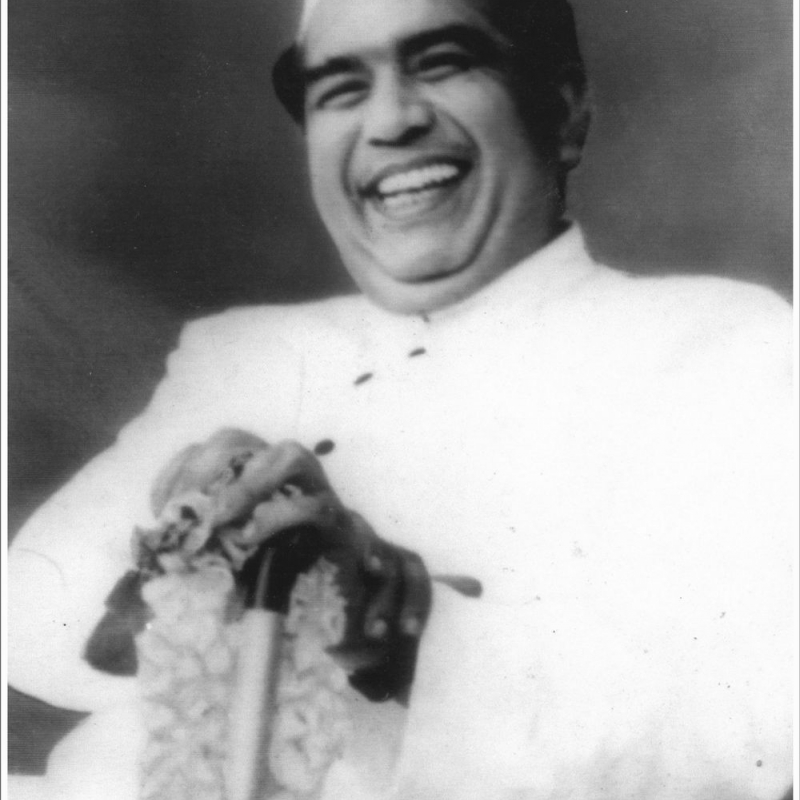

Bhai Pratap was not just a Sindhi hero. Given the magnitude of his achievements, the extent of his culture and learning and the impact his decisions and actions had on others, Bhai Pratap was a hero of humankind. And yet, there are no memorials or tomes that commemorate his extraordinary life. He was an entrepreneurial genius who as a young man had to give up his education to turn around a floundering family business, expanding it into an empire with strong footholds around the globe. In time, he had access to heads of state in the countries where his concerns were located and a few of them became his friends. He was a stalwart of the Indian freedom movement, funding the Indian National Congress, conducting seditious activities against the British crown from the basement of his home and hosting Mohandas Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and others when they visited Hyderabad, Sindh. When it came to philanthropy, Bhai Pratap was nothing less than a spendthrift.

All this, however, paled in the face of his life’s biggest work, rehabilitating the Hindus of Sindh displaced by the Partition of India in 1947, a tremendous effort unparalleled by any individual in history. Then, it was his economic vision that led to an awareness of the concept of zones for duty-free export in independent India, and the establishment of the first such zone at Kandla.

Despite all his contributions, Bhai Pratap’s sun sank suddenly and without warning, a Greek tragedy for a Greek god of a man. Imprisoned on an economic charge, five years passed before he was exonerated, pardoned and released—but it was already too late. Less than two years later, Bhai Pratap died, alone and far from home. He was just 59. Family members felt the disgrace as long as they lived. The whispers against him, vague and baseless as they were, continued for so long that they wiped out every trace of his magnificent achievements. It is only in the twin cities of Gandhidham and Adipur, the flourishing towns that he founded in Kachch (Kutch), that he is still reverentially remembered with appreciation and gratitude.

Origins

Bhai Pratap Dialdas Nanwani was born on April 14, 1908 in Hyderabad, Sindh, into a Bhaiband family. The Nanwani surname comes from an ancestor, Bhai Nanumal. Nanumal was Bhai Pratap’s great-great-grandfather: Pratap was son of Dialdas, the son of Moolchand, the son of Hemandas, the son of Nanumal (Advani 1919).

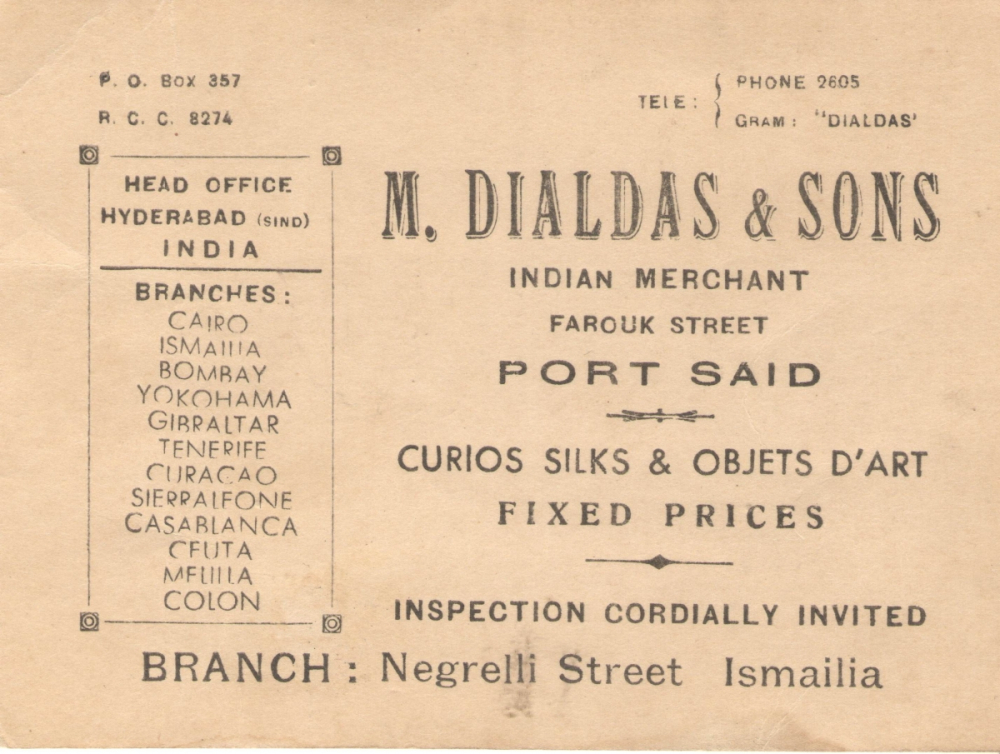

Bhaibands generally identified themselves with their name, given along with the name of their father, or the initial of his name. The British introduced the practice of using surnames and because of this, many Sindhi families derived their surnames from the father of the person who first filled a British application or census form. Bhaibands have always tended to honour tradition, and many continued to go by the father’s name even after a surname had been established. So Bhai Pratap is better known as ‘Pratap Dialdas’ than ‘Pratap Nanwani’ and his father’s stores were ‘M Dialdas’ rather than ‘Dialdas Nanwani’.

No records with information about Nanumal or Hemandas have yet been traced, but it is believed that Bhai Moolchand, Pratap’s grandfather, met an untimely death resulting from a fall from his horse. He was thirty-two years old (Advani 1919).

It was 1862, and the British had annexed Sindh to their Indian empire just 19 years before. An enterprising young man, Moolchand had worked as a government contractor, bidding for and winning tenders to construct roads and buildings as the British modernised the city of Hyderabad. It is said that Moolchand’s work had been profitable. It is certainly true that no ordinary Hindu of Sindh would have been riding a horse in those days. However, when he died his widow was left with no income and four young children to bring up: Shewakram, Dialdas, Ratanchand and a daughter (Advani 1919).

Neither Moolchand’s wife’s name nor his daughter’s name is known—it was a time when women did not have a public identity. Their childhood names would be changed when they got married. When their first son was born, they would be identified as the mother of the boy.

To bring up her children must have been a terrible struggle for Moolchand’s widow (who was perhaps known within the family as ‘Shewak-ma’, the mother of Shewak). It is said that she shopped for vegetables for her family at night, buying leftovers and unsold items to get lower rates. However, this did not change her fundamentally generous nature. She loved birds and made sure that she fed them every day, throwing grain to them or putting food out on a ledge, a practice that elderly Sindhi women follow even today. If she found a sick or injured bird, she would nurse it back to health (Advani 1919).

Pratap’s father Dialdas, orphaned at an early age, went to work when he was just 12 or 13 years old. Starting off as a cleaning boy in a Hyderabad shop, he soon began trading and within a few years he had set up his own shop selling indigenous headgear (Advani 1919).

Dialdas first went on Sindhwork at the age of 18. Whether he set out as a peddler with his own goods or whether he initially worked for another concern, is not known. It is believed that he was mentored by a prominent businessman of the time, Bhai Moolchand Kirpalani, whose flourishing ivory business had earned him the title ‘Aaj Waro’, the ivory specialist (Advani 1919). Dialdas began operating in Gibraltar in 1870 and his store, M Dialdas, was registered there in 1890 (Merani & Laan 1979).

Bhai Dialdas had never been to school and could read and write no language other than Hatvanaki. However, he was abundantly successful in business and in time was running stores and offices in many countries. M Dialdas has been noted as the first Bhaiband trading establishment to appear in Sierra Leone in 1882 and could well have been a pioneer in other locations too (Merani & Laan 1979).

When Bhai Dialdas died in 1921, his four sons Naraindas, Pratap, Harkishindas and Balram inherited a significant business empire. Pratap was just thirteen; Harkishindas and Balram even younger. Narain, though only twenty-two at the time, had already been working with their father and was steeped in the business (Advani 1919).

Narain, unlike his father Dialdas, was known to be something of a princeling, flamboyant and bighearted. Bhai Dialdas, who had inherited his mother’s disposition to care for the needy and destitute, made regular visits to the civil and mental hospitals of Hyderabad to see to the care of their inmates. He took charge of unclaimed dead bodies and arranged for their cremation and even performed their last rites himself. Like his mother, he loved birds and had opened a bird hospital. People knew of it as also of his ashram for the poor and aged at Phuleli but he refused to put his name on them, preferring to make his donations anonymously. It was the year following his death that Narain built ‘Bhai Dialdas Park’ and ‘Bhai Dialdas Club’ in Hyderabad (Advani 1919); the latter still stands today.

Dialdas Club, Hyderabad, a venue for parties and wedding receptions in 2016. Photographed by Saaz Aggarwal, February 2013

Bhai Narain too was known for his generosity and his inclination to live life to the full. S.K. Kripalani, one of his best friends at school, writes in his memoirs of a meeting with Narain at Port Said. Kripalani was sailing from Bombay to Dover and when the ship called at Port Said for 12 hours, Narain came on board to meet him:

Narain insisted I dine with him. I demurred because I was sort of attached to the Baroda party. Without a moment’s hesitation he said that, in that case, he would invite His Highness also! The respectful but assured manner in which he asked HH to give him the honour of his company at dinner impressed me no end. HH said his programme was in the hands of his staff, so Narain marched to the cabin of the Maharaja’s diwan. He had already invited a number of friends to dine with His Highness. Narain solved the problem by inviting all the First Class passengers, men and women, some 300 strong, to dinner at the Casino. The dinner party was one fit for royalty. The food was delicious and drinks, including champagne, plentiful. Narain paid a bill of over 1500 dollars, an enormous sum in those days, without so much as batting an eyelid. (Kripalani 1993)

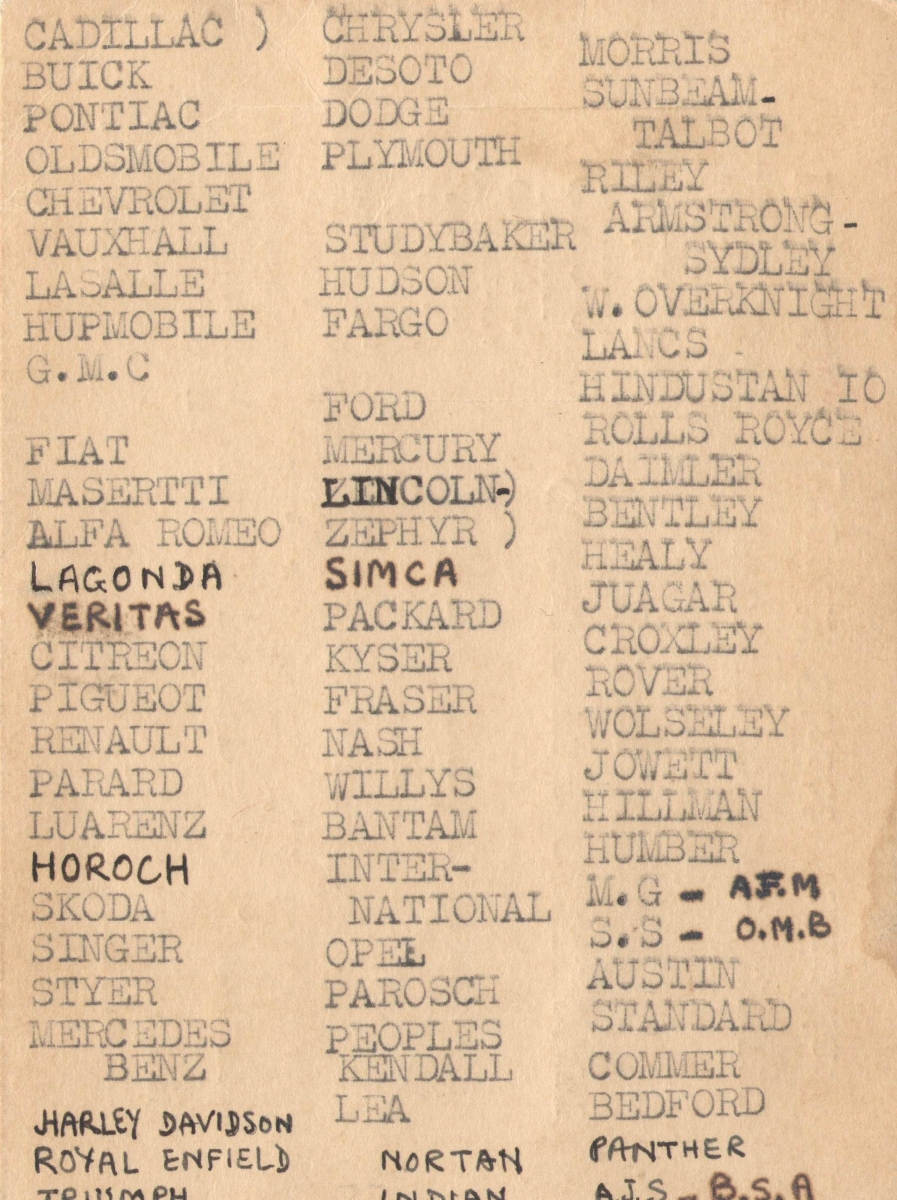

In 1919 when this incident took place, Narain was just 20 years old. He had been born into the lap of luxury and when the Maharajas of India were in need, they well knew which few Indian families could tide them over by purchasing their family jewels (Hiranandani 1980). It was Narain who bought the first car to be seen in his home town, Hyderabad. It was he who established the firm’s perfume factory in Paris. Tragically, Narain is said to have lost his life to appendicitis at the age of 28. Pratap, just 20, had no choice but to discontinue his education and take over the business.

A man of the world

The years between Dialdas’s death and Narain’s had shaken the foundations of the business and Pratap worked hard to consolidate, build loyalty back into his teams and continue expanding. M Dialdas had outlets in Yokohama, Kobe, Canton, Hong Kong, Bombay, Karachi, Port Said, Cairo, Ismailia, Sierra Leone, Marrakesh, Fèz, Larache, Casablanca, Rabat, Meknes, Gibraltar, Tenerife, Las Palmas, Melilla, Ceuta, Curaçao, Colón, Panama City and doubtless several more not listed on the advertisements from which these names are noted. The head office of M Dialdas remained in Hyderabad, Sindh, and was a landmark in the city.

M. Dialdas post card (front and back), Port Said. From the collection of Manjari & Vashu Kriplaney, courtesy Pratap Kriplaney-Dialdas

Bhai Pratap’s education may have been rudely interrupted, but his insatiable thirst for knowledge led him to continue studying and learning throughout his life. He may have been travelling primarily for business, but he used his travels to gain knowledge too. With a number of business outlets in Egypt, he made the time and effort to study the pyramids and ancient mummies and became an expert on the ancient civilization of the Nile Valley. His fascination was partly linked to the relatively recent discovery of the ancient Indus Valley civilization with a huge site in Sindh, and how its secrets could be uncovered using the knowledge and techniques applied in Egypt. He is also said to have been a keen student of astronomy, archaeology and architecture (Hiranandani 1980).

At a tender age Bhai Pratap established himself as one of the prominent citizens of Hyderabad. Traces of his philanthropy are visible in Hyderabad even today; so many years after Sindh evicted its Hindus. The Government College, Hyderabad (known as Dayaram Gidumal College in Bhai Pratap’s time) still has the Bhai Dialdas Moolchand Library built with funds donated by him and named after his father; and a hall, which now houses the Physics department of the college, in memory of his brother Naraindas. These endowments date back to 1936 when Bhai Pratap was 28 years old.

Bhai Dialdas Moolchand Library Hall. Photographed by Yousuf Nagori, October 2016

The Narain Dialdas Hall, on the upper floor of a building next to the Dialdas Moolchand Library Hall, houses the Physics Department of Hyderabad College. The college is being renovated and the plaques are also being restored. Photographed by Yousuf Nagori, October 2016

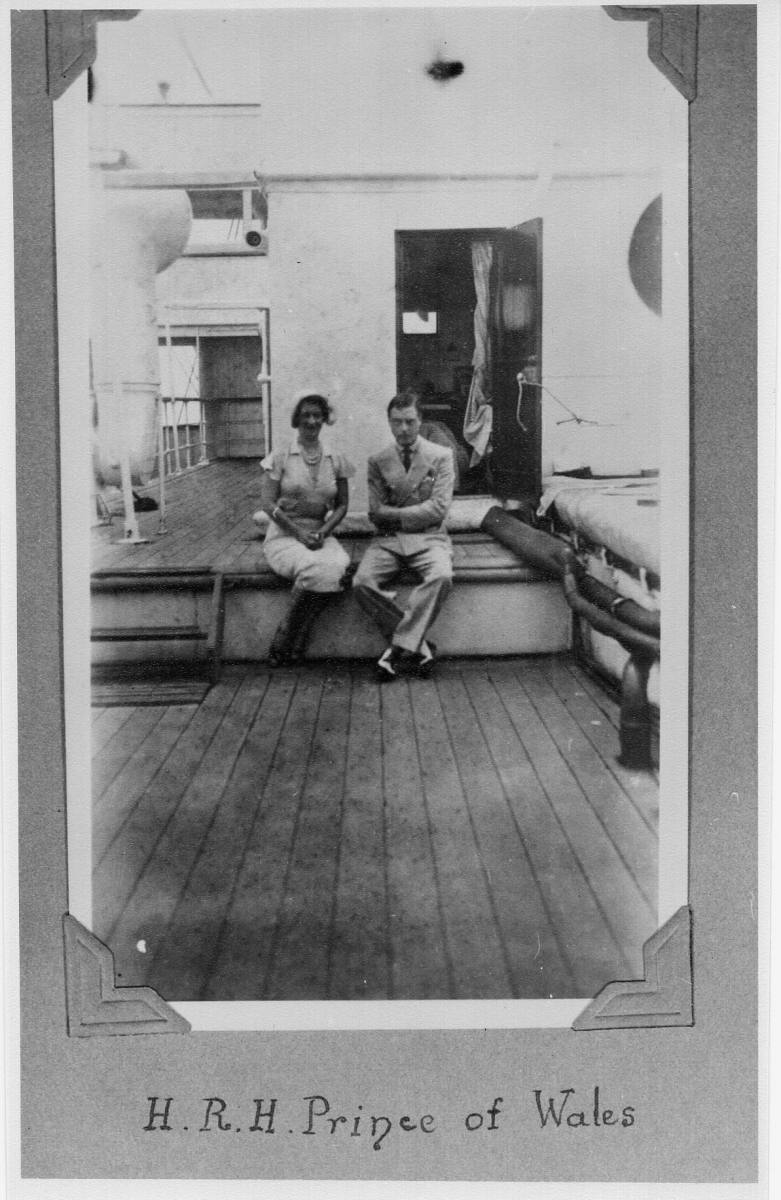

As Bhai Pratap’s stature grew, he began to associate with statesmen and hosted many Indian leaders in his home. In his travels around the world, he became acquainted with the Prince of Wales, who would later become King Edward VIII. In later years, when Jawaharlal Nehru wanted to send a copy of his book to Mustafa el-Nahhas, former Prime Minister of Egypt, he sent it via ‘Mr Dialdas’ in Port Said (Nehru 1958).

Bhai Pratap was a keen photographer. He took this photo of Wallis Simpson and Edward, Prince of Wales, on board a ship they were on c. 1940s. From the collection of Manjari & Vashu Kriplaney, courtesy Pratap Kriplaney-Dialdas.

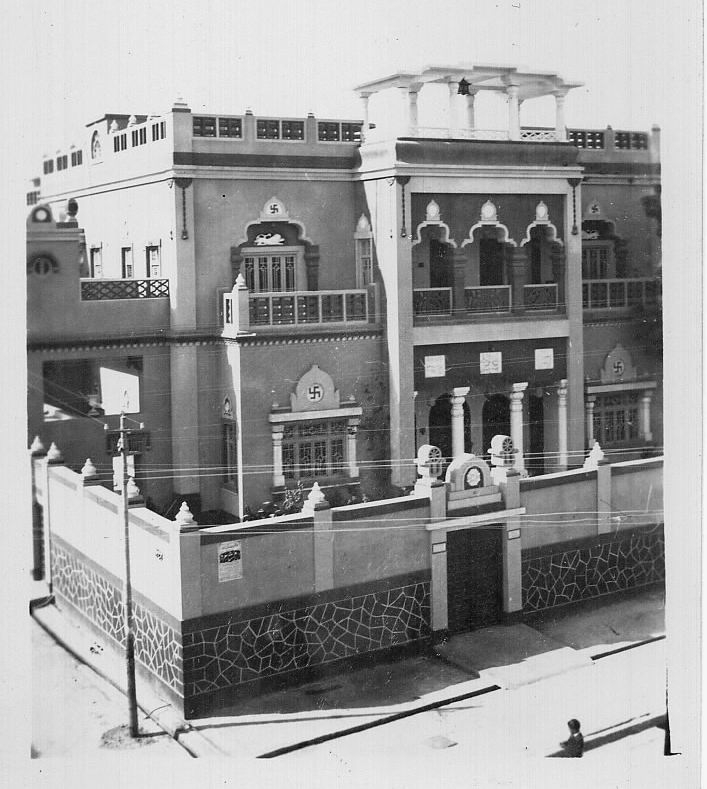

Maitri Bhavan, Hyderabad c. 1940s. From the collection of Manjari & Vashu Kriplaney, courtesy Pratap Kriplaney-Dialdas

Bhai Pratap’s home in Hyderabad, Maitri Bhavan, also became a place of legend. It is said to have been inspired by the Birla Temple, and had galleries and balconies like those of the Moghul palaces. In the middle of the drawing room was a havan kund, a pit to be filled with logs that lit the ceremonial fire when a pooja was performed. It was decorated with temple bells, large paintings and antique sculptures. Other merchants may have dealt in Indian knick-knacks merely for commercial purposes, but Bhai Pratap was one who would never hesitate to purchase a curio for his own enjoyment (Hiranandani 1980). His fascination for knowledge, history and art led him to build a formidable collection of antiques and artworks, sculptures, Buddha statues, ancient books and manuscripts, even the hand of an Egyptian mummy, and paintings by artists such as Jamini Roy, Nandalal Bose and Rabindranath Tagore.

Bhai Pratap was a voracious reader and he would stay up late reading about the history of Sindh, art, metaphysics, the life and teachings of Lord Krishna, Gandhi, Buddha, Engels and Freud. He loved photography, as well as music—both Indian and Western. For Bhai Pratap was not just a sophisticated cosmopolitan with western tastes, he also was a passionate nationalist.

Freedom—followed by loss

In the fight for freedom from British rule, it would surely have been easier for a businessman, conscious of which side his bread was buttered, to prefer to side with the masters. Bhai Pratap, on the contrary, had no qualms about being fully on the side of the patriots who wanted the British out as soon as possible. As early as January 1933, when Bhai Pratap was just 25 years old and still in the process of restoring and expanding the family business empire, records show that he was one of a handful of citizens who applied for and were granted permission to visit Gandhi during his incarceration in Yerwada Jail, Pune.

Gandhi had introduced movements of social reform and these, too, were strongly supported by Bhai Pratap, both through monetary donations as well as with enthusiastic personal participation. These included uplifting the oppressed Hindu castes, considered ‘untouchable’ and named ‘Harijan’ or ‘God’s people’ by Gandhi; and nationalistic projects such as spreading Hindi across India as a link language.

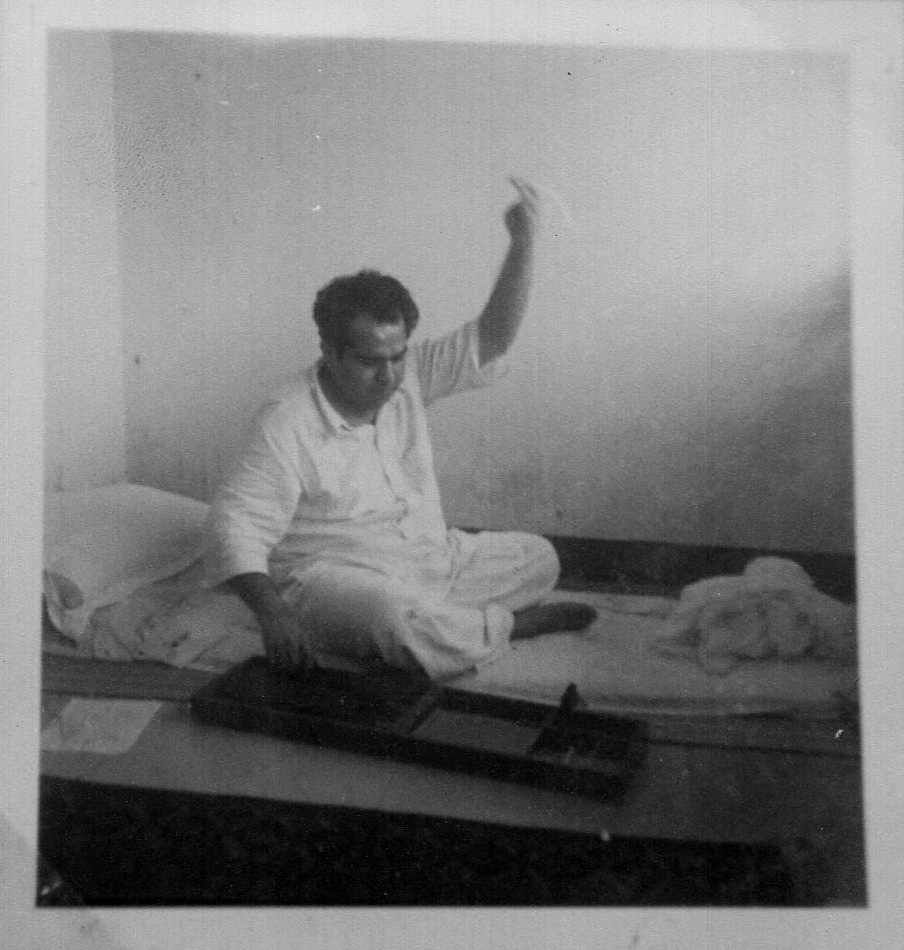

Bhai Pratap spinning cotton. From the collection of Manjari & Vashu Kriplaney, courtesy Pratap Kriplaney-Dialdas.

The Hyderabad District Congress Committee was dependent on financial contributions from Sindhwork merchants and Bhai Pratap was one of the most prominent (Markovits 2000). When Gandhi, Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Prasad, Aruna Asaf Ali and other leaders of the All India Congress visited Sindh, he hosted them, providing funds, volunteers, transport, meals for all, and other requisites. Senior Congress leader J.B. Kripalani describes one of his most tense moments during the freedom struggle, his imminent arrest after Gandhi’s inflammatory speech announcing Quit India, and specifies: ‘As for the funds that would be required, I asked Sucheta [Kripalani’s wife] to seek the help of Bhai Pratap Dialdas, a Sindhi friend (Kripalani 1970).’

With the call to ‘Quit India’ in 1942, the eagerness for independence swept with rapid energy over the nation. Very soon most of the leaders of the freedom movement were captured, and remained imprisoned by the British right through the remaining years of the Second World War. At this delicate time, the basement of Bhai Pratap’s home in Hyderabad is said to have been a major centre for underground activity. Pamphlets to arouse nationalistic fervour were printed and distributed from there. Currency notes were stamped with the slogan ‘Quit India’ and quietly put back in circulation to create awareness and inspire every Indian who used them, which greatly infuriated the befuddled colonial government. Those leaders of the freedom struggle who had managed to escape British capture were in hiding and it is said that Bhai Pratap even hosted some of them at this time (Hiranandani 1980).

The All India Congress office continued to function in secret in Bombay and Bhai Pratap not only donated but also got some of his friends to participate. Young, fashionable and seen as wealthy playboys who had never known the need to work or shown any interest in politics, they would have been considered above suspicion by the police, and were able to circulate the ‘seditious’ literature and messages to the various state units. These were activities of great risk (Hiranandani 1980).

India’s struggle for freedom, in conjunction with the events of world history, did eventually lead to independence from British rule for India. However, the Sindhis paid a terrible price. While other border provinces of India like Bengal and Punjab were partitioned and a portion given to each new country, Sindh was given intact to Pakistan. Hindus had been a minority in Sindh for centuries—unlike most other parts of India where they were a majority. They had adapted and lived comfortably all that while and it was assumed that they would continue to do so. However, the events following Partition soon made it clear that the new nation of Pakistan had no place for them. Escaping the riots, they poured out of Sindh by every means available, a growing stream of refugees.

Bhai Pratap moved his head office from Hyderabad, setting up one in Bombay and one in London. He located himself in Bombay and began doing everything he could for the refugees. When a family known to him arrived at the Bombay docks in a ship that had left Karachi a few days before, he would go personally to receive them, or send his brother Balram to do so. With his own home filled to overflowing, he borrowed vacant apartments from his friends to house the fleeing families. Each was given a room for one week, giving them time to make their own arrangements and move out, leaving the room for another family which needed a temporary home. During that week, food cooked in the kitchen of Bhai Pratap’s own home was delivered to the families for every meal. In an era of joint families and before birth control, each of these included elders and a fair number of children.

Bhai Pratap also took under his wing thousands of families Bhai Pratap took under by generously supplementing the new Indian government’s efforts. Those fleeing Sindh with no recourse were being housed in the Second World War army barracks recently vacated by the British, at locations across the west and north of India. Many of those herded into these ‘refugee camps’ were well-off Hindu Sindhis who had left their comfortable lifestyles and everything they owned behind. Bhai Pratap donated hundreds of beds to the camps so that they would not have to sleep on the floor. With an ancient tradition of needlecraft, the women of Sindh were by and large skilled seamstresses. He donated hundreds of sewing machines to the camps so that they would, with a familiar activity they cherished, have a means to support themselves and their families. For the same reason, he negotiated with the new government of Bombay State to allow his people to peddle goods in public places without a license (Hiranandani 1980).

As always, his measures went far beyond writing cheques for food and there was a discernible sensitivity and sustainable thinking behind his efforts. It has been said by many that there was never a single instance when someone came to him for support for a new venture and was turned away. When the board of Hyderabad’s Dayaram Gidumal College decided to start afresh in Bombay, establishing National College, he was the first to contribute. It was the same with the Sindhi newspaper Hindustan (Hiranandani 1980).

A new phase

When Partition came, Bhai Pratap was 39 years old. It was at around this age that Bhaiband men traditionally stepped into the next phase of their lives, moving back to live at home and handing over their international businesses to their sons. Bhai Pratap had no sons so he gave the management of his businesses to his brothers and their sons, and occupied himself with the rehabilitation work.

Bhai Pratap may have had no sons, but he did have four daughters. However, for all his educated mindset and forward thinking, he had always followed the traditional Bhaiband practice of involving the young men of the family in business and keeping the young women, even those with strong capabilities, away from it. It was firmly believed that daughters’ destinies lay with the families into which they married.

By tradition, the family fortune (and all its challenges) would be inherited by sons while daughters would be settled with ample dowries at the time of their marriage. However, Bhai Pratap was under the influence of Gandhi’s reform movements. One of these was to abolish the tradition of dowry, a true evil which drove many ordinary Hindu families to ruin. As a prominent citizen, Bhai Pratap’s behaviour was always under scrutiny. To set the right example, he publicly disavowed dowry. And so his daughters received no dowry.

It was 1927 when Bhai Pratap and Lachmibai Dialdas (nee Kirpalani) were married; as per the tradition of the time, both were still teenagers. Their daughters were all born in Hyderabad. As children in a traditional Bhaiband joint family, the eldest two, Nirmala and Sundri, spent long stretches of time of their childhood with Narain’s family in Japan, growing very close to Narain’s widow Radhibai and her daughters Jasoti and Mohini. Nirmala married Wasudeo Hari Patwardhan, affectionately known in the family as Balu Dada. She had studied art under Nandalal Bose at Shantiniketan, and after her marriage continued with her education, specialising in ceramics with European and British artists. She emerged as one of India’s foremost ceramic artists, celebrated through her work and the work of her students.

Sundri and her younger sister Manjari both had traditional Bhaiband arranged marriages. Sundri married Harkishin Bhojraj Chanrai, from a family with big business interests in Africa, and spent her life in Lagos and London. Manjari’s husband, Vashdev Lokumal Kriplaney, from a family of Calcutta jewellers, ran a branch of M Dialdas in South America. After 15 years in Caracas and Curacao, they moved back to India, but eventually settled in Las Palmas. When Vashu died in 1977, the eldest of their four sons was just 11 and Manjari single-handedly brought up the boys. Bhai Pratap’s youngest and only surviving daughter, Aruna, was born 13 years after Manjari. She married Suresh Mohan Jagtiani, a Bombay-based entrepreneur and businessman from a Sindhi Amil family.

During the years Bhai Pratap was building Gandhidham, Adipur and Kandla Port, Manjari was an unmarried young woman and Aruna a tiny tot. Both grew to love the place and in later years shared nostalgic memories with their children. As with everything he did, Bhai Pratap involved himself fully, making strategic plans, hiring world-class professionals and contractors, campaigning widely to bring displaced Sindhis to make their homes there. Plot and construction were offered at the lowest possible rates.

When people came to live in Gandhidham he did all he could to make them comfortable. At first it was truly a wilderness, crawling with snakes and scorpions, and people were hired and paid a small fee for each creature they killed. As the town became populated and a neighbourhood developed, Bhai Pratap would visit, carrying saplings to distribute. He would enter a home and ask the family, 'How many children do you have? Here is another child for you to look after!' Today, nearly 70 years later, Gandhidham is green and fertile, a modern Indian city with every facility from trade opportunities to high-quality education. Kandla hosts one of the major ports of India. Land prices compare with those in the big cities of India. It took decades, and Bhai Pratap never saw the tremendous success of his last major venture.

The new homeland

As early as October 1947, months before the worst atrocities against the Hindus erupted in Sindh, Bhai Pratap had already started his search for an alternative homeland for the displaced members of his community. Kachch was the area most geographically, culturally, and linguistically akin to Sindh. Large parts of Kachch were uninhabited and uncultivated. Kandla creek, on the coast of Kachch, had the potential to be developed as a major international port between Karachi and Bombay for the Sindhi businessmen to continue their trade unhampered.

Kachch was a princely state, and Bhai Pratap approached its ruler, the Maharao Sir Vijayarajji Bahadur for a grant of land for the homeless Sindhis. Bhai Pratap explained his vision of using private enterprise to develop the region. He would set up a corporation which would create infrastructure of every kind, including a port at Kandla, opening opportunities for growing prosperity to the people of Kachch. The project had Gandhi’s blessings and the Maharao generously pledged 15,000 acres to the corporation on a perpetual lease, free of cost (Anand 1996). Work began, while the legal processes were carried out in fits and starts.

Bhai Pratap visualised the new homeland akin to the structure of the Bhaiband lifestyle: Gandhidham would be the commercial centre, Adipur would be residential and Kandla the port where goods were received and dispatched. He entered into the project phase with enthusiasm, initiating the process of bringing the railway line to Gandhidham, building roads and an airport and creating a water supply for the isolated desert town. To build homes, he hired the well-known Italian architect and urban planner, Mario Bacciocchi. Having learnt that plans to develop Kandla Port had been prepared some decades previously by a Scottish port engineer, Bhai Pratap got his London office to locate the engineer. He requested the engineer to send him his reports, which he did, along with maps of Kandla (Bhavnani 2014).

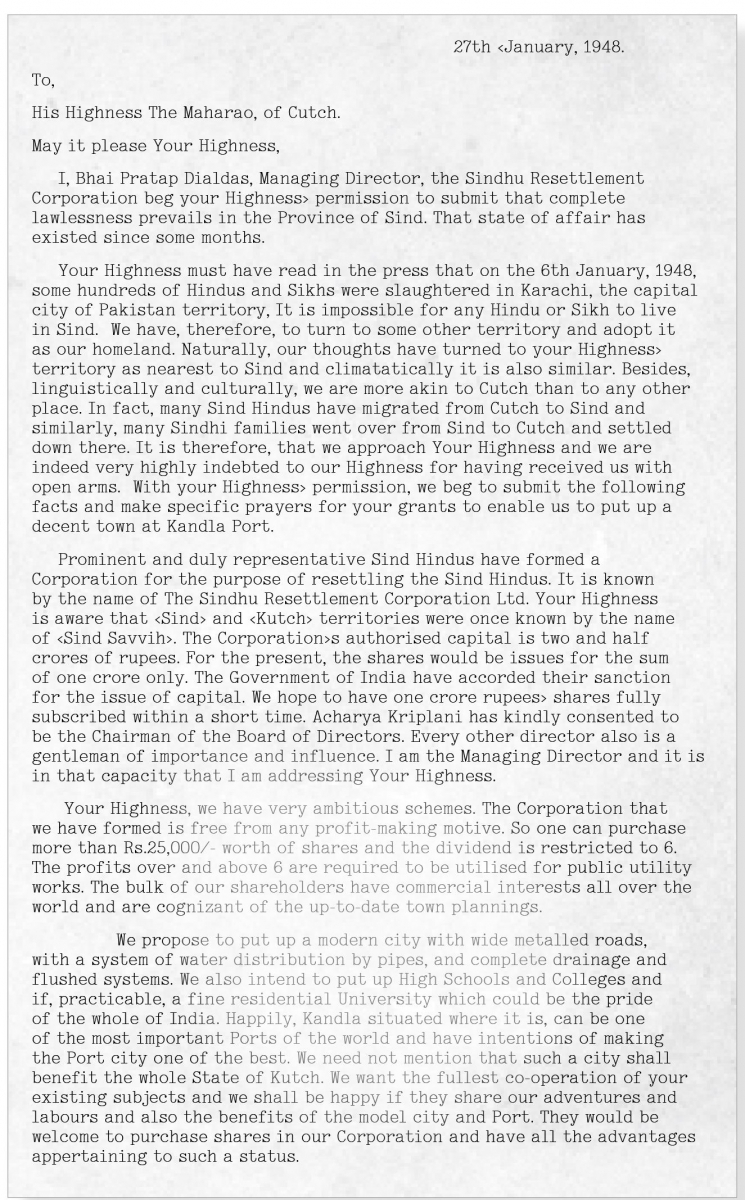

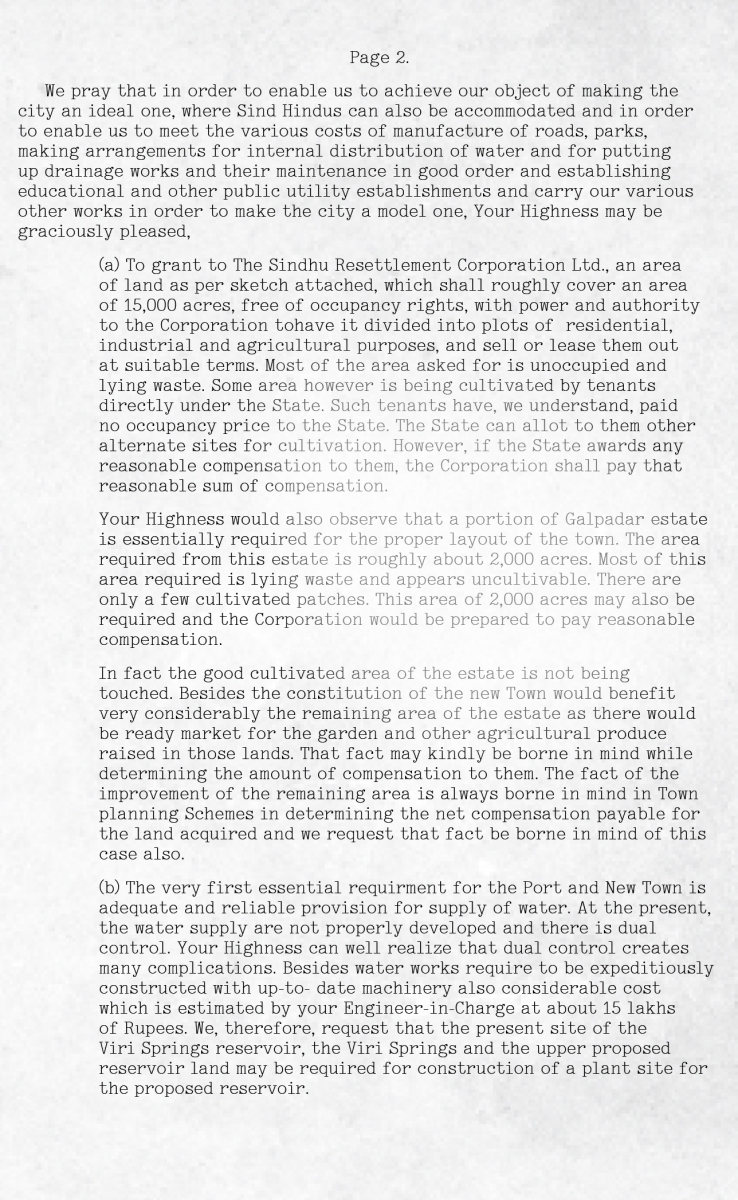

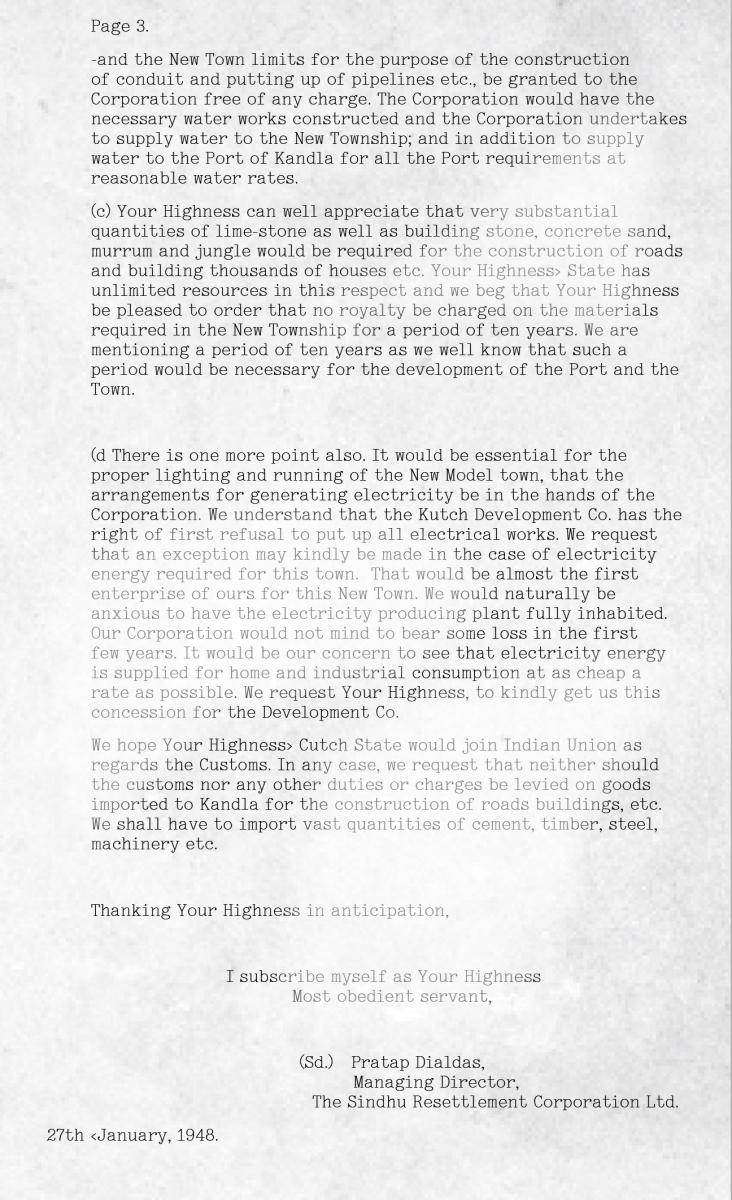

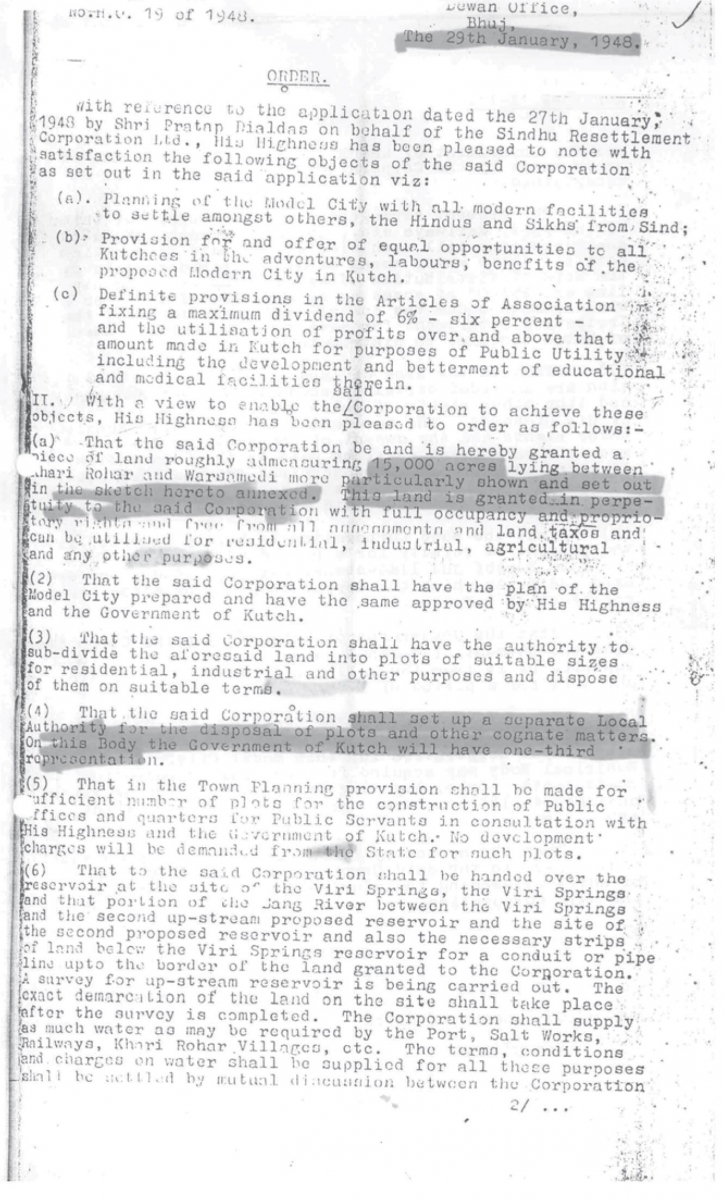

The Sindhu Resettlement Corporation (SRC) was incorporated as a joint stock company with the intention that it would function as a cooperative venture. J.B. Kripalani was appointed Chairman and Bhai Pratap was Managing Director, and the head office was in Bombay. Directors were honorary workers and not to benefit from the corporation. A limit was set to the distribution of dividends and the number of shares that an individual could purchase. With the commitment that SRC was not just for the resettlement of the Sindhi community but also for the development of Kachch, Bhawanji Arjan Khimji, younger brother of Maharao Vijayarajji, was taken on the board of directors. The Chandivali Cooperative Society was registered to provide housing. Formal agreements were exchanged: Bhai Pratap issued a letter dated January 27, 1948 requesting the grant of land and the Maharao’s office replied on January 29, 1948, graciously donating of 15,000 acres to SRC. The next fateful day, January 30, Bhai Pratap is said to have received a telegram from Gandhi giving his blessings for the foundation of the new town to be. Later that same day, Gandhi fell to an assassin’s bullet. On February 11, 1948, Bhai Pratap himself carried some of Gandhi’s ashes from Delhi where they were ceremoniously immersed in Kandla Creek by Acharya Kripalani, and a Gandhi Samadhi was built in Adipur (Gehani 2015). Ironically, the Maharao himself expired on February 26, 1948 (Gehani 2015).

Correspondence between Bhai Pratap and the government of Kachch

Images courtesy Nandu Asrani

Bhai Pratap had envisioned Gandhidham and Adipur to have self-sufficient districts with every amenity, and he saw to it that all development plans incorporated the scalability required for rapid expansion. However, the rapid expansion never occurred. Most of the Sindhis who needed urgent resettlement at the time, largely an urban elite, could not accept the idea of moving to a rustic, undeveloped area of India with few opportunities. Some opposed it to the extent of taking alternate delegations to Gandhi, asking for his help in carving out other parts of India more acceptable to them, even after Bhai Pratap had been promised the grant from Kachch and had started implementing his plans for it (Gehani 2015).

Bhai Pratap did not give up easily. He had built a house for himself in Gandhidham and spent much of his time there. The township came up, with not just schools and hospitals but other essentials such as printing press, ice factory and homes for the aged. Different neighbourhoods were built with housing for different income groups. But each one had care and thought behind it: temples and playgrounds; homes planted with fruit trees, back gardens to cultivate vegetables and sheds for people accustomed to keeping their own cow or buffalo. And Bhai Pratap made personal efforts to settle tradesmen and professionals necessary for daily life. A barber in Adipur today remembers his father’s story of how Bhai Pratap brought him to the town and told him to start work. When the barber said, ‘But where is my shop? I should at least have a barber’s chair!’ Bhai Pratap picked up four cement blocks and placed them one above the other. He then sat on the platform he had made and told the barber to go ahead and cut his hair. He brought cobblers, bakers and others too, and used their services himself to start them in business (Gehani 2015).

Luring a Sindhi population was harder, but Bhai Pratap worked at it and came up with ingenious schemes. These included sending well-known Sindhi poet-singers such as Master Chandur and Hundraj Dukhayal to relief camps to urge displaced Sindhis to come and settle in the new homeland he was building for them (Kothari 2007). He then kept an open house for needs and grievances of the new settlers and was committed to solving all the problems in his control.

As the township developed and people gradually came to live there, he was often seen sitting outside his house with his telescope as the sun fell, pointing out stars and constellations to his visitors. He gave talks on Egyptology (Gehani 2015). And, whenever there was a foursome, he never missed a chance for a hand or two of his favourite game, bridge (Tolani 2014).

The legal vortex

Who was responsible for the terrible things that went wrong for Bhai Pratap? It was a complex situation, with far too many factors to apportion blame to one or even just a few sources. However, the most consistent negative forces were the new laws and bureaucracy of the new government, and there were doubtless vested interests which exploited them.

They were certainly responsible for the first setback to Bhai Pratap’s homeland scheme and arose as an offshoot of the process of consolidating India into a republic. When India gained independence from the British, Britain handed over its territories to the new Indian government. However, there were 565 princely states not directly under the British, with their own hereditary rulers and identified as British ‘protectorates’. These were offered the option of joining either India or Pakistan—or of remaining independent. The process of accession of these states became extremely complicated. When it was discovered that a number of the erstwhile rulers had written over large parcels of land to their close relatives and favourite courtiers a short while before the accession, the Government of India declared their grants of land to be ‘null and void’.

The matter of the title of the 15,000 acres granted by the Maharao to SRC fell into a legal and bureaucratic maze which took years to unravel and what emerged was quite different to what had been intended. The grant of 15,000 acres was revoked and, in 1954, SRC was given a 99-year lease for 2600 acres. Further, SRC would be subordinate to various government bodies including the Kandla Port Authority and the Gandhidham Land Development Board (Gehani 2015).

More sinister problems arose out of India’s newly-closed economy. The new Indian government had a new charter for economic development. New business laws incorporating bans and quotas, seen today as illogical and regressive, were introduced. Businessmen, honed in an environment of natural response to supply-demand situations often found these laws impossible to understand or conform to. Many, despite a lifetime of strong traditions of scrupulous business honesty, suddenly found themselves branded as ‘cheats’ and ‘smugglers’.

When Bhai Pratap was arrested on the charge of misuse of imported goods, it appeared to be on a minor technicality. However, the case, first filed in 1960, dragged on. It was 1965 by the time he received his reprieve. Five years in prison had taken their toll and his health was failing. Towards the end of his internment he had been admitted in St. George’s Hospital, one of Bombay’s notorious municipal hospitals, but even there his family was only allowed to visit once every two weeks.

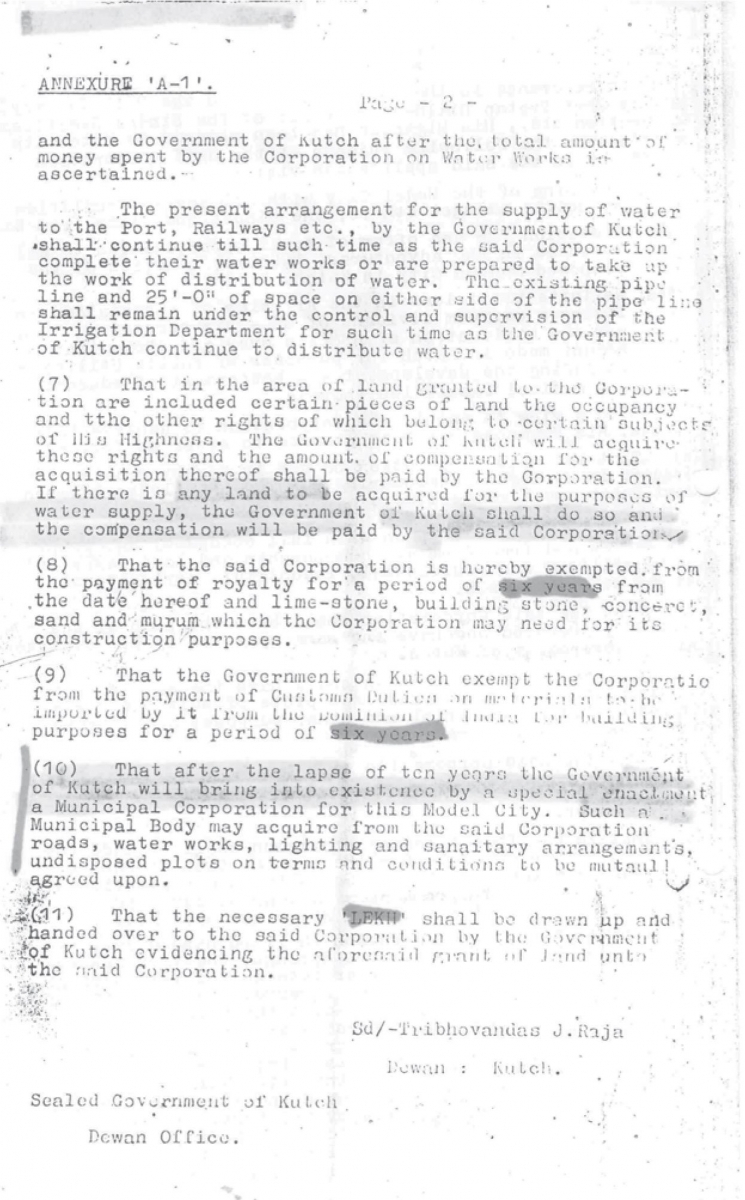

Bhai Pratap greets Nehru at the inauguration of Gandhidham. Nehru had enjoyed Bhai Pratap’s hospitality when he visited Sindh. His party had long taken Bhai Pratap’s generosity for granted. And yet, Nehru was at least partly responsible for the terrible travesty of justice Bhai Pratap suffered.

Photo courtesy Aruna Jagtiani

Bhai Pratap died in London on August 30, 1967. He was 59 years old. His body was brought to Bombay and from there to Adipur, where it was cremated in the Nat Mandir Compound. A samadhi was built at the spot, adjacent to the Gandhi Samadhi there.

The registered office of the trading firm M Dialdas & Sons stood, as it does today, at 190 Princess Street, Mumbai. Its business interests were scattered and diverse, and mostly dwindling, whether in Africa, Europe, the Canary Islands, South America, Hong Kong or the Far East. Many were closed down and their assets disposed of. The family’s Indian interests included a stud farm in Bangalore, the elite tailoring establishment M Das Tailors in Mumbai, a tea estate in Darjeeling and various others. There were also numerous real estate holdings, most significant of which is an enormous tract of land near Delhi which was under development at the time. Following a complaint of mismanagement to the Company Law Board at around the time of Bhai Pratap’s death, it was taken over by government-appointed directors who proceeded to fleece the company. Many believe that the case against Bhai Pratap was engineered by those who wanted to usurp his property. The litigation continues.

As for Kandla—today it hosts one of India’s major ports. In 1952 its foundation was laid by Jawaharlal Nehru, then Prime Minister of India, and it was designated a Major Port by Lal Bahadur Shastri, then Minister of Transport, in 1955. In 1965, it was given the status of India’s first Special Economic Zone, a culmination of Bhai Pratap’s vision, determination and tremendous hard work in converting a sheltered natural cove into a lucrative international facility instrumental in shaping India’s international marine presence. And yet, there is no acknowledgement or appreciation of Bhai Pratap’s contribution on any public document pertaining to Kandla Port.

Author’s note

I knew vaguely that my grandparents, Kishinchand and Devi Bijlani, had received generous help from someone called Bhai Pratap in getting settled in Bombay after Partition. But I assumed that this was a common story. After all, everyone knows that the wealthy Sindhis had gone out of their way to rehabilitate the underprivileged ones of their community.

When I started recording my mother’s stories of her childhood in Sindh, I began to realise that Bhai Pratap had been a substantial guiding influence to her family. But it was only after I began reading, writing and thinking more about Sindh and Sindhis that I understood what an extraordinary person Bhai Pratap had been. It was surprising to find no comprehensive source of information about him.

In the recent past, a few things happened which led me to put the pieces of the Bhai Pratap puzzle together and set the record straight. First, I read an excerpt from a recent biography of Ram Jethmalani, published by Penguin, in which Bhai Pratap is distastefully described as ‘an old Sindhi freedom fighter from the time of Independence, now a wealthy businessman.’ Even worse than the taint of recent and questionable business wealth, how could someone who died at 59 ever be described as ‘old’?

Second, a highly-publicised movie was released, which borrowed some facts and locale from an actual murder trial of the 1950s in which a naval officer shot his wife’s lover dead. It was a historic trial because the jury, influenced by tabloid-created public opinion, acquitted a murderer who had pleaded guilty. This trial and acquittal led to the jury system being abolished in India. While the judge in the case refused to accept the jury’s decision, the murderer was indeed released and further tabloid speculation led to this release being linked to Bhai Pratap’s release. In the public memory, a link was created between the release of a glamorous murderer and the honourable pardon of someone who had been suffered grave injustice, mistakenly accused and sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for an economic crime. This link glorified the glamorous murderer, and pushed Bhai Pratap and his contributions further into obscurity.

Then, in the course of interviewing someone, I happened to ask him if he knew of Bhai Pratap. This was a courteous, well-read, well-travelled, well-off gentleman; a Bhaiband himself but one who had served in the Indian armed forces. He replied, 'Oh, you mean the one who did that scam in Kandla?'

I put everything aside, collected all the information I could and here it is.

Bhai Pratap’s daughter Aruna Jagtiani and his grandsons helped me by sharing their memories. For help with accessing reference documents, sourcing images and various suggestions I am also grateful to Nandu Asrani, Nandita Bhavnani, Lal Bijlani, Thomas Chandy, Laxman Daryani, Mohan Gehani, Asha Idnani, Harish Jagtiani, Aslam Khwaja, Devendra Kodwani, Gul Metlo, Sekhar Seshan, Govardhan Sharma (Ghayal), Amrita Shodhan, Situ Savur, Mehtab Ali Shah, Dr N.P. Tolani.

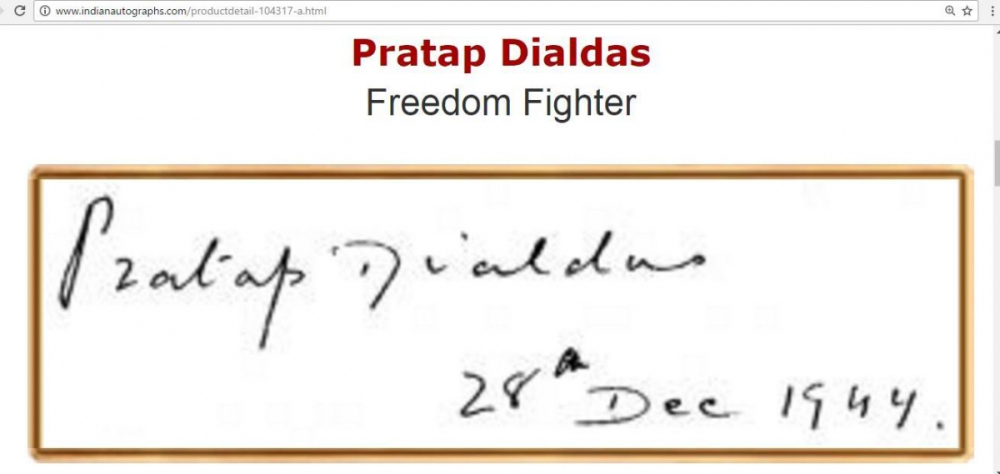

Bhai Pratap’s signature

Image source: http://www.indianautographs.com/productdetail-104317-a.html (viewed on November 27, 2016)

References

Advani, Bherumal Mahirchand. 1919. Sindh Je Hindun Jee Tareek. Hyderabad (Sindh).

Anand, Subhadra. 1996. National Integration of Sindhis. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House.

Aggarwal, Saaz. 2012. Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland. Pune: black-and-white fountain.

Bhavnani, Nandita. 2014. The Making of Exile: Sindhi Hindus and the Partition of India. New Delhi: Tranquebar.

Gehani, Mohan. 2015. Desert Land to Homeland. Adipur: Indian Institute of Sindhology.

Hiranandani, Popati. 1980. Sindhis the Scattered Treasure. New Delhi: Malaah.

Kothari, Rita. 2007. The Burden of Refuge. Hyderabad: Orient Longman.

Kripalani, J.B. 1970. Gandhi: His life and thought. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

Kripalani, S.K. 1993. Fifty Years with the British. Hyderabad: Orient Longman.

Markovits, Claude. 2000. The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947 Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Merani, H., & Van der Laan, H. 1979. ‘The Indian Traders in Sierra Leone’. African Affairs 78.311:240–50.

Nehru, Jawaharlal. 1958. A Bunch Of Old Letters. New York: Asia Publishing House.

Soundarapandian, Mookkiah. Development of Special Economic Zones in India: Policies and Issues 2012. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Tolani, Nandlal Pribhdas. 2014. Odyssey. Bombay.