Introduction

While the forests of Bastar has something in store for the dwellers across all seasons, the dwellers also respond to it with their seasonal awareness and sensitive engagement; while fibers and creepers are collected year round some of the forest produces are only collected in their specific seasons. The seasonality of occupations have a history and an ecology to it. Historically, as forests of central India came under the forest departments of the colonial masters and got governed through their laws, the governance of the forests underwent a paradigm shift. The forest were governed not anymore as a place of ‘dwelling’ or a habitat for forest dwelling communities, flora and fauna but rather as a resource pool which needed to be systematically exploited to reap benefits for the propagation of modern society. The laws of forest governance and management underwent changes. Most norms that are followed by the forest dwelling communities of central India today were formed over decades of interaction which amounted to varying degrees of compliance, resistance and negotiation in between the dwellers and the administrators (EPW 1989, Sivaramakrishnan 1999). Even today the plane of contestation remains and amongst many ways they are manifested through a seasonality of their engagement with the forest. Consequently winter season is primarily the season of ‘wage work’(EPW 1989). The dwellers often work with the forest department as seasonal wage labourers clearing out forests through legalized logging, landscaping or they work in their own villages to rebuild their houses, dig out ponds, wells or building bridges, check dams etc., across streams (EPW 1989). Along with wage work some of them also go into the forest to collect palm tree saps, gums and resins. While palm tree saps are tapped for quenching their thirst and as a celebratory drink, the resins are exchanged in the weekly haats for cash and other utilities.

Palm Tree Sap

Palm tree sap are extracted from two local varieties of palm commonly known as Chind and Sur. They are a flowering variety of palm. It is a native of Southeast Asia and it is called ‘sulfi’ tree in Chhattisgarh. The fermented sap (sulfi) is a favorite drink amongst the various forest dwelling communities of Bastar. For the Muria, Maria, Marar, Halba, Gara and Durvas the Chind and Sur trees have a special significance. For Muria’s of north Bastar when the daughters are married to a bastard son, then a sulfi tree is given to the bastard as a gift. If owners of sulfi trees do not have any children then the sulfi tree will pass on to the nephew of that person. The norms of succession also keep changing from one area to the other but what remains significant is the need to pass on the tree as a piece of property.

The trees which are full of sap and are ready to be tapped are called 'Gorga' in Gondi dialect. During the winter season a chind or a sur tree growing close to a water source can yield about twenty liters of alcoholic sap in a day. One tree is sapped for not more than five-six months in a year. Mostly the management of trees are done by a designated person from a village. The person is called ‘Tadial’ (Ramnath 2015). The tadial is not the owner of the trees but the warden. The owners of the tree have a contractual relationship with the tadial regarding the palm trees under the tadials management. The trees are sapped only when the tadial thinks its time to sap. The owners get a share only when the owner approaches the tadial in a specific time; conventionally, either in the morning or evening and, the tadial fetches the pot in which the sap gets collected (Ramnath 2015). The sap is generally collected in vessels made of dried and hollowed out gourds locally called a Bhurka.

Forest dwelling communities generally plant palm trees on their backyards or courtyards or farms adjoining their household called barhi. A chind or a sur tree can grow up to forty feet high and gets ready for sapping sulfi after 9 to 10 years. As the cold season approaches, the tadials start sapping the trees and continues for 4 to 5 months.

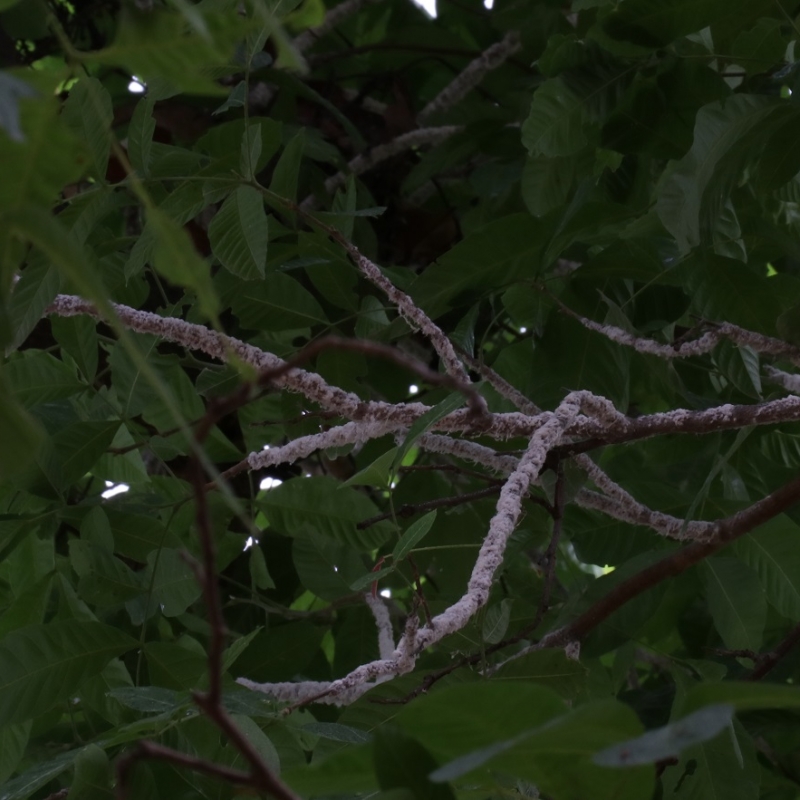

In the recent past sur and chind trees were getting infected by a fungus named Oxiforum Fisium which has dried out the trees and have become a thing of concern in Bastar.

Sal Resin

The sal tree is of great significance for the adivasi communities of Bastar. Each and every part of the tree is collected by the adivasis either for direct use in their household or sell as a product for industrial usage. The usage of sal is prevalent as a component for various pharmaceutical products. The fruits of the sal tree are used in the treatment of excessive salivation, epilepsy, and chlorosis. The powered seeds have insecticide properties. They are also used to treat dental problems, It is also used as component in face and hair washes as it cleanses the skin from oily secretions.

Within the adivasi community the leaves of sal tree are used for preparing rice cakes or smoking pipes. The leaves are also used to make platters, bowls, small baskets and many more. Distilled leaves produce oil which are used in perfumery. It is also used in flavouing chewing gums and tobacco. Dried and fallen leaves are used as fertilizers. The oil that comes out from its seed is edible and is known as sal butter. It is often used in cooking and for burning oil lamps. The seeds of the sal tree are used for fat extraction. Its oil is even used for adulterating ghee. An adivasi marriage cannot be solemnised without sal leaves as people give marriage invitation in the form of folded sal leaves, with bit of turmeric and rice inside it.

The sal resin is an equally important product, it is an aromatic secretion that is used as a component in incense sticks. It is also used as a medicine. The resin is used in the indigenous system of medicine as an astringent and detergent and is usefful in diarrhea and dysentery. Industrial use of sal resin is also varied; it is used as an ingredient of ointments for skin care and its oils are also used for making herbal ear drops.

Sal resin attracts an insect called the sal heart wood borer (Verma 2105). Resin secretion increases as the infestation of this insect increases. The resin is secreted as a defensive response to the infestation. The tree drowns the larvae in their tunnels by exuding resin and drowning 85 to 100 per cent of the larvae (Verma 2015). But the excretion of resin weakens the tree, making it more susceptible to subsequent attacks. Hence, when the larvae attack in large numbers and the points of attack are numerous, the tree cannot produce resin in sufficient quantity and succumbs to the attack. This outflow of resin forms the very obvious and familiar yellow trickle (ral) seen in most sal forests (Verma 2015). The ral dries on the bark which is later collected.

Lac resin

It is said that Lac is the oldest form of resin known to humankind. As the last week of November passes, making way for the early days of winter, villagers who own kusum, ber and palash trees start scrapping matured encrustations of stick lac from their trees. In Chhattisgarh this coincides with the harvesting season of paddy. Most of the lac which is sold by the villagers at the local haats provides them with the necessary cash to hire hands for harvesting their crop. With reciprocational exchange of labour slowly being replaced by wage labour; the quick cash from lac becomes essential for people to harvest their food crop.

Stick lac is a resinous encrustation, formed around the bodies of tiny female lac insect by its own secretions and excretions after it has been cultured on the barks of lac host trees, the most important of which are kusum, ber and palash. The resinous secretion which is known as stick lac contains about 4-5% wax and 1% water-soluble colouring material known as lac-dye (laccaic acid).

Lac resin is produced by an insect called Kerria lacca. The resin had limited usage in the adivasi life and were only used sparingly to seal pots, pans and bhurkas but as soon as the industrial world discovered the rearing potential of the central Indian forests lac became a cash crop reared by the villagers. Lac as a resin became an economic lifeline for a significant number of forest dwelling communities as they historically started interacting with industrial modernity. Lac rearing supplements the primary occupation of the forest dwellers as cultivators, rearers and gatherers of forest produces. Two different strains of this species, the Rangini and the Kusumi contribute nearly 95% of the total lac production of the country. While kusum and ber can host the kusumi variety of lac insects, palash can host the rangini variety of lac. Kahir, babul and arhar trees can also host different strains of the lac insect but are not commercially viable. The rangini strain doesn’t thrive on kusum (Schleichera oleosa) but performs well on other host plant species. It is a bivoltine strain having four months (rainy season) and eight months (summer season) life cycle. The kusumi strain on the other hand has a more or less two-equidurational life cycle in a year and prefers kusum (Schleichera oleosa) for production of light coloured resin of superior quality with respect to life and flow.

Sher Singh Anchala, a Gondi scholar and a lac rearer himself shared that he grew up observing his family rear lac. According to him in the pre-industrial era gatherers would collect them whenever they required natural adhesive, they did not culture it artificially, as the need was limited. Modern industrial demand introduced artificial innoculation of the insects on their host plants.

However, a brief survey of literature also suggests that urban civilizations of antiquity had been aware of culturing lac artificially. Artificial innoculation and commercial application of lac also has a long history dating back to the Indus valley era; later during the Mughal era European monarchs had also sent various research contingents to the subcontinent to study the resin generating insects. Vedic and vedantic texts also mention lac (Mandal 2014). Modern scientific study of lac started much later. In 1709 Father Tachard discovered the insect that produced lac. First of all Kerr (1782) gave the name Coccus lacca which was also agreed by Ratzeburi (1833) and Carter (1861). Later Green (1922) and Chatterjee (1915) called the lac insect as Tachardia lacca (kerr). Finally, the name was given as Laccifer lacca some also call it Kerria Lacca (Samiksha).

Kusmi Lac and Bastar

Bastar is known for its kusumi lac, it amounts to approximately 16 per cent of the national average (Yogi. et al 2105). The forests of south Bastar, especially the Kangar Valley national park region, adjacent regions of Jagdalpur, Dantewada, Konta are rife with kusum trees. In the southwestern part of Chhattisgarh such as Bijapur, forests of Narayanpur, bade dongar, chote dongar, abujh marh are also rife with kusum trees. Bhanupratappur, Kanker, Keshkal and Kondagaon tehsil are also lush with kusum. An ICAR and IINRG report iterates that less than 5 percent of available host plants are actually used for lac cultivation.The forests of Bastar have huge potential for culturing and rearing lac. Even in its current state Korba followed by Kanker district leads in production of kusumi lac. All the processing units of Dhamtari processes lac that comes largely from Kanker followed by Keshkal and other southern districts. In Dhamtari stick lac is converted to commercial grades of seed lac and then shellac. The yield of processed lac from stick lac varies between 40-60% depending on the host tree, area of cultivation and other factors. Apart from lac resin, stick lac contains 6-7% of lac wax, 3-5% of water moisture, colouring matter (lac dye), and impurities like insect debris, wood pieces, sand etc. The refinement of stick lac into seed lac is mostly carried out in cottage scale or in semi mechanised factories. After refinement, seed lac is converted to shellac by hand-made or machine-made process.

Most of the lac produced in Bastar makes it way out of the country via the port of Kolkata as almost all of it gets exported to USA, Switzerland, Germany and other European countries (Yogi et al 2015). The international trade of lac is monitored by Shellac and Forest Products Export Promotion Council (SHEFEXIL). Lac is an essential component in a host of industrial products ranging from pharmaceuticals, electronics, sealants dyes, paints and polishes.

Conclusion

Before the article is drawn into a conclusion I must re-emphasize that all the above mentioned resins and saps are commonly observed, there are many similar gums and resins which are collected from the forests of Bastar most of them are nationalized Non-timber Forest Produce (NTFP) and only the forest Department has the monopoly to trade them. Since lac does not fall into that category we have a whole chain of traders and processors who are involved in adding heavily to the afterlife of such a resin that comes out of the interaction of a host of trees, insects and humans.

On the end of the forest dwellers most of the gathering activity still functions as a secondary activity given that the primary occupation of the winter season being wage labour, landscaping, logging and building- (repairing of houses, bridges, check dams and fences.) All these activities remain punctuated with various community festivals, fairs and celebrations. Life in Bastar is weaved with the products of the forests. There can be no festivals, no fairs no life without ral

References

EPW.“Bastar: Development and Democracy” Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 24, No. 40 (Oct. 7, 1989), pp. 2237-2241.

URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4395427

Sivaramakrishnan, K. Modern Forests: Statemaking and Environmental Change in Colonial Eastern India. Stanford University Press, 1999

Mandal, J.P & Sarkhel, J. Analysis of Cost Effectiveness of Lac Processing in Purulia District. Business Spectrum, Vol.4, No.2 (Jul-December 2014).

URL: http://admin.iaasouthbengalbranch.org/journal/8_Article5.pdf

Mandal J, P. “A study of Problems and Prospects of Lac Industry in Purulia, District West Bengal” submitted to Burdwan University, West Bengal.

URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10603/121488

Yogi. R.K et al. Lac, Plant Resin and Gum Statistics 2014: At a Glance. ICAR-Indian Institute of Natural Resins and Gums (IINRG), 2015

Ramnath. M. Woodsmoke and Leafcups: Autobiographical footnotes to the anthropology of the Durwa. Harper-Collins, 2105

Samiksha, S. Lac-insect for Lac Culture in India: Life Cycle of Lac-insect (with pictures). http://www.yourarticlelibrary.com

Verma, J. Eaten Hollow. Down to Earth. June, 2015

URL: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/coverage/eaten-hollow-21190

This content has been created as part of a project commissioned by the Directorate of Culture and archaeology, Government of Chhattisgarh to document the cultural and natural heritage of the state of Chhattisgarh.