Mohan.' I took a photograph of this historic entry but to my great regret, lost it. In those days, digital photography was new and the photos of that trip all got deleted by mistake.

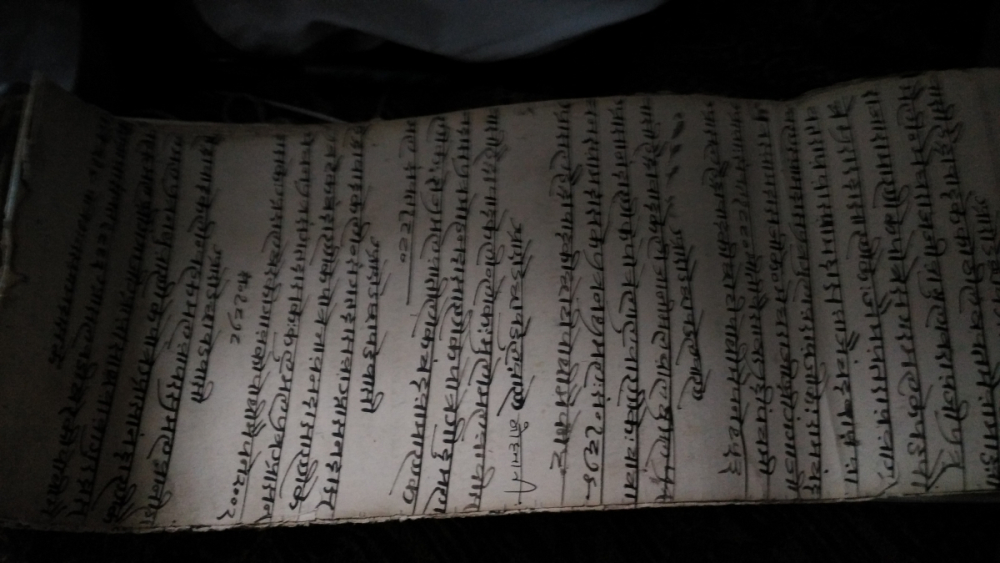

In the years to come I visited Hardwar a number of times and read my ancestors’ entries with fascination. It was an intensely emotional experience seeing their handwriting, the three different scripts (Sindhi, English and Hatvanaki) in which they wrote and their signatures, and trying to imagine the kind of people they were and the kind of lives they led. Some fascinating family stories emerged, and we were also able to construct our family tree. However, I never again saw the page with Moolchand’s entry though I searched for it on every visit and continue to do so. Many of the old papers have decayed and torn and are preserved in bundles of tatters. Some old entries have been copied on to fresh paper.

This entry from my ancestor Moolchand when he visited in Sindhi Samvad 1880 (c1824), is one which has been copied recently

The most ancient original record from our family is written in the handwriting of Moolchand’s great-grandson Tahilram of Ghiti Amarsingh, Hyderabad Sindh, and is dated Sindhi Samvad 1939 (c. 1883).

Once our family tree was complete, I decided to start another project: to make a directory of all the Mohinanis all over the world. One reason for this is that I would like to fund Mohinani youngsters without their own means through their education. I myself craved for an education but did not have the means to pursue it and I would like to support any young Mohinani who wishes to be educated.

The inner journey

As children, we never received religious instruction. Although we were never taught to say prayers, we knew that our parents were religious people. Our school in Tanjung Pinang was run by Catholic nuns. My friends were Muslims. In Medan, my grandmother and aunts had fixed prayer routines and we often visited the Gurudwara next to our school. In Pune we had a small altar in our house with images of Hindu gods.

Our elders never called us to sit and pray together with them, but the way they prayed was so sincere and heartfelt that it created the same sort of feeling in us. That’s the sort of feeling I have tried to pass on to my children and grandchildren.

My first exposure to the Radha Soami teachings was through my father, who was a devout follower of the Radha Soami spiritual movement. One day, on a visit to Pune, I asked him why he never went to the Dera at Beas to see the Master. His answer was very simple. He said, 'I don’t really need to. I see him inside, every day.' It was years later that I understood for myself that, with proper meditation, the master shows his radiant form to the disciple.

My father never talked much about it but every time I left to go back abroad, he would give me a Radha Soami book saying, 'Read this whenever you get time.' I gradually became attracted to the path, which preaches a high moral life and the daily practice of meditation. Other important aspects are giving up non-vegetarian food and abstaining from alcohol and intoxicants. Both my wife and I are devotees and we have been given ‘naam’, which is a process of initiation in which we learn the technique of meditation, sitting still in silence and listening to an inner sound to attain a higher state of spiritual advancement. We have both experienced an inner transformation and have committed ourselves to the cause.

My wife and I have faced our share of life’s tragedies. Through all the disappointments and through the everlasting sorrow of our daughter’s untimely death, the teachings have helped us to find solace and equilibrium.