Contextualizing the cultural route

Sitting in 2018, at a time when Kashmir is most often a prefix to the word ‘problem’, synonymous with conflict, and described as the ‘flashpoint of violence’ in the South Asian landscape, it is not easy to comprehend the circumstances of Mahatma Gandhi’s words: ‘While the rest of the country burns in communal fire, I see a shining ray of hope in Kashmir only.’ Peace in Kashmir now exists either in distant memory or in a long anticipated future.

In the days that immediately followed the Partition though, Kashmir had navigated the turbulent territories of violence well, unlike the states of Punjab and Bengal that were worst affected by the Radcliffe Line. It also remained far less scarred by strife as opposed to some landlocked states such as Hyderabad and Junagadh that tried, however unsuccessfully, to maintain autonomy in an attempt to neutralize religious differences alienating a majority of subjects from their rulers.

But eventually Kashmir too had to face a dilemma. At the time of the Partition, Kashmir was governed by the Dogra Dynasty of a Hindu Rajput lineage, who ruled over subjects of whom nearly 80 per cent were followers of Islam. Demography apart, what appeared to tilt Kashmir’s scales in favour of joining the Union of Pakistan, much to the consternation of the then maharaja—Maharaja Hari Singh—was the physiographic contiguity that enabled this merger. But as the final decision ultimately lay in the hands of Hari Singh, it was also deemed equally plausible that he would join the secular Union of India rather than be a part of the Islamic entity of Pakistan. However, the Indian National Congress’s growing intimacy with Kashmir’s popular leader and Hari Singh’s rival, Sheikh Abdullah (who had initiated the Quit Kashmir agitation aimed at dethroning Hari Singh only a year prior to the Independence) antagonized this probability as well. Hari Singh decided upon autonomy, a decision that Kashmir was at peace with. But neither this peace nor the state of independence was destined to endure.

As refugees began to cross the border and arrive in Jammu, bringing with them distressing tales of atrocities faced in Pakistan, Hindu and Sikh extremists retaliated in Jammu region by massacring Muslims, with the estimate of people killed and displaced varying from report to report between 50,000 and one 1,00,000, and between 2,00,000 and 3,00,000 displaced. While it is contested whether this massacre and subsequent forced migration of Muslims from Jammu to Pakistan was abetted by the Maharaja or not, these events set to motion a chain of reactions and sowed the seeds of unrest that plague the state till date. It was allegedly in response to this brutality against Muslims that a tribal army recruited from its north-western provinces was deployed by Pakistan down the Muzaffarabad–Baramulla route into Kashmir to overthrow Dogra ruler Hari Singh. During this attack the tribal militia, also called as Qabailis, killed many people, mostly Hindus and Sikhs, and even looted many villages and towns.

In the bloodshed and chaos that ensued, the maharaja, with his limited resources, was left with no alternative but to seek military assistance from India and propose an accession. Accepted provisionally against an impending endorsement by the people of Kashmir and the appointment of Sheikh Abdullah to the government, The Instrument of Accession was formally signed on October 26, 1947.

In the days that followed, the United Nation’s Commission for India and Pakistan was set up and the Resolution 47 passed in April 1948, calling for Pakistan to withdraw from Jammu and Kashmir, and India to minimize military presence, to secure an environment where the plebiscite could then be held. However, these preconditions to plebiscite were never met on accounts of India being unwilling to be held at the same category as Pakistan, whom they deemed as aggressors, Pakistan denying accountability on matters of patronizing agitations that they deemed natural reactions of the indigenous population against an incompetent maharaja, the unresolved fate of Pakistani-controlled Kashmir, and mistrust between the two countries preventing either from withdrawing forces. The situation was further problematized with the observation that UN’s decision was possibly coloured by the Cold War politics and also led to the rejection of US citizen and past fleet admiral of US Navy, Chester Nimitiz, as plebiscite administrator by India. Many more attempts at reconciliation since, the fate of Kashmir remains as irresolute.

In the absence of a conclusive decision and in the face of diminishing autonomy, dissatisfaction grew in the people, sometimes spilling over in the form of protests, but more often resulting in a longing for freedom. At the peak of insurgency, as nostalgia surrounding the idea of a free Kashmir reached its zenith, its population looked back upon the many dynasties of rule to fixate on the Chak reign as the last time Kashmir was free before, one by one, the Mughals, the Afghans, the Sikhs, the Dogras and finally the Indian government took over and controlled Kashmir. It is this same idolization of freedom that resulted in a tendency in Kashmiris to demonize the Mughals as pioneers in a cycle of domination that they now deemed as precursor to the current state of unrest.

Therefore, it is through this prism of the current political scenario that one must now observe the history of Mughal Imperial Road. Clearly, it is not only our understanding of history that helps us analyse our present but inversely, our analysis of our present also helps us understand history better as well.

Polarized culture, politicized heritage

Azaadi. Independence. Sovereignty. Autonomy.

These are key words that have dominated the Kashmiri vocabulary for more than 70 years now, reaching their zenith of popularity in the 1990s. The idea of a free Kashmir that these words represent is the same idea that has equated the Mughal rule as a dark chapter in Kashmir’s history in public conception. Half baked and abetted by divisive political agendas as this idea is, it has led people to react adversely to the Mughal Road heritage as a harbinger of foreign aggressors, even as other cultural assets introduced by these same deemed invaders continue to be celebrated consciously or unconsciously in the daily life of Kashmiris, be it as language, artistic traditions, or built heritage in the form of forts and pleasure gardens. The fact that the Mughal Road lacks access, identification, delineation, research, interpretation, and is missing altogether from education and awareness only alienates it further.

In November 1586, Yusuf Shah Chak, widely hailed now as ‘the last independent king of Kashmir’ was defeated by Akbar’s Mughal army, under the command of Qasim Shah, in Shopian. Kashmir was not directly ruled from Delhi until the reign of Shah Jahan when from an erstwhile part of Kabul Province, Kashmir was segregated as an individual provincial entity.

Even though the first road widening activity happened to facilitate Akbar’s journey to Kashmir, it was during the reign of Jahangir that the Mughal Road received maximum attention and attained its full glory. Jahangir is known to have undertaken the journey through this road more than ten times, often accompanied by Empress Nur Jahan and her brother Asif Khan. Not only did they develop Kashmir as a recreational destination with the production of the many pleasure gardens such as Shalimar, Nishat, Achabal, Verinag, etc., but they also contributed to the architecture and infrastructure of travel as well as helped with the construction of caravanserais, towers, gateways, bridges, and retaining walls along the Mughal Road, which passed through the key sites of Gujarat, Kotla Arab Ali Khan, Bhimber, Jhangar, Nowshera, Narian, Chingus, Rajouri, Fatehpur, Thanamandi, Surankot, Buffliaz, Noori Chamb, Chandimurh, Poshiana, Peer ki Gali, Aliabad, Lal Gulam, Suh Sarai, Dubjan, Shopian, Heerpur, Shadimarg, and Khampur Sarai enroute Lahore to Srinagar.

According to the Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, when a royal or noble entourage moved down the road, residents from adjacent settlements celebrated the event by lining the path, beating drums, and cheering the Mughal regime. In the far-flung hamlets, where the contemporary tendency of cultural polarization for political ambition is yet to proliferate, the hills are alive till date with echoes of this sentiment as evident in the many fond anecdotal associations that are attributed to sites along the road. The settlements are rich repositories of Mughal oral history, reporting as many tales of miracle as regular life events of royal births, deaths, weddings, battles and funerals. While the information that these histories provide may not always be accurate (as in the case of Chadoora, which some locals believe to be the birth place of Nur Jahan, while others are of the opinion that this concept actually exists because Nur Jahan was married to Jahangir from the home of Malik Hyder, whom she respected like a father; the pride is authentic).

Situated in a remotely accessible, landlocked valley that is covered in snow for a quarter of the year, Kashmir had long been compromised by the reaches of civilization. While the rest of India had been developing not only in terms of secure living through progressive agriculture, healthcare and trade, but also high thinking with advancements in art, architecture, literature, music and crafts, inadequacy remained in remote Kashmir in terms of opportunities and resources, both financial and intellectual. With periods of stability being sparsely distributed, for the larger part, the history of Kashmir was marked by rapid shift of reigns, few of which brought relief to a population for whom the changing dynasties often meant little more than an obligatory change of faith to avoid persecution. Rulers as versatile and prolific as Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin were few and far between, and unmatched in terms of their scales of influence with the Mughals. Thus, while pre-Mughal Kashmir is now glorified for its state of independence, the cost that this independence came at for the common people, with poor quality of life and lack of livelihood opportunities, cannot be ignored.

It was effectively the Mughal Road that encouraged a change in this way of life. Under the Mughal rule, it brought to Kashmir peace and prosperity, opened the valley to a possibility of exchange and expansion in trade and culture, and celebrated it on the world map for its generous endowments of natural and cultural heritage on which the state’s thriving tourism industry still relies. Even if the contributions of Mughals were to be quantified, as a people who have brought down the GDP of their land to 3.65 per cent from the highest of 25 per cent during the Mughal era, it leaves one with little right to belittle their legacy. After 500 years of reaping their benefits, if Mughal heritage cannot be adopted as one’s own, then it is a tragedy. Lack of ownership of Mughal heritage is a matter of national shame already, with cultural heritage assets such as the Taj Mahal itself, with a daily footfall of up to 60,000 national and international tourists, being pointedly ignored by the government as Mughal heritage is deemed colonial and, hence, second in priority.

It is important to delegitimize this notion of Mughals being colonizers, as even though Babur came to India as a foreign invader, the generations that followed made it their home. They did not govern India to the advantage a distant native soil, but subsumed their identity with India politically, culturally, economically and genetically, to an extent where when the time came to counter actual colonizers—the British—in the Mutiny of 1857, it was under the banner of Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar that India chose to integrate and fight.

Thus, in spite of any political will to polarize cultures, the idea of India itself remains multicultural and needs to be understood as such. In this light, the Mughal Road needs to be re-established not as an emblem of oppression but as the road that gave the world its first glimpse of Kashmir.

The 'idea' that is the Mughal Road

The decline of the Mughal Road started soon after the reign of Aurungzeb, as the next set of rulers—the Afghans—used an alternate road—the Northern Route—via Uri and Baramulla following the Jhelum basin that was more accessible from their capital at Peshawar. In these 70 years that the Mughal Road lay unused, the mountainous and landslide-prone terrain ensured that it was no longer fit to be used by the time the Sikhs came to power, leading them to continue using the Northern Route, which later came to be known as the Jhelum Valley Road during the Dogra regime. The Banihal Road, through an otherwise inaccessible region in comparison with the Jhelum Valley Road, was constructed during the Dogra period and gained prominence as the shortest connector of Srinagar with the Dogra winter capital of Jammu, further overshadowing the Mughal Road.

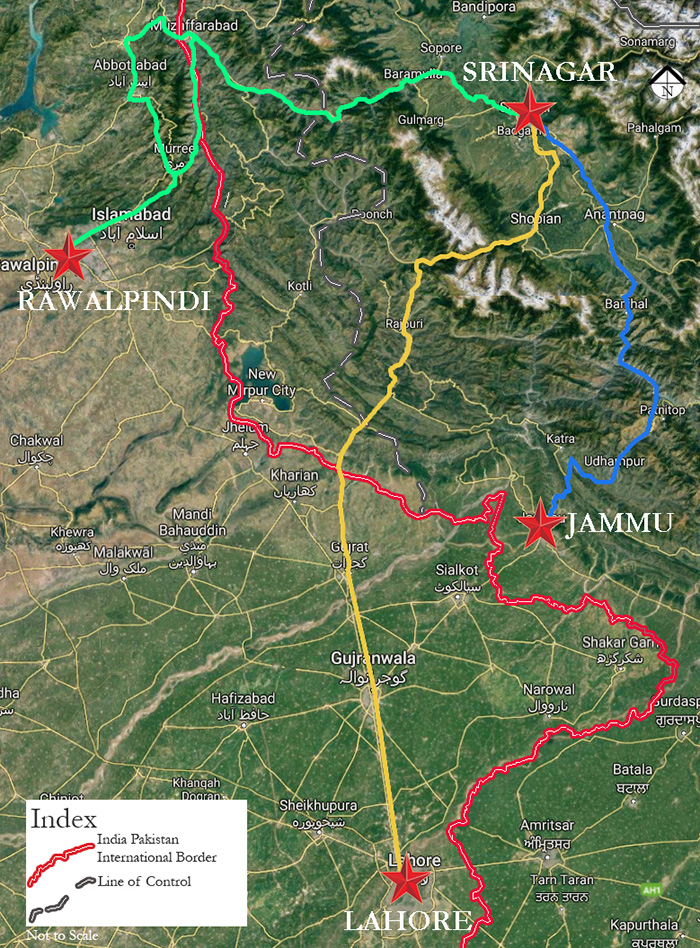

Fig. 1: Key routes of Kashmir – Mughal Imperial Road (yellow), Banihal Road (blue) and Northern Route/Jhelum Valley Road; Source: Authors

Thus, in the 300 years that followed Aurungzeb’s death, the Mughal Road ceased to exist in public memory, remaining alive only to Gujjar and Bakkarwal herders, who continued to use it for their biannual migration from the hills of Kashmir to the plains of Jammu, following the same route and sometimes taking nightly shelter on the same sarais that once housed royalty. In fact, when the reconstruction of the Mughal Road started in 2005, the path it would trace was determined through extensive consultation with the Gujjars and Bakkarwals. However, the road currently promoted by the PWD as the Mughal Road is only a short segment of the entire stretch of the Mughal Road of the Indian section, that too not entirely historically accurate. While engineering concerns were responsible for some deviations, conflict and politics also shaped the current road to a large extent.

Fig. 2: Bakkarwal migration at Peer ki Gali, Mughal Road; Source: Authors

While the idea to re-establish the Mughal Road and reduce the distance between Poonch and Rajouri with Kashmir from 400 kilometres to 170 kilometres had been conceived by Chief Minister Sheikh Abdullah in 1979, one of the unspoken reasons owing to which it was delayed by more than 40 years is because of security concerns regarding the ramifications of allowing a direct physical connection between Kashmir Valley with the Muslim-dominated areas of Jammu such as Poonch and Rajouri. While the imperative to restrict the volatile atmosphere of insurgency in Kashmir strictly within the Valley is known to be the real underlying reason, the vacillation regarding the development of the route is publicly more often attributed to the fact that the Mughal Road is within the firing range of the Pakistani Army—a claim dubitable on accounts of both Pakistan’s policy of appeasing Kashmiri civilians, whom the Mughal Road services, and the improbably long range of the road from Pakistan with the exception of Krishna Gathi. Interestingly, now that the road is open for movement, locals in the Jammu division are of the opinion that it is being used to facilitate a deliberate and calculated migration of Muslim populations from Kashmir to Jammu in an attempt to alter its Hindu majority demography in a bid to consolidate Jammu within the area ideologically ordained by separatists to someday form an independent Kashmir.

Fig. 3: The Mughal Road passes through the Forest Division of Poonch; Source: Authors

The impact of the conflict has also adversely affected the tangible remains associated with the Mughal Road. Of the built assets that can still be traced along the historic route, a majority are in advanced stages of dilapidation—lacking in identification, protection or conservation—born of neglect, which is often attributed by authorities to more urgent priorities of encountering security threats. While the physical fabric of many of the sarais such as Heerpur, Thanamandi, Narian and Chingus have been fully or partially demolished and/or altered, to accommodate security forces in times of military emergencies, locals also hold the lack of management plans responsible for the road not having been included in the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List as part of the sites along the Uttarapath, Badshahi Sadak, Sadak-e-Azam and Grand Trunk Road.

Cultural routes: Lost and found

In no other place in India has conflict shaped the built environment as extensively as it has in Kashmir. From a land situated at the crossroads of the world’s most culturally influential corridors, epitomized by syncretic living, high thinking and creative vibrancy, with linkages between its past and present broken, Kashmir is now the most heavily militarized region of the world and among the most disputed. ‘Conflict is endemic to heritage,’ as David Lowenthal states, where, ‘victors and victims proclaim disparate and divisive versions of common pasts' (Lowenthal 1998:234–35). And it is this very fate of politicizing history that now needs to be avoided by ensuring that threads of research objectively document and analyze the impact of modern conflict on heritage by recording both the archival and current, because the longer the delay the more space there is for manipulation of evidences recording the past. Unbiased studies are required to document the present and recent past through heritage before it can be destroyed as evidence, misinterpreted to strengthen nationalist, religious or ethnic agendas, or re-contextualized to reconstruct history even at the cost of obliterating identities and transforming a culture of peace into a culture of conflict.

Fig. 4: Ancient Sarais function currently as security outposts along the Mughal Road; Source: Authors

Navigating this environment of conflict, mistrust and Emergency in the Valley, only recently have those studies been initiated that aim to understand, manage and reconcile the relationship of aspects such as conflict, heritage, dark histories, identity, politics, socio-cultural trauma, ethical recording and use of memories, institutional frameworks for protection of heritage, terrorscape management, implications of decisions made during or after conflict; and methods by which post-conflict reconstruction and interpretation can be ensured to be neutral. While each of these aspects requires inspection at great depths, they also need to be understood in entirety as each of these individual elements influence the idea of the Mughal Road—a prospect as interesting as it is challenging.

Fig. 5: High military surveillance on the Mughal Road near the Indo-Pak Border; Source: Authors

But then there are many such challenges along the multiple routes in Kashmir that are yet to capture public attention. This is particularly true of the roads leading out of India into hostile hinterlands of Gilgit-Balistan.

One of these is the Turtuk‒Khapulu Road, which was split into two by the Line of Control in 1971 when the Indian Army captured the territory up to the village of Thang in Nubra. Earlier, on that particular day of capture, Mohammad Ali (then 5 years old) had been left behind at home, in the charge of his grandfather. His grandmother and both parents had journeyed on a domestic purpose to the neighbouring village of Franu, which from that day on till date is with Pakistan. As Mohammad’s grandmother and parents attempted to return to their home, entry was barred and a grave Indian Army told them to turn away at gunpoint. No amount of reasoning, pleading or crying would help, as within a few short hours, their homeland had been transformed into a foreign and hostile territory. Even as the physical distance separating Franu and Thang remained 1 kilometre, politically they were farther than this estranged family could ever hope to travel. For over 40 years, the family could not reconnect. More than 40 years were spent in futile hopes, that following the example of Teetwal, some meeting points on the LoC would be thrown open on humanitarian grounds to allow the many estranged families to meet each other again, however briefly.

Growing up practically as an orphan, Mohammad would often go as close to the border as he could—to a point from where he could glimpse the village of Franu at a distance—straining his eyes to see if one of the silhouetted human shapes were his parents, and whether they would respond to his whistling, drum-beating or flag-waving. With a burning and unfulfilled need to convey to the other half of the family that one side was well and missed the other, each day was tormented, knowing that the fragmented family was barely a kilometre away from each other and yet too far out of reach. Eventually, Mohammad’s grandparents perished on either side of the LoC, broken hearted, before they could see each other again. Finally, it was as recently as 2014 that Mohammad was issued a visa to Pakistan. Travelling through Leh, Delhi, Wagah, Lahore, Islamabad (where he had to wait several months for permission to access Skardu as a town under federally administered Gilgit-Baltistan region), Mohammad, in his late forties, finally met his family again. It had taken him 43 years and a detour of nearly 3,000 kilometres of travel to cover the 1 kilometre of mountain track that lay between the family fragments in Thang and Franu.

In comparison, the Mughal Road stretches across 500 kilometres, divided almost equally between India and Pakistan. And our attempt to reconcile this journey has only just begun.

Fig. 6: Children hiking up a road at Turtuk Valley; Source: Vrinda Jariwala

References

Lowenthal, David. 1998. The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History. Cambridge University Press.