In this magisterial essay, Namita Gokhale and Dr Malashri Lal review the sweep of linguistic and literary cross currents that rode on the waves of trade, war and religion throughout South Asia. Looking back from the first decade of the 21st century, the authors stress the process of accretion and enrichment as existing literary cultures were overlaid by other flavours through such interactions. Pico Iyer elaborated on this moment in his celebrated essay, ‘The Empire Strikes Back’ describing it as ‘a call to free spirits everywhere to remake the world with imagination’, and open up ‘a new universe by changing the way we tell stories and see the world around us.’ The authors range over the linguistic tapestries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka before tagging the dazzling diversity of India’s contemporary literary heritage. Importantly, this essay contextualises the folio’s focus on the seemingly sealed Sanskrit rasa theory as one of many aesthetics practices still followed today.

Note: This essay was first written and published on the occasion of the Jaipur Literature Festival, 2015.

South Asian literature, in its many voices, languages and avatars, retains an underlying warp and woof of cultural connectivity. Each country of the Subcontinent has its own political and emotive narrative and its own unique stories to share. Linguistic histories, colonial experiences (or resistance to them), and traumas such as Partition and conflict have fermented and matured the writing of each country and society. The Empire left—but left its language, literature and genres behind. The phrase, ‘A language is a dialect with an army and a navy’ first came into use via the linguist Max Weinrich. In a linguistically diverse set of cultures, the Queen’s English asserted a hegemonic sway.

While Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) was a watershed that impacted how the world viewed South Asian writing, the author’s magical prose also transformed the way this writing looked at itself. Although some critics categorised it as a valorisation of the ‘post-colonial exotic’, Pico Iyer’s famous essay ‘The Empire Strikes Back’ described it as ‘a call to free spirits everywhere to remake the world with imagination’, opening up ‘a new universe by changing the way we tell stories and see the world around us.’ The voice of Saleem Sinai, Rushdie’s main character, reclaimed the spoken sounds of the Bombay streets into English literary usage. The sinuous stylistic flow also reflected the texture and grain of Urdu, which is an important part of Rushdie’s literary inheritance.

The Urdu tradition, in the footsteps of Saadat Hasan Manto and Faiz Ahmed Faiz, mirrored both a determined social commitment and a strong sense of comic subversion. Pre-Partition Urdu was a secular, agnostic language, one capable of both the most brutal irony and the highest romanticism. It was used by Munshi Premchand, Rajinder Singh Bedi and Krishna Chandar, by Qurratulain Hyder, Ismat Chughtai and Ghulam Abbas, in the syncretic linguistic tradition of Urdu/Hindustani. Post-1947, Hindi was shorn of its Urdu and Hindustani traces and influences, and was immensely the poorer for the loss. During the 1950s, as Pakistan entered into cycles of military domination, restrictions on free expression led to a heightened sense of symbol and metaphor. As Faiz Ahmed Faiz wrote,

If the bloodied pen has been snatched from my hand,

I will bear the sorrow

and dip my fingers in the blood of my heart …

Today, however, Pakistan is witnessing a brilliant blossoming of talent in its highly visible international English-language writers. From Zulfikar Ghose, Bapsi Sidhwa and Sara Suleri, a new generation of names come quickly to mind—Kamila Shamsie, Mohsin Hamid, Aamer Hussein, Nadeem Aslam, Mohammed Hanif, M.A Farooqi, Daniyal Mueenuddin and H.M Naqvi, among several others. In the words of the novelist Kamila Shamsie, ‘Pakistani writing is like the new young fast bowler on the scene.’ Daniyal Mueenuddin observes that ‘there is an edginess in our writing ... which is distinctive.’

In the City by the Sea (1998) by Kamila Shamsie

Other national literatures of Pakistan, such as Sindhi, have retained a distinct voice despite being marginalised for various reasons. Sindhi literary traditions date from the heroic ballads of the 15th century, but politics and geography suffered a disconnect in 1947. A recent session at the Jaipur Literature Festival (co-founded by this writer) on Sindhi writing attempted to bring together Pakistani and Indian Sindhi authors, with Bhagwan Atlani, Shaukat Hussain Shoro and Vimmi Sadarangani celebrating their common language.

‘My own country’

A similar weave of plurality continues in Nepal, when views of and within the country are refracted through both Nepali and English. Writer Manjushree Thapa has observed:

In the 1990s and before, members of Kathmandu’s cloistered literary establishment – almost entirely ‘high caste men’ would write Kathmandu-based literature; and only a few regional writers who had won recognition from the establishment would write about their particular communities … there were women writers but they had to battle for tokenistic representation from their male peers … A few writers published commentaries, literary or otherwise, in the newspapers. The rest of Nepal remained almost wholly unwritten. This insularity had become quite untenable by the time the war started [in 1996]; and yet it persisted until the war’s end.

The iconic Indra Bahadur Rai, who writes in Nepali about the Gorkhali/Nepali community of India, lives in Darjeeling. Ramesh Vikal, Govind Bartaman and Narayan Wagle, among others, are articulating new social and national realities, in Nepali. Manjushree Thapa, Samrat Upadhyay and Rabi Thapa, author of the recently published Nothing to Declare, are part of the ‘global local’ community in their use of English and their outreach to local, regional, diasporic and international readers. At the same time, the traditions of oral, epic and folk poetry carry on in another living stream as well, as modern poets find sustenance from these sources.

Nothing to declare (2011) by Rabi Thapa

Bhutan too exhibits the same ambiguous relationship between English and the official national language, Dzongkha. Hagiography, religious texts and commentary are still widely written in sonorous Dzongkha, a language based on old Tibetan and made official only during the 1960s, which struggles to balance the gravitas of administrative and religious prose with the compulsions of modernity. The Queen Mother Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck’s engagingly written Treasures of the Thunder Dragon: A portrait of Bhutan (2006) has opened an interesting new window onto this evolving democracy. Authors such as Kunzang Choden (who has been translated into 14 languages) look both to the past and future through their fiction; Kinley Dorji and Sonam Kinga—from the viewpoints of a bureaucrat and a newly elected politician, respectively—reflect upon their own changing society, while Karma Ura’s The Hero with a Thousand Eyes has already achieved near-classic status, spanning as it does the transition from another era. As in many countries of the region, meanwhile, the Internet has unleashed a generation of blogger-writers, and a new wave of current and spontaneous expression will surely follow.

Treasures of the Thunder Dragon: A portrait of Bhutan (2006) by Ashi Dorji Wangmo Wangchuck

Bangladesh continues its tryst with the Bengali language, radical and mellifluous in the same breath. The intense shared heritage of the Bengal renaissance and its aftermath illumines the work of scholars, academics and writers in both Bengali and English. Ghulam Murshid has written about, edited and annotated the legacy of a crucial writer such as Michael Madhusudan Dutt. The Bengali firmament shines with legendary writers and poets such as Syed Shamsul Huq, Shamsur Rahman, Humayun Ahmed and Muhammed Zafar Iqbal, as well as younger names such as Shaheen Akhter. Global outreach, meanwhile, is articulated by writers including Monica Ali, Tahmima Anam and Shazia Omar.

Sri Lanka has followed a slightly different template. An extraordinary array of international talent, such as Michael Ondaatje, the Sri Lankan-born Canadian author, Romesh Gunesekera and Roma Tearne (who now live in Britain), has drawn literary inspiration from Serendip. Carl Muller lives in Sri Lanka and has produced a major body of work; Shehan Karunatilaka’s debut novel, Chinaman (2011), has also drawn great acclaim. These authors’ writings often lead back to a conflicted racial and linguistic struggle, where the distances and angers between Pali, Sinhala and Tamil literature have yet to find common ground and mediation. The ancient tongue of Pali continues to be used in religious matters in the predominantly Buddhist island. Sinhala is an Indo-Aryan language with distant roots in Sanskrit, a deep classical tradition and a considerable output in multiple genres, with writers like K Jayatilaka and Siri Gunasinghe. Tamil, meanwhile, shares a legacy with mainstream Indian Tamil literature and its long history and aesthetics. Tamil poets and writers such as Kasi Ananthan, Jayapalan and Cheran give voice to the bitterness and tragedy of war and mass killings, yet reach out with hope and conviction, with their writing retaining a dynamic connection with other contemporary Tamil writers in Tamil Nadu.

Chinaman (2011) by Shekhar Karunatilaka

The cultural flow between West Bengal and Bangladesh continues unabated. It is no surprise that the bonds of food and music, the commonality of folk songs and ballads, proverbs and metaphors, run deeper than politics, ideology and religion. Only recently, Tahmima Anam spoke in Kolkata of the sense of belonging she felt there, of how ‘despite the barriers, [there is] a deep shared history’. Sugata Bose, author of the new His Majesty’s Opponent: Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle against Empire, similarly said of his recent book launch in Dhaka, ‘I felt like it was my own country … and now Tahmima’s book launch in Kolkata in a way complemented that experience.’

1792 mother tongues

And so we come to India, that paradox of paradoxes, where the same patterns of linguistic unity and diversity show up as in many other of the region’s countries, but on a completely different scale. India’s complex realities and contemporary narratives are built on a template of continuity and change. Little is ever abandoned or forgotten in India, with the river of history carrying nearly everything along in its meandering pace.

With 22 official national languages, 122 regional languages, four classical languages (Sanskrit, Tamil, Kannada and Telugu) and, according to official sources, 1792 mother tongues and countless dialects, the diverse and polyphonic expression of literary identity in modern-day India is both daunting and inspiring. Although colonisation and the imposition of English stifled the vitality and outreach of many Indian languages, today, after decades of suppression, writers are increasingly turning again to their own tongues, with new creativity and inspiration.

The various bhasa-language clusters in India are distinctive, yet share a common heritage and core identity. Grassroots writers in the many languages of India have both a contemporary voice and an enduring connection with classical traditions—here it is essential to mention the Hindi, Bengali, Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, Marathi, Odiya, Assamese, Punjabi and Urdu traditions. Novels, short fiction, poetry and experimental writing are flourishing in each of these, along with a robust practice of literary criticism. English is an Indian language, of course, and the first language for many writers from the states of the Northeast. English also serves the critical function of a link language for literary translation and so, ironically, is important in the forging of a common literary identity.

The novel is not a homegrown literary form, but has adapted instinctively to South Asian climes. The first modern Indian novel, Indulekha, was written by Chandu Menon in Malayalam in 1889. Novelists such as Srilal Shukla, Uday Prakash and Alka Saraogi in Hindi; Mahasweta Devi and Sunil Gangopadhyaya in Bengali; Ambai, Sivasankari and Ashokamitran in Tamil; U.R. Ananthmurthy in Kannada and M.T. Vasudevan Nair in Malayalam are just some of the great and beloved names in modern Indian literature.

India’s two most enduring epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, inform both the folk (desi) and classical (margi) traditions. As the famed Kannada writer U.R. Ananthamurthy has noted, ‘there are two languages that are understood all over India – the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. One can easily refer to the characters from these epics, and [these] make sense to anyone.’ This inter-textuality connects nearly all Indian literatures and also illuminates translations, adaptations and film versions of mythic and folk material.

Similarly, mythology remains a constant on Indian bestseller lists. The engaged examination and reinterpretation of enduring epics within different languages and genres is often surprising to Western minds, which tend to categorise myth as a static and closed area of study. But the gods are alive in India and much of the rest of the region: mythology is not a merely academic subject, but a topic of vital and immediate relevance. The complex cultural, political and religious attitudes of ‘modern’ India cannot be understood without an understanding of its myths and their impact on the collective faith of many of the country’s communities. The interaction between the ancient heroic stories and contemporary writing has yielded an outpouring of essays, plays, films and novels, including the hugely popular The Palace of Illusions (2008) by US-based Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, the Ramayana series (2003-06) by Ashok Banker, the chart-busting The Immortals of Meluha (2010) by Amish Tripathi, Chanakya’s Chant (2010) by Ashwin Sanghi, and In Search of Sita: Revisiting Mythology (2009), which I co-edited with Malashri Lal.

Many of India’s Adivasi and other marginalised societies, for long mistakenly described as ‘illiterate’, are repositories of oral literatures that have been transmitted through generations. Timeless ballads and folk epics are often processed into the mainstream imagination, but in that process many face the dilemma of being forgotten, of being distorted in translation or of losing their fluidity and being embalmed through academic archiving. For example, Ghafaruddin Mewati is a balladeer of an unbroken secular tradition dating from the 18th century, when the Muslim composer Sadullah Khan appropriated the Hindu Mahabharata tradition for his own poetic ends. Today, Mewati’s young grandson, Shahrukh, is the enthusiastic recipient of this heritage, but it is doubtful whether he, or others like him, will be able to sustain it.

Meanwhile, Indians both in their homeland and in the diaspora have achieved an intimate ability to use English in an Indian context. Arundhati Roy, Vikram Seth, Amitav Ghosh, Kiran Desai and others are notable international writers with deep Indian roots, while V.S. Naipaul and Salman Rushdie acknowledge their ‘Indian-ness’ despite their differing circumstances of birth, history and geography. Author and journalist Tarun Tejpal talks about his long struggle to find an acceptable voice and tone for his fiction:

For an Indian author it is not always easy to write in English. The English language represents the character of the people it was born out of – it is a language of understatement, reserve, and coolness. But the Indian reality is anything but that – it is noisy, emotional, overheated, anarchic, swinging pell-mell between rationality and irrationality.

Transformational

Many marginalised and suppressed voices, those of Dalits, women and others, are using their newly emergent micro-literatures to subvert oppressive hierarchies and prejudice. Women writers in particular are having significant and growing impacts on the literary traditions of India’s many languages, even in the face of resentment from an established patriarchal set-up. In July 2010, the vice-chancellor of Mahatma Gandhi International Hindi University, Vibhuti Narain Rai, created a furore by referring generically to Indian women writers as ‘chinals’, or prostitutes, for writing more about their ‘physical rather than spiritual’ experiences. Such an extraordinary statement created a major controversy and divide in the Hindi-literature world, with quite a few male writers rising in defence of Rai’s statement—and many others openly expressing their outrage. In the South Asian context, fiction provides a surrogate space for women, as for writers of alternative sexualities, allowing them to discuss and honestly wrestle with their identities in a still largely patriarchal, homophobic society. The same trend impacts other aspects of ‘gendered’ writing, A. Revathi’s The Truth About Me: A Hijra Life Story (2010) being a memorable example of this.

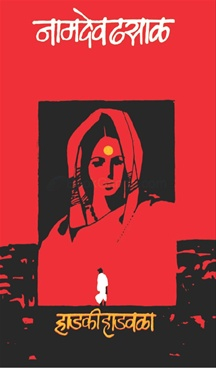

During the 1960s and 1970s, Dalit writers from Maharashtra such as Baburao Bagul and Namdeo Dhasal were the first to aggressively employ ‘transformational literature’ to transgress established lines of caste and custom. In so doing, they successfully created a new chorus across all the Indian languages, one that spoke of hope and assertion. At one level, the Dalit writing movement is the militant assertion of a class struggle, a Black Panther-style movement; indeed, Dhasal took specific inspiration from the African-American movement, starting the Dalit Panthers in 1972. Along the way, there has also been a tremendous outpouring of hurt, pain and, eventually, catharsis.

The modulation of this transformative writing from a record of pain to an assertion of change is a moving graph of literary power. Caste and community are sensitive issues in India and throughout the region. Every category feels badly treated and victimised by others, so there is endless potential for provocation, anger and conflict. The Dalit readings and panels at the Jaipur Literature Festival last year discussed the rejection of mainstream Indian literature and the assertion of an alternative sensibility. Despite the inherent politics and propaganda, there were also people weeping in the audiences; the raw pain and hurt in the readings came as something of a revelation to some cocooned middle-class mindsets.

Hadki Hadawala by Namdeo Dhasal

There was also tremendous media attention, in India and internationally, focused on these Dalit writers and issues. One of the major ideologues of the caste struggle, Kancha Ilaiah, wrote a moving editorial piece in the Deccan Herald, ‘literary festivals teach how to connect oneself to social mass culture, if one is doing transformative writing. If it helps even a section of oppressors to identify with the viewpoint of the oppressed, writing becomes more meaningful.’ In India, where many feel so passionately about the country’s multiple literatures, such festivals provide a crucial space for society to share problems—and anger is a very important part of the process. Indeed, I do not know where else in the world so much anger is associated with literature. But this is valuable, because it is a thinking anger, a talking anger, rather than a stone-pelting anger. At South Asian literature festivals today, there is a buzz in the air, crafted by the passionate enthusiasm and curiosity of people who are trying to figure themselves out in the midst of change and challenge.

The Queen’s Hinglish

Language and identity have still not been flattened out in our region, but the process of confrontation between ‘Globish’ and disappearing local languages and dialects is an ongoing one. A new pan-Indian language, cousin to colonial English, is currently emerging in both literary and popular spaces, and ‘Hinglish’, the merging of English and Hindi, has its own literary identity. Writers such as the British-Indian poet Daljit Nagra write in a phonetic mix of Indian English that challenges the mind and the ear, as in ‘Look we have coming to Dover!’:

Imagine my love and I

and our sundry others, blared in the cash

of our beeswax’d cars, our crash clothes,

free, as we sip from an unparasol’d table

babbling our lingoes, flecked by the chalk

of Brittania

Like most of South Asia, modern India exists in a constant state of translation. While inhabiting a spontaneous and accepting multilingualism, it is rarely self-conscious of this plurality. The Kannada writer U.R. Ananthamurthy says, ‘I cannot live in only one language. I live in English, I live in Kannada, I live in Sanskrit, and in so many translations.’

After many millennia of complex stratification, our region is breaking out into an individuated understanding of itself. This offers an opening for stereotypes and propaganda to be refuted, for women to be given new spaces, for people from suppressed communities and backgrounds to struggle for equity and equal opportunities. There remains an immense amount of suffering and corruption and cynicism, of course, but it is a new world still, fighting for its voice through different languages and literary traditions. This is not happening in one voice, because in South Asia we would never speak in one voice; rather, it is taking place as a jugalbandi, where people perform together in classical structures that are improvised from moment to moment.

Over the last six years, the unprecedented growth of the Jaipur Literature Festival has led me to conclude that this phenomenal success was fuelled by an acute need for a space of simultaneous interpretation of the contradictory, often conflicting realities of India and South Asia. Jaipur as a platform for the shared South Asian languages, such as Urdu, Nepali, Bengali and Tamil, has led to even more engaged levels of debate on literature and society in much of the region, fractured by political identities but conjoined by language, culture and history.

In South Asia, then, the literary space is beginning to look at its own reflection—in its own mirror, rather than viewing itself in the refracted approval of an imagined Western audience. The publishing industry is growing at an unprecedented rate, with a combined population of more than a billion potential readers and a vibrant homegrown information-technology industry. And somewhere between these many vibrant languages, interpreting and re-interpreting themselves, there exists a unity of critical appreciation that comes through shared aesthetic and critical methodologies.

It is a unique privilege to be in the eye of the storm of this literary re-exploration of one of the most ancient and continuous cultures in the world. The love of books, the vitality and passion to write in the unique texture and contours of the Subcontinent—these things are illuminating today’s literary life. It is an extraordinary time to be writing, and to be reading.

The radical Punjabi poet Lal Singh Dil wrote,

When the labourer woman

Roasts her heart on the griddle

The moon laughs behind the tree.

The father amuses the younger one making music with bowl and plate

The older one tinkles the bells

Tied to his waist and he dances

These songs do not die

Nor either the dance in the heart

And indeed, these songs do not die.