The Sanskritist, novelist, translator and teacher’s brilliant exposition of the multiple connections between aesthetic, religious and erotic rapture in Indian literature narrated with relish and the author’s renowned straddling of academic acumen and intimate tone, the folk tale and the epic.

Rapture. The word reverberates sex and religion; discriminations between erotic and beatific dimensions of human experience deteriorate in the echoes of the two syllables. The etymological resonances are violent: in the beginning rapture is a seizure, abduction, enchantment, and loss of control. Although the overpowering feelings described by the term are universal, evaluations of them, the constructions of sentiments and cultural sensibilities out of the complex of sensations themselves, must differ from time to time and place to place; and those appraisals are articulated and codified in the divergent languages of those times and places. Each language has its own unique powers and uncanny magic, just as each has its own frustrating semantic limits. The English noun ‘rap-cher’ is romantic and seductive.

While I do not know of a lexically equivalent word, charged with the same evocative multivalences and affective meanings, in an Indian language,[i] I realise that it was a sense of rapture and yearning for what I imagined it might be that first drew me to India. Fantasy is implicated in all raptures, and a fantasy of India enraptured me during adolescence: I fancied that there they knew a rapture more exquisitely voluptuous than anything possible in what I perceived to be a thoroughly puritanical and profoundly vapid America. It was after all 1959, and I was a student at a Christian military high school. A copy of the Bhagavad Gita had fallen into my hands and, although I do not recall where it came from, I remember shuddering as I read a passage more stunning than anything I had ever before encountered in a book. A majestically terrifying god revealed himself to a rapt witness:

Wherever I look, I see your infinite forms, each one itself infinite in each and every form; I tremble in panic as I gaze upon the billions of blazing heads, arms, thighs, feet, and torsos, and infinite gaping eyes and mouths with sharp, horrific tusks. Ablaze, you graze the sky and the jagged teeth of your myriad incendiary mouths are the flames of the all-consuming fires of time. You lap up all worlds, suck all cosmoses into your gloriously conflagrating mouth; the dreadful rays of incandescent light with which you bristle illuminate and incinerate the universe.[ii]

Fig. 1: An erotic sculpture at the Konark Sun temple, Orissa, India.

I craved more. And since the Kamasutra was the only other Indian text of which I had heard at the time, I turned to it next and was equally, but differently, enraptured. Too embarrassed, too young, and too broke to purchase the book, and inspired by pubescent deviance, I stole a copy. Deviance lends itself to rapture, an experience that is implicitly illicit and antinomian, excessive and transgressive. Clandestinely I studied the copulatory postures represented by the Indian artists and lucubrated over the ancient text:

A horse having once attained the fifth degree of motion goes on with blind speed, regardless of pits, ditches, and posts in his way; in the same manner, a loving pair become blind with passion in the heat of congress, and go on with great impetuosity, paying not the least regard to excess.[iii]

The book evoked a world in which rapture could be easily negotiated, in which sex was free and good, and in which one could surrender to rapacious needs and raptorial longings without recriminations from parents, teachers, or the law. An exotic rapture, at once steamy and hallowed, was epitomised by a very distant and mysterious land. I ached to see the blazing god and become blind with that oriental passion. I purchased a recording of sitar music and, listening to it alone in bed late at night, bid alien ragas to carry me away.

My fantasies, raptures, and reveries are different now. Although I still have not seen god nor attempted all those positions, I have been to India and continue to be interested in the relationship between religious and erotic raptures in Indian cultural traditions. There is an ancient story that, in my mind, both distinguishes between and reconciles the two spheres of rapture—the tale of Rishyashringa and the courtesan.[iv

The Rape of the Ascetic: Erotic Experiences of Rapture

Once upon a time there was a terrible drought in the kingdom: withered branches of desiccated trees were skeletal hands reaching in supplication to heaven for rain. In fear of the famine and pestilence with which the cloudless sky threatened the world, the king, on behalf of his despairing subjects, summoned his counsellors, priests, and sorcerers to the court for advice as to what rite or magic would bring the fecundating monsoon.

One of the royal advisors responded: ‘‘There is a young ascetic in the forests of the kingdom—Rishyashringa, the son of a hermit. It is on his account that Indra refuses to give us rain. His austerities are so ardent, his asceticism so fervent, that he has sapped the sky of its waters. As long as he is immersed in his fiery yogic trances, it will not rain. He must be seduced; his chastity threatens the world. If he can be made to affirm this world, to relish sensual pleasure and spill his seed, the rains will certainly come and the earth, as land and goddess, will feel the rapture and be fertile once again. But that will be no easy task: the boy, reared from birth in the ashram, has never even seen a woman. How can he be tempted when he knows nothing of feminine charms and the transports of love? His virile chastity will not be easily broken.’’

Assembling his courtesans, the king offered a reward to any of them who might have the wiles to seduce the chaste ascetic. One beguiling lady, well versed in the fine arts and physical sciences of love, accepted the challenge and set out immediately on her mission. Hiding outside the ashram, she waited until the old hermit left his son alone to gather food for the evening meal.

When the moment came, she entered the hermitage and, reverentially prostrating herself before Rishyashringa, announced the purpose of her visit: ‘‘I am an ascetic like yourself and I wish to practice austerities with you. I want you to teach me your yogic practices and spiritual exercises, all your methods of concentration, including the meditational positions you assume. In return I shall initiate you into my discipline; I will teach you the postures in which I experience the supreme union.’’

When the young ascetic, having never seen a woman before, asked why she had two large bumps on her chest, she explained: ‘‘I am swollen there from being bitten by mosquitoes and – believe me – they itch. Would you be so kind as to scratch them and massage them with this soothing balm?’’ While graciously complying with the request, Rishyashringa noticed that there were no genitals visible through the strangely handsome mendicant’s diaphanous loincloth, and he asked the reason for it. ‘‘My penis was bitten off by a bear’’, the courtesan cunningly responded: ‘‘It hurts quite a lot. Would you please rub some of this healing ointment upon my wound? And would it be too much to ask you to kiss it and make it better?’’

The courtesan, in her pose as an ascetic, aroused such feelings of delight, such curiosity and admiration in Rishyashringa that he could not help but revere her as one of the most adept and accomplished of yogis. When he importuned her for initiation, his wish was duly granted. Sitting alone in deep yogic trance, he had experienced the rapture of samadhi before; but never had it been as overwhelmingly powerful as this. This was truly divine.

The sky began to fill with clouds, and at the very moment when Rishyashringa reached the pinnacle of his delirious ecstasy, there was a burst of rain and the earth herself trembled with the rapture of the storm.

The people of the land, grateful to their king and his courtesan, were drenched as they danced in the fields and streets, sharing in the rapture of earth, sky, and each other.[v]

Rapture. The word reverberates sex; it echoes with the ardent cries of both the victims and celebrants of desire. The word, in its respective etymological and associative insinuations of both rape and orgasm, intimates the terror of sex and the bliss of it. Its highlights accentuate the abysmal darkness inherent in all desire.

The linguistic kinship between rape (as abduction or sexual assault) and rapture (as ecstasy or passionate transport) suggests ways in which the development of our language has both served and reflected patriarchal values: in terms of actual experience, the aggressive act of rape is universally personally abhorred and individually feared, socially outlawed and collectively censured; and yet menacing masochistic fantasies of being raped are not uncommon in individuals who in no way, and under no conditions, actually wish to be raped, nor do those who have salaciously sadistic fantasies of taking another by force necessarily want to do so or to see rapists go unpunished. It is in fantasy that fears and desires are confronted and resolved, that the vexing and illicit relationship between rape and rapture is fathomed, and that the furtive alliance between pain and pleasure is revealed.[vi] Collective fantasies, moreover, are monumentalized in art: the similarity of the affects aroused by being enraptured and being raped is apparent in a comparison of Gianlorenzo Bernini’s sculptural depiction of the mystical rapture of Saint Teresa in whom the religious experience of being seized by God is portrayed as essentially erotic, and Peter Paul Rubens’ painting of the mythical rape of the daughters of Leucippus, where the martial event of being seized by an enemy is illustrated in erotic tones.[vii]

‘‘The Marriage Rite of Demons’’ (raksasa-vivaha) is a Sanskrit lexeme for rape explicated in the Kamasutra as ‘‘when a man, followed by a gang of his buddies, sees a girl in some village or in a park, kills or chases away her friends and guardians, and then abducts her.’’[viii] Rishyashringa is raped by the courtesan in the sense that, in antagonism to his dedication to austerities and in defiance of the will of his guardian, he is tricked in to sexual intercourse. He is ravished and enraptured; he loses control. The figurative being carried away in our version of the story is followed by a literal abduction in epic recensions in which the enamoured Rishyashringa follows the courtesan back to the city to pursue a worldly life in the palace of the king.

The ascetic project, with its severe austerities and the profound passivity of yoga, is, in psychological terms, masochistic. But the renunciatory life in the rural hermitage is an inversion of a voluptuous existence in the urban court where women are enamoured masochists, and men are cool, suave, and genteel sadists. ‘‘No I do not miss him and, no, my breasts do not heave,’’ a courtesan, as rendered by the seventh century Sanskrit poet Amaru, insists: ‘‘No, no goosebumps, and no, my face is not sweating. No, not at all, until that cheat, that ravishing bastard, appears. And then, yes, the mere sight of him, seizes my heart, soul, and breath away. Yes, my mind, usually so predictable, perversely experiences a beatific rapture.’’[ix] The poet uses a fundamentally religious word, ‘samadhi’, a yogic term, for the orgasmic climax of the seduction, of being taken against her will—which is to say, of being raped.

A poetic English usage of the word ‘‘rapture’’ has established an association of it, as it refers to an overwhelmingly intense pleasure, with orgasm as the climactic sensation accompanying the biological release of tumescence in erectile organs. Rapture is an erotic seizure. ‘‘In liquid raptures I dissolve all o’er,’’ moaned John Wilmot (1648–1680), the raunchy Earl of Rochester, in ‘‘The Imperfect Enjoyment’’, a poem about premature ejaculation: ‘‘[I] Melt into sperm, and spend at every pore.’’ Alexander Pope (1688–1744), echoing the same semantic condensations in his translation of Ovid’s fifteenth Heroic Epistle, ‘‘Sappho to Phaon,’’ also correlates rapture with feelings of dissolution and death: ‘‘You still enjoyed, and yet you still desired,/Till all dissolving in the trance we lay,/And in tumultuous raptures died away.’’[x]

Coinciding associations are intimated in Sanskrit literature. Amaru strings a series of phonemes into an extended and compact erotic compound: ‘‘tight-embraces-crushed-breasts-bristling-rapture-powerful-passion-swelling-feeling-girdle-skirt-slipping-faint-whispers.’’And suddenly the compound, like the string of jewels girdling the girl’s hips, is broken and there is a rapturous syllabic staccato: ‘‘No. No. Too much. No. No. No. Stop. No.’’ And then, in the moment of silence and stillness that follows detumescence, her lover wonders: ‘‘Is she asleep, or dead, or has she disappeared – dissolved, melted, absorbed into my heart?’’[xi] The prosody reflects the experience.

The rhetorical consolidation of rapture, orgasm, and death is, perhaps, rooted in physiology: ‘‘The ejection of sexual substances in the sexual act corresponds in a sense to the separation of soma and germ plasm,’’ Freud explained. ‘‘This accounts for the likeness of the condition that follows complete sexual satisfaction to dying and the fact that death coincides with the act of copulation in some lower animals.’’[xii] Freud’s analysis would have been understood by the father of Rishyashringa: the ascetic must remain chaste in order to be redeemed from death, in order to prevent a luminous spiritual rapture from degenerating into a darkly carnal one.

When the ascetic ejaculates, dark clouds suddenly burst open and release their pent-up rain onto the earth. The projected causal connection and correspondence between human interactions and natural forces that is assumed in the story of Rishyashringa and the courtesan provided the basis for a system of Indian fertility magic. Nature itself can be enraptured. The courtesan is called upon to work the very magic that the king’s thaumaturgists were unable, because of the power of Rishyashringa’s austerities, to perform.

The austerities that the young ascetic had been taught were intended to abolish the boundaries between subject and object; yoga was a mode of deliverance from everything transitory, of liberation from time and space. The courtesan’s mockery of asceticism in her presentation of sexual union as a form of yoga (and of orgasm as a kind of samadhi) is comic. And yet in India, as in Europe, the joke has been taken seriously. ‘‘Rapture’’ has been uttered and understood as a religious term linked to both love and death, thereby providing a cognitive coupling between the two. The word rings with soteriology.

The Conquest of the Courtesan: Religious Experiences of Rapture

Deep in the forest, gathering roots and wild berries for the evening meal, the father of Rishyashringa was suddenly drenched by the rain. Realising at once that the storm was a sign that his son’s austerities had been disturbed, that asceticism itself was being mocked by Indra, if not Kama, the aged renouncer rushed back to the hermitage in fear and anger only to discover Rishyashringa languorously slouched on the ground with an uncanny look on his face: the smile was at once blissful and melancholy; slight tears in his eyes betokened a joy that sorrows over its limits.

‘‘Father’’, Rishyashringa muttered with uncharacteristic wistfulness, ‘‘the most extraordinary mendicant visited our hermitage today while you were away. His rosaries and garlands were strung neither with rudraksha beads nor bones but with crystalline jewels and fragrant flowers; his hair was more braided than matted into locks entwined with golden threads and chains; the ashes on his body were aromatic powders; his loincloth was silken and diaphanous; the pot that he carried contained a delicious water, which he called ‘wine’. This learned guru was charitable with his knowledge: after I explained to him the renunciatory yogic exercises that you have passed on to me, he generously delineated and demonstrated the methods of his own spiritual discipline; and then, as one adept for another, he initiated me into his occult practices, showing me how to perform yoga, to experience union, in the most extraordinary and recondite positions. The samadhi for which we as yogis strive, came suddenly, overwhelmingly, and by force, transporting me beyond the confines of time and space. Flesh trembled as consciousness dissolved, as all ego activity was suspended, and the rapture that seized me in that moment was followed by a peace more profound than any that I have known from the meditations in which I have previously engaged. It was, I suppose, because of the sudden rains that he parted. But now, without him, I feel adrift and alone, deprived of spiritual life. I must beg for permission to leave the ashram, to renounce this renunciatory practice for the more rigorous religious discipline into which I was initiated today. I must find this holiest of holy men and follow him, devoting myself whole heartedly to asceticism under his guidance. I want to dissolve myself in the rapture that his yoga bestows.’’

The old hermit was furious with his son: ‘‘That was no yogi, that was a woman! You have been beguiled, ravished with deceits, dragged down into the mud of carnal attachment, reintrenched in the world of death. As our sacred texts warn: woman is, by her very nature, the destroyer of men. They are demons, seductresses lovely and cruel, who stalk the earth to ravage the minds and hearts of ascetics. You must do penance and make offerings to Shiva, the ever-chaste Lord of Yoga, and then, inspired by the austerities of that god, embark again in chastity upon the true eremitic path, storing your seed, burning up the illusory ego, and isolating eternal spirit from evanescent flesh. The ultimate rapture is attained through renouncing desire, harnessing the senses, controlling the flesh, and stilling the mind.’’

And Rishyashringa, driven to repentance by the words of his father, once again intent on liberation from the great round of birth and death, immersed himself in austerities. Eyes closed, legs folded, palms upward in his lap, breathing slowly and evenly, he strove to know the moment when the raindrop falls into the sea, to experience the rapture that comes with being obliterated, released, merged forever and ever in the sea of Brahman.

Rapture. The word reverberates religion; it resounds with the seraphic sights of saints and proselytes. Its meaning is inextricably embedded in the history of its Christian usage. Although the word is syncopated by theology, its sexual repercussions have repeatedly aroused the Christian soul and made it ache for what is forbidden and beyond the bounds of ecclesiastical piety. Devout minds have anxiously sought to resolve that petulant ache with mystical soteriologies or apocalyptic visions.

Saint Francis of Sales (1567–1622), while articulating the synonymy of ‘‘rapture’’ (the masculine ravissement) and ‘‘ecstasy’’ (the feminine extase), also demarcated a discrepancy between them: ‘‘Ecstasy is called “rapture” because it is by means of ecstasy that God entices us; and rapture is called “ecstasy” because it is by means of rapture that we abandon ourselves and remain out of ourselves for the sake of union with Him.’ The celebrant of the ‘sweet, gentle, and delightful seductions’’ that draw the soul to God warns that they have the power ‘‘to ravish and derange.’’ He contrasts sacred rapture with that profane, ‘‘infamous and abominable rapture’’ that is experienced if the soul is ‘‘lacking in charity or enticed by carnal delights.’’ That tempting ecstasy is perfidious, and that rapture ‘inflates rather than edifies the spirit.’ Rapture is fraught with temptation and danger—it is ferocious and predacious, involuntary and wholly disorienting. Francis could have been speaking for the father of Rishyashringa; while he indicates the analogy of sexual and religious experiences, he distinguishes sharply between them. The evaluative bifurcation is a matter of the object of eros, that object making the experience either annunciatory or condemnatory; the cause of rapture, not the sensation of it, determines its sacrality or profanity.

Rishyashringa has obstructed the rain by means of his tapas, a word originally and essentially meaning ‘heat’, but referring particularly, in the story of the rape of the ascetic, to religious austerities and zealous mortifications, the dynamics of which are understood in terms of an internalisation of the Vedic fires of sacrifice. The biological (and concomitant psychological) presumption inherent in the vocabulary is that asceticism (and chastity in particular) is a matter of augmenting and storing this fiery energy; tapas is squandered in sexual intercourse. As sexual release is experienced as a rapture, so too is the burning up of the transient ego, the release of the self from this painfully persistent round of birth and death. That is moksa, samadhi—the great release, a meta-rapture.

Saint Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), who no doubt influenced Saint Francis, and whose vulnerabilities to beatific raptures and propensities to orgasmic ecstasies have been monumentalised in our imaginations by Bernini, repeatedly noted that el rapto is essentially involuntary and absolutely irresistible; it cannot be controlled, neither hindered nor precipitated. Rapture, she confesses,

is a shock, striking quick and sharp, before you know what has happened to you. You cannot help it or yourself. It is felt as a cloud or seen as a mighty eagle, snatching you up and ascending with you on its wings. You are being carried away, raped, and you do not know where you are being taken. I must admit that this rapture terrified me at first – how could I help but be afraid when I saw my body being lifted from the earth?[xiii]

Rape, in Catholic mystical theology, provided a psychologically powerful metaphor for a certain experience of God: the soul, against will and despite motive, is abducted, stripped bare, penetrated, and utterly overwhelmed; in an unsolicited suspension of discriminative consciousness, there is a non-premeditated realisation of the way in which two can be one. This mystical salvation comes through ravishment, a result of the mission of a ravishing god, not on account of deliberate spiritual endeavours of the ravished suppliant.

The Vidarbhan princess Rukmini was literally raped by Krishna (the god who revealed himself in the Bhagavad Gita), seized and carried away. But the rape was an apotheosis: as a consequence of that violation, the woman realised her identity as the goddess; and when, on the eve of the current age of tribulation, she made his funeral pyre her own, she was transported up to heaven to enjoy a pristine, eschatological rapture.[xiv]

Protestant theologians, soberly proclaiming a complete distinction between the platonic eros and the Pauline agape, severed all affinities between profane, carnal love and sacred, spiritual love: the two were neither homologues nor analogues. Sexuality, even in its most vigorously sublimated and rigorously spiritualised form has, in Protestant theology, nothing to do with Christian love. Erotic beatitudes, no less than beatific sexual encounters, are delusory. Thus the psychological and figurative experience of being lifted up from the earth and spiritually carried away of the Catholic mystics becomes the physical and literal ascent into heaven of conservative Protestant chiliasts by means of an unimaginatively fundamentalist reading of I Thessalonians 4:16–17. In that epistle, Paul, who had himself experienced a transformative rapture on the road to Damascus, announces that when the Lord raises the dead in Christ, those who believe and are still alive ‘shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air.’ The poetic rapture that was the erotically spiritual transport articulated by Teresa became banalised (by way of a mainstream Protestant use of the term ‘rapture’ for the Second Coming of Christ) into the puritanical and paranoiac Pentecostal rapture referred to on a bumper sticker I saw recently on a ’92 Dodge Dart: ‘Warning: In case of Rapture, This Car will be Unmanned.’ Rapture remains a loss of control.[xv]

Asian mythology is no less millenarian. This is the Kali Age, the time of darkness and degeneration, and in it the Indian seer is no less apocalyptic than the prophets of Christian doom. The end is at hand: ‘Decay persists in the Kali Age until the annihilation of human beings,’ the Vedic sage Parashara announces; and the tribulation culminates in the coming of an avatar—the horseman Kalkin, like a warrior at Armageddon, will wipe out corruption, devastating all who are evil in thought or action. And following this tribulation, there will be a kind of rapture:

The hearts of humanity will become as pure a crystal; they will be awakened as at the end of night. These new perfected beings, the redeemed residue of humanity, once transformed, will give birth to those who will thrive in a Golden Age of Purity.[xvi]

There is, however, a significant difference between the Christian and Hindu cosmologies of rapture. While the former results in the resurrection of the body into a state of everlasting joy, the Indian imagination does not dare to conceive of a corporeal ecstasy that is anything other than essentially transient; the gods themselves are subject to time and death. Entropy, though reversible, will ultimately continue to reassert itself, and the Golden Age will once again yield, through time, to yet another Iron Age and another and another; as light must succumb to darkness, heat to cold, and movement to stillness, so all rapture will eventually dissipate into despair. Thus liberation from the microcosmic cycle of birth, death, and rebirth within the macrocosmic cycle of creation, destruction, and re-creation must be the ultimate aspiration of a patient Rishyashringa. Finally, he strives for the non-rapturous rapture of the immaculately transcendental peace of eternal oblivion.

In one version of the story of the yogi and the courtesan, Rishyashringa marries his seducer and she comes to live with him in the hermitage, ‘possessed by love, religiously waiting upon him and obediently serving him as loving bhakta.’[xvii] The adoring wife of the epic literature became the model for a certain kind of Indian religious sensibility, that of devotion, of bhakti. This devotion, as taught by the Bhagavad Gita and other normative texts, was initially calm, cool, and collected, rigorously controlled and hardly rapturous. But (probably through South Indian influences) a new form of bhakti developed by the end of the first millennium. This bhakti, a passionate and fiery love for god in which rapture was a symptom, a method, and a goal, is epitomised by the lovelorn milkmaids of Vraja who, intoxicated by the beauty of Krishna, fell into convulsive raptures at the mere thought of the bewitchingly beautiful deity. ‘Once our hearts were set within our homes, but then you abducted us, ravishing those hearts,’ one sings, and cries out on behalf of the group: ‘Place the cool lotus which is your hand upon our burning breasts and fevered faces.’ The amorous god lured the milkmaids away from the protection of their fathers or husbands into the forest, where,

…he embraced them, touched their hands, ran his fingers through their hair, and caressed their thighs and breasts; he aroused them by joking with them and scratching them with his fingernails. And then he made love to them... The women were intoxicated, their hearts enraptured by the way he walked, by his sexy smile and his sweet talk... Every one of them experienced the supreme rapture, the great pleasure of feasting their eyes upon him.[xviii]

In emulation of the mythical milkmaids of Vraja, a legion of medieval saints, male and female, sang of the beatitudes of love, of the rapture experienced through the grace of Krishna. One of the most renown of them, Chaitanya (1486–1533), was a prime exemplar of a state in which the experience of ecstasy comes not from the will or action of the devotee but from the sudden and surprising attack of a passionate god. It is a seizure that overwhelms the saint. Once, the hagiographer explains, Chaitanya just happened to hear the flute of a village boy and it reminded him of Krishna’s flute: ‘He was ravished by the sound and lost all sense of himself in the sacred frenzy of love. He fell on the ground and foamed at the mouth.’[xix] Throughout the hagiography, he is described as being overcome by madness, frenzy, and hysteria as he danced and sang, weeping and laughing, in holy, erotic raptures. Identifying himself with Radha (the milkmaid who emerged in poetry as Krishna’s favourite), he would, as if to lure the god, dress up as her, pretend to be her as he danced and sang passionate love songs. Then it would happen: he would lose all control, and in a spasmodic rapture, a seizure and abduction of his ego, he would become Radha, deliriously suffering that rapture as her rapture.

Fig. 2: Raja Sawant Singh and Bani Thani as Krishna and Radha ca.1760. Painting by Nihal Chand. Courtesy: Fine Arts Museum of San Fransisco.

In contrast to Chaitanya who, like Saint Teresa, remained physically chaste while being spiritually raped and emotionally enraptured, there were members of the Sahajiya cult of Bengal who believed that sexual rapture could be epiphanic, that sexual union was sacred to the degree that during it the man realized himself as a manifestation of Krishna while his consort recognized herself as Radha: ‘The essence of beauty springs from the eternal play of man as Krishna and woman as Radha. Devoted lovers in the act of loving seek to reach the goal,’ announces a Bengali song attributed to the fifteenth-century Sahajiya poet Chandidas. ‘Using one’s body as a medium of prayer and loving spontaneously is the Sahaja love.’[xx]

What was comic in the story of Rishyashringa—the boy’s innocent acceptance of sexual union as an esoteric religious discipline, a yoga leading to Samadhi—becomes suddenly serious in the Sahajiya movement as an essentially Tantric form or method of Krishnaite bhakti. While the emotional bhakti of medieval saints promised the heated rapture that comes from loving God, the ritualistic tantra of the same period affirmed the cool rapture that results from being God. There were antinomian Tantric cults in which ritual sexual union became a means of samadhi. In Tantric literature in general, however, sexual union is sacramental not as a method of experiencing rapture (in the sense that rapture implies a loss of control or a ravishment), but rather as a way of checking it, a mode of storing tapas (equated in this context with the retention of semen); it is practiced dispassionately. The Tantric adept, like the courtesan who seduced Rishyashringa, is profoundly in control. And like the courtesan, the Tantric hero has power; his sexual activity is both an expression of that power and a method of augmenting it.

The Vacillations of the King: Aesthetic Experiences of Rapture

Once upon a time there was a king named Bhartrihari who, inspired by the loveliness of the women in his harem and charmed by the manifold manners in which they applied mastery of the amorous arts to entertain him, composed songs in celebration of the exquisite transports of passion. He was a connoisseur of the beauty manifest in the flowers of the royal garden, the courtesans in the royal palace, and the poetry that was recited and the art that was viewed in the royal hall. Those women, with their flowers strung in their hair, girdled with strings of rubies, gathered to listen to that poetry:

Renounce sense pleasures’ is but a homiletic platitude,

Holy prattle from loquacious mouths that theologize;

But who on earth can adopt such a solemn attitude

And give up ruby-girded loins and water-lily eyes?[xxi]

One day an ascetic came from the forest to the palace to offer the king a wonderful gift—a strangely delicious fruit that the yogi claimed had a magical power to bestow eternal youth on the one who tasted of it. The mendicant explained that it had been given to him by a god in reward for the firmness of his chastity and the rigour of his austerities.

The king was so enamoured with one particular courtesan in his harem that he, in hopes of sustaining her loveliness forever, endowed the nectarous fruit to her. She, in turn, and for the same reason, bestowed it upon her secret paramour who then lovingly tendered it to a woman who, unbeknownst to anyone, had ravished his heart. That lady, another of the courtesans of the harem, so adored her lord, the king, that she, with a bow at once reverential and passionate, presented it as a gift to him, that he might preserve his youthful vigour and demeanour for her. The moment that he saw it, he was stricken with grief, utterly disenchanted, and wholly overwhelmed by a realisation of the inconstancy of love and the transience of all erotic raptures:

Me: I’m in love

with a woman who’s in love

with a man who’s in love

with a woman who’s in love

with me

Fuck her! fuck him!

fuck the other woman!

fuck love and Love!

And me![xxii]

In disgust and with the ambition of renouncing a life in which amorous joy is all too fragile, Bhartrihari fled to the forest and searched for the ascetic that he might return the magic fruit and find refuge in his ashram. When with perfect detachment, the holy man tossed the fruit aside, a wily monkey darted down from the tree and made off with the gift.

The ascetic initiated the king into yogic practices, taught him the ancient discipline with all the dedication that the father of Rishyashringa showed for his son. Eagerly discarding his royal robes for the scant, rough garb of ascetics, the king immersed himself in fiery austerities, embarked in chastity on the eremitic path, storing his seed, and striving to burn up the illusory ego and to isolate eternal spirit from evanescent flesh. He recited:

Inevitably the ones we have enjoyed in love,

no matter how long they have abided with us,

abandon us;

Suffering that separation, how is it that a man,

his heart so ruptured, still does not

let go of them?

If they wander off of their own,

his heart is tormented with a misery,

unequalled and infinite;

But if he lets go of them of his own accord,

the heart will realize a rapture,

serene and endless.[xxiii]

Often during his meditations, he would be assailed by memories of the palace: he pictured the smile of a courtesan, heard the tinkling of her anklet bells, and smelled, in the Malabar breezes, the fragrant sandal talc that cooled her breasts. Ravished by recollections, he could not help but return to his palace. Memory (Smara) is, after all, one of the many names of Kama, the harassing god who is love.

Back in the world, once again taking women of flesh and blood into his embraces, it was not long before he realized that it was his own imagination, his fantasies as a poet, that had prompted him to abandon the ashram for the palace:

‘Lips like rubies, teeth like pearls’

describes the oral orifice of girls;

‘Hair like flax and alabaster skin,’

Describes scalp and hide that’s feminine;

‘Limpid pools,’ describes just eyes:

ideals made up of poet’s lies,

Ugliness turned into beauty

out of some artistic duty.[xxiv]

Once again the king sought refuge in the forest. Eyes closed, legs folded, palms upward in his lap, breathing slowly and evenly, he strove to know the moment when the raindrop falls into the sea, to experience the rapture that comes with being obliterated, released, merged forever and ever in the sea of Brahman. But on the brink of that oblivion, he suddenly felt a need to visit the palace once more, to say good-bye to those who had given him the pleasure, despite the transience of that delight:

Back and forth he went between the palace and the ashram—seven times in all—ever torn between sensual indulgence and ascetic renunciation:

In this world, passing, insubstantial, ever changed,

There are two ways in which one’s life may be arranged:

There is piety, austerities, and devotion,

Overflowing with a nect’rous knowledge of high truth;

No? Well, then pursue another sort of emotion –

And touch with lust that part hidden, low (and uncouth),

Within the firm laps of women prone to pleasure,

Loving ladies with warm thighs and breasts beyond measure.[xxv]

Perched in the branches of a tree in the ashram, the monkey who had filched and devoured the magic fruit could not help but burst out with laughter over the poem and the irresolute king who recited it.

While in the ashram, nostalgic for the erotic rapture of love, the king authored amorous songs; while in the palace, missing the yogic rapture of Brahman, he wrote verses on renunciation. But all in while, in both realms, he composed poetry, finding his ultimate solace in the delectable rapture of poetry itself, in a transcendent world created in, by, and as art, a sublime kingdom entirely free from the constraints of reality and not dependent on anything but itself.[xxvi]

Rapture. The word reverberates religion and sex; and those reverberations are established, heard, and reconciled in the figurative manipulations of language that constitute poetry.

The Sanskrit poet was called kavi, a word that originally implied a priestly seer, gifted with insight and a holy voice in which he could, by the power of his magical praises, invoke and confront sacred forces within and without. The Sanskrit word for ‘poetry’, ‘kavya’, is a qualitative rather than a formal or stylistic term, describing any work of prose or verse that is infused with a particular and conventionally delineated rasa, an aesthetic flavour, mood, or sentiment. Innately abiding like instincts within the human heart, according to the theorists, are basic emotions such as love, merriment, sadness, courage, anger, fear, and so forth. In the theatre or literary text (or, implicitly at least, in other art forms, including painting and sculpture), the affects and effects of these emotions may be represented in such a way that they are transformed or enhanced to precipitate an aesthetic experience, a rasa, in the heart of a spectator, reader, or viewer. That sublime rasa could be fully savoured, it was argued, only by people who, through many births and diligent study, had cultivated a capacity to take a transcendental pleasure in the universality of the sentiment. They were the rasikas, literary gourmets, who relished the good taste of poetry, the flavour produced through a harmonious blending of lovely images, melodious words, and majestic ideas. They were tastefully dispassionate rapturists.

There were Indian aestheticians who equated the experience of the rasika or connoisseur with that of the yogi or ascetic, and correlated the pure experience of a poetic sentiment with the religiously idealised experience of the oneness of the ineffable Brahman as the absolute ground of existence. The aesthetic moment was understood as a sacred one, a rapture, an eternal instant in which one was seized, carried out of oneself, utterly transported. Art sanctified the world.

The twelfth-century critic Mammata argued that poetry has the power to engender a world that is ‘free from the constraints of reality, uniformly rapturous, and not dependent on anything but itself.’ Poetry, he held, can bestow the ‘immediate realization of a transcendent rapture.’ In the moment that the rasa is tasted, he asserted, ‘everything else falls into oblivion and one feels as if one were experiencing the absolute rapture of Brahman.’[xxvii] A work of art, like the magical fruit presented to king Bhartrihari, can, through its delectable taste, redeem us from the confines of time and space. Disparities between the erotic and the religious evaporate in the heat of rapture. Dissolution is the resolution and absolution.

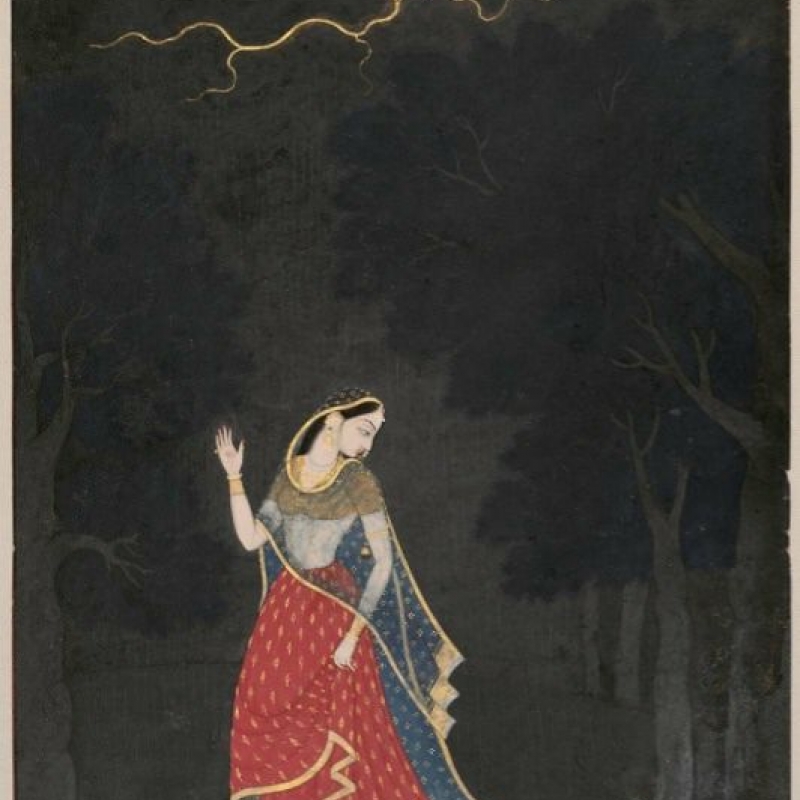

I return to the memory, revived by the invitation to write this essay, of being an adolescent, lying in bed alone, late at night. Listening to the sitar music and the sound of rain, I was seized by fantasies. A teenage imagination conjured up by an Indian god with terrifying manifold mouths, tusked and gaping, each one a blazing furnace that beckoned with incendiary promises of a frightening yet tempting eternity. I saw the smile of a girl in the fire, a young Indian girl from one of the erotic miniatures in the book I had stolen; she was, no doubt, as ravishingly beautiful as the courtesan who initiated the youthful Rishyashringa into the mysteries of sexual love. Overwhelmed, as surely anyone on the threshold of adulthood must naturally be, with melodramatic anxieties about death and love, I got out of bed and tried to write a poem by candlelight. It was, most likely, pretentious and self-indulgent, awkward and, no doubt, sensationally sentimental. I cannot recall the words scrawled on the page, but I do remember that it was about that imaginary oriental god and girl. And I remember what it was called – ‘Rapture.’

Endnotes

[i] There are no convincing cognates in the Sanskritic branch of the Indo-European languages for the Latin raperelraptus. The Sanskrit words I have translated as ‘rapture’ are words for an intense joy that point in the divergent semantic directions coalesced in the English term. Words such as samadhi, nirvrti, and ananda have strong religious and soteriological resonances, while harsa, priti, and rati stress the essentially erotic nature of pleasure. Vaman Shivam Apte’s Student’s English–Sanskrit Dictionary, offers both harsonmada (a ‘joyous madness,’ suggesting love and sexuality) and anandatireka (an ‘excess of bliss,’ implying an ascetic or devotional religiosity) as equivalents of the single English word. My colleague George Tanabe has explained to me that in Japanese (following the Kenkyusha New Japanese-English Dictionary) there are two terms for ‘rapture’: one, kyoki, like harsonmada, means ‘crazy joy’; the other, uchoten ni naru, a Buddhist term literally referring to ‘being taken up to heaven’ (much like the Pentecostal Christian use of ‘rapture’), has come to be used metaphorically for secular experiences of extreme delight, as ‘being ecstatic over one’s success.’

[ii] Bhagavad Gita 11.16–30, paraphrased in keeping with the way I remember it on that first reading long ago.

[iii] Kamasutra 2.7. This is Richard Burton’s translation, the one I read as a teenager. The equine metaphor aptly illustrates the way in which rapture is a loss of control.

[iv] For an insightful discussion of the story of Rishyashringa, see O’Flaherty, Asceticism and Eroticism, 42-52. The name Rishyashringa, meaning ‘Antelope-Horn,’ was given to the boy because he had a single horn growing on his head; he was the offspring of a hapless female antelope who happened to drink water into which an ascetic (the boy’s father) had accidentally (and non-rapturously) spilled his semen. Having had no human mother, Rishyashringa did not experience the pleasure of contact with a woman even as an infant at the breast. Regression to that early phase of ego-feeling, before the infant has learned to distinguish his or her own ego from the external world, was, incidentally, the way in which Freud (in Civilization and Its Discontents [1930]) analysed the religious rapture that Romain Rolland, after his experiences in India, had called the ‘oceanic feeling.’ (See The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, 64-65.) I have relied, in my retelling of Rishyashringa’s story, primarily on the versions in the epic Mahabharata and the Buddhist Jatakas.

[v] The mosquitoes and the bear appear in the Nalinika Jataka renders the Pali passage into Latin (perhaps on the assumption that persons disciplined enough to know Latin would be sufficiently self-controlled not to be ‘carried away’ by the words of the courtesan).

[vi] Lynn S. Chancer, in a sociological discussion of rape fantasies, has explained their frequency in women in terms of ‘the feminine gender socialization producing a relatively greater tendency toward masochism. At least through a masochistic fantasy, pleasure can be permitted, if only because guilt has been neutralized by a situation in which the masochist is no longer responsible; and the masochist expiates the sin of pleasure through the simultaneous experience of punishment. Given double standards of sexuality for men and women in patriarchal societies, and their legacy of shame, guilt, and repression for women about their sexual feelings, it is not in any way remarkable that such fantasies among women would be common’ (Sadomasochism in Everyday Life, 58).

Sadomasochism was codified into a fine art with its own exacting conventions in the chapters of the Kamasutra that deal with biting, scratching, and slapping (2.4, 5, 7), methods, Pandit Vatsyayana explains, both to intensify and express the sexual rapture he illustrates with the analogy of the horse galloping out of control. The very concept of rapture suggests the way in which the potencies of pleasure are enhanced by a lacing or spiking with pain.

Rape is, incidentally, an extremely common motif in modern Indian films, movies produced to satisfy the fantasies of a largely male audience; the majority of that audience have, or will have, arranged marriages—a form of matrimony that is, in the sense that the will or desires of the bride are irrelevant, an institutionalised form of rape.

[vii] The rape of the daughters of Leucippus by Castor and Pollux, like the rape of the Sabines, was socially justified as necessary to populate an emerging society. The liturgy of later Roman marriages re-enacted the rape of the Sabines: the groom pretended to seize and carry off his bride, festively to rape her, much to the pleasure, or even rapture, of them both; our own custom of the groom carrying the bride across the threshold may well be an atavistic remnant of that rite.

‘Every lover who falls in love at first sight,’ Roland Barthes has reflected, ‘has something of a Sabine Woman (or some other celebrated victim of ravishment)’ (A Lover’s Discourse: 188). The French word for rape, ravissement, gives, I think, equal semantic weight to both the desired and dreaded implications of the experience. Barthes’ equation of rape and love at first sight (enamouration), is well understood in Sanskrit literature: ‘When loving glances first afflict the heart and passions grow ardent,’ the poet sings, ‘then even to wander there on the road near her house is a rapture more sacred than that of making love’ (Amarusataka, 100). (This and all other translations that follow, unless otherwise noted, are my own.) I would want to go further than Barthes, to suggest that every lover, male or female, anyone who feels either a desire or a pleasure that is not control-

[viii] Kamasutra, 3.5.

[ix] Amarusataka, 84.

[x] The most common Sanskrit words for orgasm (ksobha and samvega) indicate shaking, agitation, paroxysm, flurry, and (explicitly in the case of the word uttapa) a boiling over or an eruption. The pleasure of rapture is an apoplectic and malignant one. An Ayurvedic doctor I interviewed in India in 1985 (for a book on comedy), explaining to me that epilepsy was a form of sexual dysfunction, interpreted the Sanskrit term for epilepsy (apa-smara [which probably has to do with forgetfulness]), as ‘a reference to Smara, the god of sexual love.’ Galen in the second century, in On the Affected Parts, made the same correlation between the sexual act and epilepsy, between orgasm and convulsion. There was, by the way, an interesting shingle outside the office/shop of Indian doctor: ‘Specialist in Women and Other Diseases.’

[xi] Amarusataka, 40. Cf. 101: ‘As my beloved came to bed my robe slipped loose of its own accord the skirt barely clung to my thighs that is all I remember now once we touched I could not know who he was who was I and how much less our love.’

[xii] Freud, The Ego and the Id, 47.

[xiii] Saint Teresa of Avila, Vida de Santa Teresa de Jesús, 20.3, 7, 9 (my emphasis).

[xiv] Hrta, the participle used in the text (Visnu Purana, 5.26.6), like the Latin raptus, means ‘seized,’ ‘taken away’; the narrowing of the meaning into ‘rape’ comes with the author’s reference to the act as the raksasa-vivaha (5.26.11).

[xv] The year of the Dodge is not insignificant: it was in 1992 that the evangelical Mission for the Coming Days actually made headlines with their announcement that the apocalyptic rapture was, absolutely without a doubt, imminent. A pamphlet published by that group in February of that year of our Lord, using biblical references to compute the exact time and date of the event, ends with a prayer that ‘each and every one of you will serve and love our Lord Jesus until the time of the Rapture, 24:00 of 28 October 1992, and then join us to meet the Lord in the air.’

[xvi] Visnu Purana, 4.24.25–29

[xvii] Mahabharata

[xviii] Bhagavata Purana 29.34, 41, 46; 30.2; 32.9. Throughout the text, verbal forms that refer to being seized, abducted, transported, i.e., raped (grhita, apahrta, aksipta) are used. Nirvrta is the word I have translated as ‘supreme rapture.’

[xix] Kaviraja, Caitanya-caritamrta, 151-52); my rendering follows the rough translation of Nagendra Kumar Ray

[xx] Chandidas, translated by Deben Bhattacharya in Love Songs of Chandidas, 105. 82

[xxi] Srngarasataka of Bhartrihari 71, 147. Three collections of poetry—one a set of moral maxims (nitisataka), one a century of erotic poems (srngarasataka), and one an anthology of stanzas on renunciation (vairagyasataka)—have been attributed to him. I have used the editions of both W.L.S. Pansikar and that of Kosambi.

[xxii] This stanza (311 in the Kosambi edition), a seemingly late addition to the Bhartrihari collection, is no doubt the seed of what was to become this legend.

[xxiii] ‘The ones we have enjoyed’ is for visaya [h], which included not only people but all objects of enjoyment. ‘Rapture that is serene and endless’ is for sama-sukham anantam, which the commentator (in the Pansikar edition) glosses as the ‘highest bliss’ (paramananda) and explains : ‘The happiness of love is worldly, the greatest happiness is divine; it is the result of the peace that comes by giving up desire’ Vairagyasataka 12 (Kosambi 157)

[xxiv] I have taken the liberty of using English clichés for Sanskrit ones. Literally rendered, the stanza is far more condemnatory: ‘The bulbs that are her teats are compared to golden pitchers; her face, that receptacle of sputum, is compared to the hare-marked moon [as receptacle of the nectar of immortality]; her thighs, putrid with dribbles of piss, are said to rival elephants’ trunks. Thus a form that is disgusting is made delectable by various poets’ (Kosambi 159).

[xxv] Srngarasataka 37

[xxvi] The legends considerably postdate the actual historical Bhartrihari (mentioned by the Chinese pilgrim I-tsing in his seventh-century account of Buddhist India); my sources include the Vikramacarita, and the Bhartrharinirveda of Harihara.

[xxvii] Kavyaprakasa of Mammata, 1, 4. Poetry, and art more generally, has, by the lies it tells and the illusions it creates, the potential to redeem us from our suffering even if it is that very suffering that is depicted or celebrated in the poem or work of art. In his ‘In Memory of W.B. Yeats,’ W.H. Auden speaks of the poet who ‘Sing[s] of human unsuccess/In a rapture of distress’ (my emphasis).

Bibliography

(Amarusataka. [Bombay: Nirnaya-Sagara Press, 1900.] 100)

‘Jataka 526’. In Nalinika Jataka, (526. in the edited by V. Fausbǿll. edition [London: Trūbner, 1877–96.]);

Apte, Vaman Shivam. Apte’s Student’s English–Sanskrit Dictionary., 3d ed. (Pune: Motilal Banarsidass, 1920.)

Barthes, Roland. Barthes A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments., Ttranslated by. Richard Howard. [New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1978.], 188)

Bhagavata Purana. (Bombay: Nirnaya-Sagara Press, 1910.)

Bhartrihari. Srngarasataka. of Bhartrihari 71 (Edited by D.D. Kosambi. critical edition, 147)

Chandidas, translated by Deben Bhattacharya in ‘Chandidas’. In Love Songs of Chandidas, The Rebel Poet-Priest of Bengal. Translated by Deben Bhattacharya. (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1967.) 105. 82

Freud, Sigmund. Freud, ‘The Ego and the Id’ (1923) in The Standard Edition, vol. (19), (1961)., 47.

Harihara. Bhartrharinirveda. of Harihara (Bombay: Nirmaya-Sagara Press, 1892).

Harihara. Bhartrharinirveda. Bombay: Nirmaya-Sagara Press, 1892.

Kaviraja, Krishnadasa. Caitanya-caritamrta. of Krishnadasa Kaviraja (Calcutta: Gaudiya Math, 1958.) (Madhyalila 18. 151-52)

Kaviraja, Krishnadasa. Caitanya-caritamrta. Translated bytranslation of Nagendra Kumar Ray. (Puri: Sri Sri Chaitanya-Charitamrta Karalaya, 1959).

Kenkyusha New Japanese-English Dictionary. Tokyo: Kenkyusha, 1954.

Lynn S. Chancer, Lynn. (Sadomasochism in Everyday Life. [New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1992.], 58).

Mahabharata. (Pune: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.)

Mammata. Kavyaprakasa. of Mammata (Pune: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1965.)

Nalinika Jataka (526 in the V. Fausbǿll edition [London: Trūbner, 1877–96]); the standard translation of E.B. Cowell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1895–1907)

Nalinika Jataka. Tthe standard translated bytion of E.B. Cowell. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1895–1907.)

O’Flaherty, Wendy Doniger. O’Flaherty, Asceticism and Eroticism in the Mythology of Siva. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972.)

Saint Teresa of Avila. , Vida de Santa Teresa de Jesús., Eedited by. Fr. Diego de Yepes. (Buenos Aires, 1946. ) 20.3, 7, 9 (my emphasis).

Strachey, James, trans. (See The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. (21). , trans. James Strachey [London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-analysis, 1964.], 64-65.

Vatsyayana. Kamasutra. of Vatsyayana (Bombay: Nirnaya-Sagara Press, 1900. ) 3.5

Vikramacarita. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1926.) and the

Vikramacarita. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1926.

Visnu Purana. [Gorakhpur: Gita Press, n.d.] 5.26.6

The reproduced text appears in full in Negotiating Rapture: The Power of Art to Transform (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 1996, 18 – 33). © 1996 Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. All rights reserved.