In this thought-provoking essay Prof. H.S. Shivaprakash posits the possible limits of rasa aesthetics by brilliantly analysing its realms of influence and mode of transforming meaning, particularly in theatre. The scholar-teacher-translator writes, ‘…the way rasa gets transformed through retellings and re-enactments of inter-semiotic translation, from literature to theatre, for instance, has never been interrogated…’ He chooses as exemplars Mahasweta Devi’s epochal short story ‘Draupadi’ and, from theatre, Kanhailal’s disturbing and powerful ‘Draupadi’, about which the lead actress Sabitri states, ‘… incarnates resistance through the being of an actor on the stage that is capable of disturbing the audience deeply, instead of teaching it.’ An exhilarating read.

1

The transformations that take place in the course of inter-semiotic translation when one genre, say literature, is translated into another, say theatre, opens up several important issues. The change of the genre for one thing, also brings about shifts in meaning. Though such shifts have been addressed from different perpectives, the shifts taking place in the inmost core of the artwork is rarely examined. The in-most core of theatre according to Bharata is ‘Rasa’. Though later, the rasa of non-theatrical genres like poetry was avidly debated, it was done only in the context of communication of particular art work. But the way rasa gets transformed through retellings and re-enactments of inter-semiotic translation, from literature to theatre for instance has never been interrogated. The intricacies of how the art work impacts, it seems to me, needs to be approached from perspectives different from the established ones. These are the questions which I would like to address in this essay. A great deal of available scholarly material both by theory and practice people on the topic of literature and theatre, or, alternatively, text and performance hinges around a small cluster of ideas – a) the relationship between pre – - written play texts and performances based on them, i.e., about how close or apart they are; b) how socio-political contexts impact and shape performances and receptions; c) how performance as a practice, independent of text, can become an intervention in the way things are, i.e. politics of performance: class/caste/gender/race etc.

The diverse stories of the two-way journey through text – performance – society has engaged scholarly enquiry in explorations, first, of theatre criticism and, now of performance theory. Some of the script-centred approaches, while trying to escape the tyranny of the text, restore, after seeming rebellion, the same tyranny by considering the performance also to be a text. Also, by focusing too much on representational aspects of texts and performance they ignore the transitive dimensions of these practices in relation to the living space beyond texts and performances, which of course impacts and is impacted by these practices.

I would like to approach the area from a different perspective from those adumbrated above. My approach is certainly not that of a knowing person but that of a doing person because of my passionate involvement in writing, staging, teaching and living drama and theatre.

As an alternative to the existing model of isolating specific texts and performances from each other and contexts, I would propose the following model: texts (mental/oral/literary/cyber) loop into performances (ritual/theatre/music/festival/painting/sculpture/architecture) which further loop into real life actions (social/political/economic etc). I find the concept of orature coined by Ngugi wa Thiong’o(1998) extremely useful for this purpose. Orature, unlike orality as opposed to Literature, according to Thiong’o (1998) , is the cultural substratum of a whole range of practices and expressions such as myth, ritual, festival, folktale, proverbs, jokes, literary genres, theatrical performances, cinema, and, of late, cybertures. The translation of a text (literary or otherwise) is a small but very fascinating loop in a non-linear, multi-layered process of mutually impacting loops. Put another way—these unending processes of inter-looping involve endless chains of re-tellings, re-enactments, re-livings, of an original lost forever but is retrieved only in re-enactments. When repetitions are not just repetitions, they create something new, a new surplus of meaning and break out of rituals of repetitions. This goes beyond Mikhail Bakhtin’s (1984) concept of literary traditions as examples of indirect speech and that of carnivalisation. Like a Mobius strip, such re-inventions go beyond a single tradition (literary/cultural) and beyond the hitherto accrued significances.

Though this model, I believe, can explain the working of any cultural practice, in order to be specific, I would like to focus on one of the most powerful productions of recent Indian theatre: Kanhailal’s Draupadi.

2

The molestation of Draupadi is a well-known episode in the Mahabharata. Let us brush aside the convenient view that a certain Sanskrit version of the story is the original text and that all other versions are its translations. If one considers the bewildering versions of the Mahabharata in tribal, folk, classical, Bhakti and modern traditions, it is useful to consider the Mahabharata as an illustration of what Thiong’o has called orature. This orature imbues textual practices (legends, proverbs, jokes, folktales, poems, comics), rituals, performances, the arts and contemporary cultural practices (cinema, TV, cyberture).

The Draupadi episode has haunted the imagination of the subcontinent for centuries. It is the archetype of innumerable rapes in human history, which are the recurrent inputs for imaginative explorations. Though Draupadi’s molestation does not culminate in an all-out rape in most of the versions of the Mahabharata, including Vyasa’s, several versions have tried to rationalise it away in several different ways. The Bhagavata versions did this by inventing a deus ex machina in the form of Lord Krishna’s timely divine intervention by bestowing on the victim numberless sarees which left even the tireless villain Dushasana exhausted. A Kannada version of the episode in the oral Mahabharata of Hakkipikke tribes rationalises it by avoiding the molestation. In this version, after Pandavas lose the game of dice, Draupadi takes over and defeats all the Kauravas and sends them to exile. Vyasa himself leaves the terrible episode inconclusive. Draupadi appeals to the wisest character of the story, Bhishma, and asks: ‘“Is this dastardly act in keeping with Dharma?’” For a long time even the most eloquent Bhishma is at a loss for words. At last he works out a strategy of rationalisation: ‘“According to dharma, your husbands have lost the game and become Kauravas’ slaves. Because, according to dharma, you are the slave of your husbands, who are now Kauravas’ slaves, they can do what they like with you.’” Later all the worthy courtiers listen to the hooting of owl —a frighteningly bad omen. Kauravas are then too scared to go ahead with their heroic rape.

3

Draupadi’s cries of protest have continued to resonate in Indian literature, theatre and arts all down the ages right up to modern times. The great Tamil poet Subrahmanya Bharatiyar wrote a poetic play Panchali Shabatham modelled on Tirukoottu during the days of colonial struggle. She becomes Mother India being molested by the British. Though Lord Krishna appears well in time to save her honour, the emphasis of the play is on Draupadi’s vow to avenge the perpetrators of her humiliation. This play, also popular with Bharatanatyam dancers, has been performed in dance also. This was a historic intervention into the retellings of the episode because of inscribing into the story a new political meaning— the protest against colonial exploitation. This is how Bharatiyar creates a meaning in excess of those already built into the traditions of reworking the episode.

4

Draupadi’s cries of protest continued to haunt Indian imagination even after Bharatiyar’s ‘Draupadi’, Mother India, freed herself from the stranglehold of his Kauravas, British colonisers. Many daughters of Mother India, particularly from underprivileged sections— dalits, tribals and the poor— continue to be raped; no Krishna appears in time to rescue them.

One such daughter is Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi, the protagonist of a short story written in 1978 subjected to a brutal rape. This story has a denouement different from the earlier narration. Having reached the utmost bounds of humiliation, Draupadi hits back at the rapist. Instead of trying to cover up her nudity, she thunders at the rapist: ‘“What’s the use of clothes? You can strip me but how can you clothe me again? Are you a man?’” When Draupadi, who was only molested, is reborn in Mahasweta Devi’s short story, she is not only raped but turns her hurt body into weapon to terrorise the rapist male.

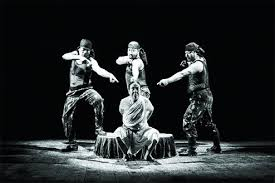

Fig. 1: A still from a staging of Kanhailal's 'Draupadi'

Again the archetype jumps out of the usual chain of re-workings in which the victim is left shattered and the victor’s nemesis is either delayed or deferred forever or punished only with the intervention of invisible powers.

The victor gets his due if the victim survives the victimhood and hits at him like a trampled serpent.

5

If we follow Draupadi’s cries for help, we also begin to hear the boastful guffaws of victorious rapists. We then begin to listen to them and then resonate with it. It is during this process that unprecedented versions of the same story told afresh emerge. We have seen how new nuances entered the story when Bharatiyar and Mahasweta Devi chose to rewrite it. It was not just a matter of re-reading or re-interpretation. It involves the discovery of new synchronisations within and without. Draupadi, an archetype, also becomes a possibility not contained in earlier versions. Bharatiyar finds the archetypal molestation coeval with the coloniser’s onslaught whereas Mahasweta Devi synchronises it with state atrocities on the oppressed. Bharatiyar’s Draupadi ends up taking an oath for revenge. Mahasweta Devi’s Draupadi seizes on the very moment of rape to hit back at the perpetrator, making her victimised body into a potent weapon to crush and silence the oppressor, transcending her victimhood.

How did Kanhailal stage this?

6

What Kanhailal has done is to do consciously what other stage adapters try doing unconsciously and never quite succeeding. Just as Mahasweta Devi brings in a new denouement not contained in the sources and which is synchronous with socio-political violence in those times, Kanhailal presses the archetype into the service of rape victims in Manipur who free themselves from shame and victimhood. His Draupadi’s molested and raped body becomes, through the agency of the actress Sabitri’s immensely expressive body, the site of such atrocities and of liberation from it here and now. For Kanhailal’s theatre is the theatre of here-and-now and of synchronicities. In a most liberating moment of Indian theatre, the actress turned into Draupadi turned into Manorama and other rape victims turned into the mutilated body of Manipur, bares herself and employs her nudity as a means to unnerve and terrorise the male conqueror. This was, like all moments of honest self-knowledge, a very disturbing moment. It exposed to public view a wound and an ache so painful and shameful that the public always avoids admitting and focusing on it.

Fig. 2: A still from a staging of Kanhailal's 'Draupadi'

Let us listen to how Manipur responded to it in the words of the actress who healed this wound by embodying it on stage. Says Sabitri in an interview with Debasis Majumdar:

“The consequence of the production of Draupadi had two contradictory reactions in Manipur. One group was in favour of the nudity that could create a new sense of resistance, which is still necessary in response to the dominant tensions in Manipur that include an excessive misuse of the female sex as a strategy for repression. The other reaction, mainly from women, was that Sabitri’s nudity was a shameless act, hurting the local sensibility of Manipuri women. It was terribly condemned by this faction. The confrontation between the two groups continued daily, each focusing its own views, contradicting the other, in all the local newspapers for more than a month. It was in 2000. Even our friends opposed us and asserted that Draupadi was not political drama. Kanhailal, obsessed with sex, allowed Sabitri to go nude onstage, was one of the arguments given against the performance. We kept quiet in response to all these harsh views and opinions. This situation confirmed our belief that Draupadi might not be political drama as per their academic knowledge, since ours is the kind of political theatre that does not obviously assert ideology, but incarnates resistance through the being of an actor on the stage that is capable of disturbing the audience deeply, instead of teaching it.

Draupadi, as a work of art, reacts ahead of the time as we also find in Pebet and Memoirs of Africa. Pebet was created in 1975, but it is still alive. It could foretell what would happen in the future, nearly thirty years later. Draupadi, too, became a premonition of what happened in 2004, after five years of production. The day after the twelve women’s naked protest in Imphal, the local paper highlighted that Kanhailal’s Draupadi was acted out in real life. Some of the articulate opponents reversed their opinion and glorified both Kanhailal and Sabitri. The hearsay continued in Manipur that Oja Kanhailal is the chingu (the wise man who can predict the future). We were neither affected by all the controversies, nor by the glorification. We continue to remain as we are.” (2016: 189-194)

Sabitri, who, like her husband Kanhailal, rejects ideological theatre in favour of a theatre that ‘incarnates resistance through the being of an actor on stage that is capable of disturbing the audience deeply, instead of teaching it.’ This incarnation was also a premonition. The history of recurrent rapes of the region and the nude protest in the future became synchronous with the stage enactment of Draupadi.

Because Kanhailal’s theatre goes beyond the conventions of traditional theatre that illustrates techniques, and modern theatre that illustrates ideologies, political and aesthetic, and aims at producing, like a ritual, a sensory and a psychic effect on the spectator, it not only disturbed the public but became a prototype for nude protesters for years later. It is not that the protesters watched the play before protesting. But the director and the actor had the fore-knowledge. Thus the production became a Mobius strip being part of and at the same time jumping out of the loops of repetition.

My conclusion is a beginning: part of the loop and also Mobius strip. Staging a text is part of the genealogy of re-writing not of an original but an original in the sense of having no precedents. The text content is also dynamic, being a process of a series of re-telling and re-writings in changing historical conditions. Most of them are just repetitions but only a few bold imaginative acts of incarnating the given along with the new experiential content.

7

My own understanding of the processes of inter-semiotic translations has emphasized the non-linear aspects. This also resonates with the word actually used by Sabitri in the above interview- incarnations, which cuts through the before-and--after relationships of events.

Rasa, among other things, connotes a phenomenon that is non-linear and synchronous. Let us recount the way Bharata sums up rasa production as something that comes about thanks to the combination of Vibhava (causal factors), Anubhava), Anubhava (the concomitant involuntary responses) and Sancharibhavas (the voluntary responses). What undergoes these changes is Bhava (the archetypal emotions), dominant in the work, for instance, Rati (the erotic emotion) is transformed by the above process into aesthetic essence Shringara.

How does it work out in the context of retellings and re-enactments of molestation of Draupadi culminating in Kanhailal’s play?

We have noted the new significations that emerge in the production. The significances predicated upon linear temporality of history. In every leap out of cycle of repetitions, the hither to un-thought-of meanings emerge.

A similar emergence of a new phenomenon cannot happen in the rasa effect because rasa, by nature, like bhavas that produce them are only finite in number. According to Bharata they were only eight. However great a leap of an individual artwork from cycles of repetitions, there cannot be the emergence any first time rasa as in the case of meaning. All that happens is confined to the transformation of one rasa into another provided the new theatrical is able to employ different sets of vibhavas and anubhavas.

Fig. 3: A still from a staging of Kanhailal's 'Draupadi'

To my mind, Mahasveta Devi’s short story and then more emphatically Kanhailal’s stage re-enactment of Draupadi replaced Karuna Rasa (compassion) resulting from Shoka (sorrow) from Draupadi’s victimhood in earlier texts and performances by Rudra Rasa (furry) resulting from new Draupadi who jumps off the cliff of sorrow into the seething ocean of furry.

The possibility of meanings can thus accommodate unprecedented ones but transformational rasa happens only within the framework of a finite number of rasa.

References

Bakhtin, Mikhail Mikhaĭlovich. 1984. Rabelais and Hhis Wworld. Vol. 341. Indiana University Press.

Majumdar, Debasis, 2016. Theatre of the Earth: The Works of Heisnan Kanhailal. Calcutta: Seagull Books.

Thiong'o, Ngugi wa. 1998. Penpoints, Ggunpoints, and Ddreams: Towards a Ccritical Ttheory of the Arts and the Sstate in Africa. Clarendon Press, 1998.