Prize-winning translator from Hindi, Philip Lutgendorf offers insights into his pet passion: commercial Hindi cinema, better known as Bollywood. This industry has successfully withstood the onslaught of Hollywood for decades, a feat no other national film industry has pulled off with as much panache. In a globalised world Bollywood is dearly beloved and synonymous with long, loud, entertaining song-and-dance movies. Professor Lutgendorf takes off from renowned translator A.K. Ramanujan’s playfully titled essay ‘Is There an Indian Way of Thinking?’ to artfully deconstruct the components of these masala films and their unique interpretation of rasa theory.

Fig. 1: Nation as narration: the Subcontinent speaks in the framing narrative of K. Asif’s ‘historical’ masterpiece Mughal-e-Azam (‘the great Mughal,’ 1960).

‘…the Hindi film appears to be perhaps the most powerful cultural product based on non-Western aesthetic principles presently alive…’[i]

‘The difference between Hindi and Western films is like that between an epic and a short story.’ Screenwriter Javed Akhtar[ii] Poet and polymath A.K. Ramanujan once wrote a serious essay that he playfully titled, ‘Is There an Indian Way of Thinking?’ It began by querying its own question, for Ramanujan was aware of the risk of essentialism (and its past deployment by orientalists, Marxists, nationalists, etc.) when approaching a vast region of perhaps greater ethnic and linguistic diversity than Europe.[iii] Yet as a trained linguist and folklorist, he was indeed interested in the recurring patterns and themes that lend a distinctive flavour to South Asian culture—a flavour that may be especially recognisable to an outsider, or to an insider who steps out. That Indian popular films likewise have a definite ‘‘flavor’’ is generally recognised (and one indigenous descriptor of them is indeed as masala or ‘‘spicy’’), even by Anglo-Americans who encounter them while surfing cable TV channels—and not simply because the actors happen to be Indian. The films look, sound, and feel different in important ways, and a kind of cinematic culture-shock may accompany a first prolonged exposure. A distinguished American film scholar, after viewing his first ‘‘masala blockbuster’’ in the early 1990s, remarked to me that the various cinemas he had studied—American, French, Japanese, African—all seemed to play by a similar set of aesthetic rules, ‘‘…but this is a different universe.’’ Experienced viewers are familiar with the sometimes negative responses of neophyte visitors to this universe: the complaint that its films ‘‘all look the same,’’ are mind-numbingly long, have incoherent plots and raucous music, belong to no known genre but appear to be a mish-mash of several, and are naive and crude imitations of ‘real’ (i.e. Hollywood) movies, etc.—all, by the way, complaints that are regularly voiced by some Indians as well, particularly by critics writing in English. They also know that millions of people, including vast audiences outside the subcontinent, apparently understand and love the ‘difference’ of these films.

Ramanujan published his essay in the anthology India Through Hindu Categories (Marriott 1990), which was part of a broad, if sporadic, effort within the Euro-American academy, spurred by post-World War II interest in ‘area studies,’ to understand other cultures in their own terms, and to acknowledge the assumptions rooted in Western intellectual tradition that had unconsciously biased previous inquiries. For South Asia, the standard narratives of history, religion, and literature had largely emerged from the colonial-era collaboration of British and Indian elites; given the asymmetry of power in this collaboration, the expectations of the former often influenced the information they received from the latter, which in turn shaped the explanatory narratives they crafted and then (through the colonial knowledge economy) exported back to their native subjects. Despite recent efforts to question or deconstruct the received narratives of ‘Hinduism’ (as a monolithic ‘religion’[iv]), ‘caste’ (as a rigid ‘system’ and distinctively Indian form of social organisation[v]), and even language (in the case of Hindi and Urdu, as reified and religion-specific[vi]), scholars still remain far from the goal of ‘provincializing Europe’—turning the lens back on the ostensibly all-seeing eye of Euro-American intellectual hegemony[vii]. In film studies, a long-reigning Copernican discourse on ‘cinema’ in general (i.e., American, and to a lesser extent, European), occasionally digressed to consider ‘national cinemas’ as represented by a few auteurs. India was associated with the Bengali ‘art films’ of Satyajit Ray, with an occasional bemused reference to ‘the lip-synched Bollywood musical’[viii]—a designation that airily dismisses tens of thousands of feature films produced since the advent of sound in 1931. That this enormous and influential body of popular art is now receiving scholarly notice suggests the need for, at least, systemic realignment (as when a big new planet swims into our ken); a more audacious suggestion is that its ‘different universe’ might make possible an Einsteinian paradigm-shift by introducing new ways of thinking about the space-time of cinematic narrative.

That is, of course, if the universe is truly ‘different.’ Assertions of the distinctive ‘Indianness’ of Indian popular cinema—or its lack—have emerged from a variety of scholarly approaches,[ix] viz.:

- Cultural-historical – this traces the distinct features of Indian cinema to older styles of oral and theatrical performance, some of which survive into modern times. A fairly standard genealogy cites the ancient epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, classical Sanskrit drama, regional folk theatres of the medieval-to-modern period, and the Parsi theatree of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[x]

- Technological – here the distinctive features of Indian cinema are traced to the advent of technologies of image reproduction during the second half of the 19th century, resulting in the rapid evolution and dissemination of a common visual code for theatrical staging, poster art, cinema, comic books, advertising, etc.[xi]. A related approach, confined to cinema itself, analyses camerawork and sound, noting Indian filmmakers’ rejection of the ‘invisible style’ and ‘centering’ principle of classic Hollywood in favour of an aesthetic of ‘frontality’ (especially in early ‘mythologicals’), ‘flashy’ camerawork, and a consciously artificial style, further heightened by the use of non-synch sound and ‘playback’ singing[xii], as well as the profligate insertion of ‘interruptions’ in linear narrative[xiii].

- Psychological/mythic – this approach reads popular films as ‘contemporary myths which, through the vehicle of fantasy and the process of identification, temporarily heal for their audience the principal stresses arising out of Indian family relationships’[xiv]. The favoured approach is psychoanalytic[xv], although there has been one ambitious attempt to use a ‘mythological’ film to modify a basic Freudian paradigm with respect to Indian culture[xvi].

- Political-economic – this approach, drawing on the Marxist-influenced critical social theory of the Frankfurt School, attributes the distinctive features of Indian popular cinema to the material and socio-political conditions of 20th century India and of the film industry itself, and argues that the films encode an ideology that ‘subsumes’ a modernist agenda of egalitarianism, individualism, and radical social change within a feudal and non-egalitarian status quo[xvii]. Other similarly ambitious surveys see popular films as essentially allegorizing the political history of the nation-state[xviii].

These approaches are neither exhaustive nor incompatible; many scholars combine two or more. Thus it is fairly common to invoke the first by way of sketching a cultural background, and then to proceed to one or more of the others, perhaps analysing a single film in their terms[xix]. At times, however, there is an element of antagonism between proponents of the first and fourth approaches. On the one hand, one encounters grandiose claims that the classical tradition and especially the two Sanskrit epics constitute ‘the great code’ of popular filmmaking, and that ‘any theoretical critique of Bombay cinema must begin with a systematic analysis of the grand Indian meta-text and “founder of Indian discursivity,” namely the Mahabharata/Ramayana’[xx]. This is a claim that is sometimes made by filmmakers themselves, as when Mumbai director Dharmesh Darshan tells an interviewer, ‘In India, our stories depend on the Ramayan—all our stories are somewhere connected to this holy book’[xxi]. On the other hand, a Marxist scholar criticises ‘anthropologists and Indologists or others employing the tools of these disciplines’ for their tendency ‘to read popular cinema as evidence of the unbroken continuity of Indian culture and its tenacity in the face of the assault of modernity’[xxii]. He warns that such ‘eternalist proclamations…while claiming to reveal the truth about Indian cinema, actually contribute to the maintenance of an Indological myth: the myth of the mythically-minded Indian’[xxiii].

In what follows, I use my training as a folklorist and student of oral performance and popular narrative traditions to revisit the first approach cited above, but I do so mindful of the criticisms just offered. I have no wish to contribute to what Kazmi calls ‘the fetishization of tradition’[xxiv], to suggest that there is an unchanging ‘essence’ of Indian performance, or to imply that some genetic inheritance predisposes South Asians to relish three-hour spectacles of music, dance, and high emotion. Such tastes reflect nurture, not nature, and they, and the films that cater to them, are influenced by diverse forces that also change over time. The claim that popular films are all based on epic archetypes is demonstrably groundless, as is the hyperbolic (and insulting) generalisation that they reflect folk traditions ‘…that impinge on the Indian’s psyche and never allow him to escape from the psychological parameters of being an Indian villager’[xxv]—an assessment that reduces a population of 1.3 billion (increasing numbers of whom now live in urban areas) to (male) embodiments of an inescapably rustic ‘Indian psyche.’ But the Marxist reduction is equally unsatisfying: M. Madhava Prasad’s argument for the decades-long dominance of a single ideological master narrative hinges on a few roughly-sketched plot outlines, omits questions of reception, and ignores the films’ poetic and musical component altogether[xxvi].

The practices and conventions that I will be discussing are observably pervasive of the South Asian cultural environment, alluded to in verbal idioms, body language, and ubiquitous iconography. Hence they can be relearned by successive generations, though their precise forms at any given moment are naturally subject to historical contingency and outside influence. Indeed, the ‘hybridity’ of Indian popular cinema is another of its proverbial features: its pastiche and parody of foreign forms and practices and its frequent borrowing of camera shots, plot ideas, and musical styles. Although every cinema borrows, the specific forms that borrowing assumes in the post-colonial South Asian context and the economic and cultural forces that influence it are indeed deserving of study. Here I will only propose that the visual and musical hybridity of this cinema has itself become, like other ingredients in its overall masala mix, one of its distinctively ‘Indian’ features—identifying it as, in Anil Saari’s words, ‘an eclectic, assimilative, imitative and plagiaristic creature that is constantly rebelling against its influences…’[xxvii].

Rosie Thomas observed that ‘films are in no sense a simple reflection of the wider society, but are produced by an apparatus that has its own momentum and logic’[xxviii]. She thus underscored the power of cinematic conventions, whatever their genealogy, to rapidly become self-perpetuating, serving to educate both audiences and producers in the expectation of what a film ought to be. Since the makers of commercial films constantly strive to fulfill audience expectations, it may well be true that the single biggest influence on Indian popular cinema has long been — Indian popular cinema. Yet it is equally clear that the distinctive conventions of this art form, which have tenaciously resisted the influence of Western cinemas, did not arise in a cultural vacuum.

In the sections that follow, my aim, first of all, is to give novice students of Indian popular cinema an acquaintance with some of the terms, texts, and narrative genres that are regularly cited in studies of its cultural origins, along with references to relevant primary and secondary sources. In addition, I seek to correct certain imbalances and omissions in the standard genealogical narrative as outlined earlier, by presenting material (e.g., on the Indo-Islamic romance tradition) that has been omitted by other scholars. Finally, I aim to suggest ways in which selected resources drawn from the Indian cultural heritage might be applied not only to the study of Indian cinema (as an exotic ‘other’ to Western cinemas) but more broadly to the study of cinema in general.

Seeing

Fig. 2: Unveiling the beloved: Waheeda Rahman as a Muslim bride seeing (and being seen by) her husband for the first time, in Mohammed Sadiq and Guru Dutt’s Chaudhvin ka Chand (Full Moon, 1960).

Academic scholarship took more than half a century to begin to look at cinematic ‘looking,’ and indeed at cinema itself as a subject of serious inquiry. The delay may have reflected not merely the inertia of disciplines, but a more ingrained prejudice toward text over image traceable at least to the Protestant Reformation and the so-called Enlightenment. The subsequent proliferation of ever more sophisticated technologies for the reproduction of images was experienced by some scholars as a worrisome onslaught on the cerebral realm of verbal discourse, which may explain why film studies as a discipline initially arose as an offshoot of literary criticism, accommodating film as another form of ‘text.’ As Prasad points out, the development of critical vocabulary for analysing the visual aspect of film (such as the concepts of ‘male gaze’ and ‘scopophilia’[xxix]) has tended to assume an essentially ‘realist’ cinema whose spectator ‘occupies an isolated, individualised position of voyeurism coupled with an anchoring identification with a figure in the narrative’[xxx]—an assumption that is problematic when applied to Indian commercial films. A yet more holistic appreciation of the cinematic experience remains a challenging agenda, and sound and music continue to be relatively neglected in scholarship. As I will note shortly, this intellectual genealogy may be contrasted with an Indian synaesthetic discourse, dating back some fifteen centuries, which is based squarely on visual and aural performance.

Vision and sound already interact in the hymns of the Rigveda (ca. mid-second millennium B.C.E.), attributed to poets known both as ‘singers’ (kavi) and ‘seers’ (rishi), who were credited with the ability to ‘see’ the gods as well as the ‘sound-formulas’ (mantra) of the hymns, suggesting a blurring of the senses in mystical experience. Rishi, conventionally translated ‘sage,’ comes from the Sanskrit verb root drish, which has a double meaning also found in comparable verbs used in modern Indian languages (e.g., the Hindi verb dekhna): it means both ‘to see’ (passively) and ‘to look at’ (actively). Indeed, ‘seeing’ was and continues to be understood as a tangible encounter in which sight reaches out from the eyes to ‘touch’ objects and ‘take’ them back into the seer (hence dekhna is normally compounded with lena, ‘to take,’ also used for verbs of oral ingestion). Likewise derived from drish is the noun darshan, ‘seeing, looking at,’ a term that assumed great importance following the decline of the Vedic sacrificial cult and the rise, during the first millennium of the Common Era, of the worship of gods embodied in images.

The iconic prolixity of Hinduism is a commonplace. There are often said to be ‘three hundred and thirty million gods,’ and their representations typically bristle with supernumerary heads, arms, and weapons. A shared and striking feature of the deities is their eyes, often huge and elongated, which gaze directly at the viewer. The theo-visual spectacle of the Hindu pantheon was, however, ‘hard to see’ for most European observers prior to the 20th century, and they dismissed it either as ‘demonic’ or as a distorted simulacrum of the ‘realist’ aesthetic of Greco-Roman civilization[xxxi]—the latter assessment prefiguring one common Western response to the visual code of Indian popular films. When Hindu images are crafted, their painted or inlaid eyes are customarily added last and then ritually ‘opened’ in a ritual inviting the deity into the icon and making him or her available for the primary act of worship, which is ‘seeing/looking’ (darshana; Hindi darshan). In Indian English, people go to temples ‘to take darshan’; Hindi usage favors ‘to do darshan’ (darshan karna)—both idioms imply a willful and tangible act[xxxii]. ‘Darshanic’ contact invites the exchange of substance through the eyes, which are not simply ‘windows of the soul,’ but portals to a self that is conceived as relatively less autonomous and bounded and more psychically permeable than in Western understandings[xxxiii]. Darshan may also refer to the auspicious sight of powerful places and persons—holy people and kings (and politicians and filmstars) ‘give darshan’ to those who approach them.

The derivatives of Sanskrit drish do not exhaust the vocabulary of seeing in South Asia. The word nazar (‘look’ or ‘glance’), imported from Arabic and Persian, has similar connotations of tangible exchange and is common both in everyday speech (where it figures in a large number of idioms) as well as in Indo-Islamic religious discourse. It is applied to the eye contact of lovers, especially the first sight that arouses passion, and also to the beneficent gaze of Sufi masters, which watches over and blesses their disciples. A similar range of meanings is conveyed by idioms using the Persian-derived nigah, which translates as ‘look’ or ‘glance,’ yet connotes a more potent contact than these English words. It also connotes, in the context of a culture that idealised (and sometimes practised) the veiling of respectable women, an illicit glimpse that can give rise to intense ‘love at first sight’ that is disruptive of social and familial conventions and hierarchy. Another potentially dangerous side of sight—when negative feelings or forces exit or enter through the eyes—is also invoked through idioms of a ‘black’ or ‘evil’ gaze (kali nazar, bura nazar) from which one seeks protection. Such looks are associated with powerful and proscribed desires—especially lust, envy, or covetousness.

The ideology and practice of darshan/nazar has contributed to a cinematic aesthetic of ‘frontality,’ especially in early mythological films that recapitulated the conventions of poster illustration: the deity/actor, often centrally framed within a static tableau, was positioned to invite sustained eye contact with the viewer[xxxiv]. It likewise contributes to the more ubiquitous fetish, across all cinematic genres and periods, for close-ups of eyes and glances, especially in scenes between lovers,[xxxv] as well as the great emphasis (also notable in Indian dance, folk theatre, and miniature painting) on the eyes as communicators of emotion (e.g., the popular 1970s and 80s technique of repeated facial zoom shots, locking on the eyes, during moments of high emotion). But there is more to cinematic ‘seeing’ than this, since darshan is a ‘gaze’ that is returned. In a crowded Hindu temple, one can observe worshippers positioning themselves so that their eyes have a clear line of contact with those of the god. Their explanations emphasise that they do not merely want to see the deity, but to be seen by him/her so that the deity’s powerful and unwavering gaze may enter into them. I have sometimes translated darshan as ‘visual communion,’ but ‘visual dialogue’ or ‘visual intercourse’ might be better, if one tones down the latter phrase’s sexual vibe—without removing it entirely. But whereas a deity’s act of seeing is normally only vicariously sensed by his or her seer, the invention of the motion picture camera and of the shot-reverse shot technique enabled the film viewer for the first time to assume, so to speak, both positions in the darshanic act. This is evident in surviving footage from pioneer filmmaker D.G. Phalke’s Kaliya mardan (‘the slaying of serpent Kaliya,’ 1919), in which a poster-like frontal tableau of the child Krishna (played by Phalke’s daughter Mandakini) dancing on the hood of a subdued giant cobra yields to a Krishna-eye-view of the assembled crowd of worshipers, gazing at ‘him’ in reverent awe. This technique became a commonplace in mythological films (for a sustained example, see the first song sequence in Jai Santoshi Maa, 1975), but its ubiquity should not obscure its religious significance. The camera’s invitation to gaze through the deity’s (or star’s) eyes heightens the experience of the reciprocity of darshan, closing an experiential loop to evoke (in a characteristically Hindu move) an underlying unity[xxxvi].

Long overlooked even by scholars of Hindu religious traditions, the everyday concept of darshan (for which the key text remains Eck’s 1981 study) later came to be invoked in scholarship on Indian cinema[xxxvii]. Prasad’s extended discussion deserves comment. Noting the absence of studies of ‘the politics of darshan,’ he offers one in the context of his analysis of mainstream Hindi films of the 1950s and ’60s. He characterises these generically as variants on a ‘feudal family romance,’ which he defines as ‘typically a tale of love and adventure, in which a high-born figure, usually a prince, underwent trials that tested his courage and at the end of which he would return to inherit the father’s position and to marry’[xxxviii]. Prasad views this as a regressive narrative form, which, among other things, precludes ‘affirmation of new sexual and social relations based on individualism’[xxxix]. In his assessment, darshan itself is another vestige of ‘feudal’ values: ‘a hierarchical despotic public spectacle in which the political subjects witness and legitimize the splendor of the ruling class’[xl]. Extending this interpretation to Hindu worship, Prasad emphasises the necessity of a mediating Brahman priest who controls the experience for the worshiper and reinforces the latter’s abject position (e.g., ‘the devotee’s muteness is a requirement of the entire process’); identification with the object of ‘the darshanic gaze’ is impossible, he claims, except on a ‘symbolic’ level[xli].[xlii]

Prasad’s remarks suggest the triumph of ideology over observation; they contradict the diurnal realities of Hindu practice and the experiences described by worshippers themselves. Darshan emphatically does not require priestly mediation, and although prosperous temples usually employ Brahmans who tend to the needs of deities and prepare them for public viewing, one may easily observe how marginal such men are to the act of darshan; by and large, worshipers treat them as petty servant-bureaucrats.[xliii] Further, Hindu devotees are seldom ‘mute’ during darshan; they pray, sing, petition, wave oil lamps, and express highly individual behavior; uniform mass worship, such as prevails in a Christian service (or in choreographed temple scenes in Indian films) is strikingly absent in real shrines. Worshippers also make their needs (for flowers, sweets, and other tangible expressions of prasad or ‘grace’) known to priests.[xliv] These responses also occur at the numerous holy sites—including countless unattended roadside shrines and the puja room or niche in households and even shops—in which there is never a priest present. Further, Prasad’s stress on merely ‘symbolic identification’ suggests his assumption that Western notions of absolute transcendence, of God as the ‘wholly other’ to the human, apply to Hindu deities. But anyone who takes the trouble to read a purana or a devotional chapbook, or to watch a ‘mythological’ film, ought to feel uneasy with this assumption. Hindu deities are emphatically ‘like us’ in many ways; they share human emotions, desires, and needs. This is so partly because they are encountered and intensively ‘seen’ through a reciprocal transaction that is potentially empowering to the human participant.

A sensitivity to the interactive nature of darshan might provide a different way of thinking about the visual experience of film. If cinematic ‘realism’ offers an essentially voyeuristic peep into, in Christian Metz’s words ‘a world that is seen without giving itself to be seen,’ the self-conscious style of the Indian popular film provides what Prasad rightly calls ‘a representation that gives itself to be seen’ (Prasad, citing Metz 1986; ibid. 72-73). This indeed parallels what Hindu deities do on the stages of their shrine-theatres, but their viewers’ response is neither stupefied nor mute. Unlike the ‘gaze’ of Western film theory, darshan is a two-way street; a visual interaction between players who, though not equal, are certainly both in the same theatre of activity and capable of influencing each other, especially in the vital realm of emotion.

Hearing

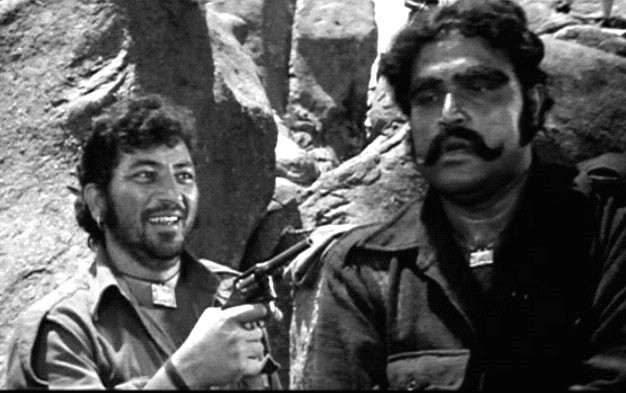

Fig. 3: ‘Kya dialogue hai!’ Amjad Khan (left), as the sadistic villain Gabbar Singh in Ramesh Sippy’s superhit Sholay (‘flames,’ 1975), gave speeches that were widely reproduced in chapbooks and on audiocassette.

Discussions of the conventions of Indian popular cinema in terms of those of pre-modern performance genres often invoke ancient Sanskrit drama and its authoritative treatise, the Natya Shastra, yet they seldom offer detailed information about this text. This is unfortunate, since the Natya Shastra is indeed a key moment in the Indian tradition of thinking about performance, and its relevance for film theory potentially goes beyond the stylistic similarities that link the theatre it describes with the latest Hindi or Tamil melodrama.[xlv] A treatise in thirty-six chapters, the Natya Shastra purports to describe the origin and development of drama as well as to treat comprehensively of virtually every aspect of the composition and staging of plays.[xlvi] Although the text at one point concedes the possibility of a theatrical style based on naturalistic imitation of human behaviour (which it terms lokadharmi or ‘according to the way of the world’—i.e., ‘realistic’), it disposes of this in a mere two verses[xlvii], and instead devotes itself to what it terms the ‘theatrical’ or ‘artificial’ style (natyadharmi), though natya (literally, ‘to be danced’) should not be translated generically as ‘theatre.’ Rather, it refers to an operatic dance-drama characterised by an alternation between spoken and sung passages, and in which ‘speech is artificial and exaggerated, actions unusually emotional, gestures graceful…’[xlviii].

The Natya Shastra devotes chapters to the design of stages and to props, costumes, and makeup, but the bulk of the text is preoccupied with the expression of emotion through the body via speech, music, and gesture. Its obsessively tidy classifications (about which I shall say more) include descriptions of thirty-six different ‘looks’ (to which it gives primacy in emotional expression[xlix]), twenty-four facial expressions, an equal number of hand gestures, and thirty-two foot movements used in dance and mime[l]. Two lengthy chapters are devoted to poetic meters, ornaments, and techniques, and two more, on theatrical speech, prescribe the use of several languages and dialects in accordance with the social status or geographical origin of characters (suggesting this drama’s aim to encompass a stratified and multilingual society, and making the label ‘Sanskrit drama’ an oversimplification). Six chapters, including three of the longest in the text, are devoted to musical performance, and the single longest deals with songs, which are to be interspersed throughout a play and performed by an ensemble located at one side of the stage. The fact that drama itself is sometimes defined synaesthetically as ‘visible poetry’ (drishya kavya)[li] suggests the aptness of the standard Indian-English word for the visuals in a modern film song sequence, which are identified as the ‘picturisation’ of the music and lyrics.

This format of alternately spoken and sung performance, which gave great emphasis to poetic and musical expression of emotion, survived the demise of Sanskrit drama toward the end of the first millennium CE and became characteristic of a range of regional folk dramatic forms using vernacular languages; it was transferred to the urban proscenium stage by the (mainly Hindi/Urdu language) ‘Parsi theatre’ troupes of the 19th century[lii]. It also became, after the introduction of film sound to India in 1931, the standard format for commercial cinema. Just as, in Sanskrit and most regional languages, there was no word for ‘play’ that did not imply ‘music-and-dance drama,’ so Indian-English ‘film’ normally means one incorporating songs and dances, and there has never been a separate genre category of ‘musical’ in the Hollywood sense. The specialised skills of lyricists and composers are highly valued within the industry and among its fans, and their names are likely to appear on posters and billboards as a way of promoting a film (stars’ names seldom appear, since their faces instantly identify them). Since the 1970s, dialogue writers such as Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar have sometimes received equally high billing, and the scripts of many popular films have been published in booklet or audiocassette form.

The rhetorical and musical dimensions of Indian popular cinema, like those of older genres of performance, present a challenge to English-language viewers. Although the hybrid melodies, instrumentation, and rhythms of film songs may be appreciated as music, the poetry of their lyrics is lost—even when (as is unfortunately not always the case) song sequences are subtitled on commercial DVD releases. Dialogue subtitles too mostly fail to convey the clever colloquial patois, dramatic innuendo, wordplay, double entendre, and inter-textual referencing that abounds in these films and that makes ‘filmi dialogue’ an everyday performance genre unto itself—an artificial but admired speech register that is jokingly referred to in such Hindi expressions as ‘filmi dialogue marna’ (‘to lay on film dialogue,’ i.e., speak in an exaggeratedly emotional manner). To a far greater extent than is the case in America, the remembered language of popular films—phrases from dialogue and lyrics of songs—circulate in everyday speech together with other bodies of oral tradition (such as aphoristic couplets from medieval poet-saints like Kabir and Mirabai) and contribute to a range of casual ‘performances’—as when one speaker cites part of a line of film dialogue and another completes it. In the party game antakshari (‘game of the last syllable’), players or teams compete to demonstrate their memory of song lyrics, with the last syllable of a remembered song-line yielding the first syllable of one to be recalled by the next contestant.[liii] Such practices reflect not simply the extent (distressing to some cultural critics) to which film language pervades modern Indian life; they also point to the continuing high valuation of oral rhetorical performance in general—including secular speeches, religious sermons (themselves often accompanied by music), and poetic recitations that sometimes attract stadium-filling crowds.

It is ironic to have to remind a Western critical audience—which is slowly becoming comfortable with the privileging of image over text and which lives in a culture in which poetry is in retreat, political discourse reduced to sound-bites, the art of rhetoric suspect, and the manipulation of emotion and desire increasingly achieved through visual content alone—of the artistic weight that, in successful Indian films, has long been carried by dialogues structured as rhetorical set-pieces and by songs that may have been penned by renowned poets. Given their importance to audiences, the rhetorical and musical aspects of popular films have been grossly neglected in scholarly analysis—dismissed as insignificant relics of earlier performance genres[liv], or as mere ‘spectacle’ randomly inserted into the cinematic narrative[lv]. Other scholars, however, have proposed that the ‘message’ of an Indian film is hardly confined to its plotline (especially given the characteristically ‘loose’ form of the latter, to be discussed shortly), and that the work of song, dance, and dialogue is at times precisely to fissure the surface ideology of a film, by allowing the expression of suppressed desires and subjectivities[lvi].

Incidentally, the intellectual critique of ‘song and dance’ in Indian dramatic performance is not new. For all its discussion of songs, the Natya Shastra cautions against excessive use of them[lvii], and at one point the sages, to whom the treatise is being narrated by the legendary author Bharata, ask him why it is necessary, after all, to have dance in a natya, adding ‘How can dance convey a message?’ Bharata responds by observing that, although dance has no ‘meaning,’ it is invariably used in drama because ‘it creates beauty.’ He then adds pragmatically (and this seems to clinch the matter), ‘Generally, people like dance. It is also considered to be auspicious…. It is also a diversion’[lviii].

Tasting

Fig. 4: The lovers (Shahrukh Khan and Kajol) in Aditya Chopra’s massively successful Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (‘The True Lover Will Take the Bride,’ 1995) break a one-day fast by feeding each another.

One of the most influential and intriguing components of the Natya Shastra is its aesthetic theory, elucidated mainly in chapters six and seven. These serve as locus classicus for the concepts of bhava (‘emotion, mood’) and rasa (‘juice, flavour, essence’) which were further developed by later writers on drama and poetry, and indeed by theologians and metaphysicians—for aesthetic pleasure came to be regarded as on a continuum with or as a means to transcendental bliss (ananda). The seeds of this understanding are already present in the Natya Shastra’s own frame story (to be discussed below) which identifies theatre as a ‘fifth veda’ synthesising and in a sense superceding the traditional four bodies of revealed knowledge.

Like the Greek philosophers, ancient Indian thinkers were interested in why people enjoy theatre and in what they ‘get’ from it; specifically, in why they derive pleasure from seeing things on stage that would not be pleasurable if encountered in ‘real’ life. Whereas Aristotle posited katharsis, a purgation or cleansing, the author or authors of the Natya Shastra and their successors favoured a more complex explanation. In their view, primary and individualised human emotions (bhava) generated by the multifarious experiences of life are transmuted, through their representation by actors in a dramatic spectacle, into universalised emotional ‘flavors’ (rasa) that may be savored by audience members at the safe remove that theatre provides[lix]. The complexity of the theory arises in part from the elucidation of the primary emotions, which comprise love, mirth, anger, pity, heroic vigor, wonder, disgust, and terror—these eight become sixteen, since each bhava induces a corresponding rasa, which then proliferate geometrically into further sub-categories[lx]. What is most notable for my purpose is the assumption that, although a given performance will have a predominant rasa (thus a farce will be dominated by hasya rasa or the comic flavour, and a martial saga by virya rasa or the heroic), it is expected to offer a range of others as well. The imagery used is somatic and in fact gustatory, locating aesthetic pleasure in the body as much as in the mind; thus the text asserts that a drama’s rasa may be likened to the taste produced ‘when various condiments and sauces and herbs and other materials are mixed…’[lxi]. Further, it is understood that rasas are fleeting and may be enjoyed serially; a successful performance is thus akin to a well-designed banquet or smorgasbord, serving up rasa after rasa for spectators to savour.[lxii]

Although modern filmgoers seldom specialise in classical aesthetic theory, the vocabulary of bhava and rasa remains in use in Indian vernaculars, and the broad cultural consensus is that a satisfying cinematic entertainment ought to generate a succession of sharply-delineated emotional moods. Whereas Western viewers are sometimes distressed by what seem to them a mélange of genres (comedy, action-adventure, romance, etc.) and too-abrupt transitions in mood (a tragic scene yielding to a comic one, and then to a romantic song set in a fantasied landscape), Indian audiences take such shifts in stride and may even complain if a film does not deliver the anticipated range of emotions (though they also at times complain of pointlessness in film sequences if the moods evoked do not in some sense cohere into a satisfying whole).[lxiii] Performance theorist Richard Schechner has observed that whereas Western theatre tends to be ‘plot-driven,’ Indian theatre is more typically ‘rasa-driven,’ and has suggested that a familiarity with (what he terms) ‘rasaesthetics’—a more somatically-based understanding of the effect of performed emotions on the spectator—could enlarge the conceptual vocabulary of Western critical theory.[lxiv]

A final aspect of the Natya Shastra deserves mention: its frame narrative, which situates the origin of drama within the classical Hindu time-cycle of four ages (yugas) that become successively debased and enervated. In the first chapter of the treatise, the gods complain to Brahma that in the current kali yuga (the fourth and darkest age), people no longer understand the vedas, moreover, men of the lowest class (Shudras) and women are forbidden even to hear them. Hence there is a need for ‘something which would not only teach us but be pleasing both to eyes and ears’[lxv]. Brahma obliges by distilling the essence of the four vedas into a fifth, which he terms the natya veda (‘performed knowledge’), and which is to be accessible to all ranks of society. He then teaches it to the sage Bharata who in turn transmits it to his hundred sons; assisted by heavenly courtesans (apsaras), they perform the first play on a celestial stage[lxvi]. This narrative, interrupted by thirty-four chapters on theatrical technique and poetic theory, resumes in the final chapter of the work when the sages ask Bharata how drama was brought down from heaven to earth. He replies that, in time, his actor-sons became arrogant and began performing only satires, in which they ‘encouraged rustic manners’ and even lampooned sages. The latter became angry and cursed the actors to be born on earth in a debased condition: ‘You will become mere Shudras…and those to be born in your line will be impure. And your posterity will be dancers who will worship others, along with their wives and children….’[lxvii]. When his disgraced sons threaten suicide, Bharata comforts them by reminding them that their art, after all, comes from the creator himself; he sends them to earth to fulfill the curse but also offers a remedy for it—they will obtain royal patrons and acquire prestige, and hence ‘will no longer be despised by Brahmanas and kings….’[lxviii]. The final verses of the text, which identify the ‘fruit’ or merit that accrues to one who reads it, declare that those who study the Natya Shastra, produce plays in accordance with its precepts, or watch such plays as audience members will all ‘derive the same merit as may be derived by those who study the vedas, those who perform sacrifices….’[lxix].

The term shastra is usually rendered ‘treatise’ or ‘textbook,’ and refers to a class of Sanskrit works purporting to offer systematic exposition of a given subject; there are shastras on architecture, grammar, law, politics, erotics—even, allegedly, one for thieves. Typically, a shastra opens with a myth revealing a divine source for the given body of knowledge and ultimately relating it to the veda—the transcendent revelation preserved chiefly by Brahmans. Typically too, the organization of material in a shastra reveals an almost obsessive concern for classification, usually according to numerologically significant schema (e.g., the sixty-four coital positions famously cataloged in the Kamasutra, a shastra devoted to eros); in these respects the Natya Shastra is quite standard. But what was the intended use, and who was the intended reader, of such a text? Some scholars have proposed that, although the shastras claim to treat of the invention of disciplines and to offer instruction in them, they may be better understood as descriptive and ideological works that seek to bring existing bodies of knowledge and practice within the domain of the totalising Brahmanical project[lxx]. Like the 18th century French encyclopaedists or the British ‘gazetteer’ writers of colonial India, the authors of the shastras were as much concerned with demonstrating their own intellectual hegemony as in accurately describing the world around them.

Read from this perspective, the Natya Shastra’s frame story suggests the pre-existence of a flourishing and popular theatre, performed by mainly low-class actors but appealing to diverse audiences. The authors of the shastra were both pleased and concerned with this phenomenon; they sought to explain it by affirming the genealogical credentials of natya—its basis in the transcendent source of (Brahman-brokered) knowledge—but also to explain its present, debased condition (which included vulgar stage business and the satirizing of high-born people like themselves), and to propose means for its purification and improvement. The rules that pad nearly every chapter seem aimed at the latter goal; they mirror the detail of older scriptures that minutely prescribed procedures for Vedic fire sacrifices—the ultimate model of ritually correct performance—and they also reflect the authors’ preoccupation with social hierarchy[lxxi]. These rules and schema may have been extrapolated from a handful of admired plays and then gratuitously universalized[lxxii], but although their enumeration may have provided satisfaction to some elite connoisseurs, it seems unlikely that ancient authors and performers were constrained by such strictures. Most pre-modern theatrical training relied on apprenticeship and oral tradition rather than on textual study, as remains the case, for example, in Indian music despite the existence of numerous shastras devoted to the classification of ragas or melodies, talas or rhythmic cycles, and musical techniques. But there is evidence that some later Sanskrit playwrights did try to adhere to the ‘rules’ attributed to Bharata; not surprisingly, this mostly resulted in unsatisfying plays. Paradoxically, the growing prestige of the Natya Shastra may have contributed to the decline of the very drama it celebrated[lxxiii].

My historically contextual reading of the Natya Shastra suggests the ideological agenda behind its recipe for theatre: at a time when Vedic sacrifice was in decline and Brahman authority threatened, the authors of the shastra sought to explain and reform a popular art form that ‘appealed to everyone’ by likening it to ritual performance and by enveloping it in daunting Sanskrit terminology. The grand theories of our own yuga sometimes seem to me to have a similar aim—the product of increasingly marginalised humanist academics who perceive the greater prestige of ‘hard’ science on the one hand and of mass-market entertainment on the other, and who advance haughty analyses of the latter that imitate the former’s technical jargon. Academic criticism of Indian popular cinema displays a particular penchant for reductive typologies and stern agendas of improvement, based on a standard that no actual filmmaker ever seems to achieve—only the scholar-critic possesses the knowledge to imagine the ideologically perfect film.[lxxiv]

Telling

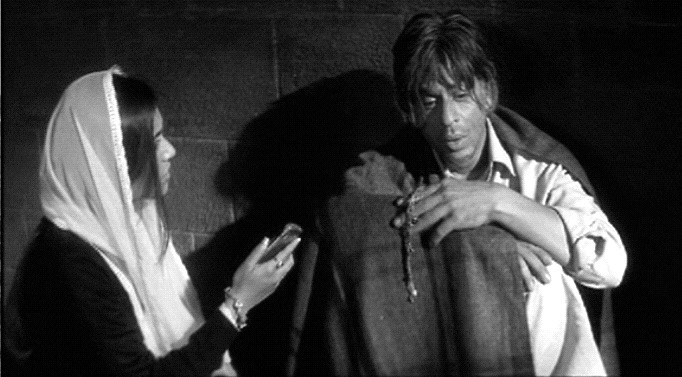

Fig. 5: A mysterious prisoner in a Pakistani jail (Shahrukh Khan) begins telling his life story to a human rights lawyer (Rani Mukherjee) in the frame-narrative of Yash Chopra’s Veer-Zaara (2004).

There is general consensus among scholars that the storytelling conventions of Indian popular cinema are significantly different than those of most other film industries. Accounts of that difference generally focus on the ‘complexity’ and ‘loose structure’ of the plots, their lack of a ‘linear’ narrative, and the presence of ‘discontinuities’ in the form of both subplots and song and dance sequences. Such understandings take the form of assessments either negative or positive. Bengali director Satyajit Ray complained, back in 1976, of the commercial cinema’s ‘penchant for convolutions of plot and counter-plot rather than the strong, simple unidirectional narrative,’ such as he favored in his own films[lxxv]. Dissanayake and Sahai, on the other hand, offer a more appreciative and culture-specific assessment: ‘Although…Indian cinema was heavily influenced by Hollywood, the art of narration with its endless digressions, circularities, and plots within plots remained distinctly Indian’[lxxvi]. Rosie Thomas writes of ‘the baroque surface of the Hindi film’[lxxvii], and describes it as a form ‘in which narrative is comparatively loose and fragmented, realism irrelevant, psychological characterization disregarded, elaborate dialogues prized, music essential, and both the emotional involvement of the audience and the pleasure of sheer spectacle privileged throughout….’[lxxviii]. Her further statement that such an entertainment, to be successful, ‘involves the skillful blending of various modes…into an integrated whole that moves its audience’[lxxix] would of course be disputed by some. Prasad, too, notes the commercial cinema’s preference for ‘the all-inclusive film, whose vision of the world tends to be multi-faceted, episodic, and loosely structured,’ but he sees this as resulting in ‘a textual heteronomy whose primary symptom is the absence of an integral narrative structure’[lxxx].

Most scholars explain the structure of popular films historically, citing the influence of older storytelling genres, particularly those of the great cultural epics—an argument I will be examining more closely in this section. Prasad is the major dissenter, however, and his counter-theory needs to be considered. Although he alludes to the conventions of the ‘romance’ in pre-modern literature and also points to the resemblance of Hindi films to early American melodramas, his primary explanation of cinematic narrative structure is grounded in the economic and labour practices of the Indian film industry[lxxxi]. Dismissing the ‘overemphasis on cultural difference abstracted from the social formation as a whole’ that he finds characteristic of the cultural-historical approach[lxxxii], Prasad seeks to ground the conventions of Bombay cinema in ‘anarchic backward capitalism’[lxxxiii] and in its adoption of a ‘heterogeneous form of manufacture,’ in which films (like the watches in Marx’s classic example of this mode of production) are assembled from separate components produced by specialist craftspeople[lxxxiv]. The screenplay, itself sometimes authored in committee, is only one of these components; music and song lyrics are others, as is star persona (an element predefined by other films); dialogs are composed by another specialist or set of specialists, and action sequences choreographed by another. Prasad concludes that ‘the story here occupies a place on par with that of the rest of the components, rather than the pre-eminent position it enjoys in the Hollywood mode’[lxxxv].

Although the specialisations Prasad notes are indeed standard in the Hindi film industry, his implied contrast with a supposedly more ‘coherent’ Hollywood product appears overstated. Given the fact that films are complex manufactured products that require large teams to create, Prasad fails to convince me that film production in India is inherently more ‘heterogeneous’ than elsewhere. Moreover, his invocation of market ‘anarchy’ (in which multiple independent producers operate under unstable financial conditions) does not explain why legions of producers, directors, and studios independently make similar choices in assembling films. Indian filmmakers are well aware of the alternative ‘tighter’ narrative models of foreign cinemas, yet they consistently reject these, even as they readily appropriate specific plot elements and shot sequences. The fact that screenplay and dialogue are often authored by different persons is of course significant (though such a division of labour is not unheard of in the West). This practice reflects a generally looser cultural notion of ‘authorship’ as well as the (already noted) high valuation of rhetorical art. Yet the inclusion of such specialised efforts does not preclude the achievement of a harmonious whole, and such ‘coherence’ within the desired mix of ingredients in a commercial film is often praised by Indian viewers. In my view, the theory of ‘heterogeneous manufacture’ fails to fully account for the enduring preference of Indian filmmakers and their audiences for epic-length, episodic, and ‘baroque’ narratives. The study of cultural and literary history yields more compelling explanations, and it is to these that I now turn.

The influence of the classical epic traditions must certainly be noted. References to the Ramayana and Mahabharata—each of which should be understood not as a fixed, Sanskrit-language text but rather as a multiform and intertextual storytelling tradition existing in hundreds of literary versions as well as in oral and visual performances—abound in popular art, from ubiquitous ‘god posters’ to comic books to television advertising. Their themes (which include the tension between social duty and personal satisfaction and between the lifestyles of renunciant and householder, the nature and transmission of authority, and the proper relationships between genders, family members, and social classes) are alluded to in everyday speech and formal discourse; images of their principal divine characters inhabit countless temples and shrines. Yet the assumption that these epics ‘influence’ popular films must be qualified. Though there have been scores of film versions of each epic or (more commonly, given their length and complexity) of subsidiary episodes drawn from them, the sum total of such productions still comprises only a small portion of cinematic output. Far more common are allusions, in ‘secular’ stories, to epic motifs via character names, dialogue, or visual coding. As Booth observes, epic content ‘usually forms a secondary or allusory subtext rather than primary text’ in Hindi films[lxxxvi]. Such allusions presume an audience that is broadly familiar with the epics and offer it a pleasurable experience of recognition, but they coexist with many other references—to folktales, historical and current events, and indeed other films. It is the structure of the epics (and, as I will argue, of a much larger body of popular narrative) rather than their specific content that presents a parallel to the way in which film stories unfold. As Dissanayake and Sahai observe, ‘Instead of the linear and direct narratives that conceal their narrativities that we encounter in Hollywood films, the mainline Indian cinema presents us with a different order of diegesis that can best be comprehended in terms of the narrative discontinuities found in the Ramayana and the Mahabharata’[lxxxvii]. What is the nature of these ‘discontinuities’?

Apart from their sheer prolixity, with stories that span generations (three in the Ramayana, seven in the Mahabharata) and introduce scores of important characters, the pan-Indian epics share a number of structural features. They are both ‘emboxed’ by frame narratives that identify their authors (who are themselves characters in their stories) and the circumstances of their telling, and that thus recapitulate the conventions of oral performance. Yet once the ‘main’ tale begins, unfolding as a flashback, it too may be regularly interrupted by subordinate tales, which branch off from and return to it and which it, in turn, ‘frames.’ These sub-stories often recapitulate themes found in the larger plot, but with variations—as in a baroque fugue, or (more aptly) a classical raga. Though they may strike Western readers as ‘digressions’ from the ‘main story,’ they are not regarded as such by their primary audience, which savours the slow unfolding of the tale through such detours. In oral storytelling and dramatic performance, these subsidiary stories often provide the occasion for humourous set pieces, poems or songs that take on an independent life, interludes set in alluring or magical realms, or flashbacks, dreams, prophecies and other devices that suggest the designs of fate or the illusory and cyclical nature of time. The effect is indeed non-linear; rather it is one of circles within circles, or of gears set within larger gears—as in a clockwork—that periodically ‘click’ back together to slowly advance the largest, encompassing story-wheel toward its already-anticipated but repeatedly-deferred conclusion. Aesthetically, the effect may be compared to the intricate melodic and rhythmic patterns of Indian music, that bifurcate into lengthy thematic improvisations but regularly return to a common beat known as the sama—a moment that produces sighs of delight from knowledgeable listeners.

This structure can be illustrated with reference to the Ramayana, the shorter and more ‘linear’ of the two epics (though the unwieldy Mahabharata is even more interesting, structurally speaking). The story begins at its end, with sage Valmiki (after a further frame story in which he invents the first poetic meter) composing the story of Rama and teaching it to twin boys among his disciples; the boys then go to sing it in the court of its own hero, now a middle-aged king engaged in a multi-day Vedic ritual. Unbeknownst toRama (but known to the audience), the boy bards are his sons whom he has never seen, due to his having exiled his pregnant wife—a tragic event that will not be recounted until nearly the end of the tale. The story then unfolds, backtracking to the circumstances surrounding Rama’s birth. Within this story many others are told, especially during Rama’s youthful training by a sage; most of these tales reflect on the tension between the opposing lifestyles of ascetic sages and householder kings—prefiguring a resolution of this tension through Rama’s own destiny as ideal dharma-ruler. In its final episodes the story returns to its frame for a dramatic scene in which Rama recognises his lost sons and is (unsuccessfully) reunited with his banished wife.

Both the Ramayana and its longer, darker, and more Realpolitik-savvy cousin-brother, the Mahabharata (in which an extended royal family is riven by internal squabbles, leading to a fratricidal and apocalyptic war that virtually destroys the ruling class) are essentially about families and resonate with the real experience of many Indians who (regardless of their actual living arrangements) conceptualise themselves as members of close-knit extended kin groups. Both epics suggest that their familial microcosm (idealistically united in the Ramayana, fatally split in the Mahabharata) may also stand for society, or in modern times, for the nation. They are inherently ‘political’ as well as ‘religious’ stories, and their easy slide from interpersonal drama to social allegory is a trait shared with many mainstream films. So is their treatment of personality, which tends to divide contrasting psychological traits among a group of related characters, rather than locating them in a single conflicted individual. Thus the Mahabharata’s five Pandava brothers, who share a common wife, often seem to function as one composite hero split into different selves. The popular cinema also tends to externalise psychological conflict and distribute it over several characters—e.g., Ashis Nandy has noted the extraordinary popularity of the cinematic motif of the double, in which a single actor portrays twins, coincidental look-alikes, or a successively reincarnated person[lxxxviii].

Yet the Ramayana and Mahabharata have always shared the spotlight and interacted, not merely with each other, but with other genres of popular storytelling that adhere to some of the same narrative conventions—favouring sprawling, epic tales—but that foreground rather different values. Regional folk epics, such as that of Pabhuji in Rajasthani[lxxxix], Dhola in Hindi[xc], Palnadu in Telugu[xci], and the ‘three twins’ in Tamil[xcii], often celebrate the ethos of lower-status but upwardly mobile groups, linking them to pan-Indian and Sanskritic mythology but also asserting local identity and agency. Like many modern films, these complex tales may themselves make oblique reference to the pan-Indian epics, as when the popular Hindi martial cycle of Alha-Udal is interpreted as a ‘Mahabharata of the kali yuga,’ in which the vanquished ‘enemy’ cousins of the older epic, now reincarnated, become victors[xciii]. Structural analysis of such epic storytelling—traditionally performed by bards in multi-session, all-night performances—has yielded some interesting typologies, such as Stuart Blackburn and Joyce Flueckiger’s division of Indian folk epics into the broad categories of martial, sacrificial, romantic, and mythic[xciv]. Gregory Booth has proposed that these categories might better serve for analysing mainstream films than the vague and overlapping commercial ‘genre’ divisions sometimes invoked (e.g., ‘mythological,’ ‘social,’ ‘historical’;[xcv]).

The prestige of the Sanskrit epics has also tended to eclipse, at least for outsiders, the popularity of narrative traditions that, although similarly imbued with myth and fantasy, express a decidedly more worldly, sensual, and entertainment-oriented ethos. Such are the popular tales of the first millennium CE that eventually found their way into the massive Sanskrit anthology Kathasaritsagara (meaning: Ocean of rivers of the great story), where they are framed as a heavenly entertainment told by Shiva to his wife Parvati. These tales often feature heroes who are wily merchants, disenfranchised princes, or poor (but not especially pious) Brahmans, and whose aim is less the pursuit of dharma than the acquisition of wealth and worldly power; they also enjoy love affairs with glamorous women along the way. To accomplish their ends, the heroes often undertake impersonations, commit thefts, and carry out adulterous seductions, and though they are occasionally assisted by supernatural forces, they just as frequently skewer both pious pomposity and folk superstition. The pace and style as well as the self-assertive ethos of these ‘action-adventure’ tales, which are characterised by abrupt plot turns and mood shifts, dramatic reunions and recognitions, and lyrical interludes set in demi-divine or magical realms, are indeed suggestive of masala films[xcvi]. They also include a feature that is generally not foregrounded in the ancient epics (though it sometimes enters into their oral retelling)—a strong current of (often irreverent) humour. Though recorded in a number of famous texts, such stories remained in oral circulation throughout the pre-modern period, and with the coming of typography found their way into the flourishing Hindi-Urdu chapbook literature known as qissa and kahani[xcvii].

There remains another confluent current of Indian popular narrative to be noted, one that is of special significance for popular cinema. I refer to a strongly Islamicate strain, which has generally been overlooked by scholars invoking the ‘epic’ genealogy of mainstream films. I use ‘Islamicate’ rather than ‘Islamic’ to refer not to the impact of Muslim religion, but to the influence of a cosmopolitan urbanised culture that set norms for much of western, central, and south Asia for roughly a thousand years. This culture, reflected in (for example) styles of dress, diction, architecture, and music, was embraced to a considerable extent even by polities that remained ‘Hindu’ in their ritual practices or that even articulated an ‘anti-Islamic’ ideology[xcviii]. The narrative traditions of the medieval Perso-Arabic and Turkic-speaking world had themselves been influenced by ancient Indian story literature (for South Asia, or al-Hind, was famed to the west as the ‘land of story’), but they had also evolved their own distinctive tales, in which fairies and jinns took the place of the demi-divine beings of Indian lore, sorcerers replaced tantric adepts, and the hero’s love affairs were inflected with a Sufi flavor, permitting them to be read as allegories of a divine quest. Though the pain of separated lovers had long been celebrated in Indian poetry and story, the Sufi influence, together with the strict gender codes of many Islamic societies, accentuated the theme of a hero’s consuming infatuation for an inaccessible beloved, culminating in romantic desperation and even death (‘martyrdom’ in the way of love, mystically allegorised to fana or the ‘annihilation’ of self in divine unity). Entering India with Islamic traders, warriors, and wandering Sufi fakirs, the Islamicate narrative traditions, especially those of the Persian mathnawi and dastan, combined with indigenous strains to produce hybrid manifestations of extraordinary vigour, ranging from local folk sagas (such as the Punjabi tale of the doomed lovers Hir and Ranjha[xcix]) to courtly romances that found their way into multi-volume literary form. Two genres of the latter deserve special mention here.

In the aftermath of the conquest of much of northern and central India by Muslim rulers at the close of the 12th century, Sufi orders greatly expanded their activities, establishing khanqahs or ‘hospices’ (usually built around the tomb of a revered Sufi preceptor) that attracted a diverse clientele by no means restricted to Muslims. Sufis were particularly interested in indigenous mystical traditions, and a lively interaction—at times adversarial, at times dialogic—developed between fakirs and yogis. The older form of the mathnawi had been developed primarily in Persian cultural areas as an elaborate love story, generally involving a heroic quest, which could be enjoyed as poetic narrative but also savoured as mystical allegory. As early as 1301 AD, an Indo-Persian author, Hasan Dihlawi, crafted one such work, Ishq-nama (meaning: the book of love) by drawing on a Rajasthani legend of passionate and doomed lovers[c]. Beginning later in the 14th century, a group of Sufi authors in northeastern India used similar conventions to craft epic-length romances in the local lingua franca that they called Hindavi (‘the language of Hind’). They fused the intense romanticism and quest themes of Persian literature with characters, legends, and a general cultural ambience that was entirely Indic and indeed Hindu—thus after a prologue that invoked Allah and Muhammad, the works slipped into the pattern of Indian tales involving princes who became yogis, and featuring miraculous interventions by gods such as Shiva and Parvati. Four such premakhyans or epic-length ‘love stories’ survive, the last composed in 1545, but there is evidence of others that have been lost[ci]. Although there has been much speculation regarding the intended audience and use of these works, there is evidence that they were recited in both royal courts and Sufi hospices[cii]. Significantly, one of the rare accounts of an informal performance from the Mughal period, written in about 1640 by a Jain merchant from Banaras, describes his ‘singing’ of two of the Sufi romances composed about a century earlier during regular evening sessions with a group of friends[ciii]. From today’s perspective, what is also striking about these romances is their anticipation of certain conventions of popular cinema—complex plots involving a love-triangle of a hero and two heroines, lyrical set-pieces placed in exotic or fairytale landscapes, and a pattern of the repeatedly-deferred union of the principal lovers in order to develop the rasa of passionate love-in-separation.

Oral storytelling remained a popular entertainment form in Islamicate South Asia and was continually reinvigorated by Persian-language traditions. During the Mughal period (ca. 1555-1765), there was a virtual craze among both aristocrats and commoners for Persian sagas called dastans, which were long, episodic romances narrated by professional bards. The genre was gradually Indianised, with significant transformations, not the least of which was that it shifted into Urdu, the non-elite lingua franca of the Mughal Empire. The traditional subject matter of the Persian dastan was razm o bazm—’war and romance’—but characteristically, the Indian dastango (storyteller) added two more masalas to the blend—magic (tilism) and trickery (‘ayyari). The former allowed for fantastic otherworlds and enveloping ‘enchantments’ in which a hero might wander for years; the latter highlighted the talents of a comic but dextrous sidekick—a trickster-like figure who added a leaven of bawdy or scatological humour and worldly-wise pragmatism to the hero’s lofty ideals, and who thus resembled the clown-like vidushaka of Sanskrit drama. Significantly, although many of the themes of the dastan are shared with the aristocratic romances found throughout Europe and the Middle East, humour is generally downplayed elsewhere; in India, a ‘comedy track’ often takes the spotlight[civ].

The most popular Indian dastan was that of Amir Hamzah, an uncle of the Prophet and a minor figure in the early history of Islam. Like Alexander the Great before him, Hamzah captured the imagination of storytellers and became the central figure in a vast cycle of tales, full of expressions of Islamic piety yet essentially secular and escapist in theme. His adventures were recited on the steps of the Jama Masjid or ‘great mosque’ in Delhi, and some aristocratic connoisseurs kept their own in-house dastan-gos to endlessly narrate the cycle. Like the heroes of the Sufi premakhyans, Hamzah acquired, in the course of his exploits, two principal wives, one human and one a fairy—though he enjoyed a host of other amours. His first and most passionate love, for the Persian princess Mihr Nigar, was unconsummated for eighteen years while he wandered in the fabulous realm of Qaf, home of fairies and jinns. Storytellers alternated between the trials of Hamzah and those of his suffering beloved, who was repeatedly rescued from violation by the ingenuity of Hamzah’s ‘ayyar sidekick, ‘Amar. Ultimately Hamzah was united with Mihr Nigar—his fairy wife joined the household, and he lived happily until his eventual (historical) martyrdom in one of the Prophet’s battles. Within this framework, which spans four generations, endless expansions and permutations were possible, and the length of a narration depended only on the ingenuity of the teller and the enthusiasm of listeners. Both were evidently considerable, and surviving accounts mention daily narrations that went on for months. Versions of the Hamzah cycle found their way into literary form during the Mughal period, entering the libraries of connoisseurs as illuminated manuscripts. But the real explosion of Hamzah texts occurred with the spread of printing during the second half of the 19th century. It culminated in the version published by Naval Kishore of Lucknow, a Hindu enthusiast for Islamicate literature (this was not unusual), who assigned a team of scribes to three oral dastan-tellers and, between 1883 and 1905, issued what is almost certainly the world’s longest narrative—a Mahabharata-dwarfing Dastan-e amir Hamzah comprising forty-six volumes averaging nine hundred pages each. This staggering work was not simply a pulp-fiction curiosity; it was a literary achievement, an ‘astonishing treasure house of romance, which at its best contains some of the finest narrative prose ever written in Urdu’[cv]—though it should be noted that its prose is regularly interspersed with lyrical interludes. It was also, by the standards of the time, a bestseller: ‘…the delight of its age; many of its volumes were reprinted again and again’[cvi]. According to Pritchett, this literary dastan reached ‘an extraordinary peak of popularity’ at the close of the 19th century, and then gradually lost readership, by the end of the 1920s, to the emerging genres of novels and short stories, though the early examples of these were themselves ‘very dastan-like’ (ibid.).

A reader of the Hamzah dastan today (made available in Pritchett’s condensed but artful translation) can note the similarities of its repetitive episodes, its themes of love, honour, and heroism, as well as its sheer scope and narrative profligacy, both to earlier Indian genres and to the ‘dastan-like’ narratives of popular cinema. The period that witnessed the apogee of Hamzah’s popularity coincided with both the floruit of the Parsi theatre (whose plays drew equally on Hindu epics and Indo-Islamic romances) and also the beginnings of the cinema. The Islamicate strain in the latter is often overlooked. Although the Maharashtrian Brahman D.G. Phalke based his early feature films on Hindu legend, the growing industry soon reached out to a broader narrative pool. With the coming of sound, Persianised Hindi-Urdu with its strong literary and romantic associations became the dominant language of Bombay cinema (Kesavan 1994), and plots were often drawn from Indo-Persian romances, as in the five remakes of the story of Laila and Majnun—a tale that ranks with that of Devdas as one of the most often filmed in Hindi cinema[cvii]. The highly-charged lyrics of Hindi filmsongs, with their Islamicate vocabulary, are not merely conventionalized inserts without ‘social currency’[cviii]; they evoke a world of romantic and refined entertainment that encodes powerful emotional ideals as well as a history of cultural syncretism.

Conclusion

Fig. 6. Director Guru Dutt as Director Suresh Sinha in the final scene of his tragic meditation on cinematic (and mundane) illusions, Kaagaz ke Phool (‘Paper Flowers’ 1959).

Among the conventional answers to the titular question (‘Is There an Indian Way of Thinking?’) that A.K. Ramanujan briefly entertained was the assertion that there once had been such a distinctive Indian ‘way,’ but that modernity and globalization had largely eliminated it[cix]. Similarly, some may propose that the cultural forms and practices discussed in this essay indeed influenced Indian films of past decades, but that they have become increasingly irrelevant in recent years. Certainly, market liberalization and the expansion of consumer culture since 1990, coupled with the impact of cable television and digital technologies such as CGI, have contributed to recent big-budget films having a significantly ‘slicker’ and more ‘world-class’ look, and such factors as the growing power of the middle classes and the rise of multiplex cinemas catering to ‘niche’ markets have also contributed to more experimentation by mainstream filmmakers (including a growing number of shorter films that contain no diegetic songs)—a healthy trend that seems likely to continue. Yet, to my view, many of the most popular Hindi films of recent years continue to exemplify the ideologies and practices I have described, and their characteristic intertextuality now delights an audience that, because of ‘classic movie’ cable channels as well as streaming websites, is even more keenly aware of Indian cinema’s distinctive genealogy and of its visual, aesthetic, and narratological conventions. And this brings me to Ramanujan’s—and my—conclusion.

After summarising some of the grand theories that account for (or deny) the uniqueness of Indian concepts and practices, Ramanujan attempted his own answer to his question. Citing his training as a linguist, he invoked the classification of grammatical rules as either ‘context-sensitive’ or ‘context-free,’ and extended these to the reigning self-idealisations of societies.

I think cultures (may be said to) have overall tendencies (for whatever complex reasons)—tendencies to idealise, and to think in terms of, either the context-free or the context-sensitive kind of rules. Actual behaviour may be more complex, though the rules they think with are a crucial factor in guiding the behaviour. In cultures like India’s, the context-sensitive kind of rule is the preferred formulation.[cx]

Whereas Euro-American society, according to Ramanujan, imagines itself to be founded on principles that are ‘universal’ and ‘rational’ (hence, context-free), indeed to conceptualise space and time—’the universal contexts, the Kantian imperatives’—as uniform and neutral, Indian epistemologies, for which ‘grammar is the central model for thinking’ favor typologies and hierarchies that particularize and frame within complex contexts[cxi]. Ramanujan cites numerous examples, ranging from legal statutes (in which penalties for crimes depend on the social identity of the parties involved) to erotic treatises (‘…the Kamasutra is literally a grammar of love—which declines and conjugates men and women as one would nouns and verbs in different genders, voices, moods, and aspects’) to classifications of time and space that eschew ‘uniform units’ in favour of contextualised specificities. In poetry, he cites the ‘taxonomy of landscapes, flora and fauna, and of emotions’ that establish contexts for poetic imagery, and in narrative literature he points to the ubiquitous practice of framing, invoking the epic traditions of ‘metastory’ that frame and encompass subsidiary narratives[cxii]. Ramanujan advises,

We need to attend to the context-sensitive designs that embed a seeming variety of modes (tale, discourse, poem, etc.) and materials. This manner of constructing the text is in consonance with other designs in the culture. Not unity (in the Aristotelian sense) but coherence, seems to be the end.[cxiii].

Yet the ability to perceive the coherence of ‘context-sensitive’ texts will of course depend on the context of the reader. Victorian critics, idealizing a ‘realist’ aesthetic and a tightly-constrained temporal and spatial canvas, typically found Indian narrative cycles to be disordered and incoherent, even (they said) the products of a childish and febrile imagination. It took the sea-changes of the 20th century—the crisis of the World Wars and of imperial collapse, the formulation of depth psychology and of theories of the unconscious and the attendant re-evaluation of dreams and myths, the literary experiments of Joyce, Grass, Garcia-Marquez and others, and indeed the advent of cinema itself with its potential for flashbacks, dissolves, and a surreal and dreamlike mode of storytelling—to slowly change the prevailing context of narrative reception. As one consequence, academic scholarship on the Sanskrit epics during the past half century has tended to stress their coherence and integrity of design.

Alertness to the ‘context-sensitive designs’ of Indian popular films may appear to be a tall critical order. The modes of cultural practice and bodies of literature and lore that I have identified in this essay constitute some relevant contexts; they interact with the historical, psychological, ideological, technological, and economic ones identified by others. Certainly, the more one knows of such contexts, the more one will be able to ‘see’ (and hear and taste) in a given film. The scholarly study of Western cinema appears to manifest preferences for both relatively ‘context-sensitive’ and ‘context-free’ approaches. The grand, reductive theories—structuralist, Marxist, Freudian—belong in the latter category, and though each has something to offer, the analysis of individual films, especially those that are recognised as enduringly significant, rarely relies on any of them exclusively. Yet when the critical lens is turned to a non-Western culture, sweeping theory may appear more seductive—a handy substitute for having to bone-up on a dauntingly multifaceted context.

Examples of a culturally ‘context-sensitive’ reading may be found in Rosie Thomas’ efforts to elucidate the ‘intertextuality’ of Hindi films, based on her assumption that such films are ‘always read and produced in relation to other texts and discourses—other films, mythology, popular art, gossip, and so on’[cxiv]. Her essay on Mehboob Khan’s 1957 hit Mother India shows how much such an approach, when focused on a single influential film, can reveal[cxv]. Similarly, Booth’s sensitivity to the ‘reflexivity’ of Hindi cinema, which ‘gains its primary value from the audience’s knowledge of the genre or story being performed (or referred to) and from a collective awareness of the performance as artifice’ yields surprising insights into the ‘densely layered religious, cultural and narrative meanings’ of film songs[cxvi], or the pleasurable complexity (including allusions to epic characters and situations, to other films, and to the off-screen lives of stars) of Subhash Ghai’s 1993 potboiler Khalnayak[cxvii].

In a famous essay on art and mechanical reproduction, Walter Benjamin cited the ebullient 1927 prophecy of Abel Gance that the advent of cinema would lead to the avid re-presentation of all significant cultural stories: ‘All legends, all mythologies and all myths…await their celluloid resurrection, and the heroes are pressing at the gates’[cxviii]. While studying the popular culture of pre-modern India—a society that prized the tactile act of ‘seeing’ as a medium of communication, delighted in episodic, non-linear tales that were elaborately and self-consciously framed, and regarded operatic dance-drama as the ultimate art form—it has often struck me that its heroes and heroines were indeed eagerly awaiting cinematic reincarnation. Within their profuse intertextual world, pre-modern Indian storytellers were already fond of flashbacks, lyrical interludes, surreal landscapes, and vast and crowded Cinemascopic tableaux; their language was visually intense, almost hallucinatory: screenplays awaiting the screen. A gaze that is more sensitive to Indian contexts will be better able to take in the audiovisual epics of their cinematic heirs and to savour (and critically evaluate) the rasa they offer to hundreds of millions of filmgoers.

Notes

[i] Lutze, ‘From Bharata to Bombay’, 14.

[ii]Thomas, ‘Indian Cinema: Pleasures and Popularity’,123.