Power and Hindu minorities

How powerful were Hindu minorities in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh? This is a rather complicated question, so what I’m going to do here is take it in three different pieces. First let me address the Hindu part, then I’ll address the minority part and then I’ll deal with the power issue.

There is a general tendency in the historiography of South Asia, starting in around the second half of the 19th century, to talk about the social geography and environment of India as being divided between Hindus and Muslims.

Now this is a trend that started earlier. It can be traced back maybe to the 18th century. But it became much more intensely felt in India in the latter part of the 19th century. You just have to look at the work of Sandra Freitag or Gyanendra Pandey in order to illustrate this fact.[i] This tendency moved on through the 20th century. You see a communalisation of history and identity in Sindh; intensely so in the course of the first half of the 20th century, ultimately culminating in Partition.

A lot of Sindhis, a group I like to call the Diaspora Sindhis, left Sindh after Partition and have increasingly identified themselves as ‘Hindu Sindhis’. One of the difficulties of this particular identification of these groups as ‘Hindu’ Sindhis really has to do with the religious genealogy and history and sociocultural practices of these communities.

As most Sindhis will be able to tell you, their religious practices tend to include and sometimes focus on the Guru Granth Sahib. This is really important, because it points back to a history that traces many of these Hindu Sindhis or Diaspora Sindhis back to the Punjab.[ii] So a lot of these groups are not particularly orthodox Hindus in the traditional sense. In fact, they have a genealogy that points back to Sikhism. A lot of them are in fact historically what we call Nanak Panthis or followers of Guru Nanak; that is, non-Khalsa Sikhs.

Now this history is particularly important, because it points towards the origin stories of many Diaspora Sindhis or ‘Hindu Sindhis’. Many of the communities that were forced to flee during and after Partition, or the individuals who were forced to flee during and after Partition, have genealogies that take them back not to Mohenjodaro or even into medieval Sindh, but rather to the Punjab and the twilight of the Mughal empire there.

In the Punjab we had a situation in the 18th century with the demise of the Mughal empire state. And we see the rise of the Jats and under the banner of the Khalsa. What we have going on in this part of India during the 18th century is in fact increasing violence: increasing violence that actually pits different kinds of Sikh communities against each other. So it was Mughal imperial policy during this particular period to particularly promote non-Khalsa, non-Jat groups, specifically the Khatri. The Khatri were largely urban, administrative castes. If you see the look at the violence in the Punjab in the 18th or the 19th centuries, with the disintegration of the Mughal Empire and the rise of the Sikh states, what you observe is a lot of urban-rural violence which invariably involves Jat and Khatri violence also.

During this time period, the Punjab is becoming an increasingly hostile place for urban as well as administrative groups associated or attached to the Mughal imperial structure. We have at the same time, the Mughal imperial structure having already dissolved to the south of the Punjab in Sindh and the development in the opening up of successor states in this particular time period. The violence in the Punjab during the 18th century, with the establishment of the Khalsa and the other Sikh states dominated by Jats, and given the trading as well as government opportunities in more stable regions to the south of the Punjab, in Sindh, was an incredible draw for certain caste groups, particulary Khatris who, in fact, migrated from the Punjab into Sindh during the 18th century.

A lot of these particular groups were then subsequently integrated into local regional categories in Sindh, particularly amongst the Lohana group. Now the Lohanas were a category that can be traced back through the medieval period but one that had been depopulated as Lohanas converted to Islam and other faiths.

The Lohana are traditionally associated with mercantile and merchant groups. The groups coming into the Punjab from the north were integrated into the Lohana social category and as a result found themselves integrated into a sort of grab-bag category with a lot of other individuals.

What this means is that as a result of this particular set of migrations [from the Punjab], which were particularly noticeable/intense in the 18th century, is that a lot of individuals who identify now as ‘Hindu Sindhis’ have genealogies which trace back to it. And a lot of them are, in fact, as I said before, ‘Nanak Panthis’ and they are not strictly speaking orthodox Hindus. This is why you also see a variety of religious practices amongst Sindhis, many of whom have genealogies which trace back to the Sikhs. As I mentioned before, the Guru Granth Sahib is particularly important in many Hindu Sindhi temples and also ‘Punjabi’ is not an uncommon name among Hindu Sindhis.[iii]

It is a bit of a misnomer to identify these groups as ‘Hindu Sindhis’ in the context of the colonial and pre-colonial period. It’s a much more appropriate term to use for the post-Partition period. However, as you shift back in time, as happens with many social categories, it becomes more difficult to maintain the identity over time.

Now, considering the power of Hindu minorities in colonial and precolonial Sindh, the question of these minority groups, whether you call them ‘Nanak Panthis’ or whether or not you identify them as Hindus, is in fact a very complicated question too. If you look at the entirety of Sindh, these groups, whether you call them Hindus or Nanak Panthis or Lohanas, were minorities. But they are only minorities when you consider the population as a whole. If you disaggregate the population between urban and rural, you see a slightly different story. The Hindu groups or Nanak Panthis or Lohanas—or non-Muslims, which is probably a better way to put it—were always a minority in the rural sectors of Sindh. However, if we follow the work of Alan Jones, this was not always the case in the urban centres of India.[iv] In fact there are a number of situations where the non-Muslim groups occupied the majority of the population in the urban centres. And this is the reason why many of these particular groups had very powerful positions within the urban centres of Sindh. They occupied and controlled, for instance, the institutions of social and political importance in Sindh’s urban centres. They also occupied the economic positions of power as mediators of the rural economy with the wider world.[v] So to talk about Hindus as being a minority in Sindh may be true in one sense. But if you look at it more deeply what you end up finding is a more complicated story which actually tells different stories based on whether you are discussing rural Sindh or urban Sindh or whether you’re talking about the entire population of the region.

In addition to the complications, going to the question of whether or not the Hindu minorities of Sindh had power in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh, one has to address the issue of power. I glossed over it quickly, with reference to the urban influence, or the influence of non-Muslims in urban Sindh/in the colonial and pre-colonial period.

It is definitely the case that non-Muslims, be they Lohana or be they Nanak Panthis or Hindus, in pre-colonial and colonial Sindh were far from powerless. It is often the case, if you look at the literature in the 19th century, particularly the British literature in the 19th century, that these minority groups were marked as oppressed minorities in Sindh. This was used ideologically by the colonial state in order to justify the annexation of Sindh in the 1840s. If you actually get into the sources, the local and the religious sources that are available in different parts of the world, you find that the story about the oppressed minority Hindu in Sindh is a little more complicated. And the plain fact of the matter is that, in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh, and at least starting in the 18th centuries, ‘Hindu’ groups (for example Amils and Bhaibands), who are, in fact, subgroups of the Lohana, occupied particularly important positions of power in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh. Amils had a monopoly on the power of the state and in pre-colonial SIndh they were the state administrators of the Amirs’ state. They were in fact, as I say in my book, ‘the officers of despotism’ rather than the Amirs themselves.[vi]

The Bhaiband, in contrast, had a monopoly on the power of capital in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh.[vii] So these particular powerful minority groups, who would today identify themselves as being ‘Hindu’, were far from powerless. They controlled two really important elements of power in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh, both the political power, that is of the state, through the administration and through the Amils; and the power of capital, the power of money, through Bhaibands. So I would make the argument that ‘Hindu’ minorities in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh were nowhere near as powerless or in need of saving by the colonial state, thereby requiring the annexation of Sindh in the 1840s, as the colonial sources make them out to be.

Spectrum of business

What was the spectrum of business that Hindu Sindhis or non-Muslim Sindhis were involved in? I would address this in a couple of ways. Let me look at the precolonial story because that’s what I know best from my own research. And then let me gloss a little bit and look towards the colonial era to answer that.

What did these groups deal in? Where was it coming from? To whom did they sell? Well, during the pre-colonial period, before the 1840s, it is very difficult to tell exactly. And one of the reasons for this is the nature of the kinds of source materials that we have dating before the mid-19th century. In the 1850s, the British decided that the Persian source of government records in Sindh were of no use to them and destroyed them. A lot of what we have in terms of information about commodities, trade and these sorts of things were all filtered through the East India Company archive and the priorities of the East India Company and its various officers at this given time. So a lot of what we know about this period and the pre-colonial period is a little speculative.

But what I can say is this. Most of the business practices engaged in by various Bhaiband or various Hindu traders were all attached to the agrarian economy in Sindh. During this period and a lot of periods the agrarian economy in South Asia is particularly important. South Asia is still largely agrarian in nature. And the place where sovereigns were able to extract the most wealth, in terms of taxes, was always from agrarian production. So a lot of the trade and economy in Sindh and in South Asia in the 19th century and before, for many centuries previous to this, was all tied up with issues of agrarian production. So we do know in fact that Hindu merchant traders or Bhaibands were deeply involved in the grain markets and in the moving around of grain and the purchasing of grain and the selling of grain. We also know that a lot of them were involved in the financing side of things. So there is a large range of activity, going all the way from the small grain merchants to the large business houses that had diversified business interests, including financing for various different projects. But a lot of this financing and a lot of the activity that these Hindu merchants were, in fact, involved in were rotated around the agrarian economy in Sindh in some way or another, and this is consistent with the social experience in South Asia, in general, during this particular time period.

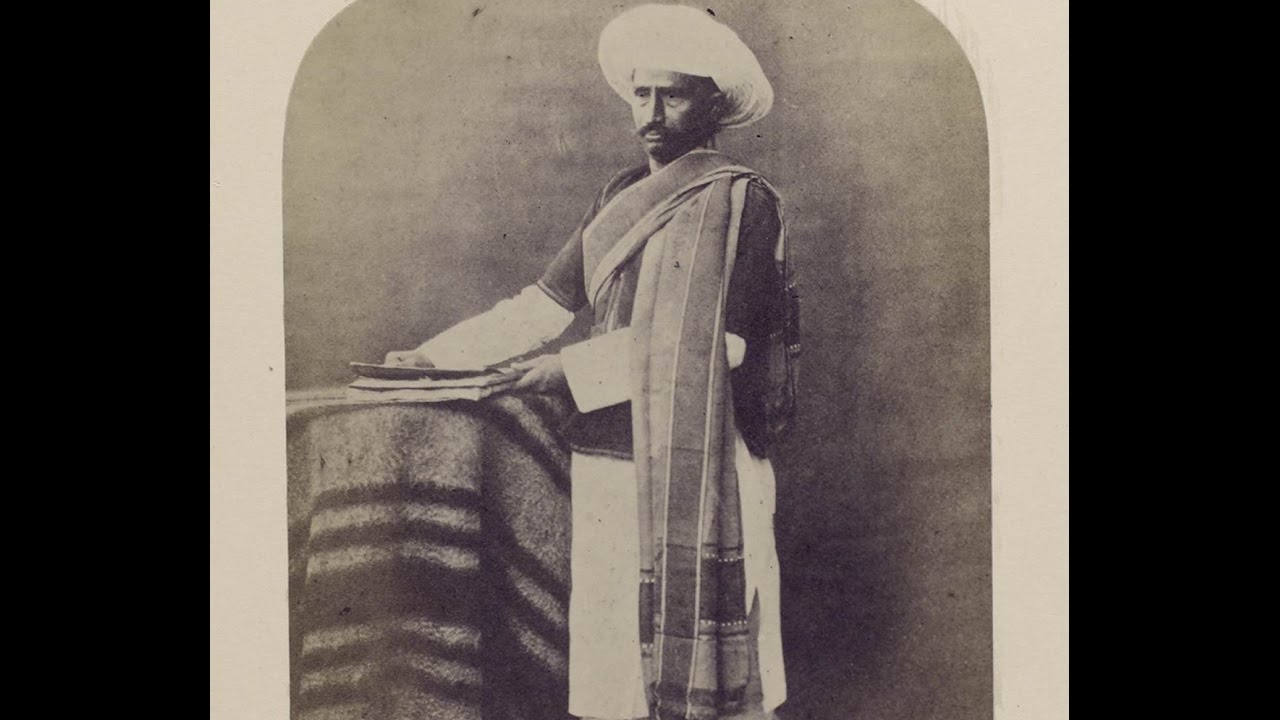

Naomul Traitor

Was the Hindu merchant Naomul Hotchand a traitor? In order to answer this particular question you need to ask another question and that is, a traitor to what?

Was Naomul a traitor to Pakistan? I think it becomes very difficult to sustain that position, merely because the idea of Pakistan as a polity wasn’t particularly at play during the middle of the 19th century. As a concept, it developed rather late, in the period leading up to Partition in the middle of the 20th century. I direct you towards the work of David Gilmartin on the idea of Pakistan in order to get a better sense of the newness, as it developed over the 20th century.[viii] So it is difficult, I think, to make the argument that Naomul was a traitor to Pakistan when, in fact, the idea of Pakistan wasn’t actually in existence in any meaningful way during Naomul’s life. You might then argue and ask whether Naomul was a traitor to Sindh? This is also a problematic argument in fact because the plain truth of the matter is that Sindh as a unified nation or nationality or polity really only came into being over the course of 19th century. If you remember, in the pre-colonial, pre-annexation period, the geographical region that we now call Sindh was divided up into various semi-independent sovereignties. You had the Mirs of Khairpur, the Mirs of Mirpur and the Mirs of Hyderabad. There were three different houses. The largest and most powerful of these groups were the Baluchistani Talpur Mirs of Hyderabad. The Talpur Mirs of Hyderabad ran their state in a rather decentralised way. They were called the Char Yar, or the four friends. But it would be inaccurate to talk about Sindh as a unified polity, at least during the course of the first half of the 19th century. Sindh as a political and social unit and the Sindhi national identity becomes much more coherent in the course of the 19th century. It would be inaccurate to take social categories that occur after Naomul’s life and apply them to his actions in a more familiar time period. So it’s hard for me to conceptualise Naomul as a traitor to Sindh, given the fact that the region didn’t have quite the same coherent polity and national identity that developed later on, after his death, starting in the latter part of the 19th century and becoming much more clear during the 20th century.

East India Company influence

How did the East India Company annexation of Sindh in 1843 impact the region socio-politically? Well, it’s safe to say that the impact of annexation by the East India Company and the subsequent colonial rule of South Asia by the British had a rather uneven impact on Sindh through the 19th century. In some domains the changes that were brought by annexation and colonisation were felt much more intensely than in other areas. So, for example, if you look in the domain of agrarian social structure power relations, it’s easy to make the argument that the impact of colonialism was, in fact, not so sharply felt by many at the local level.

Now the reason for this has to do with the actions of Charles Napier in 1843 or 1844, when he essentially called in all of the land owners (all the zamindars, waderos and jagirdars) to come to a big durbar to essentially reaffirm their allegiance to the British colonial state and to the East India Company in lieu of the Amirs. And what he ended up doing was merely reaffirming all of the land holdings, all the rights to collect taxes, and ownership of land that had previously existed. Now this caused a lot of confusion for the British. Because one of the major sources of revenue for the East India Company state was the taxation of agrarian produce. And if, as Napier did, the Company merely reaffirmed all of the titles and rights to the product of the land, on the part of the indigenous elite, it left these colonial administrators with no actual knowledge of the economic fecundity of the region. In fact, it took them a long time to sort this all out. The first printed comprehensive land settlement work wasn’t done until the 1860s, although they started working on it in the 1840s to clear up the rules about who owned what. And the reason for this was, of course, because agrarian taxation was one of the most important sources of income that the East India Company had at this given time. Now what all this has meant is that a number of different historians, who have done some excellent work, have made an argument (that, I think, can be sustained) that, in fact, the impact of colonialism on agrarian social structure in Sindh was relatively light. What they had was a policy of ruling the elites and not actually ruling particularly directly. And, in part, this was the reason that they didn’t have the kind of knowledge that was required for that kind of direct/local/on-the-ground rule, on account of Napier coming in and reaffirming all the rights and privileges of all the indigenous land owners in Sindh following the annexation of the region.

Now, having said that, if you take a look at the domain of social structure in agrarian Sindh, you can make the argument that the impact of the East India Company socio-politically wasn’t that great on the ground [but] you can look at other domains and make the argument that it was quite transformative in its nature. Sindh became a sort of more singular administrative and political unit in a way that it hadn’t been before. Prior to annexation in 1843, Sindh had been divided into three semi-independent kingdoms ruled three different Amirs. This whole situation was washed away and the entire region was, subsequently, put under Napier as a governor, who reported directly to the Governor General in Calcutta. In 1847, the situation changed and Sindh was put under a Commissioner, who directly reported to the Governor of Bombay who, then, reported to the Governor General in Calcutta.

But the point that I want to make is that, regardless of both these issues or both these time periods (the period between 1843 and 1847 or after 1847), Sindh developed a much more singular political structure and administrative structure and this was a great transformation. It gave it a certain sense of unity that allowed people to begin imagining themselves as part of a particular, singular, not only polity but, I dare say, nation. And we see this development of the idea of a more coherent Sindhi national identity developing in the latter part of the 19th century, in part, as a result of its integration into the British Empire. And we see this, for example, in the area of scripts. Prior to the British annexation of Sindh, Sindhis wrote the Sindhi language in a whole variety of scripting systems. When the British came in, they said “now this isn’t going to work” and, to gloss over a very complicated debate, the British colonial state decided that Sindhi would be written in one script and that would be in naskh, which is the Arabic script. What this did was it provided a more singular way to communicate. A more singular way for the people of Sindh to understand themselves as Sindhis. It gave them a more unified language and scripting system on which to base or to imagine, if you will, a more unified national identity. This particular development was very much a result of decision-making that was within the British colonial state. Now the British colonial state—say, for example, on this scripting issue—did consult indigenous ‘experts’. In the case of the fixing and codification of the script, what happened was that an indigenous committee was set up and they attempted to make suggestions and modifications to the form of naskh that the British colonial state had decided was going to be the writing system for the Sindhi language. They submitted a report to the Commissioner of Sindhi, Bartle Frere, in the early part of the 1850s and Bartle Frere’s response to them was that you have misunderstood your position. Your position, he told them, is merely to suggest indigenous texts that we can put into the script and thereby train our British colonial officers to become fluent in the Sindhi language. He informed the committee of indigenous experts that it was not their job to make suggestions about—or improvements on—the script that had been decided upon following the suggestions of Richard Burton.

So we have a situation here in which you can quite directly show how the impact of the British colonial experience and annexation by the East India Company was very profound on the socio-cultural life of many Sindhis. And that is [in] the choice and the decision to write the Sindhi language in naskh is directly related to decisions on the part of the British colonial state following the annexation in 1843.

I believe that the final decision on the naskh issue was in 1855 or 1856. This was a profound transformation that increasingly allowed Sindhis to think of themselves and communicate in a singular script and to think of themselves as a singular nation or sort of identity, or imagine themselves as a more singular identity.

How and why did the East India Company set up operations in Sindh

I’m going to answer this in the sphere of research I know best, which is the annexation. The British interest in Sindh continued to increase right through the course of the 19th century. A lot of the interest was not necessarily due to economic interests but due to political interests. But having said that, the East India Company often framed its interests in terms of economics. So, for example, if you look at the British literature in the 19th century on the issue of Sindh, you find a lot of individuals talking about the importance of free trade. This was consistent with the British Empire across the world as well as South Asia, this emphasis on free trade. The idea behind this was, of course, to open up the Indus. Sindh, with its Indus, was described by Eastwick as a Nile-like paradise.[ix] Opening it up to free trade would be a way to potentially gain access to markets in Central Asia. Now, of course, this was only part of the story. Free trade was often wielded, right through the 19th century (and to some degree even today), as a tool for justifying imperial expansion and interventions. In reality, one of the things that the British were interested in, with regard to Sindh, was to attempt to check what they viewed as a threat to their imperial sovereignty in South Asia by the Russians, who had been expanding their influence throughout Central Asia during the course of the 19th century. So the interest in Sindh and the annexation by the East India Company was, in many ways, a part of what they called The Great Game: The great game of imperial cat and mouse that was occurring in Central Asia, as well as other places (such as Persia), between the British Empire and the Russian Empire. So the interest of the East India Company in Sindh was often expressed in terms of economic interest (and the desire to expand free trade in the Indus and Central Asia), in fact, had a very profound and important political dimension attached to the Great Game and the competition for imperial power between the East India Company, representing the British Empire, and the Russian Empire. Now, having said that, let me also say that the British were also interested in South Asia for economic reasons that were not attached to free trade. And I’m thinking of the scholarship of Wong[x]. Wong wrote a very interesting article, some years ago, about how the British were interested in annexing Sindh and extending their influence into Sindh not for free trade purposes but the opposite of it—for closing down trading opportunities. For those of you who are familiar with the history of South Asia and the East India Company in the 19th century, you’ll know that it’s a history of increasingly restricted monopolies. As in the Charter Act of 1832, where you see a major constriction on the commodities and goods that the Company is allowed to have a monopoly on. Now, this leads to a couple of different things. One, at least, to an increasing interest in the Company acquiring land because land taxes on agrarian products were not excluded from the Charter Act as a domain from which the Company could extract wealth and taxes. As a result, you see in the period after the 1832 Charter Act, an increasing territorial expansion of direct rule by the East India Company in South Asia. And the reason for that is land taxes: it was one of the few areas the Company still had control over as an important source of revenue. Now, the other part of the story is that the 1832 Charter Act excluded opium from competition, from free trade. Opium was still a monopoly held by the East India Company. Wong argues that the East India Company was interested in extending their influence and openly annexing Sindh as a result of wanting to shut down, not promote, trade routes for opium that competed with those of the East India Company. Wong’s article is explicit in saying that the Company’s interest in Sindh had nothing to do with free trade—as many of their public documents stated—but for exactly the opposite reason. They wanted to cut down on trading opportunities in a particular commodity that they retained a monopoly on. And it was particularly important for the Company to shut down competing trade routes for opium to China. The reason for this was, as I mentioned, the sources of income for the Company after the Charter Act of 1832 were increasingly affected and land taxes, over the territory they ruled directly, was one area that it was dependent upon to finance itself and the other area was opium production and sale of opium to China in particular. 1840s is the period in which we have the Opium Wars, which were wars fought by the Company in order to protect its right to keep the Chinese addicted to opium, a product that it was producing in South Asia.

About the term Bhaiband

Bhaiband is the indigenous social category that is used to talk about the Hindu traders and merchants of Sindh. About the origin of the term, I don’t have a definitive sort of statement or conclusion. However, I can say a couple of different things that are relevant to understanding the term and what it tells us about the broader socio-cultural geography of Sindh as a region.

The term itself, if you look at the etymology of the words, is broken down into two words. One is bhai, the common Sanskrit-derived Hindi word for brother, and the other is bandh. Now the bandh part of this comes from bandhna or to tie, or to bring together. So quite literally the translation of this is ‘the tying together of brothers’ and that’s why the term Bhaiband has often been translated as ‘brotherhood’. Now what’s important about this term, that you’ve already maybe gathered, is that it comes as a marker of socio-cultural identity out of the Sanksrit-based linguistic traditions. Now what’s important here is that some of the other ‘Hindu’ groups of colonial and pre-colonial Sindh have histories of terminology that are in fact very different. So, if we take, for example, a look at the other major dominant group, in pre-colonial Sindh, of non-Muslims, these would be the Amils. We have a situation in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh. The area of capital and wealth was very much dominated by Bhaiband traders who controlled the power of capital. On the other hand, you had a group called the Amils, who controlled the power of the state. Now, the genealogy for the term Amil comes out of the Persian tradition and refers to the Mughal administrative category of Amal. Not Amil but, rather, Amal. This is a Persian term that is used to refer to a government administrator and was a term that was, in fact, used in the Mughal administration. What we have here is a really fascinating example of the two dominant moieties of the ‘Hindus’ in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh having somewhat different genealogies, although both of them were part of a larger umbrella group called the Lohana. Genealogies for the term that they called themselves then point, one, to an Indo-Persian terminology and the other points, in fact, to a more Sanskrit terminology. And what’s interesting about this is the accommodation of both of these traditions under a sort of singular category. What it points towards is the traditional kind of cultural ease and mix that has characterised, at least up to the 20th century, the socio-cultural condition of Sindh—where the hard and fast categories based on communal understandings of history between Hindus versus Muslims don’t particularly hold very well. I think the term Bhaiband, with it sort of leaning towards Sanskrit linguistic traditions and the Amils with their term and that category glancing towards the indo-Islamic and Persian traditions under one singular community category, the Lohana, points towards this easy mixing and flowing across religious boundaries which hardened much later, in the 19th century and leading up to Partition in the 20th century. So, while I don’t have an idea on the origin of the word Bhaiband, what it does point to is what I think are some important and very interesting facts about the nature of socio-cultural life and the fluidity of certain religious categories and practices as socio-cultural categories during the colonial and pre-colonial period.

How is it that conflict between various indigenous groups in Sindh facilitated the annexation of Sindh and how it is that this conflict may or may not have played a role in the formation of the modern Sindhi diaspora

Let me roll this question back a little bit and talk not historically but anthropologically, particularly about the competition and the relationship (and the hierarchies) of social power among the Lohana in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh. As I mentioned previously, the Lohana are an overarching socio-cultural category, a socio-cultural category that has been in existence in Sindh since at least back to the medieval period. And if you’re interested in the early histories of this category I suggest you read Derryl MacLean’s work on medieval Sindh and the Arab invasions.[xi] What happened following the Arab invasions, as Derryl MacLean illustrates, was a depopulation of this particular social category. As increasing numbers of migrants came into Sindh in the twilight of the Mughal Empire in the Punjab (and those groups migrated looking for economic opportunities and employment opportunities in Sindh and in successor states in the 18th century), you had these groups being integrated into the Lohana category. Now, over some time, many of these groups who were coming in, migrating in the course of the 18th century, were Khatris. And Khatris with experience in government administration. So we see a development, [the] bifurcation of the Lohana community into two separate endogamous moieties. One of these is based on the pursuit of the power of capital, the Bhaibands, and the other is those who rotated their identity around the pursuit of the power of the state—the Amils. But within the Lohana category, these two increasingly endogamous groups, that’s not to say that there weren’t occasionally intermarriages between these two groups but they became increasingly less common. In part that’s because marriage in South Asia is a marker of social distinction and status. It occurs all across South Asia and even in Sindh, as in this example, that one way that you mark your distinction as being separate—either as being superior hierarchically or inferior hierarchically from another groups—is by allowing marriage alliances or not allowing marriage alliances. So we have a situation in Sindh of Bhaibands and Amils becoming increasingly endogamous and a distinction, a status distinction, subsequently happening, where Amils began considering themselves (because of their association with the state) as being of higher social status and standing than Bhaibands. And this is a social distinction that continues with the community until today to varying degrees. Although, to be honest, Partition has helped obliterate some of this power distinction between Amils and Bhaibands within the Lohana community. However, during the colonial and pre-colonial periods (it’s important not to read back the postcolonial into the colonial) this distinction between being Amils and being Bhaibands was very profoundly understood and the distinction of Amils being superior/more sophisticated/more educated than Bhaibands (and looking down upon them) was something profoundly felt within the social dynamics and interactions amongst Sindhis who were of the Lohana category. Now, one of the things about Naomul was that he, in fact, used his close association with the British colonial state/with the East India Company, in many ways, to become an Amil. This was recognized when he was given the official government position of Deputy Kardar (land revenue official) of Karachi. So Naomul’s relationship with the East India Company, in many ways, had little to do with being a traitor(a traitor to what, as I mentioned earlier, is a big question) but rather using and understanding the social hierarchies of his community to transform himself from exclusively being a Bhaiband and, increasingly, appropriating an Amil status.

Now, this attempt to invert the social hierarchies between Amils and Bhaibands, within the Lohana community, increasingly developed or encountered pushback from Amils, who were initially distanced because of their strong association with the Amirs’ states, as the Amirs states’ ‘officers of despotism’. The Company, ultimately, had a shift in priority in the 1840s away from a need to finance colonial expansion and, ergo, a relationship with wealthy Hindu traders like Naomul, and towards a need to administer a colonial state. And what you see during this time period of the 1840s through the 1850s is a shifting of alliances away by the colonial state and the East India Company away from Bhaibands, like Naomul, and towards the Amils. As the shift happened, it put Bhaibands, like Naomul and others, in a very awkward position where they, in fact, faced a backlash by Amils against Bhaibands for having stepped out of their social category and having tried to disrupt, or invert, the power relations between Amils and Bhaibands—by Bhaibands using their close association with the East India Company to essentially become Amils. What we see during this period are opportunities opening up for Bhaibands, as this sort of backlash is happening. Economic opportunities are opening up for Bhaibands in other parts of the British Empire. One of the things about being a citizen of the Empire is that you had the right to be able to travel and settle in different parts of the empire. So, you see the opening up of opportunities for Bhaibands in the British Empire at a time and place in which the emphasis and close relationship between Bhaibands and the British colonial state was shifting away from them (and away from the need to finance the British colonial state in Sindh) to the need to administer it, and a shift away from Bhaibands and a shift towards political alliances with Amils, reintegrating themselves into the structures of power administration in the post-annexation period. So you can actually sort of read the origins/beginning of the Sindhi diaspora (in the 18th century, or part of the diaspora in 18th century). Of course, Markovits has done some really wonderful work on this that sort of predates the middle of the 19th century.[xii] But you can peg it to this internal debate and attempt by Bhaibands to invert the social structures and hierarchies between them and Amils within the broader Lohana category. So, there is an actual profound relationship between conflict between various indigenous groups in Sindh, particularly the Amils and Bhaibands in the post-annexation period, and the expansion of the Sindhi diaspora staring in the middle of the 19th century.

Bhaibands and Sindhworkis

Who are the Sindhworkis and how do they relate to the social categories that I have been talking about today? So, Sindhworkis are, in fact, a type of Bhaiband. The Bhaibands, as I mentioned before, have historically rotated their sense of identity around a pursuit of capital power. Within that particularly social category, there was a hierarchy. A hierarchy based on wealth. At the higher end of the Bhaiband community, you had very wealthy financiers who were capitalists, if you will, involved in many different kinds of business, all the way down to, the local level, Bhaibands who were engaged in much smaller forms of capital behaviour, grain merchants for example. One of these smaller less affluent Bhaiband groups were individuals and families who took to trading in traditional Sindhi arts and crafts. Or what was called, by the British, ‘Sindhwork’. These were arts and crafts were not produced by ‘Hindus’ but by Muslim artisans in Sindh and were taken as a domain of economic trade which became dominated by a particular group of Bhaibands, who then subsequently got identified by the British and appropriated this terminology to talk about themselves as Sindhworkis. Some of the first Bhaiband groups to leave Sindh were, in fact, members of the Sindhworki groups who peddled and sold, in various retails and stores, various products of Sindh. And, as a result, some of the first members of the post-annexation Sindhi diaspora were these Bhaibands, called Sindhworkis, who went out to other parts of the British Empire which they could—now as citizens of the empire—now settle in in order to make and establish new lives for themselves following the annexation of Sindh and following the sort of rotting of internal relations between Bhaibands and Amils [that] I discussed earlier in the post-annexation period.

The first sort of Sindhis to migrate in this post-annexation period were not the large scale wealthy Bhaiband financiers. These, in fact, were lower groups of less affluent means. And this is, of course, a pattern of behaviour quite consistent across the British Empire in general. Many of the people involved—individuals involved in the expansion of the British Empire—in the settlement of the British Empire were not from the elite echelons of British society. Nor was this the fact with, for example, the Sindhis. Very few Amils, who considered themselves the elite strata of Sindhi society, initially took advantage of these opportunities of being citizens of empire to establish themselves in businesses in foreign locales: South East Asia, East Asia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Jakarta and places like this. So, this is a general sort of pattern that’s consistent with behaviour across the Empire, where you had Sindhworkis—who were lower echelon, less wealthy, and less well-off Bhaibands—taking the opportunity to migrate within the geography of the British Empire to establish and make new lives for themselves elsewhere, outside of their homeland. And, in many ways, this is consistent even with the behaviour of the British who came to South Asia themselves for similar reasons, to look for better opportunities. The colonizers who came to South Asia were often not the elite cream of British society. Same story as with Sindhworkis: they were Bhaibands, but not of the wealthy or high classes, be they Amils or the more wealthy Bhaibands who dominated trade and capital exchanges in colonial and pre-colonial Sindh.

[i]Sandria Freitag, Collective Action and Community: Public Arenas and the Emergence of Communalism in North India (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990); Gyendra Pandey, The Construction of Communalism in Colonial North India, 3rd Edition (Delhi & London: Oxford University Press, 2012).

[ii]Matthew A. Cook, “Getting Ahead or Keeping Your Head? The ‘Sindhi’ Migration of Eighteenth Century India,” in Michel Boivin and Matthew A. Cook, eds., Interpreting the Sindhi World: Essays on Society and History (Karachi & London: Oxford University Press, 2010), 133-149.

[iii]Steven Ramey, Hindu, Sufi, or Sinkh: Contested Practices and Identifications of Sindhi Hindus in India and Beyond (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2008).

[iv]Allen Keith Jones, Politics in Sindh, 1907-1940 (Karachi & London: Oxford University Press, 2002).

[v]David Cheesman, Landlord Power and Rural Indebtedness in Colonial Sind (London: Routledge/Curzon, 1997).

[vi]Matthew A. Cook, Annexation and the Unhappy Valley: The Historical Anthropology of Sindh’s Colonization (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2016).

[vii]Ibid.

[viii]David Gilmartin, Civilization and Modernity: Narrating the Creation of Pakistan (New Delhi: Yoda Press, 2014).

[ix]Edward Eastwick, Dry Leaves from Young Egypt: Being a Glance at Sindh Before the Arrival of Sir Charles Napier (London: British Library, 2011[1851]).

[x]J.Y. Wong, “British Annexation of Sindh in 1843: An Economic Perspective,” Modern Asian Studies 31(1997): 225-244.

[xi]Derryl MacLean, Religion and Society in Arab Sind (Leiden & New York: Brill, 1989).

[xii]Claude Markovits, The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947: Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Life in Sindh for officials of East India Company: http://scroll.in/article/816748/a-glimpse-into-the-life-of-an-east-india-company-official-posted-in-sindh-during-british-rule

About Karachi: http://www.dawn.com/news/1245005