Pather Panchali ('Song of the Little Road') [1955]

Amidst huge financial constraints was born a great masterpiece—and a cinematic movement. Pather Panchali heralded the ‘parallel’ school of filmmaking in India, realism being one of its core concerns. Shot over a period of four years, it is an adaptation of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novel of the same name, written in 1929. The film revolves around the everyday trials of a family of five, living in abject poverty in a village in Bengal, and trying to make both ends meet. However, it transcends mundane anxieties and explores the joy in the tiniest of incidents, through the two child protagonists Apu (Subir Banerjee) and Durga (Uma Dasgupta). Subrata Mitra’s cinematography, with the play of light and shadow, and Ravi Shankar’s background score helped the film reach unprecedented heights.

Aparajito ('The Unvanquished') [1956]

The second film in the ‘Apu Trilogy’ traces the transformation of Apu (Smaran Ghoshal) from a child to an adolescent. The scene shifts from the village to Varanasi and then to Calcutta, although the rural past continuously stands in Apu’s way as he tries to take significant decisions to change his unenviable condition. The highlight of the film is the tension between the mother (Karuna Banerjee) and Apu as the latter moves away from his family and roots and the former tries to hold on to her dear son, the closest person in her life, after the demise of her daughter and husband. This was also an adaptation from Bandyopadhyay’s Pather Panchali and Aparajito, with Ray taking some crucial liberties while dealing with the mother-son relationship. It is the first film to win the Golden Lion and the Critics Award at the Venice Film Festival in the same year (1957).

Parash Pathar ('The Philosopher’s Stone') [1958]

Parash Pathar was yet another adaptation of a short story by Parashuram (Rajshekhar Bose), and criss-crosses multiple genres of filmmaking. It is at the same time a fantasy, a comedy, has elements of magical-realism, and above all—a satire. It laughs at Bengali middle-class aspirations and their desire for more material gains, and what happens when they have too much of it. A philosopher’s stone upturns the fate of a family, as they start hobnobbing in the elite circles of the city, without being educated in their ethics and code of conduct. A comment on the hollowness of the upstarts of the society, it had Tulsi Chakravarty, Ranibala Devi, and Kali Banerjee in the leading roles with the regular off-camera contributions of Subrata Mitra, Dulal Dutta (editing), and Ravi Shankar.

Jalsaghar ('The Music Room') [1958]

Interestingly, Ray’s comment on people who have suddenly become wealthy continues in his next film Jalsaghar. Based on Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay’s short story, it traces the last days of the zamindari system in 1930s' India, where a forlorn Biswambhar Roy (Chhabi Biswas) reminisces about the proud days as a zamindar, when his palatial house had regular jalshas (musical concerts). Now, having lost his wife, son as well as prestige and status in the society, his life is falling apart around him, like the decadent ghostly house which he inhabits, along with a couple of servants. In a climax Ray pits this house which had a great name for centuries with one which couldn’t boast of a lineage, but had endless liquid money. It is a conflict between (high) culture and cash, between ‘banediyana’ and business, as it were, as Roy wants to overpower his neighbour and bring back his lost glories for one last time. Begum Akhtar, Bismillah Khan, Roshan Kumari, and Waheed Khan make on-screen appearances.

Apur Sansar ('The World of Apu') [1959]

The final film of Apu Trilogy is an adaptation of the second half of Bandyopadhyay’s novel Aparajito and portrays the harsh reality of a huge section of the Bengali youth of in the middle of the 20th century—educated but unemployed. Apu (Soumitra Chatterjee), here has grown up to be a writer, and gets married quite accidentally, and what follows is a narration of a short-lived happiness followed by a sudden loss in his life, leading Apu to move away from his known circles. The trilogy wraps up with a happy reconciliation, with the family of Apu coming full circle. Ray introduces Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore, who’ll later on become two of the most recognizable faces of Indian cinema.

Devi ('The Goddess') [1960]

Another adaptation, this time from the short story by Prabhat Kumar Mukherjee, saw Ray going back a century to comment on yet another aspect of Bengali society in particular, and Indian cultural practices in general. The film is set in an 1860 Bengal village and deals with questions of the deification of the feminine, of superstition and of religious conservatism. It is a portrayal of what orthodox belief could make a man (Kalikinkar Roy, played by Chhabi Biswas) do to another woman (Doyamoyee, played by Sharmila Tagore), and how a miracle can reinforce certain belief systems in society. It is a confrontation between rationality (brought forth by Umaprasad, played by Soumitra Chatterjee) and the religious—a theme haunting Indian society for centuries. The haunting character development of Doyamoyee—that of the appropriation of the divinity imposed on her—and her deranged state, is a further comment on the existent state of affairs. Music is by Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

Teen Kanya ('Three Daughters') [1961]

Ray adapted three short stories into three short films, under the said title, as part of Tagore’s birth centenary tribute. Three women—a child, a young woman, and a married lady are the protagonists.

In ‘The Postmaster’, Ratan (Chandana Banerjee) is an orphan and a carer for a new postmaster (Anil Chatterjee) who has arrived in her village. Ray portrays the attachment the child develops towards Nandalal (Chatterjee), and the heartbreak she experiences thereafter. In Ray’s handling, a child’s psyche comes out in all its complexities.

In ‘Monihara’ ('The Lost Jewels'), Ray explores the supernatural, through the story of a wife of a rich man, addicted to hoarding jewellery. A chilling climax awaits, as the fate of the couple goes horribly wrong, due to a failed business, insatiable greed, and—a murder.

In ‘Samapti’ ('The Conclusion'), Ray tracks the innumerable pranks of Mrinmoyee (Aparna Sen), with Amulya (Soumitra Chatterjee) being at the receiving end of most of these. The story is of a gradual coming to adulthood, with all its responsibilities and attached respectability, as Mrinmoyee grows from a sprightly girl to a woman in love with her husband.

Kanchenjungha [1962]

This is Ray’s first film which is not an adaptation from a work of literature. This is an interplay between nature’s grand setting and men’s trivial machinations. Set against the pictureque Darjeeling, Ray delves deep into how relationships are forged and broken. A vacation, which could have led on to the beginning of a relationship, not entirely of the making of the two involved, leads to a self-realization, as Monisha (Alakananda Roy) goes against her father’s wishes, as the nature continues to portray the general mood of the proceedings throughout the film. Ray experimented quite generously with the making—with multiple plot-points, flashbacks and fractured narrative. Not to mention shooting in colour—again a first for him.

Abhijan ('The Expedition'] [1962]

Ray adapts Tarashankar Bandyopadhyay’s novel by the same name, which has a male protagonist who is an ill-tempered Rajput taxi driver, constantly at war with the world. His woes heighten when he is separated from the only thing beloved to him—a vintage 1930 Chrysler. The film is a rollercoaster ride where Narsingh (Soumitra Chatterjee) tries to uphold his Rajput pride and morality but gradually gets drawn into extremely shady transactions involving drugs and women. Both women in the film, Neeli (Ruma Guha Thakurta) and Gulabi (Waheeda Rehman), blur his conception of ‘good’/moral and ‘bad’/immoral, and, from the depths he has stooped to, he tries to look for salvation.

Mahanagar ('The Big City') [1963]

An adaptation of Narendranath Mitra’s short story ‘Abataranika’, this is Ray commenting on contemporary Calcutta. This is the post-independence post-Partition Calcutta, which is the densest city in the world in terms of population, with cut-throat competition in the job market. The 1950s were the years women had to come out of their house in search of jobs and Arati Mazumdar (Madhabi Mukherjee) represents the journey of these middle-class women, filled with dread, hope, and anticipation. The anxieties of a woman going out for work, strains in relationship with the unemployed husband, and Mazumdar becoming an independent woman finding her voice in the deafening cacophony of the chaotic city, make the film a text of its time. Ray introduces Jaya Bhaduri (later, Jaya Bachchan) in this film.

Charulata ('The Lonely Wife') [1964]

Ray adapted Rabindranath Tagore’s 1901 novella ‘Nastanirh’ (The Broken Nest’), which shows the angst of the rising class of educated women in the second half of the 19th century in upper and middle class Bengali households. Charulata (Madhabi Mukherjee) is an educated and creative individual, curious about the ways of the world, but lacks an adequate platform to share her thoughts or a like-minded individual to converse with, on equal terms. Her mundane life changes forever with the coming of Amal (Soumitra Chatterjee), that much needed company and creative foil to her drab existence. Issues of disconnect, trust, loyalty, and unspoken love all intermingle with one another as the lives of everybody concerned take a turn, from where there is no going back to the days of comfortable pretense and undisturbed monotony.

Kapurush-O-Mahapurush ('The Coward and The Holy Man') [1965]

Adaptation of two short stories lets Ray deal with questions of indecisiveness, self-confidence, faith, and manipulation. In ‘Kapurush’, from Premendra Mitra’s ‘Janaiko Kapurusher Kahini’, chance brings together a couple, who had parted ways years back, due to the reluctance of Amitabha (Soumitra Chatterjee) to take the leap of faith. Could such a relationship be resuscitated through a change in circumstances?

‘Mahapurush’, from Parashuram’s ‘Birinchibaba’, is a comic take on the blind faith in godmen deeply felt by a large part of society. The tall claims of a Holy Man are brought into question as the followers tries to grapple with such mischief.

Nayak ('The Hero') [1966]

Ray’s second original screenplay and his first collaboration with Uttam Kumar—the greatest superstar in Bengali film industry. The setting becomes a metaphor in itself, a train journey, tracing the life of a hero—Arindam Mukherjee (Uttam Kumar), at the peak of his stardom. As he faces an insightful Aditi Sen Gupta (Sharmila Tagore), an editor of a women’s magazine, he comes to terms with his real life, a far cry from his reel self. As Aditi herself is not one of the admirers he constantly encounters, a lonesome Arindam confesses his betrayals of his mentor and friends, the sadistic pleasure he received in taking revenge on his co-actor, and the struggle that he had to undergo to reach where he is today. Such revelations represent Ray's comment on the murkier side of the film industry and the need to look beyond the screen persona of actors. Bansi Chandragupta’s art direction deserves special mention.

Chiriyakhana ('The Zoo') [1967]

This was Ray’s first adaptation of a crime novel, written by Saradindu Bandyopadhyay. Byomkesh is not an average detective, but a satyanweshi (investigator of truth). Byomkesh (Uttam Kumar) and Ajit (Sailen Mukherjee), his assistant friend investigates multiple murders in a colony, inhabited by all kinds of social misfits. The film had a large set, with a huge cast, and won the Best Director and Best Actor awards at the 15th National Film Awards.

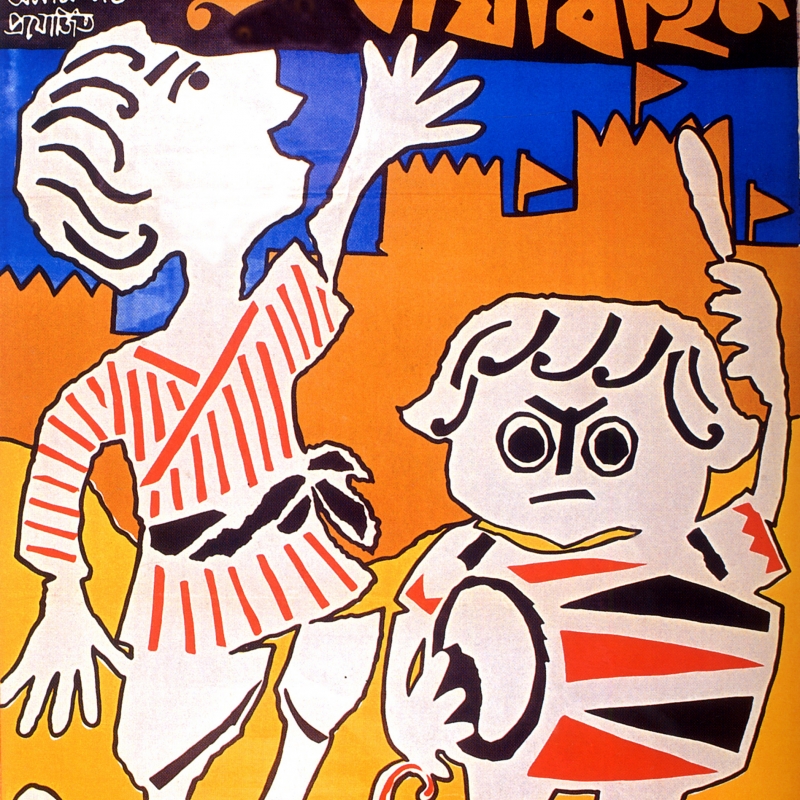

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne ('The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha') [1968]

This was the beginning of one of the most successful of children’s film series. Having a record opening, Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne was based on the story of Ray’s grandfather Upendrakishore Roychowdhury, which was published in Sandesh, way back in 1915. It is on first view a film for the children, but is deeply multi-layered and an out-and-out satire on the misuse of power on the one hand and a celebration of honesty and innocence on the other. Goopy (Tapen Chatterjee) and Bagha (Rabi Ghosh), outcasts from their respective villages, suddenly find themselves at the receiving end of three boons which magically enhance their artistic talents and ensure unlimited food and mobility. It is then a matter of choice of how to make use of such outlandish powers, as the two find themselves in the midst of a full-fledged war. The film was made with a big budget—an uncommon phenomenon in Ray’s films—and shot in multiple locations around the country. Anup Ghoshal’s rendering of the songs is an added bonus.

Aranyer Din Ratri ('Days and Nights in the Forest') [1969]

Adapted from an allegedly semi-autobiographical novel by Sunil Gangopadhyay, this is Ray exploring the lives of four youths—differently placed in the socio-economic structure—and the interactions between the city breds with the primordial. As Asim (Soumitra Chatterjee), Hari (Samit Bhanja), Sanjoy (Shubhendu Chatterjee), and Sekhar (Rabi Ghosh) deliberately let go of their urban ways to immerse themselves in the tribal ways of Palamou, conflicts emerge as they indulge themselves in country liquor and women, but tries to put up their best foot forward while interacting with another Bengali family, holidaying nearby. Pretensions fall away, and being far away from their created identities, they come to terms with their deepest desires, insecurities and fragile egos. Aparna (Sharmila Tagore) and Jaya (Kaveri Bose) contribute to and shares the inner journey.

Pratidwandi ('The Adversary') [1970]

This is the first film of Ray’s ‘Calcutta Trilogy’, an adaptation of Sunil Gangopadhyay’s novel. Answering to criticisms that he is not concerned with the contemporary horrors of his city, Ray engages with the mass unemploymentof the youth of that time, a result of the partition of Bengal and the consequent migration on one hand, and a steady deindustrialisation of the state on the other. The city gains an identity of its own, through its crowded buses, congested roads, empty cinema halls, coffee shops and the Princep Ghat. When political boundaries were sharply drawn, Ray portrays a young Siddhartha (Dhritiman Chatterjee), always in a dilemma about his career, his relationships and his future. Floodgates of emotions open as he constantly fights with the society, his pitiable middle-class ethics, and his repressed desires.

Seemabaddha ('Company Limited') [1971]

In the second film of the ‘Calcutta Trilogy’, adapted from Mani ‘Shankar’ Mukherjee’s novel, Ray’s moves away from the middle-class existence and takes the audience to the highrises of Calcutta. Shyamalendu Chatterjee’s (Barun Chanda) apartment is far away from the violent streets and he is fighting a wholly different battle—a competition for promotion. Through Tutul’s (Sharmila Tagore) eyes, one sees elite Calcutta with its salons, racing tracks, and restaurants. However, amidst such unending prosperity, Tutul finds how Shyamalendu is constrained to win a race in his corporate life, which he must fight in the most unethical ways possible.

Ashani Sanket ('Distant Thunder') [1973]

Ray shifts his gaze to one of the greatest horrors in human history—the man-made famine of 1943 in Bengal, which claimed five million lives. The story, originally a novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, is set in a village where the people can sense an impending danger as the price of staple food rises, leading to utter starvation. Keeping Gangacharan (Soumitra Chatterjee) and Ananga (Babita) in the forefront, the film captures the gradual destruction of the structures in rural Bengal—from socio-economic to interpersonal. As hunger looms large over the village society, caste identities are forgotten, class consciousness gives way to menial labour and deaths ultimately make way for mass displacement. Here again, Ray uses colour on a symbolic level, standing as a metaphor for life itself.

Sonar Kella ('The Golden Fortress') [1974]

This was the glorious debut of one of Bengal’s most loved detective Pradosh Mitter aka Feluda, on screen. A creation of Ray himself, Sonar Kella sees Feluda (Soumitra Chatterjee) along with his cousin-cum-assistant Tapesh Mitter (Siddhartha Chatterjee) criss-crossing Rajasthan trying to uncover the mystery related to a child, Mukul (Kushal Chakravarty), who has visions from his previous life. Ray here establishes his favourite way of telling a detective story—by showing the villains beforehand, therefore avoiding a whodunnit method of narration. Crime follows comedy and vice-versa, as Ray introduces Lalmohun Ganguly (Santosh Dutta), author of several crime fiction, as the other compatriot of Felu, thus completing the team of three. Sonar Kella also gave Ray the opportunity to work at length on one of his many personal interests—parapsychology.

Jana Aranya ('The Middleman') [1975]

The third and last film of the ‘Calcutta Trilogy’, Ray again explores the bleak atmosphere of '70s Calcutta, where education doesn’t ensure a job, and the traditional codes of sustenance are lost forever. Taken from a novel by Mani ‘Shankar’ Mukherjee, Jana Aranya traces how Somnath (Pradeep Mukherjee) must learn to let go of his preconceived notions of morality and take up the job of a middleman in the order-supply business against his wishes. Ray shows the burrabazar area of Calcutta, the hub of (predominantly ‘non-Bengali’) businessmen. It is a daily battle for survival, as Somnath not only dives headlong into this uncertain world, but also must forego his principles and pay a dear price for a more hopeful future.

Satranj Ke Khiladi ('The Chess Players') [1977]

Ray’s first film in Hindi, and the one with the biggest budget. The film called for it, as it was set in 19th-century Awadh (capital of Lucknow), right before the Revolt of 1857. Ray expands Munshi Premdas’s short story to tell two parallel but inter-connected stories, of the expansion of British colonial empire and the indifference and the inability of the Indian royalty and noblemen to do anything about it. As Nawab Wajid Ali Shah (Amjad Khan) remains in his world of poetry and music, General Outram (Sir Richard Attenborough) plots to take over his kingdom. The two chess players (Sanjeev Kumar and Saeed Jaffrey) lives in the comfort of denial and the confidence that their traditional glory is going to see them through in future as well. However, the tactics of the older world have little relevance in the present game of chess that is the global politics of colonialism. Amitabh Bachchan lends his voice for the narration.

Joy Baba Felunath ('The Elephant God') [1978]

The second Feluda film of Ray’s, it takes the audience to the narrow lanes and busy ghats of Varanasi, where Feluda (Soumitra Chatterjee), Topshe (Siddhartha Chatterjee), and Jatayu (Santosh Dutta) get caught up investigating a case of theft, and later on—murder. Ray introduces Felu’s arch-enemy Maganlal Meghraj (Utpal Dutt), the shady businessman, engaged in innumerable illegal transactions on a global scale. The story, as with Ray, is not just a crime thriller, but a social commentary and a travelogue rolled into one. Soumendu Roy’s cinematography deserves special mention. Reba Muhuri’s songs bring Varanasi alive on screen.

Hirak Rajar Deshe ('Kingdom of Diamonds') [1980]

The second film in the Goopy-Bagha series, it is a vicious commentary on authoritarian regimes, restraining freedom of thought and expression, and unquestioning acceptance of the same. The entire script is lyrical, except the dialogues of the local teacher, Udayan (Soumitra Chatterjee)—an indication of his resistance to the structure. Goopy (Tapen Chatterjee) and Bagha (Rabi Ghosh) faces the dictator, Hirak Raja (Utpal Dutt), who has mastered the art of brainwashing his subjects into believing that they are living in great harmony and prosperity. Udayan remains his only adversary, and Goopy and Bagha must rescue the poor subjects from the clutches of the king. It is said that this was Ray’s comment on the Emergency of 1975-77 and also the leftist government’s decision to do away with the teaching of English from the schools of West Bengal.

Sadgati ('The Deliverance') [1981]

A flim, with a running time of less than an hour, it is the second project of Ray’s in Hindi. Another adaptation of a Munshi Premchand short story, it looks at the age-old problem of the caste system and untouchability in the country. The trials faced by Dukhi Chamar (Om Puri) because of his low caste status, an identity that doesn’t leave him even after his death, brings to the fore the gross discrimination faced by a huge section of the population even to this day.

Ghare Baire ('The Home and The World') [1984]

Ray adapts Rabindranath Tagore’s novel to talk about the post-partitioned Swadeshi days of Bengal during 1905. As the movement against the British policies gain momentum, another change occurs in the house of Nikhilesh (Victor Banerjee), as he urges his wife Bimala (Swatilekha Chatterjee) to experience the world outside. The film handles the finer nuances of coming to terms with such new experiences, not only for Bimala but also for Nikhilesh and Sandip (Soumitra Chatterjee). The clamour for self-governance outside resonates in their lives as Bimala learns to take decisions for herself and question certain actions and intentions.

Ganashatru ('Enemy of the People') [1989]

Ray adapts Henrik Ibsen’s play An Enemy of the People, to deal with a theme he has repeatedly dealt with—prejudice, blind faith and unquestioning belief in religion. Dr. Ashoke Gupta (Soumitra Chatterjee) is the voice of reason as he tries to warn the villagers of a certain health hazard coming from the ‘sacred’ temple water. However, he finds himself at the end of much criticism from every quarter, including from his brother Nisith (Dhritiman Chatterjee). As the powers that be—officials to newspaper editor—leave his side, the helpless Dr. Gupta must find a way to persuade the public against their long-held beliefs. A chamber drama, Ray shot the film after a serious ailment that considerably restricted his mobility and filmmaking technique.

Shakha Proshakha ('Branches of the Tree') [1990]

This film, a joint Indo-French production, brings three generations under one roof to celebrate Ananda Majumdar’s (Ajit Bannerjee) 70th birthday. As the patriarch falls ill, tensions rise between his three sons (Haradhan Banerjee, Deepankar Dey, Ranjit Mallick), with the fourth son (Soumitra Chatterjee) being the moral compass, portrayed as mentally unstable. Petty politics lead to familial conflicts, long cherished desires are confessed, and couples share their differences in the bedroom as the joint family betrays its faultlines. And ultimately, a child’s (Soham) disarmingly innocent query, lays bare all the pretensions of a ‘happy family’.

Agantuk ('The Stranger') [1991]

Ray’s last film was an adaptation of his own short story titled ‘Atithi’ (The Guest). Tensions rise when Manomohan Mitra (Utpal Dutt) comes to the Bose family after 35 years, claiming to be Anila’s (Mamata Shankar) uncle. Ray lays bare questions of trust, which gains further relevance as proprietorial rights are up for the taking. Insticts of suspicion, of non-acceptance of Mitra’s story clouds certain judgement, leading to a nasty confrontation. Making Mitra a anthropologist who has seen the world with his own eyes, Ray engages with questions of modernity, development and basic human(e) values. Even in his last project, certain characteristic features running through almost all of Ray’s films—an eye for detail, the child as a crucial element in the plot development—are all too evident.

Special mention

Two [1964]

A 15-minute 'fable' as was declared in the opening credits, Two is a film without any dialogue, showing the rivalry between two kids—one from a rich background, the other living on the streets. One sees how a child’s happiness is not conditional on his economic affluence as bitter competition gives way to a more considerate understanding of the other.

Pikoo (Pikoo’s Day) [1980]

A short film made for France 3, Ray adapts one of his short story, with a child protagonist (Arjun Guha Thakurta) around whom events take place that are beyond his comprehension. As Pikoo’s mother (Aparna Sen) deals with her extra-marital affair with Hitesh (Victor Banerjee), she tries to keep her son away from the adult world and its complications. But such neat divisions become impossible, as the child gets mixed up in the whole conundrum.

Documentaries

Rabindranath Tagore [1961]

Made on the birth centenary of Rabindranath Tagore, Ray picks up elements from the highly eventful life of Tagore, to portray the latter’s creative brilliance and shifts in ideolog over the years. Ray contextualises Tagore’s life in the background of the Indian National Movement and the two World Wars.

Sikkim [1971]

Commissioned by the Sikkim royalty, Ray portrays the flora and fauna of Sikkim, the local markets, their festivals, diet, arts and crafts and various public institutions. It also shows the rituals in the monasteries as well as palace inside the palace grounds. The film was banned and the first public screening was only in 2010. A possible reason for such censorship could be the simultaneous portrayal of the utter poverty of the common people in contrast with the opulence of the royal household.

The Inner Eye [1972]

An ode to his teacher, Ray documents the experiences of Binode Behari Mukherjee, a painter and later on a sculptor, who loses his eyesight in his middle age. What it means for a person engaged with the visual arts to lose the power of eyesight, and how it shapes his artistic self is what the filmmaker tries to get to grips with.

Bala [1976]

Ray documents the on-stage movements of the famous Bharatnatyam dancer Balasaraswati and her off-stage life with her friends and family. Avoiding much experimentation in filmmaking, Ray lets the dancer do all the ‘talking’ through prolonged shots of her performances.

Sukumar Ray [1987]

Celebrating the birth centenary of his father, whom he lost at the age of three, Ray made his last documentary by going back to his roots and looking back at his own influences. It is more a history of his family over the course of the second half of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. Ray talks about his grandfather Upendrakishore and then about his father Sukumar—their contributions in the field of literature, illustrations and printing. Unlike any of his other documentaries, Ray left the narration to Soumitra Chatterjee.