Known variously as the Harappan Civilisation, Indus Valley Civilisation, and Indus Civilisation, the period between c. 2700 -1900 BCE in undivided Northwest and West India represented the Bronze Age phenomenon of the Indian subcontinent. The region witnessed an economic and socio-cultural efflorescence manifest in urbanization, monumentality, use of a script, class stratification, and diversification and intensification of socio-economic activities that have come down to us in the form of eloquent ruins, artefacts, and artefactual remains. The terracotta repertoire uncovered from these sites, especially the terracotta human figurines, is also an evocative testimony of the times. Do the figurines codify and depict the memory – methods and meaning – of a bygone era? It is the human-ness of these figurines and the opportunity to unravel past usage patterns that has continuously drawn archaeologists and other scholars to them. Scholars in search of remote antiquity have tried to see them as precursors of our times and the genesis point of all things enduringly South Asian. Others have tried to see in their human likeness, a reflection of their own times. Both approaches are tricky prospects, given that the script has not been consensually deciphered or contexts unambiguously ascertained.

The beginning of terracotta production in South Asia can be traced to the aceramic or pre-pottery levels of the site of Mehrgarh in Baluchistan, Pakistan, dated to around 8th-7th millennium BCE. The earliest terracottas were crude handmade unbaked clay figurines. The transition to baked clay or terracotta can be seen from the later layers of occupation at the site of Mehrgarh itself, dated to c. 5th millennium BCE. The Harappan terracottas can genealogically be placed within a larger ambit of terracotta production and the products of the period of the First Urbanization continued some earlier trends of manufacture and usage and simultaneously produced unique and typically Harappan forms.

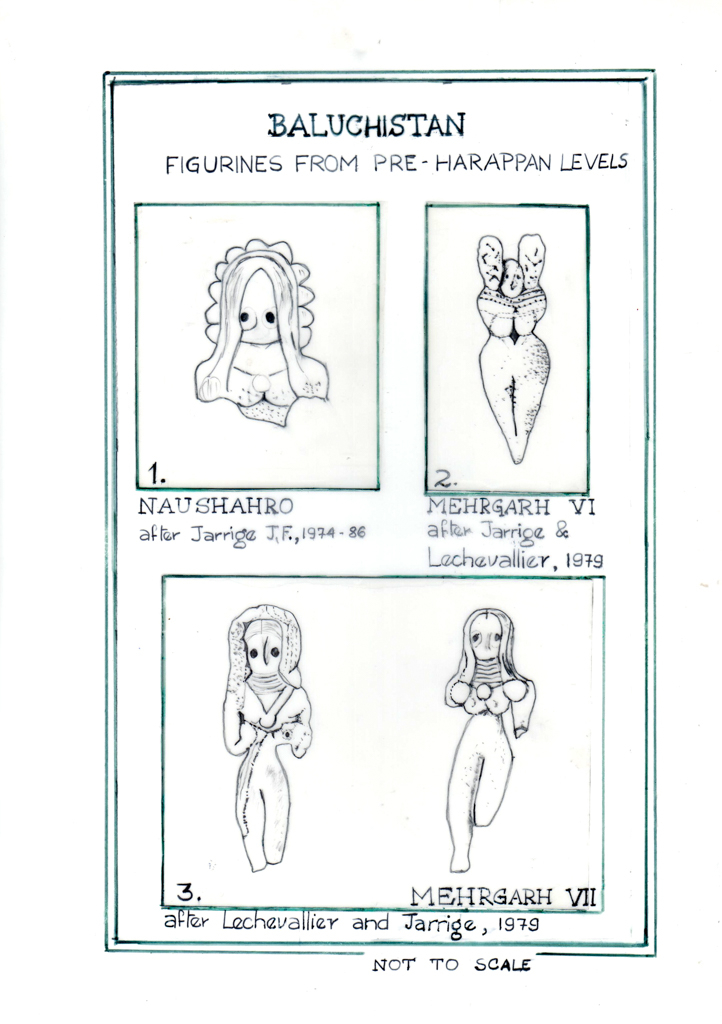

Fig. 1: Sketches of Pre-Harappan terracotta figurines from Nausharo and Mehrgarh, Baluchistan

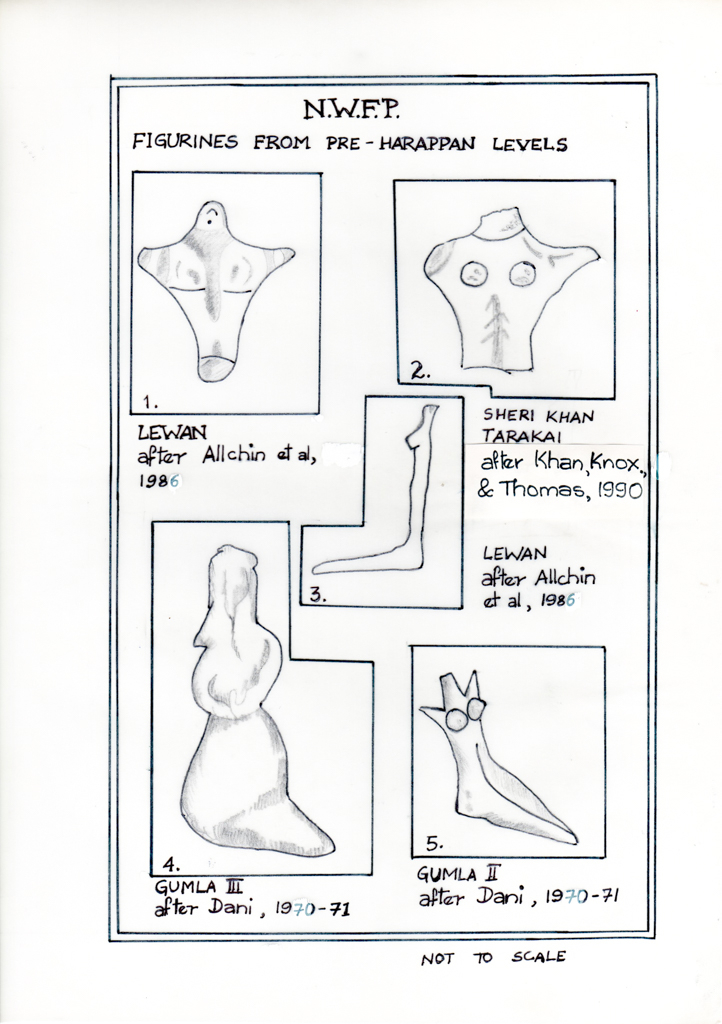

Cultures pre-dating and sometimes contemporary with the Harappan culture, from the same larger geographical zone – such as Mehrgarh, Zhob, and Kulli cultures in Baluchistan; Bannu and Dera Ismail Khan sites in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (formerly NWFP – North West Frontier Province) and relevant finds from Jalilpur, Sarai Khola and Harappa in Punjab – have yielded a plethora of figurine types. These figurines vary in form. For e.g., writing about the earliest figurine find, the excavators, M. Lechevallier and G. Quivron report – Period I represents the aceramic Neolithic level and though no pottery was found, familiarity with clay is attested by the presence of artifacts such as small unbaked containers and even a human figurine with a rounded base and a conical body on which a belt is applied. The terracotta corpus begins from Periods IV and consists of seated armless tubular figurines that acquire arms and ornamentation over time but curiously remain with their legs tied. The Kulli figurines end at the waist and are described as having a ‘scared hen’ like appearance whereas the Zhob figurines are pedestalled and have a fierce ‘skull-like countenance’. The earliest terracotta finds from Lewan in Bannu are seated, with elongated stick shaped heads, raised arms and well modelled busts. Terracotta human heads from Sheri Khan Tarakai are all roughly cylindrical with prominent pinched noses. Three individual terracotta figurine fragments were thought to be noteworthy – a ‘horned deity’ type, ‘snake goddess’ and a hermaphroditic figurine. The Gumla terracotta finds are divided on the basis of legs, bent or straight and those holding a tray. The excavator, A.H. Dani suggested that the later terracotta figurines could be a seated figurine or a standing cobra. The pre-Harappan assemblage from the Punjab sites has been compared to material from Gumla and Sarai Khola and those, especially from Harappa, have been delineated on the basis of manufacturing techniques employed and ornamentation applied.

Fig. 2: Sketches of a Pre-Harappan terracotta figurine found at Lewan, Sheri Khan Tarakai and Gumla, North West Frontier Province.

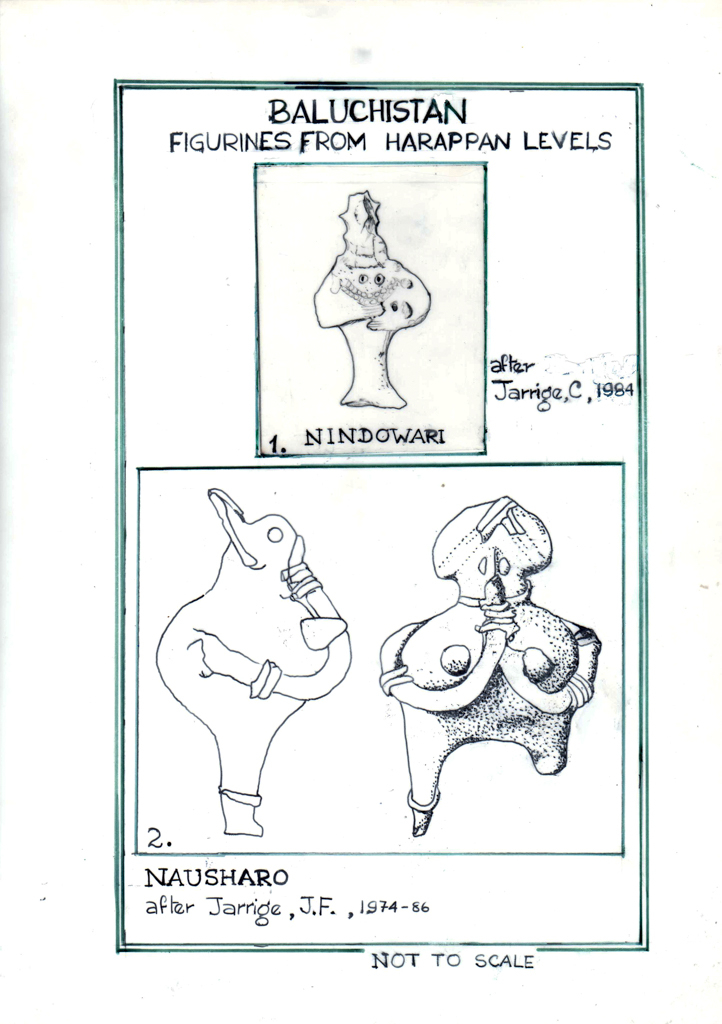

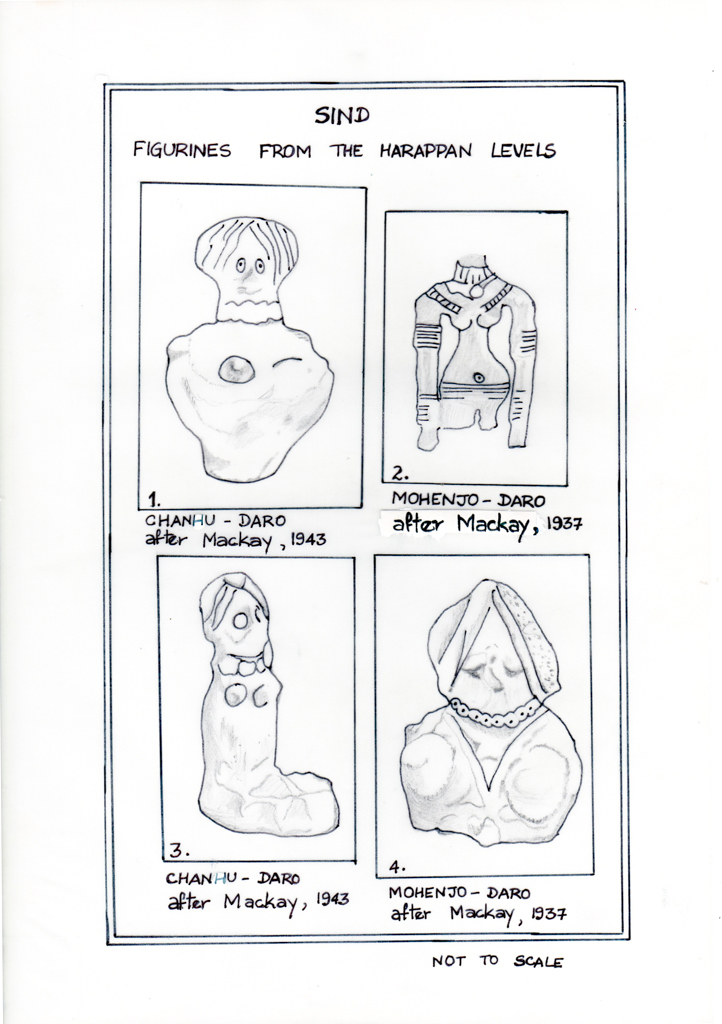

The precedential diversity in terracotta production continued in the Harappan period. Admittedly, the numbers of animal forms in terracotta outnumber the humanoid types. For e.g., D.P. Sharma’s work on the Harappan Terracottas in the National Museum collection gives a list of 77 human terracotta, including masks, in a list of 283 terracottas. Thus, they form less than one-third of the collection. But even that limited number makes apparent the vividness in form, production methods employed, and tentative usage. The male figurines include masks, horned masks or puppets, double-headed human figurines, male busts, nude male figures, standing male, seated male/ human figurines in yogic posture and seated human figures with clasped hands/in namaskar pose. The typical Harappan female figurine in terracotta is a semi naked, thin waisted, wide hipped statuette with conical breasts, wearing a loincloth and girdle, fan-shaped headdress with pannier like appendages, and heavily adorned with jewellery. This type has mostly been classified as the ‘Standing Mother Goddess’. Other types consist of standing females, short potbelly mother goddess, pregnant animal-headed female, standing females with typical headdress, seated female grinding grain, seated working woman, lying mother and child, female torsos, female heads, pot belly female suckling baby or suckling two babies, and potbellied monkey-faced seated mother goddess. The descriptions are supposed to be self-explanatory and no rationale or criteria is provided for the varied description of even similar looking figurines.

Out of the over twelve hundred sites discovered so far, only sixty have gone under the archaeologist’s spade and the occupation pattern varies from place to place. The problem of paucity gets compounded by the lack of detailed descriptive and contextual information available for systematic Excavation Reports have been published for only a very few sites. A survey of the geographical distribution of the Harappan terracottas complicates a simplistic assessment of this artefact type. The areas of Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa have yielded rich data from their dry and rugged terrain for the Early Harappan, Mature Harappan and Late/ Post Harappan periods. Terracottas have been unearthed from sites in Sind and Pakistani Punjab, more prolifically for the Mature Harappan period. But only stray and single digit terracotta finds are attested from Harappan sites in India, such as Rakhigarhi, Banawali, Kalibangan and Dholavira, from the Mature Harappan and/ or Late Harappan levels.

Fig. 3: Sketches of Pre-Harappan terracotta figurines from Zhob, Mehrgarh and Damb Sadaat

Fig. 4: Sketches of Harappan period terracottas from the sites, Nindowari and Nausharo

The contextual analysis of terracotta figurines is also rife with problems. The issue of a lack of detailed description alluded to, for distribution pattern, is reflected here as well. The reports of early terracotta finds were in the reconnaissance and survey trips of scholars like Aurel Stein, who conducted hurried and haphazard excavations and often found the figurines as stray finds or in pits, cinerary urns and generally unstratified locales. Terracotta figurines have been gathered more abundantly from rubbish pits, open areas, yards, drains, burial deposits, with other broken small items from Harappan streets and domestic contexts, and more scarcely from remains of monumental buildings. Their relative absence from large, imposing ruins hints at their consumption pattern as a commodity and lack of ritualized consecration indicates a humbler status than so far attributed to them.

Fig. 5: Sketches of the terracotta figurines form Chanhu daro and Mohenjo daro

The technology of terracotta production has not been gleaned from any in situ kiln or remains of a potter’s workshop but through reconstructions based on ethnoarchaeology and studies of the techniques of terracotta art of later periods by art historians like S. Kramrisch, A.K. Coomaraswamy and P.L. Gupta and more recently through close scrutiny and X-Ray analysis by the American Archaeological Mission at the site of Harappa. Most of the figurines are handmade and were baked in kilns, along with pottery, thus acquiring the typical terracotta reddish appearance. The decoration and surface treatment were undertaken after the figurine was satisfactorily ready for such application.

The process of terracotta production began with the essential first step of the preparation of clay to be used, i.e., its appropriate selection and cleaning. An analysis of the clay used in pottery as well as terracotta objects led E.J.H. Mackay to remark that the soft, blackish clay of the tank or river, which had been underwater for some time, was preferred because of its pliability. This clay was kneaded several times for pulverization and then degraissants were added for better effectiveness. It is presumed on the basis of studies of pottery that degraissants like sand, mica, and lime were used as binding and tempering agents, to prevent the cracking or warping of the figurines during the baking procedure. Overall it seems that the natural properties of the clay were put to good use, for pottery and terracotta production alike.

The prepared clay was then given a desired shape through the dexterous use of human hands at the pre-firing stage. Objects were dried in the sun and then put in round domical kilns with perforated floor for baking. The shape of the kiln and perforation ensured uniform heat and oxidation. Subsequently, the painting or slip and decoration occurred. Most of the Harappan figurines are solid, handmade terracottas though a few hollow figurines and partially wheel thrown terracottas have also been discovered. V. Tripathi and A.K. Srivastava have surmised for the hollow terracotta figurines found at Mohenjo daro and Chanhudaro that they were fashioned using the coiling technique wherein the clay was kneaded and then coiled spirally to form the body of the figurine. The hollowness was achieved by thumbing out the clay from the coiled roll. Interestingly, the hollow figurines are without legs and generally pedestalled. Alternatively, Tripathi and Srivastava suggest that the bulbous, roundish looking bodies of these figurines may have been acquired through the use of the wheel and other parts were later shaped and luted to the body. Moulded terracottas, mostly masks, were made using wooden moulds that have not survived the ravages of time.

An unusual manufacturing detail was observed by the American Archaeological Mission in their recording of the terracottas recovered at Harappa during the 1989 season of work. ‘Attention is now being focused on the manufacturing procedures used for the figurines as well as on their types and styles. A peculiar manufacturing detail has been recognized for the female figures. Most, if not all, were made in vertical halves which were stuck together before the jewelry, other ornamentations, and hip bands were applied. Careful examination of complete figurines usually detects traces of the join on the torso’ (Dales and Kenoyer 1992:64). Three basic decoration techniques were used extensively – pinching the clay between fingers, to depict facial features; applique, for the shaping of eyebrows, lips, breasts, and sometimes eyes – involved separately formed parts being stuck together while the figurine and the appliqued parts were still wet; and incision technique, for ornamentation and hair treatment.

Given that a lot of thought, design, and technical finesse went into the making of these figurines, the questions that beg to be asked are – who were the makers of these figurines and why or for what purposes were they made? Do we treat them as commodities for consumption, as part of some ritual paraphernalia or as specimens of art? Were they intentionally made to be mobile carriers of meaning that was embedded in their form and appearance? All these frameworks entail envisaging larger socio-economic and socio-cultural matrices within which these products were made, used, and viewed.

Within the discipline of archaeology and cultural anthropology, figurine studies have evolved into a separate sub-field, which enmeshes methodologies deriving from the study of gender, sexuality, ritual, identity, and childhood. Earlier scholarship tended to subsume all figurine finds, especially of female figurines, as goddesses. The manufacture of terracottas coinciding with the advent of food production was seen as being symptomatic and representative of a belief system based on fertility – the fertility of the earth as generator par excellence and female fertility being ensconced in these tiny terracotta representations. The ‘Mother Goddess’ hypothesis was challenged by P.J. Ucko in 1968 when he submitted that it was unlikely that the figurines served the same single purpose, aspect or deity and urged for a distinction between sexual symbolism of Mother Goddesses and the sexless group being dolls. The floodgates of interpretation were subsequently opened and figurine studies across the world moved further from ‘a fertility icon’ lens to readings that are contextualized and nuanced.

This slight digression on the older and emerging analytical frameworks of terracotta figurines was taken to intentionally juxtapose it to the paucity of such rigorous interpretation for the Harappan terracottas. The figurine debate, it seems, has left South Asia almost unaffected. Over the past nine decades, numerous figurine finds have been reported from various prehistoric and protohistoric sites. But the analysis of their meaning and usage is staid and the Harappan figurines are, academically speaking, anachronistic creatures, trapped in the era of the Mother Goddess.

The story of the Mother Goddess appendage goes back to the time of the initial excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo daro. Reflecting the prevalent academic trends of his time, John Marshall contended that the semi-nude, fan-shaped headdress wearing figurines were probably goddesses ‘with attributes very similar to those of the Great Mother Goddess, 'Lady of Heaven', etc., and the special patroness of women whose images are found in large numbers at so many early sites in Elam, Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Eastern Mediterranean area’ (Marshall 1931, rpt. 1973:339). He mentioned other terracotta female figurines too – a woman suckling a baby, women holding utensils, steatopygous figures etc. But these were overlooked, a victim of scholarly oversight, and a supposed profusion of Mother Goddesses captured the imagination of the people.

E.J.H. Mackay, who excavated the sites of Mohenjo daro and Chanhu-daro, also functioned within this broad framework and according to him, the jewellery laden, fan-shaped headdress wearing figurines were deities which represented ‘an Earth-or Mother-Goddess, the two titles were synonymous in some ancient cults’ (Mackay 1938:258). However, he could not conceive of a reason for the pannier-like receptacles being used as lamps. ‘Lamps are, of course, commonly burnt before images in India and elsewhere, but I do not know of such a practice as using part pf the image itself as a lamp being recorded anywhere’ (Mackay 1938:260). M.S. Vats’ monograph on the excavations at Harappa had an identical interpretation for the terracotta female figurines from Harappa. Mortimer Wheeler believed that there was an exaggerated tendency to regard the terracotta females ‘as a manifestation of the Great Mother Goddess’ but did not dismiss the belief altogether.

According to W.A. Fairservis, the terracotta females along with other symbols were part of a fertility-related cult, which initiated the contemporary Harappan into the complexity of his/her religious phenomenon. F.A.R. Allchin and B. Allchin recognized that the terracotta figurines could be either toys or cult objects, or both, but the Mother Goddess suffix continued. They endorsed Marshall’s conclusion ‘that the great number of female terracotta figurines were popular representations of the Great Mother Goddess’ and agreed with the parallels he drew between this evidence and the ubiquitous cult of goddesses, and particularly that of Parvati, the spouse of Siva, both throughout modern India and in Indian literature (Allchin & Allchin 1982: 213-14). Jim Shaffer posited religion as an interaction sphere in the context of which the terracottas had circulation and meaning ascribed. A hypothetical association of the Zhob figurines as Mahadevi, wife of Siva was suggested (Shaffer 1978: 148). In his comprehensive work on the Indus Civilization, Gregory Possehl has suggested that figurines being the most intimate insight into the life and people of the Indus Age, their diversity perhaps reflects the multiethnic composition of Indus society (Possehl 2002: 120).

Art history witnessed an almost simultaneous study of Indian terracottas. A.K. Coomaraswamy was the first to shed light on the issue and delineated a number of descriptive details for the bird or animal-faced human figurines from Peshawar classified as archaic. Stella Kramrisch broadly divided Indian terracottas into two categories – the ageless/timeless type which persisted over the centuries, essentially changeless and the timed variations that result from impresses which the passing moment leaves on them. The ageless types, beginning with the Harappan specimens, were the work of either man or nature whereas the timed variations were mould-made. She opined that the images of the Great Mother predominantly constituted the timeless variety and the barest allusion to her feminine appearance sufficed or could be dispensed with altogether. She believed that the material of the ageless type – earth – contributed its own fictile nature to the symbolism (Kramrisch 1994: 69-71).

Catherine Jarrige’s work on Mehrgarh and other Baluchi sites has exposed the frailty of distinguishing gender on the basis of elaborate coiffure and other hairdos and the absence of specific locations or special settings with which these figurines could be associated. Alessandra Ardeleanu Jansen’s Qualitative-Quantitative Assessment of the terracotta figurines of Mohenjo daro revealed the rarity of female figurines at the site and their uneven distribution in the various sectors. These insights led her to infer that they were not equally significant for all the inhabitants, were not involved in any hypothetical Acropolis-related cult activity and were less important in the post-urban phase. She thus proposed a revision of the ‘Mother Goddess’ theory which would be congruent with the facts of the matter i.e. the scarcity of female figurines outside the Greater Indus Valley and their debatable prominence at Mohenjo daro itself (Ardeleanu-Jansen 1992: 5-14).

As per Shubhangana Atre’s work ‘The Archetypal Mother’, the female terracotta figurines are representations of the vestal virgins in the cult of goddesses like Diana. Atre postulates the virgin status on the basis of a ‘few noticeable features: the short skirt around their waist, their full grown but not pendulous breasts and the attenuated waist’. The soot marks on the cup-like appendages attached to the fan-shaped head-dresses were preserves of the sacred fire in the Harappan households (Atre 1987: 197). P.V. Pathak has entirely refuted Atre’s hypothesis of the existence of the Diana cult in Harappan times. Anachronistic and irrelevant cross-cultural comparisons apart, he stressed the fact that the terracotta female figurines in the Indus civilization were neither Mother Goddesses nor virgin goddesses but were toy dolls for young girls and that the Mother Goddess cult as practiced in the West probably did not exist in the Indus culture (Pathak 1991-92: 60).

More recent analyses of terracotta figurines include Sharri Clark’s work where she has tried to deconstruct the Mother Goddess hypothesis based on her intensive scrutiny, cataloguing, and assessment of terracottas unearthed in the last few seasons of work at the site of Harappa. To this must be added, the remarkably new insights provided by Ajay Pratap in his attempt to bring terracottas within the purview of the reconstruction of, and archaeology of childhood.

Any artefactual analysis, especially of material objects of a civilization whose script remains enigmatic, is derived from and should be admitted as being speculative and conjectural. As scholars and academics, the tendency is to define and delineate but this imposes a fixity on material things that might be mobile, multi-faceted, and with multiple uses. Terracotta figurines can be likened to traces or signposts of the past, which can be better understood if the light from numerous windows of interpretation is shed on them. Otherwise, the terracottas will be like the fabled elephant, with blinkered scholars only reading them from their own limited vantage points.

(Inserted sketches of terracotta figurines, recovered from some Pre-Harappan and Harappan sites, are done by the author)

References

Allchin, F.R. and B. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ardeleanu-Jansen, A. 1992. ‘New Evidence on the Distribution of Artifacts: An Approach Towards a Qualitative-Quantitative Assessment of the Terracotta Figurines of Mohenjo-Daro’, in South Asian Archaeology 1989: 5-14.

Atre, S. 1987. The Archetypal Mother: A Systematic Approach to Harappan Religion. Pune: Ravish Publishers.

Bhardwaj, D. 1998. Investigating the Archaeology of Female Figurines in North-West India (upto c. 200 B.C.). M.Phil thesis. Department of History, University of Delhi.

--------------- 2004. ‘Problematizing the Archaeology of Female Figurines in Northwest India’ in Archaeology as History in Early South Asia, eds. Ray, H.P. and Sinopoli, S., pp 481-504. New Delhi: Aryan International and Indian Council of Historical Research.

Clark, S.R. 2007. Representing the Indus Body: Sex, Gender, Sexuality, and the Anthropomorphic Terracotta Figurines from Harappa’. PhD thesis. Department of Anthropology, Harvard University.

Dales, G.F. and Kenoyer, J.M. 1992. ‘Harappa 1989: Summary of the Fourth Season’, in South Asian Archaeology 1989: 57-67.

Dani, A.H. 1970-1. ‘Excavations in the Gomal Valley’, in Ancient Pakistan 5: 1-177.

Fairservis, W.A. 1971. The Roots of Ancient India. New York: Macmillan.

Jarrige, C. 1984. ‘Terracotta Human Figurines from Nindowari’, in South Asian Archaeology 1981: 129-34.

Jarrige, J.F. 1986. ‘Excavations at Mehrgarh-Nausharo’, in Pakistan Archaeology 10-22: 63-131.

Kramrisch, S. 1994. ‘Indian Terracottas’, Exploring India’s Sacred Art. Selected Writings of Stella Kramrisch, ed. B.S.Miller, pp 69-84. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.

Lechevallier, M. and Quivron, G. 1981. ‘The Neolithic in Baluchistan: New Evidence from Mehrgarh’, in South Asian Archaeology 1979: 71-92.

Mackay, E.J.H. 1938. Further Excavations at Mohenjodaro. 2 vols. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

-------------- 1943. Chanhu-daro Excavations. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Marshall, J.M. 1931, rpt. 1973. Mohenjo daro and the Indus Civilization. 3 vols. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Pathak, P.V. 1990-91. ‘The Lady of the Beasts or The Lord of the Beasts. A Reappraisal’, in Puratattva 21: 57-64.

Possehl, G.L. 2002. The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Lanham: AltaMira Press.

Pratap, A. 2016. ‘The Archaeology of Childhood: Revisiting Mohenjo daro Terracotta’, Ancient Asia 7:5, pp 1-8.

Shaffer, J.G. 1978. Prehistoric Baluchistan. Delhi: B.R.Publishing Corporation.

Sharma, D.P. 2003. Harappan Terracottas in the collection of the National Museum. New Delhi: National Museum.

Stein, A. 1931, rpt. 1982. ‘An Archaeological Tour to Gedrosia’, in Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No. 43. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Tripathi, V. and Srivastava, A.K. 1994. The Indus Terracottas. Delhi: Sharada Publishing House.

Ucko, P.J. 1996. ‘Mother, Are You There?’, in Cambridge Archaeological Journal Vol. 6, No. 2: 300-304.

Vats, M.S. 1940. Excavations at Harappa. 2 vols. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

Wheeler, R.E.M. 1947. ‘Harappa 1946: The Defence and Cemetery R-37’, in Ancient India 3: 58-130.

-----------1968. The Indus Civilization. Supplementary Volume to the Cambridge History of India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.