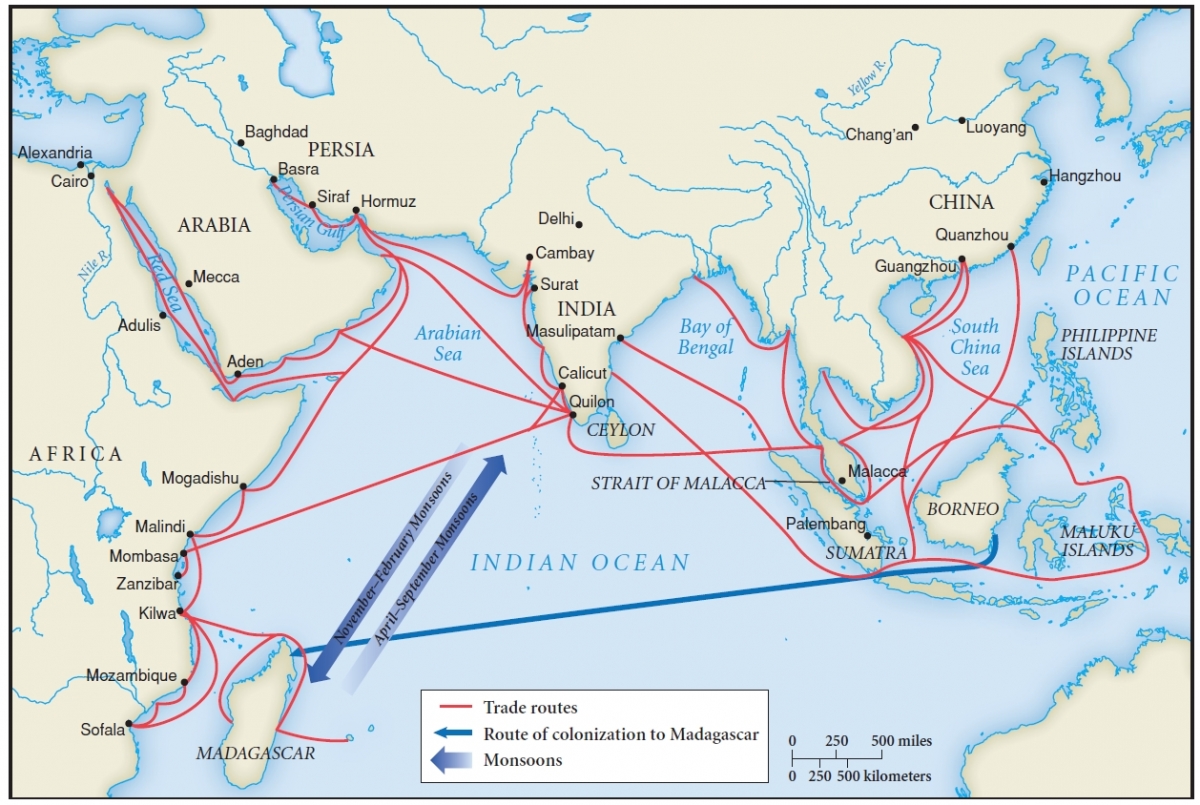

Indian Ocean trade routes. Credit: https://in.pinterest.com/pin/570901690240691434/ on November 27, 2016

Summary of the talk

India’s geography is such that it is a centre of trade both by land and by sea and this gives it a pivotal role in Asian trade.

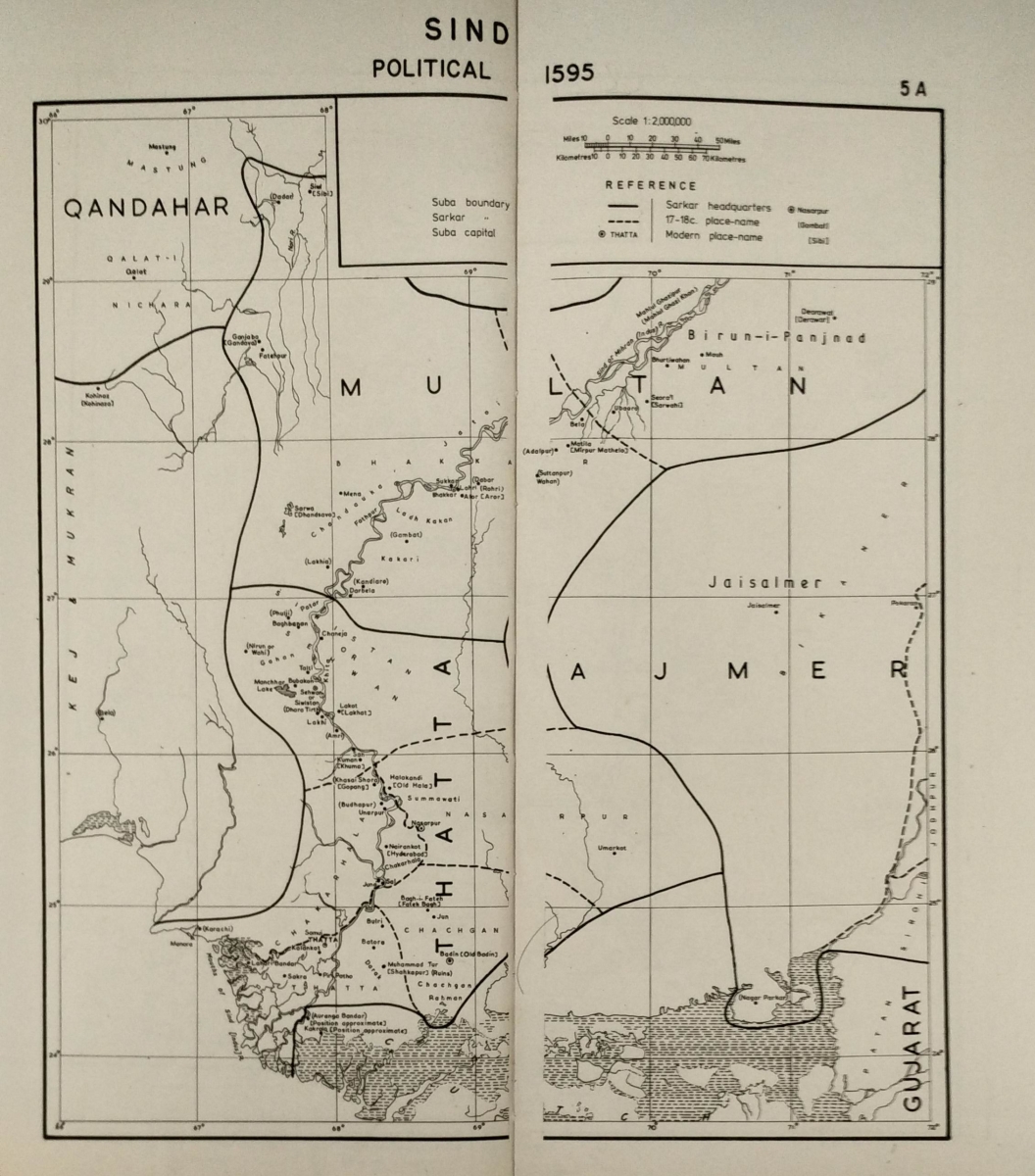

Three sections of India’s west coast are particularly well located to be part of both: the stretch from Karachi—the old ports of Thatta and Lahiri Bandar – up to Cambay; Rann of Kachch down till about Surat; and Goa down to the Malabar Coast. The Sindh-Cambay area has the double advantage of access to the sea. Going inland, the Bolan and the Khyber lead into Central Asia and the Silk Route. The land world is also linked to the entire hinterland of north India and to the products of the Deccan because the route from Cambay through Gujarat gives access to the Deccan also. Mesopotamia had products from the Deccan region, and they were sent via the Indus. In the early period the routes would have hugged the coast. By the medieval period, it was familiar territory and there would have no longer been a need to do so.

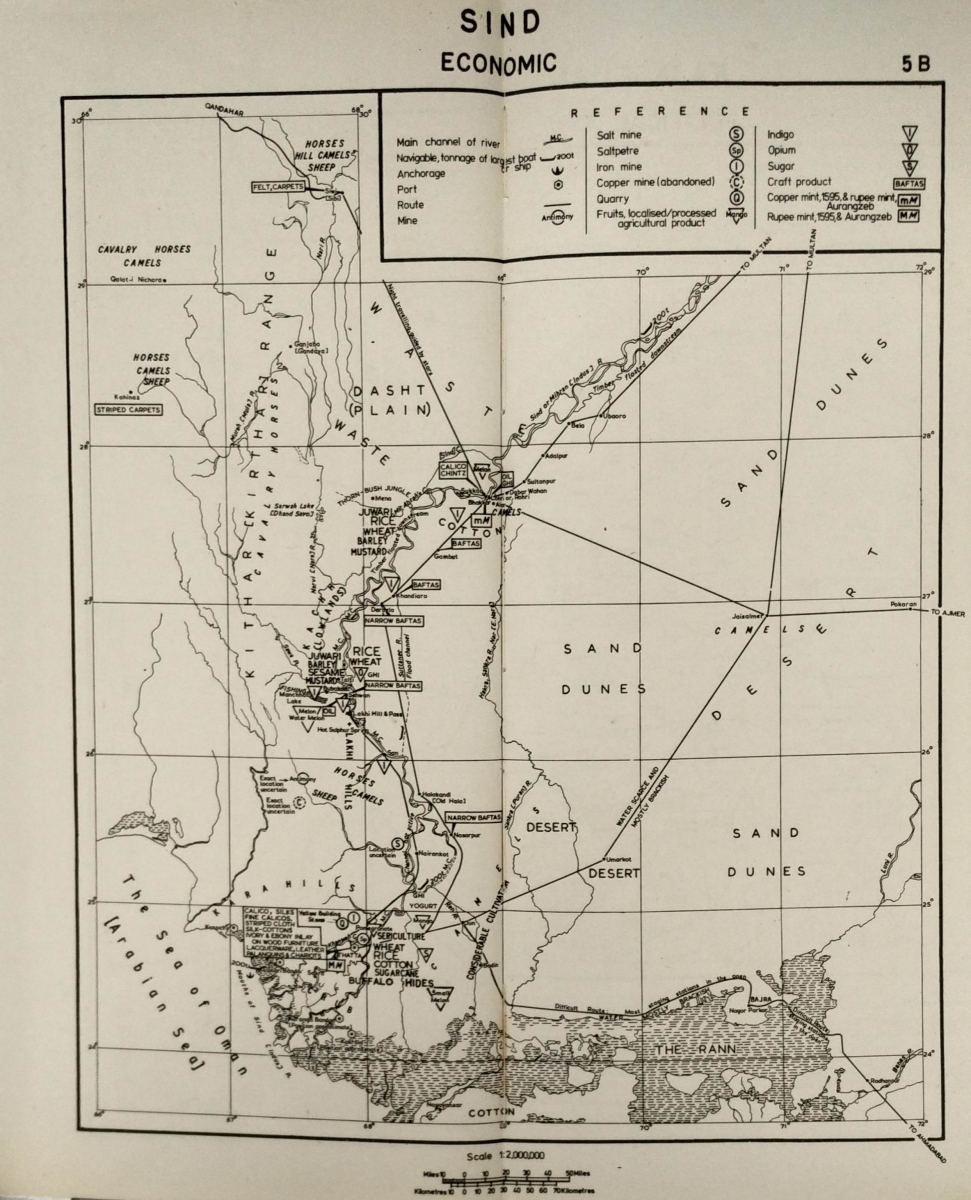

Sind Economic Map

Sind Political 1595 Map. Both maps have been reproduced here with kind permission of Irfan Habib © Irfan Habib. First appeared in An Atlas of the Mughal Empire. 1982. New York & New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

On the route of caravan trade, one side would lead from Karachi—Thatta, Lahiri Bandar—to Multan, Lahore, Kabul, Kandahar, Samarkand, Damascus. On the other side you could sail out from Lahiri Bandar to Bahrain, Muscat, Aden, Sofala, Malindi and around the Arabian Sea and back.

The Asian trading world of land and the sea is dominated by the wind, water and tides which influence trade. Before the age of steam, sailing was controlled by the wind. Depending on where you started, you knew where you would reach and how long it would take. There were sailing seasons and they depended on the monsoon winds. To cross the Arabian Sea, it was possible to sail hugging the coast and this was slower but could be done at any time of the year. The more productive method was to sail back and forth on the monsoon winds.

Besides the wind, there were also the currents. These could take you from Gujarat to Aden and back, despite or with the winds. A ship would leave Aden at Navroze and get to Surat 21 days later. If it did not reach in twenty-one days, it would be known that pirates had struck.

The tides were another factor: long-distance currents that brought the boat to the mouth of a river. With riverine navigation linking to ocean navigation, Sindh had an advantage. People living along the Indus would have had access to both and they would have had knowledge of both. They would have understood the problems of the Indus and how to navigate. From the mouth of the river they would know how to get into the sea, which too they would know how to navigate. Some Indus ports lay on the delta and they would have had the knowledge of delta navigation as well.

In terms of land, Sindh occupied a geographical space on the route from Central Asia into India and was always a part of the cross-cultural connections. The knowledge would have existed among the people of the region. They would have been a community, and there was a corpus of knowledge which they would have shared. They were at a central point of a manoeuvrable world and had the knowledge of how to navigate through it.

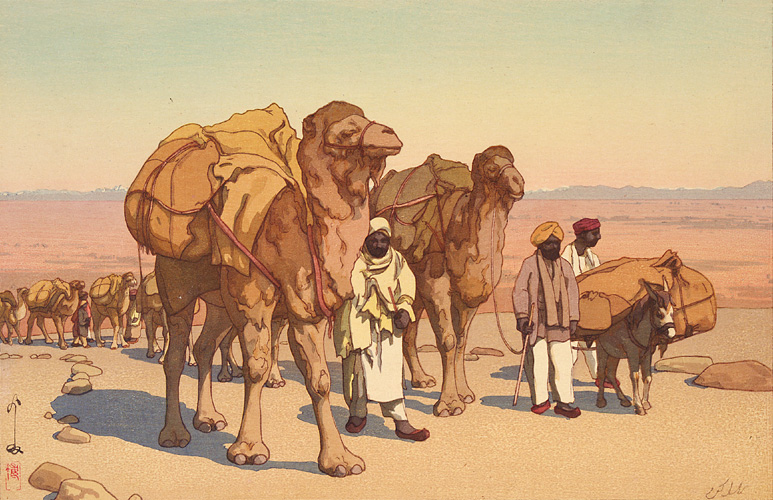

The two routes were comprehensive but they were also complementary. When there was snow in the mountains the passes were impassable so the caravans would not operate between say late October and March. But that happened to be the peak time for sea trade. And between say June and September, when the sea routes on the Arabian Sea close for the monsoon, the land routes worked best.

Caravan from Afghanistan: A Caravan of camels travels through a starlit desert night. The artist produced both a daytime and night time edition of this image. Woodblock print by Japanese artist Hiroshi Yoshida (September 19, 1876 – April 5, 1950). Image source: http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/zoom/S1996.26.jpg on November 27, 2016

And the trade would be linked to the entire production range of India. India has cotton; one important product is textiles, and every Indian trade community has dealt in textiles in some form. Different areas become noted for certain kinds of textiles, and the English factory records[i] indicate that the Sindh region had the not-quite-coarse, not-quite-fine cotton, what they called ‘patterned’ cloth which would have been the traditional block-printed cloth of Sindh. Cloth from other areas of India would have passed through Sindh: while Sindhi textiles probably went by the land route and the caravans into Damascus and beyond, Gujarat textiles probably took the sea route into Egypt and Malindi-Sofala-Ethiopia.

Prior to industrialization, cloth was both a domestic and a market-oriented industry. Weavers would often be part-time peasants. In parts of the country where land is marginal, income from both is essential. This was a community which had access to merchants. Cash exchanges would be at the market rates determined at the time of settlement. So they had money in circulation and they knew its value.

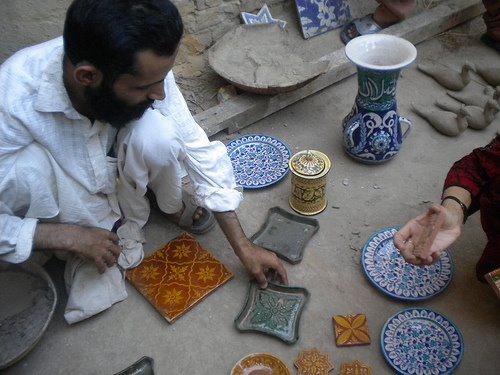

Besides weaving, there were other artisanal skills. The area was known for its bricks. This meant that they understood mud and this led to skill in pottery which would lead to tiles, ceramics and curios. There would have been an influence from the Chinese knowledge of ceramics, and the tile heritage of Iran and Central Asia, and all these filtered into Sindh.

Craftspeople in present-day Sindh in an ancestral occupation. Photographed by Syed Irfan Ali Shah Rizvi, September 2012

In that vast network there was also a vast range of products. The most prevalent were Arabian horses, Indian cotton and South East Asian spices. To these were added Chinese silk. There was also Damascene steel, the first steel, the material and the method of production, coming out of India. It is said that every major war across the known world was fought with swords of Indian steel. Besides these were all kinds of goods: there are references to the coral trade, bringing coral from the Armenian merchants in the Persian Gulf, who have brought the corals from Italy. In India, they exchange it in Delhi and Burhundpur for rubies from Burma, jade from Thailand, cornelians and agates from Cambay. And when pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, ginger come across the Spice Islands, they are often coming to the east coast of India, transported to the west coast, taken by land up to maybe Surat and then sent off from there. Part of these networks comprised groups of ethnic or geographically located people.

From about the 14th century onwards, probably earlier, there were the Banjaras, who did what was probably a year-wide circuit of India. They are small scale and long distance. They are small value but with lots of goods and therefore high value. There are descriptions of their caravans, of a thousand oxen travelling across the land. And they’re carrying wheat and rice; basically food. They start from Rajasthan and do a circuit of all of India and come back. And in the 13th century, they are taken out of Rajasthan and moved to the bank of the Yamuna by Alauddin Khilji to supply grain to the army.

Sindh is an important component of the Banjara trade, having trade networks across land and sea. This means having the knowledge of where to go with what; the knowledge of what will sell where; a sense of the fluctuation of markets and the understanding that tastes do not remain constant. That is possibly why diversification is a common feature of Sindhi businesses and in fact of most merchants on the west coast of India, arising from the need for variety, essential to retain a certain niche in their markets.

Much of the Asian trade is conducted through communities. The Hadrami merchants are from the Hadramout, south of Arabia. The Karimi merchants are probably from Turkey and beyond. The Armenians come. By the time we get to the Mughals, there is a group of Turkish merchants who are referred to as ‘Roomi’, because they are Byzantine, from the Eastern Roman Empire. And the Sindh region becomes a conduit in many ways. When the sea routes are unusable, still trade continues. Through the Khyber, the Bolan, you come to Multan and then go south into the core heartland of the Sindh region. These people, whether or not they were called Sindhis, would have been used to dealing with multiple groups. They would have established networks of connection at a subtle level. There may not be information about who the people were, but they were obviously people who were known, who had contacts and who were able to retain those contacts year after year after year. Sindh is the passage into India from Central Asia. It is the passage into India coming along the coast. From any direction, Sindh is a hub. And this has made the Sindhi community as the spokes of a wheel, that hub in its circuit of commerce gives Sindh the ability to move in multiple directions.

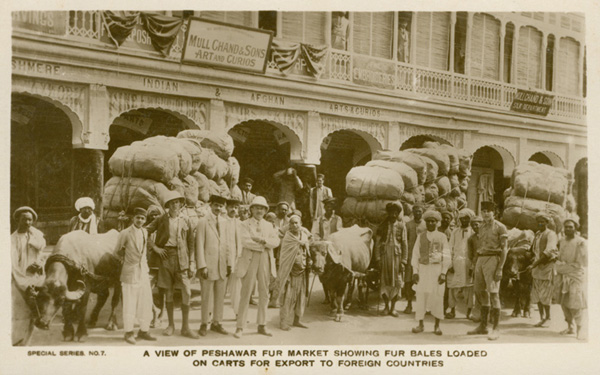

A group of British colonials and ‘natives’ pose for this photo, showing carts loaded with fur for export from Peshawar to other countries. Blending into the background and barely noticed, somewhat like the Sindhis in global trade, the board of merchants Mull Chand & Sons, Art and Curios, can be seen. Source: Collection of Omar Khan, harappa.com. Downloaded from http://www.gutenberg-e.org/hanifi/images/fullsize/peshawar-market.jpg on November 27, 2016

This ability became honed when Sindh was integrated into the British Empire in 1843 and subsequently included in the Bombay Presidency. Sindh was crucial to the British operations in Central Asia with the Afghan wars and beyond, as part of the network into Egypt. As part of Bombay Presidency and with the roads and railroad, it was better connected to the rest of India. So Sindh acquired a centrality which perhaps was not so obvious earlier. While the Sindhis now have freer access to other parts of India and within the construct of the British Empire, they carved a niche for themselves. The Parsis dominated trade in the Bombay area and similarly there were areas controlled and monopolised by the British. Starting with small-scale and long-distance, the distances can become longer as they go within the empire. The opening of the Suez is perhaps the crucial point at which the Sindhi diaspora can go beyond the confines of Asia into the Straits, West Africa and beyond. While the diaspora may be facilitated by the British Empire, it is rooted in their previously developed ability to navigate through multiple areas of trade and this skill allows them to manoeuver and make profit even within the monopolistic empire controlled by the British.

It’s also interesting that the Sindhis remained invisible. In the early days they contributed silent but crucial components to the networks of commerce; like the region itself they facilitated the movement of goods and were part of it but remained unnoticed.

After Partition, Sindhis lost Sindh. Sindh as a region of identity is no longer part of Indian Sindh. In terms of identity, they are Sindhi but no longer of Sindh. They are Indian; part of the Indian community; part of the Indian diaspora; but also have an identity and a legitimacy which is as much with that lost homeland as it is with their present location. Tracing the historical trajectory of their movement is difficult without considering the notion of a community beyond borders.

Full transcript

Sindh as a crucible of products and its location as a springboard for trade.

The first thing to understand is that India is the centre point of a whole lot of trade and that trade is both by land and by sea. You can’t have country which has so much geography and not have both. And there are 3 regions of India which are actually geographically very well located to be part of both. One is the stretch from Karachi: Thatta, Lahiri Bandar, the old ports, up to Cambay. That’s one area. The other is Rann of Kachch down till about Surat, and the third is Goa down to the Malabar coast. Those three are crucially located for the westward trade. You have the same thing for the east coast also.

The Sindh-Cambay area has the double advantage, that from Thatta, the old port of Lahiri Bandar, the modern port of Karachi, you get access to the sea. And if you go inland, you can get to the Bolan and the Khyber and into Central Asia and the Silk Route. So that becomes your transition route. It gives you access to both, the land world and the sea world. And the land world is also linked to the entire hinterland of north India and to the products of the Deccan. Because if you can get as far as Cambay, then through Gujarat you have access to the Deccan also.

We do know that Mesopotamia had products which were from the Deccan region. And that they were sent via the Indus. The routes probably hugged the coast. By the time you get to the medieval period, there was no longer a need to hug the coast because they knew the way traffic moves.

So one part is the sea trade in and out, and the other is the caravan route, and all of it links to trade: Karachi, Thatta, Lahiri Bandar, Multan, Lahore, Kabul Kandahar, Samarkand, Damascus. That’s one area. The other would be Lahiri Bandar, Bahrain, Muscat, Aden, Sofala, Malindi and around the Arabian Sea and back. So there are networks of geographical connection and economic connection. That’s where you have to locate the Asian world. To that is linked the entire production range of India. India traditionally has been textiles. There is no Indian trade community that has not dealt into textiles in some form, and that is because India has cotton. Different areas become noted for certain kinds of textiles. There are the English factory records which talk about the Sindh region being the area for not quite coarse, not quite fine cotton, an in-between kind of cotton textile and they call it the ‘patterned’ cloth. What the pattern was, how much was patterned, is not clear. They called it patterned cloth and going by the logic of English factory records, when they said patterned cloth they probably meant block printed. They clearly distinguished between patterned and painted, and the patterned was block printed.

Again, traditionally, prior to industrialization, cloth is both a domestic and a market-oriented industry. Very often you would have weavers who were also part time peasants. You don’t have full-time weaving and you don’t have full-time farming activity. You do both. And in parts of the country where land is often marginal, you cannot do one single activity, you need the income from both. So if you are doing weaving and farming both, you have access to merchants. Because, and particularly with the Mughals, all revenue would have to be paid in cash. And the cash would be according to the market rates determined at the time of settlement. So the people would be aware of market rates, and they would have money. You would have money in circulation, and you would know the value of money. There were weavers and there were also artisans. This area is also known for its bricks and the brick-making industry has traditionally been an important one in that area. And if you know bricks, you know mud. And if you know mud, you have to know pottery. So you’ve got your range of the Sindhi craft. And if you’re talking about tiles, you would have some kind of ceramics and this would lead you into curios. Curios were very often China and linked to the Chinese knowledge of ceramics, and tiles are also linked to Iran and Central Asia. So all of that is filtering down somewhere in Sindh.

How wind, water and tide influenced trade, and worked together to make Sindh a major conduit

The trading world of Asia is dominated by the land and the sea. The sea has wind, water, tides. So depending on where you start off, you know where you’re going to reach. And the monsoon is the main part of the wind and there were sailing seasons. Before the age of steam, sailing was of course controlled by the wind. So, going around the Arabian Sea, there were two options. One was to hug the coast, which could not be done during the monsoon but could be done at any other time of the year, irrespective of the size of the boat or the winds that existed. The other was of course to take advantage of the winds to sail across back and forth.

The wind was one part of it but there were also the currents. These could take you from Gujarat to Aden and back again. And that can be despite or with the winds. There’s a document which says that ships leave Aden at the time of Navroze and they get to Surat twenty-one days later. There are also a whole lot of references which mention the problem of pirates, such as the statement that we know the ship left on a particular day and they have not arrived twenty-one days later so they must have encountered pirates.

Then there are the tides. The tides are again twofold. One are the long-distance tides, the currents that take you across. And the other are the currents that get you, maybe into the mouth of a river. The riverine navigation has to link to the ocean navigation as well, and that’s where I think the Sindhis would have had an advantage. Living along the Indus River, they would have had access to both riverine as well as sea going navigation, and they would have had knowledge of that navigation. Therefore, they would have understood the problems of the Indus and how to navigate through them. And then, once you get to the mouth of the river, they would know how to get into the sea and to navigate that as well. By and large our ports are all riverine ports which means they are not all on the coast, they are all a little up the river. And on the Indus you’ve got the delta, so the ports are on the delta. Delta navigation requires a different knowledge. Clearly, all of this is knowledge was already there in Sindh. Beyond this is the network of connection which gives you land and sea. Or land and water, not just sea.

Land is hinterland, as well as what one person has called the cross-cultural connections. He says that any part of Asia, you cannot see as a single unit. You have to be able to map the cross-cultural connections[ii] across that region. And the Sindhis are part of that cross cultural connection. They occupy a space geographical space which is on the route from land to land, from Central Asia into India. Then from sea to land it is the ports of Thatta, Lahiri Bandar, later Karachi, sea to land, what has been called the foreland. And there is also the fluvial world of the delta itself. So the Sindhis are located in this network of fluvial, alluvial, peasant and sea. And that is perhaps their greatest strength. This is knowledge which would have existed among the people of the region, irrespective of whether the people could or were identified by name or not. They would have been a community, there would have been a corpus of knowledge which they would have shared. And that corpus would have stood them in good stead in later years. So they work in a world which is in many ways on the margins but in the centre. Bordered but without borders, so they’re in a very manoeuvrable world. And to be able to navigate through all of this was probably their greatest strength.

The complementing land and sea connections in the routes of Asia and an idea of their utility; Sindh as the crossroads and the understanding of markets; a glimpse into traditional products of the Indian region

Because we are talking about the pivotal role of India in Asian trade. That pivotal role is necessarily as I said, sea and land. Now the land connections take you into Central Asia, through Central Asia into the Caspian Sea area and into the Black Sea area. And on the other side, into the China region. Now that is the China part, I don’t think Indians ever got into China. But Buddhism did get in. Now Buddhism took the sea route. So Buddhism goes via the Bay of Bengal, around, into South East Asia, around the South China Sea, and enters from the other coast of China. But when the Chinese pilgrims come, they take the land route and come. So you’ve got a full circle happening there.

We could think of Asia as three intersecting circles. One circle is the east coast of Africa to the west coast of India, extending to the centre of India. The second circle is the west coast of India to across the Bay of Bengal. Third is from the east coast of India across into China. In all those three you’ve got the intersection of land and sea. And that is the crucial part. Because there is the sea but the sea is meaningless without access to the products of the land. And the products of the land are regionwise but they’re also distributed around the entire region. So if for instance Sindh is textiles, so is Gujarat. But Sindh textiles probably went by the land route and the caravans into Damascus and beyond while the Gujarat textiles probably take the sea route and get into Egypt and Malindi Sofala Ethiopia. So you’ve got a bifurcation. Which does not mean that the traders were bifurcated. It means that the trade routes were bifurcated, and the trade routes would be therefore, caravan, cart and boat. So your caravan routes would have to take both routes are dependent on physical and climate conditions. So the caravan routes would obviously have to take note of when there’s snow in the hills, making the passes impassable. The caravan routes are not operative between say late October and March. But that is your peak time for sea trade. When one is closed, the other opens up. And between say June and September, when the sea routes on the Arabian sea are not working, that’s when the land routes are working. You cannot talk of them as two separate module; they are complementary to each other. And they all deal in a variety of items. To this is added actually the entire internal network of India. Which from about the 14th century onwards at least, probably earlier, we have a group who was called the banjaras. They do what is probably a year-wide circuit of India. So they are both, small scale, long distance. They are small value but lots of goods and therefore high value. You’ve got their caravans. We have descriptions of their caravans of a thousand oxen going across.[iii] And they’re carrying wheat and rice; basically food. But they are starting from Rajasthan and doing a circuit of all of India and coming back. And in the 14th century, in the 13th century, they are taken away from Rajasthan and dumped on the bank of the Yamuna by Alauddin Khilji and told, you supply the army first. Because they are grain merchants. Now somewhere, Sindh is part of this. For one, Sindh is part of the network of trade, land and sea. For another, it is not quite on the fringes, but not quite in the centre of the Banjara trade as well. So they are part of that network of internal connections and the network of the long distance connections as well. And in this network there would be again two major dimensions. One is knowledge of where to go with what. And therefore knowledge of the markets. And what will sell where. Also that would require a sense of the fluctuation of the market. That tastes do not remain constant. So you would have to go into multiple areas to be able to retain a certain niche in that market. That is possibly where the Sindhis go into that diversification that you find as a common feature. Because by and large you would find most of the merchants on the west coast actually across of India, they never concentrate on a single thing. Cloth is a constant. But there would be times when we have references to the coral trade. And the coral trade is something where they go to the Persian Gulf and they get the coral from Italy from the Armenian merchants. And that is coming into India. And in India they are exchanging it in Delhi, in Burhanpur, they are exchanging it for the rubies of Burma. So you’ve got mention of the rubies from Burma, the jade from Thailand, the coral from the Mediterranean Sea and then you’ve got the cornelians and the agates of Cambay. All of this is also wandering around. And then there is pepper. There is pepper, there is ginger, there is all kinds of spices. And then there is the damascene steel. The steel which is the iron of India which is made through a process which is, well it’s heated, it’s not quite steel and it’s not quite iron but it’s called steel. Because of the way it is made you get these waving lines in it like water running. And it’s I don’t remember who said it but somebody said, every major war across the world known world was fought with Indian swords. So the steel of India, the iron of India, the method of production of that iron and steel, all of that is there. In fact the entire network of Asia is based on three major items: Arabian horses, Indian cotton and South East Asian spices. Into this as an additional item comes Chinese silk. These make the world go round. And all of these are traded across the known world. India is believed to be the source of pepper. When the Portuguese come here, it takes them another ten years to discover that Indian pepper is not just Indian pepper it’s also Indonesian pepper, it’s also the spices of the lands beyond India. So they come to be called the Spice Islands. All of this is finding its way across. And when pepper, cardamom, cinnamon, come across the spice islands, they are very often coming to the east coast of India, transported to the west coast, taken by land up to maybe Surat and then sent off from there. So you’ve got, like I said, networks. Part of this networks is definitely groups of ethnic or geographically located people.

Community networks of trade in the region; Sindh as a hub and the historical reasons which give Sindhi traders the ability to move swiftly in different directions. Also: some reasons why Sindhis, despite their omnipresence have remained unseen

This entire trade of Asia has any number of people in it. We have mention of the Hadrami merchants who are from the Hadramout, south of Arabia. The Karimi merchants who are probably from Turkey and beyond. We’ve got the Armenians coming in. By the time we get to the Mughals, there is this strange term where a group of Turkish merchants is called ‘Roomi’. Roomi apparently comes from Room, because they are Byzantium, which is the Eastern Roman empire, so they become Roomi. And they are all moving around Asia. If you talk about Trafalgar Square and the traffic, Asia at that time must have been like that, a crossroads! All across the country. Again, here is where the Sindh regions becomes a conduit in a whole lot of ways. Because when you cannot use the sea route, trade continues. Over land is where Khyber, Bolan takes you down, yes to Multan, but also south of Multan. Into the core heartland of the Sindh region. These would have been people who were there, whether or not they were called Sindhis. These were people who would have been used to dealing with multiple groups. Who would have established their networks of connection at a very subtle, maybe even subterranean level. Meaning that you don’t have information about who the people were, but it’s not completely blank. There were people there and they were obviously people who were known, who had contacts and who were able to retain those contacts year after year after year. So Sindh is your passage into India when you’re coming across from Central Asia. It is your passage into India when you’re coming along the coast. From any direction, Sindh is a hub. And if you think of the Sindhi community as the spokes of the wheel, then that hub and that circuit of commerce, gives you Sindh as the hub and the ability to move in multiple directions.

Now that ability to move becomes honed when Sindh is integrated into the British empire. Because, with 1843, when Sindh is included into the Bombay presidency, then Sindh become crucial to the British operations in Central Asia, the Afghan wars and beyond, it’s Central Asia as well. And it’s also part of that network into Egypt. It is also part of Bombay Presidency so connected to the rest of India. So Sindh acquires a centrality which perhaps was not so obvious earlier. As the presidency and then roads and railroads even more. So Sindh It acquires a prominence and the people of that province, the Sindhis, get a greater ability to move within the construct of the British empire. So when they are moving, they are moving in directions which perhaps they couldn’t have gone. The Parsis were in any case dominating the Bombay area. So they are moving into areas which are not controlled or monopolised by the Parsis and the private trade of the English. Therefore they are moving into again perhaps historically, small scale long distance. So the distances become longer because they can now go within the empire. And the Suez then becomes, the opening of the Suez is perhaps the crucial point at which the Sindhi diaspora can go beyond the confines of the Asia into wherever else they want. The Straits, West Africa, all of it. So you get the diaspora being created through the British. And this diaspora is routed I would think in their ability to the earlier, their ability to navigate through multiple areas of trade. Given that the empire is monopolistic, the empire is controlled by the British, the ability to be able to manoeuvre and to make a profit wherever and however one can would have been crucial. So the Sindhis, if they go into business, it is business of multiple kinds, but they’re not the business kinds of the Parsi variety. It may not be entrepreneurship and industry but it is definitely business. And that business and the ability to see avenues for business would I think would be historically located. Because of the knowledge of the reason and the network, the networked communities, becomes relevant to them. And so the Sindhi region is never invisible. The people of Sindh are invisible probably because they are involved at a level which need not be documented. Without that level existing, you could not have had the networks of commerce. So they are part of the networks but they are the silent part of the networks. Because they are like the region itself, they would be the conduit. They would allow the movement of goods, they would be part of the movement of goods. But they acquire visibility only after the British becoming integrated into the British Empire. Until then they are the silent community of the region.

And then post Partition, the homeland is lost. So Sindh has a region of identity is not part of the Indian Sindh any longer. Which means, how do you identify them? They are not Sindhi but they are Sindhi. They are Indian, they are part of the Indian community, they part of the Indian diaspora but they also have an identity and a legitimacy which is as much with that lost homeland as it is with their work over here. So historically tracing the trajectory of the movement is going to be very difficult for anybody who does not get into the entire notion of the community beyond borders. That’s what Sindh is all about. The community exists, the borders are there, but borders have always existed. So what is the Sindhi community as a community of people who can work , who can get into a variety of activities and who are then part of India. How much Partition has changed their notion of themselves is something that I will not comment on.

References

The references are from the English Factory Records, both the Foster series, and the original unpublished records, available in the Bombay and Madras Archives, and of course in the India Office collections.

http://asianhistory.about.com/od/indiansubcontinent/ss/Indian-Ocean-Trade-Routes.htm

South Asian Economy During 16th to 18th Centuries and the Great Divergence Debate by Najaf Haider https://www.academia.edu/1567443/South_Asian_Economy_During_16th-18th_Centuries_and_the_Great_Divergence_Debate

Forms of money and its availability in Mughal India by Rabindra Kumar Sinha http://ijmsrr.com/downloads/1202201634.pdf

[i] The references to Sindh cloth and trade are to be found, most easily, in the series called 'The English Factories in India', edited by William Foster. It was published by the Clarendon Press, Oxford, between 1907 and 1921, and there are 13 volumes, plus four more, called the 'New Series', edited by Charles Fawcett.

[ii] 'Cross-cultural connections' is a term used by Philip Curtin in Cross-Cultural trade in World History Cambridge University Press, 1984.

[iii] One of the best descriptions is from Peter Mundy, an early 17th-century employee of the English East India Company, who travelled for his work across north India, mainly Surat to Aara to Patna and back. There is also an article by Irfan Habib to do with Banias and Banjaras, published in a book edited by James Tracy.

References

Curtin, Philip. 1984. Cross-Cultural trade in World History Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Foster, William. 1907–21. The English Factories in India 1618–1621 to 1668–1669: A Calendar of Documents in the India Office, British Museum and Public Record Office. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Habib, Irfan. 1990. ‘Merchant Communities in Pre-Colonial India’, in The Rise of Merchant Empires: Long-distance Trade in the Early Modern World, 1350–1750, ed. James Tracy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp.371–99.