Background

The Mughal era left in its wake not only a legacy of military prowess, administrative dexterity, social-cultural plurality, and economic escalation, but also the lasting idea of India as an empire. While the network of routes necessitated by conquests, administrative surveillance, and economic corridors reinforced this idea, the microcosm of kos-minars (tower structures marking distance on the Mughal imperial highways, usually at intervals of one kos, approximated to 4.17 kilometres), bridges, baolis (underground step wells, common in northern and western India), sarais (caravanserais, a civic infrastructure conceptualised in the Islamic world as a roadside inn for travellers across all religions and purposes to rest at the end of a day’s journey), mosques, hamams (bath-houses in the Islamic world, modelled on Roman baths and containing a number of rooms, each being dedicated to a different stage of bathing), and ancillary structures addressing daily needs of travellers at the end of each day’s journey scaled down this enormity into attainable sections of an intimidating whole.

Fig. 1: A Gujjar shepherd leads his flock down the Mughal Road and across the Peer ki Gali Mountain Pass through a snow-storm; Source: Author

‘(E)v’ry Valley shall be exalted, every mountain an hill made low, the crooked straight and the rough places plain’ (Isaiah 40:4) is the particular sentiment that Jos Gommans draws as a befitting parallel to Abul Fazl’s evident pride at the Mughal system of subcontinental communication developed during the reign of Akbar as reflected in the Ain-i-Akbari (Gossmans 2002:106). It was during this period of rapid road-building activity by Akbar that Kashmir was annexed by the Mughal Empire in 1586 CE, and of the four roads (Namak Road, Pakhli Road, Poonch Route and Kishtwar Route) that connected Kashmir to India of the total of twenty-six total roads noted by Abul Fazl linking Kashmir the rest of the world, the Namak Road connecting Kashmir to Lahore went on to receive maximum royal attention for infrastructural reinforcement, leading it to emerge as the most prominent of the few contemporary roads connecting the otherwise isolated, landlocked valley of Kashmir to India, known as the Mughal Imperial Road.

Need for study

Even as Mughals—particularly Akbar, Jahangir, Nur Jahan and Shah Jahan—lavished their love on Kashmir and consequently on this road as it was the primary access route, its peak period of glory was rather short-lived. After the decline of the Mughal Empire, Kashmir was marked by strife with the reigns changing hands frequently—from the Mughals to the Afghans to the Sikhs to the British to the Dogras and, finally, as fragments to the Indian, Pakistani and Azad Kashmiri governments. With each of these governments hailing essentially from regions outside of the valley, the status of principality for the multiple highways connecting Kashmir to the subcontinent kept altering based on the capital and convenience of the rulers, as ease of connectivity remained key to governance.

Therefore, in the period between 1665, when the last Mughal caravan traversed this road under the command of Aurungzeb, and 2009, when it resurrected under the PWD Mughal Roads Project, the road suffered utmost neglect from state policies that rarely prioritised heritage in times of conflict even when it encompassed some of the region’s most breathtaking landscapes and cultural heritage ensembles. In this interim period of more than 300 years, when the Mughal Imperial Road was threatened with complete erasure from community memory, it was kept alive only by the Gujjar and Bakkarwal herders who maintained the continuity of this road by means of their annual migration from the hills of Kashmir to the plains of Jammu and back, often using the remains of the Mughal travel infrastructure, particularly the caravanserai enclosures, as shelter for themselves and their herds at night.

At present, the historicity and former splendour of this road can only be established through records from the Mughal and early colonial eras, oral histories of contiguous communities, and analysis of cultural heritage assets that outline the route as they stand in varying degrees of decay. While opening of this cultural route and historic landscape in 2009 has resulted in renewed public interest in the Mughal Imperial Road’s heritage, these sources of information remain far from the reaches of the majority. It is this gap of common information and absence of contemporary scholarship related to the Mughal Imperial Road that this research aims to address.

Brief description of the roads connecting the Kashmir Valley to Sub-continental India

The Mughal Imperial Road

In the earliest mentions of this road found in the narrative of Chinese traveller and writer Aokong, who visited Kashmir during 659 CE, and again in Kalhana’s Rajtarangini in 12th century CE, the route that would later become the Mughal Imperial Road is most frequently described as a pedestrian track used for the transportation of salt from west Punjab to Kashmir, leading to its nomenclature as the Namak Road or Salt Route.

Most frequently traversed during the Mughal rule and infrastructurally strengthened thereby to support it, this road navigated the Pir Panjal mountain range through the Rattan Pir Pass and Peer ki Gali, connecting Lahore to Kashmir via the halting stations of Gujarat, Dowlatnagar, Kotla Arab Ali Khan, Bhimber, Saidabad, Nowshera, Chingus, Rajouri, Thanamandi, Behramgala, Poshiana, Aliabad, Hirpur, Shopian and Ramu.

The road fell into disuse upon disintegration of the Mughal Empire following Aurungzeb’s demise in 1707 CE, and its mention can only be found infrequently in the accounts of occasional European travellers from the 18th to the early 20th century as the Mughal Imperial Road. From the mid-20th century onwards the road’s span was further compromised through transection, first by the Radcliffe Line and then by the Line of Control, fragmenting it into three sections—in Pakistan (Gujarat, Dowlatnagar), Azad Kashmir (Kotla Arab Ali Khan, Bhimber, Saidabad) and Jammu and Kashmir of India (Nowshera, Chingus, Rajouri, Thanamandi, Behramgala, Poshiana, Aliabad, Hirpur, Shopia and Ramu)—and rendered inoperative in its former state of continuity owing to chronic Indo-Pak hostilities.

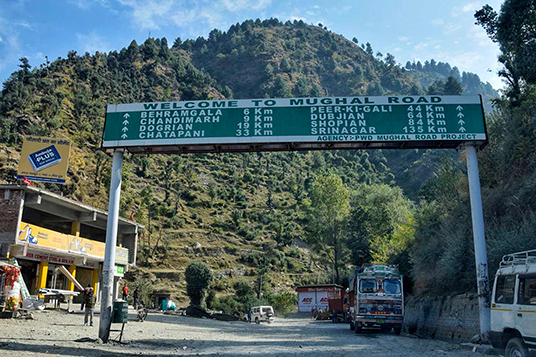

But after centuries of neglect, an idea to revitalise the Indian (Jammu and Kashmir) section of this road was conceptualised in the late 1970s by the then chief minister Sheikh Abdulla to minimise the travel distance between Kashmir and the districts of Poonch and Rajouri, while also making the natural heritage of the Pir Panjal mountains and cultural heritage of the Mughal Imperial Road accessible to visitors. After nearly forty years of delay caused by security, political, engineering, and natural heritage conservation concerns, the road is now once more active as the Mughal Road, even if it is not completely in alignment with its original historic path.

The road usually remains closed from December to March due to heavy snowfall on the Pir Panjal, blocking the mountain passes. Historically, in winter, an alternate road—the Poonch Route—would, therefore, be adopted. However, as travel along the Poonch Route became unfeasible after the LoC was drawn, the traffic was detoured in winter via the Banihal Route.

Fig. 2: Remains of a caravanserai as seen from the recently revived Mughal Road at Aliabad; Source: Author

The Poonch Route and the Jammu Link Road

Effectively a detour on the Mughal Road to bypass the impenetrable snow-clad Peer ki Gali in winter months, the Poonch Route lay further west through the Haji Pir Pass instead, following the same stations as that the Mughal Imperial Road from Lahore (via Gujarat, Dowlatnagar, Kotla Arab Ali Khan, Bhimber, Saidabad, Nowshera, Chingus, Rajouri) till Thana, where it bifurcated towards Suran to reach Uri via Poonch, Kahota, Aliabad, and Hyderabad. From Uri, the Pakhli Route could be followed through Baramulla and Pattan to reach Srinagar. Passing through Azad Kashmir, this route became unusable once the LoC was drawn.

The Poonch Route was often used in conjunction with the Jammu Link Road that connected Jammu to the Mughal Imperial Road at Rajouri via Akhnur, Chauki Chir, Thandapani, Dharamsala, and Sialsia. While this road still exists, it is used more for inter-district traffic rather than as a link between Jammu and Kashmir, as the latter is afforded faster passage using the Banihal Route.

The Pakhli Route

Connecting Kashmir to Pakhli (in present-day Hazara region of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan), this route was used to enter the Kashmir Valley around the year, beginning terrestrially through the ravine of Baramulla, beyond which the remaining journey was undertaken through the waterways of Jhelum and the Wular, interspersed by picturesque halts such as those at Sumbal.

It was this route that was used by Akbar’s army of 5,000 specially equipped horses under the command of Raja Bhagwan Dass and Shah Quli Mehram as they marched from Attock to capture Kashmir in the winter of 1586 CE, startling Yusuf Shah Chak’s army (Mehta 2009:255) as it rested, least expecting invasion during the months when most routes to the valley remained closed. While remains of the Mughal garden of Wah Bagh and imperial camping ground can still be seen at Hasan Abul, where the Pakhli Road begins its ascent from the plains of western Punjab, this road experienced comparatively lesser use from 1586 to 1700 CE, when the Mughal entourage preferred the alternate, shorter route via Namak Road. After years of inactivity, the road was revived only by Afghans, whose journeys were best suited to this road as it connected Kashmir to Kabul and Peshawar on the west.

However, at the end of the Afghan rule and onset of the Sikh period, the road gained notoriety regarding brigands levying arbitrary taxes on travellers. So much so that when William Moorcroft, explorer and employee of the East India Company, set out from Srinagar in the early 1820s via this route, he was given an escort of thirty soldiers, which, in turn, led a great many travellers on the same route to attach themselves to his caravan for protection, creating a formidably large entourage. But even this could not prevent them from harassment at Muzaffarabad, where his passage was blocked by local tribesmen demanding a payment of 15,000 rupees and threatening violence otherwise. Adamant to not pay more than 500 rupees, Moorcroft was forced to return to Srinagar and finally take the Mughal Imperial Road out of the valley (Keenan 2006:103).

In the later Sikh, Dogra, and British periods, the road regained importance as the Murree Route used by the travellers accessing it from Rawalpindi via Murree. From Murree, there were three alternate routes to reach Kashmir:

- via Abbottabad, Mansehra, Muzaffarabad, and Domel, where the road connected to the Jhelum for a clear passage east to Srinagar via Garhi, Uri, Baramulla, and Pattan

- via Kohala, where the Jhelum could be accessed and navigated upstream along the same route from Domel

- via the Kohala–Garhi shortcut

Fig. 3: Current day view of the Pakhli Road near Mohra Power Plant; Source: Author

A macadamized road was constructed along this route and opened to vehicular movement in 1880‒90 as the Jhelum Valley Cart Road, enabling travellers for the first time in history to enter Kashmir in wheeled vehicles. However, the unskilled and reckless drivers made for a journey so unpleasant that it left most travellers not only uncomfortable but also frightened for their lives. Botany enthusiast Miss Marion Doughty, who made this journey in a tonga in 1902, sums up the majority sentiment as she wrote, ‘I have been run away with, I have hunted on wheels in Ireland, and I have raced in a two-wheeled cart for a wager, but nothing had prepared me for that wild thirty mile burst to Baramulla. I have not ridden a mad bull through space, nor been dropped from the moon in a barrel with iron coigns, but I imagine a combination of the two would approximate our pace and progress’ (Doughty 1901:106). So uncontrollable were the horses, so cruel the drivers, and so upsetting the overall scenario that it was not long before two inspection posts were set up on the road by the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Keenan 2006:164).

While conditions of the road improved over the next half of the century, with the LoC being drawn between Chakothi and Uri, the road was divided and limited in terms of usage only intra-nationally by India and Pakistan. It was reopened in 2005 as the Uri-Muzaffarabad Road as part of confidence building measures following Indo-Pak ceasefire in 2003.

The Banihal Route

Historically, the Kishtwar Route—a lesser known pony track through particularly inhospitable terrains—connected Kashmir to Jammu via Kishtwar, Bhaderwah and Ramban. This was the road that the Banihal partially followed and overlapped, linking Jammu to Kashmir via the Banihal Pass on the Pir Panjal range, using Verinag as one of the many picturesque halting stations en route.

As the western territories traversed by the Mughal Imperial Road and the Pakhli Route became a battleground between the Sikhs and Afghans after Emperor Aurungzeb’s death, rendering them too perilous to be used by the common traveller, the comparatively recent route of Banihal gained popularity as it afforded them a reassuring barrier of mountains between the sparring armies, even though it was farther east and by far more circuitous. But this popularity was short-lived as the smaller mountain kingdoms it traversed were also affected by internal strife, making it as dangerous a road as those in the west. It was further challenged economically as travellers were repeatedly and randomly taxed by multiple state tollhouses on the way.

With this road rapidly falling out of favour, few accounts are available of this road till the late 17th century when it was revitalised under the Dogra regime as the shortest route connecting their summer capital at Srinagar to the winter capital of Jammu. Even as the mountainous terrain of Kashmir was difficult to navigate through inclement winters, and the rice fields on the plains of Jammu were unsuitable for passage in monsoon, the road was extensively used and celebrated for the striking view of the Kashmir Valley that it afforded from the Banihal Pass. ‘How calm, how lovely ... the smiling vale (Hervey de Saint-Denys 1853)’, writes Mrs Hervey, one of the many travellers on this road who romanticised and immortalised it in public memory.

Later, during the Dogra regime, the road was restricted till the early 20th century for the exclusive use by the royal family. However, in 1915 it was open to public vehicular transport as the Banihal Cart Road. After closure of the Pakhli route post-Partition and until the Mughal Road was revitalised, the Banihal route remained the only connection from mainland India to Kashmir. Currently, with multiple road and rail tunnels having been bored through the mountains, it remains the most popular route to Kashmir from India.

Fig. 4: Key historic routes connecting Kashmir Valley to Sub-continental India; Source: Author

Table 1: Key Routes, Users and Peak Periods of Usage

|

# |

Principal Route |

Alternate Nomenclature |

User |

Peak Usage |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Mughal Imperial Road |

Namak Road (659–1580) |

- |

Mughal (1580–1664)

Government of India (2009‒current) |

|

Mughal Imperial Road (1580–1707) |

Mughal |

|||

|

Mughal Road (2009‒current) |

Government of India |

|||

|

2 |

Pakhli Road |

Pakhli Route (1586–1846) |

Mughal/Afghan |

Afghan (1750–1819)

Sikh (1820–1846)

Dogra/British (1846–1947)

Governments of India and Pakistan (2005‒current) |

|

Murree Road (1846–1890) |

Sikh/Dogra/British |

|||

|

Jhelum Valley Cart Road (1890–1947) |

Dogra/British |

|||

|

Uri‒Muzaffarabad Road (2005‒current) |

Governments of India and Pakistan |

|||

|

3 |

3A. Poonch Route |

Poonch Route (1846–1947) |

Dogra/British |

Dogra/British (1846–1947) |

|

3B. Jammu Link Road |

Jammu Link Road (1846–current) |

Dogra/British/Government of India |

Dogra/British/Government of India (1846–current) |

|

|

4 |

Banihal Route |

Kishtwar Route |

- |

Dogra/British (1915‒47 )

Government of India (1947‒current) |

|

Verinag Route (1600–1750) |

Mughal/pre-Afghan |

|||

|

(1915‒47 ) Banihal Cart Road |

Dogra/British |

|||

|

(1947‒current) NH1A, NH44 |

Government of India |

Heritage of the Mughal Imperial Road

Rise of the Mughal Road/Early Caravans on the Mughal Imperial Road

As mentioned before, the Mughal Imperial Road owes its origin to the erstwhile Namak Road or Salt Route, which was initially used exclusively for the import of salt from the plains of west Punjab to the valley of Kashmir by a path that crossed the Pir Panjal through the Peer ki Gali mountain pass situated centrally on the mountain range. Early references to this road are found in the narrative of Chinese traveller and writer Aokong, who visited Kashmir in the 7th century, Kshemendra’s Samay Matrika written in the 10th century, and Kalhana’s Rajtarangini from the 12th century CE. However, it was not until the 16th century, under the Mughal rule, that this road rose to prominence as the shortest route connecting the Mughal capital of Lahore to their summer retreat that the valley emerged to be. Referred to as the Mughal Road even today after its most magnanimous patrons, under them the erstwhile Namak Road was realigned, frequented by royal and noble entourages, infrastructurally strengthened, and glorified in memoirs and treatises to establish it as one of the most favoured accesses to the valley from the sub-continental plains as described in details by Abul Fazl in Ain-i-Akbari, Emperor Jahangir in Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, and Francois Bernier in Travels in the Mogul Empire.

It was in November 1586 that Yusuf Shah Chak was defeated by the army of Emperor Akbar making Kashmir a part of the vast Mughal Empire, but Akbar himself did not visit the valley until June 5, 1589. It was to facilitate this imperial visit that the first road improvement activities were undertaken on this road by Qasim Khan—builder of the Agra Fort, but more importantly the engineer of the Agra Lahore Route who is credited for the levelling of its roads, construction of bridges on the Indus, and rendering the infamous Khyber Pass navigable—who employed 3,000 stone-cutters, mountain miners, and splitters of rocks along with 2,000 diggers to transform a narrow pedestrian road into a highway fit for an emperor and his marching armies that included both elephantry and cavalry (Gommans 2002:106). Even then, the mountainous road could only be covered over a long span of six weeks from Lahore to Kashmir.

The Mughal love affair with the verdure of Kashmir, an idyllic life in the Himalayas that thus began with Emperor Akbar, continued till the late 17th century. But even as emperor after emperor made their way into Kashmir, each leaving indelible impressions in the culture of this land, none were more dedicated than Emperor Jahangir either to the valley or to the road leading to it.

While Jahangir had accompanied Akbar to Kashmir several times in his youth, typically during fall, it was after his coronation and towards the latter half of his reign that travelling to Kashmir, usually with Nur Jahan in spring, became a matter of annual court tradition. In 1620, 1622, 1624, 1625, 1626, and 1627, Jahangir kept returning to Kashmir, leaving Lahore in March or April in order to reach Kashmir by May, each time travelling deeper into the valley (Findly 1993:253). Even as parallel activities such as documenting the highland biodiversity with court painters and planning elaborate pleasure gardens accentuating the beauty of the valley were undertaken by the emperor, the central idea of basking in the bounties of nature that Jahangir initiated in Kashmir established a precedence that still renders the Kashmir as a romanticized getaway.

However, the transit to Kashmir and the preparations enabling it was far more expensive and tedious in the past and so time consuming that in the later years of Jahangir’s reign it is said, ‘the court was either in Kashmir, in transit to or from Kashmir, or packing or unpacking from the trip’ (Findly 1993:253). The Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, however, records the annual journey as a joyous event, practically a celebration for the people of Kashmir, who escorted the royal cortege, lined the road as the retinues passed, beat drums, and shouted praises for the Mughal emperor. However, a contrasting view is presented by Palsaert who noted that with the mountain roads not always being suited for pack animals, much of the burden had to be carried by labourers, for whom the emperor’s pleasure trip was cause for much suffering, inducing the author to critically note that ‘the king prefers his own comfort or pleasure to the welfare of his people’ (Findly 1993:253).

Whatever may have been Jahangir’s intention, to ease his own journey or that of his labour force, having first transformed the valley as a retreat that he frequently travelled to, he soon turned to the next logical task of making this long journey less arduous. In 1620, following the emperor’s orders ‘that from Kashmir to the end of the hilly country buildings should be erected at each stage for the accommodation of myself and the ladies, for in the cold weather one should not be in tents’ (Jahangir 1978), the construction of a chain of small stations along the road was initiated to shelter royal travellers on this road (Koch 2014:90). In addition to these buildings (caravanserais), contemporary travellers’ accounts and recent archaeological finds also indicate the existence of mosques, watch towers, gateways, retaining walls, bridges and aqueducts as manifestations of Mughal travel architecture on this road. Local settlements also grew around these stations using these nodes of activity as a focal point, adding to the dynamics of the route.

Having extensively refurbished the road for better travel experience, perhaps it is only natural that Jahangir made his final journey and breathed his last also on this road in 1627. While the exact location of his death is disputed between Aliabad, Behramgala, Thanamandi and other stations in the upper reaches of the road, the sarai most closely associated with his death is at Chingus. According to widespread oral tradition, the name of the sarai is derived from the Farsi translation of the word intestine—chingus—as the tomb within the sarai courtyard and next to the mosque is believed to contain Emperor Jahangir’s entrails, buried there in accordance with Empress Noor Jahan’s orders in an attempt to hide the emperor’s unexpected death. It is believed that after the intestines were buried to prevent decay of the corpse, Jahangir’s embalmed body was propped on his elephant for the rest of the way to Lahore to prevent potential successors from hearing of or believing the news of the emperor’s demise, until the royal entourage reached the more solid political grounds of Lahore, where the death could be formally announced and the inevitable ensuing politics for the throne better managed.

Fig. 5: Remains of the Sarai Chingus; Source: Author

While Jahangir’s love for Kashmir was enough for him to negate the tedium and upheaval of moving the court on the long journey to Srinagar, and his physiological need to escape to cooler climates for release from his opium and alcohol induced physical unease in the warm plains of India ensured that he went to the valley multiple times, putting the Mughal Imperial Road to consistent use, the same enthusiasm was missing in both Shah Jahan and Aurungzeb.

While it is known that Shaj Jahan, his daughter Jahanara, and son Dara Shikoh made multiple journeys to Kashmir, few records of the Mughal Imperial Road are available from this time period. However, significant construction (Bamzai 2008:399) and refurbishment work of caravanserais en route are believed to have been undertaken by Ali Mardan Khan—governor of Kashmir as appointed by Emperor Shah Jahan in 1638—to an extent where in many cases the attribution of benefaction is no longer of certainty between key probable patrons—Jahangir and Ali Mardan Khan. An example of such a case is the caravanserai at Aliabad, which although widely ascribed and said to owe its nomenclature to Ali Mardan Khan, also finds mention in the accounts of Jahangir some twenty years earlier. What is more likely, however, is that while the fifteen primary halting stations (refer to Table 2) were constructed under the patronage of Jahangir, the second set of intermediate stations (refer to Table 3) enabling an even easier passage were erected by Ali Mardan Khan.

The final record of a Mughal emperor achieving this stupendous feat of travel comes from Francois Bernier’s letters as he accompanied Emperor Aurungzeb to Kashmir in December, 1664. This journey, Bernier insists, was only undertaken owing to the persuasive prowess of Aurungzeb’s favourite sister and first lady of the contemporary Mughal court, Roshanara, who longed to use the journey as a means to appear in regal splendour outside the confines of harem life, as Jahanara had before her on the same journey with their father Shah Jahan.

While there is no denying that her ambitions were fully met by the grandiose entourage, it also came at the cost of logistic alarm. Manucci, who accompanied the emperor for the initial three days of the journey, records that 300 camels were required only to carry a small portion of the royal treasures en route with ‘two hundred camels, loaded with silver rupees, and each camel carrying four hundred and eighty pounds’ weight of silver; one hundred camels loaded with gold coin’ (Manucci 1907‒8: 60‒9). No wonder then that in its entirety, the royal caravan replete with royalty, nobility, army, traders, their families, servants, porters, thousands of horses, elephants, camels, oxen, cattle, goats and other animals was in effect an entire city on the move, making for a journey that was as chaotic as it was slow. With a 6‒7 miles circumference, and laid out in a predetermined formation with the royal pavilion at the centre circumscribed by successive circle of tents according to the ranks of their owners, camp life was comparatively smoother under the orchestrations of the grand quarter master and his engineers who travelled ahead of the procession with a duplicate set of royal encampment materials to have the site ready to welcome the emperor before his arrival. But with Aurungzeb’s frequent pauses for hunts decreasing the pace of travel, the road from Delhi to Lahore that was normally covered in fifteen days was stretched longer over two months. And even further delay lay ahead in Lahore as the caravan awaited the snows covering the passes of Pir Panjal to melt, pushing them to the April heat of western Punjab’s plains. When they finally renewed their travels for Kashmir from Lahore, each of Bernier’s letters written on the first fortnight of journey from Lahore to Bhimber are marked by despair and doubt as he writes of his conditions as well as that of his horse and his Indian servant:

I declare, without the least exaggeration, that I have been reduced by the intenseness of the heat to the last extremity; scarcely believing when I rose in the morning that I should outlive the day. This extraordinary heat is occasioned by the high mountains of Kachemire; for being to the north of our road they intercept the cool breezes which would refresh us from the quarter, at the same time that they reflect the scorching sunbeams, and leave the whole country arid and suffocating.… Every day is found more unsupportable than the preceding, and the further we advance the more does the heat increase.… (W)hat can induce and European to expose himself to such terrible heat, and to these harassing and perilous marches? Is it too much curiosity; or rather it is gross folly and inconsiderate rashness? My life is placed in continual jeopardy.… The sun is just but rising, get the heat is in supportable. There is not a cloud to be seen nor a breath of air to be felt. My horses are exhausted; we have not seen a blade of green grass since we quitted Lahor. My Indian servants, notwithstanding there black, dry, and hard skin, are incapable of further exertion.... (T)he ink dry ice at the end of my pen, and the pen itself drops from my hand. (Bernier 1916:385‒8)

Happily for the caravan, the climate grew cooler at Bhimber from where the five days of marching to Kashmir began. The limited provisions resulted in the entourage to be divided into two at this juncture—a fortunate few who were allowed after strict identification by officers stationed at the pass to travel with the emperor on to Kashmir, and the less privileged ones who were to remain behind at Bhimber waiting for the Emperor’s return till the end of warm weather, even as they pined for the cooler climates of Kashmir. The animals too were carefully chosen at this point, with the camels unsuited for the rocky climb being discarded for the remaining journey, and there burdens transferred to porters instead. Those selected to travel onwards to Kashmir included the women of the seraglio, the vizier, the high steward, the masters of hunts, and rajas, omrahs (a Mughal high official of rank lower than 12,000 but above 1,000), and mansabdars (a Mughal high official of rank lower than 1,000 but above 20) of the uppermost echelon besides, for whom the departure was further staggered into groups departing on successive days with the aim to decrease the crowding and confusion in the picturesque but perilous mountainous roads ahead. Even then, accidents could not be wholly averted. In a collision and ensuing panic that took place among the elephants carrying the ladies of the harem up the narrow path, three or four women were killed and fifteen elephants lost their footing and fell down the cliff. Even as Bernier passed by the site of this accident two days later, he noted that even though some elephants were still alive and waving their trunks, with no way to lift and save them, they had to be left behind to die. In an early edition of Bernier’s travels that was published in Amsterdam in 1672, the Pir Panjal Pass is marked by a pitiful picture of dead elephants (Keenan 2006:82).

Vividly as it is depicted by Bernier, this was the last great passage along the Mughal Imperial Road, as with the death of Aurungzeb and the disintegration of the Mughal Empire, the territory that this route traversed was torn by strife between the Sikhs and Afghans. While the road remained open for local short-distance travellers, the Pakhli route, the Banihal route, and the Jammu Link route with Poonch route became significantly more popular. Most of these routes too fell into disuse or limited use as they were fragmented and rendered unusable first by the Indo-Pak national border and then again by the Line of Control. With Banihal being the only road connecting mainland India to Kashmir 1947 onwards, the Mughal Road was revived as a second road as recently as in 2009, albeit in a slightly altered form from the historically accurate alignment and limited in function within the Indian border in Jammu and Kashmir. Even as it remains closed under a heavy blanket of snow for a quarter of the year, the road has become popular to visitors since and opened up to the public eye both the natural beauty of the Pir Panjal range as well as the cultural heritage assets that remain as reminders of the glorious culture of Mughal travel along this route in the old halting stations.

Natural heritage of the Mughal Imperial Road

The Mughal Imperial Road is not only a connector of cultures but also links geographic regions that are dramatically different from each other. From the hot plains of western Punjab, through the agricultural field and low hills of Jammu, past the challenging passes and rugged mountains of the Pir Panjal, and finally into the lush valleys and orchards of Kashmir, the swiftly changing landscape is as much an asset to the road as the Mughal cultural heritage assets that stand along its course.

Fig. 6: View of the lower hills of Jammu from the contemporary Mughal Road; Source: Author

The first variation in the landscape is found at Bhimber, where the road leaves the flatlands and begins its ascent on to the low hills of Shivaliks that range from 1,000 to 3,000 metres above mean sea level. From Saidabad to Nowshera, the path descends on to the broad valley of the Nowshera Tawi, which determines the landscape till the villages of Baffliaz by the Poonch River. As Jahangir keenly observes of this plain segment in his memoirs, the similarities between this land and Kashmir are mere acquired characteristics while in actuality the area is warm country, as reflected in climate, clothing, and animals. He also notes of Rajouri, which comes under this stretch, as home to hills skirted in violets and a superior quality of the rice grain than that produced in Kashmir. He further records that a river at Rajauri—either the Tawi or the Sukh Tao—gets poisoned in the rainy season causing symptoms of swellings in the throat, yellowness, and weakness among the residents (Jahangir 1978). The road beyond Rajauri crosses the Rattan Pir Pass situated at an elevation of 2,500 metres before Behramgala, where the zigzagging road of the plains ends at the foot of the Pir Panjal and is marked by the presence of a waterfall named Noori Chamb after Empress Nur Jahan, who, according to oral traditions, is believed to have enjoyed bathing and relaxing under its cool sprays during the summer months. The waterfall is estimated to be at an elevation of 3,480 metres with its main sources of water being the high altitude alpine lakes of Lucksar and Kolsar situated a further 400 metres above the waterfall.

Fig. 7: Landscape of the Pir Panjals as seen at Peer ki Gali; Source: Author

In this second shift from tropical to temperate that begins at Behramgala, the landscape begins to change with ascent from the deciduous forests of the plains, to pines and firs, ultimately giving way to alpine meadows near the Peer ki Gali mountain pass at a height of 3,490 metres. The span here, between the consecutive stations of Poshiana and Aliabad Sarai, experience heavy snows from late October to February, blocking the pass and rendering the road dangerous and unusable.

In the third shift, the road descends again from Aliabad, across the lush meadows of Dubjan and follows the valley of Rambiar River into the Valley of Kashmir through Hirpur. While it was not located in this study, a waterfall is known to have existed in the neighbourhood of Hirpur of which Emperor Jahangir exclaims in his memoirs, ‘What can be written in its praise? The water falls down in three or four gradations. I have never seen such a beautiful waterfall. Without hesitation, it is a site to be seen, very strange and wonderful.’ (Jahangir 1978) Further, Hirpur is also home to the endangered Markhor goat (Capra falconeri), which is protected by the Hirpur Wildlife Sanctuary intersected by the road. Beyond Hirpur and until Srinagar, the road traverses a gently undulating landscape. The coniferous forests are replaced by poplars and chinars, which thin out on the settlement edges to accommodate apple orchards and paddy fields.

Fig. 8: The Valley of Kashmir as seen from the Aharbal Junction; Source: Author

Cultural heritage of the Mughal Imperial Road

The journey through the Mughal Imperial Road typically began for the Mughal emperors from the city of Lahore. The march across the scorching plains from Lahore to the slightly elevated grounds of Bhimber via Gujarat was covered in a fortnight (Bernier 1916:358). The journey from Bhimber to Srinagar ascended and descended to cross the Pir Panjal range at various passes, which have been recorded in travel accounts as the Rattan Pir Pass and the Peer ki Gali. This second portion of the journey was covered over a period of five to seven days, but as the entourage had to traverse narrow and potentially dangerous mountainous roads, the travel party was staggered in their departure from Bhimber. The roughly 246 miles/396 kilometres of road between Lahore and Srinagar was divided by 15 primary halting stations into 16 marches, whose distances as provided in Charles Ellison Bates’s Kashmir gazetteer are tabulated below. On an average, the intermediate distance between successive halting stations is 11.73 miles/18.87 kilometres, the value of which though, in reality, deflected towards a higher side to 18 miles/28.96 kilometres in the plains and a lower denomination of 8 miles/12.87 kilometres for more difficult climbs.

Table 2: Halting stations and Estimated Intermediate Distances on the Mughal Imperial Road (Bates 2005:430‒35)

|

# |

Halting Stations |

Estimated Distance (in Miles) |

Estimated Distance (in Kilometres) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Origin/ Destination |

Lahore |

|

|

|

1 |

Gujarat |

70 |

112.60 |

|

2 |

Dowlatnagar |

12 |

19.31 |

|

3 |

Kotla Arab Ali Khan |

8 |

12.8 |

|

4 |

Bhimber |

8.5 |

13.6 |

|

5 |

Saidabad |

15 |

24.14 |

|

6 |

Nowshera |

12.5 |

20.11 |

|

7 |

Chingus |

13.5 |

21.72 |

|

8 |

Rajouri |

14 |

22.50 |

|

9 |

Thanamandi |

14 |

22.50 |

|

10 |

Behramgala |

10.5 |

16.89 |

|

11 |

Poshiana |

8 |

12.8 |

|

12 |

Aliabad Sarai |

11 |

17.70 |

|

13 |

Hirpur |

12 |

19.31 |

|

14 |

Shopian |

8 |

12.8 |

|

15 |

Ramu |

11 |

17.70 |

|

Origin/ Destination |

Srinagar |

18 |

28.96 |

At present, taking into consideration the fragmentation of the road caused by the Indo-Pak national border and the Line of Control, the section of the road that remains with India, and has been covered by this study, encompasses 120 miles/193 kilometres from Nowshera to Srinagar.

The following sites were identified as a combined list of natural and cultural heritage assets, halting stations and intermediate sites, sites recorded in history and sites identified by remains of Mughal caravanserais existing therein and located with the help of contiguous communities. Details of each site as found through either ground survey or secondary research, or both, are provided below.

Table 3: Key Sites Defining the Mughal Imperial Road from Nowshera to Srinagar

|

# |

Key Sites |

Location |

Distance between sites according to the current road system (in kilometres) |

|

|

Halting Stations |

Intermediate Sites |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

Nowshera |

|

District Rajouri, Jammu and Kashmir, India |

20 |

|

2 |

|

Narian |

9.1 |

|

|

3 |

Chingus |

|

12 |

|

|

4 |

|

Muradpur |

16.5 |

|

|

5 |

Rajouri |

|

6 |

|

|

6 |

|

Fatehpur |

5.3 |

|

|

7 |

Thanamandi |

|

16.6 |

|

|

8 |

|

Baffliaz |

District Poonch, Jammu and Kashmir, India |

8 |

|

9 |

|

Noori Chamb |

23 |

|

|

10 |

|

Chandimurh |

||

|

11 |

Behramgala |

|

2.1 |

|

|

12 |

Poshiana |

|

20.7 |

|

|

13 |

|

Peer ki Gali Mountain Pass |

|

12 |

|

14 |

Aliabad Sarai |

|

District Shopian, Jammu and Kashmir, India |

7 |

|

15 |

|

Lal Gulam |

|

|

|

16 |

|

Sukh Sarai |

|

|

|

17 |

|

Dubjan |

|

|

|

18 |

Hirpur |

|

39.4 |

|

|

19 |

Shopian |

|

|

|

|

20 |

|

Shadimarg |

District Pulwama, Jammu and Kashmir, India

|

9 |

|

21 |

|

Mitrigam |

8.6 |

|

|

22 |

Ramu |

|

District Budgam, Jammu and Kashmir, India

|

2.3 |

|

23 |

Kanakpura |

|

15.6 |

|

For details on individual sites please refer to the article, 'Sites on the Mughal Imperial Road'.

Decline of the Mughal Road

With the shift of power from the Mughals to the Afghans after the death of Aurungzeb, the Mughal Imperial Road saw a gradual decline as the new rulers favoured the Pakhli Road as it better connected Kashmir to the west with their principal cities of Kabul and Peshawar. The same Pakhli route was also preferred by the Sikhs as it offered better connectivity with Rawalpindi. In the period of power struggle between the Afghans and the Sikhs, which rendered the roads passing through western Punjab dangerous, travellers to Kashmir chose to use the Banihal route that detached them from the marauding armies in the west by a wide berth and a protective shield of high mountains. With the Mughal Imperial Road being used in this period only by local travellers, few written records remain of the road until the early 19th century, when during the comparative stability of the Sikh and Dogra regime, some adventurous European travellers covered this landscape, making copious notes on aspects of natural and cultural heritage of the road that fascinated them. Of these some records have survived to the present day, enabling us to picture the Mughal Imperial Road as it was from 1820s to the 1890s, when with the opening of the Jhelum Valley Cart Road the traffic on the Mughal Imperial Road once again stopped, in favour of this new motorable path. Some of the most important travellers in this period, in terms of the details that they provide of the Mughal Imperial Road, include William Moorcroft, Baron Charles von Hügel, Ms Honoria Lawrence, and Frederic Drew, who travelled down this road in chronological succession in 1823, 1830, 1850, and 1862.

From Moorcroft’s accounts it is evident that in the 1820s, the condition of the Mughal Road had deteriorated so far that it was overshadowed by the access through Baramulla via the Jhelum waterways, even as the latter was notorious for brigands. This was the path that Moorcroft initially selected to travel out of the valley. But even his massive caravan with its armed escort could not go beyond Muzaffarabad as their way was blocked by local tribesmen demanding a sum of money so large in exchange for safe passage that Moorcroft was obliged to retreat to Srinagar and choose what can be assumed was the second most favoured pathway—the Mughal Imperial Road—where he used the dilapidated Mughal sarais as resting places.

In 1830, for Hügel, too, the Mughal Imperial Road was far from being the first choice. At this time, in order of Hügel’s preferences, there appears to have been three different routes to Kashmir—the first over the highest mountains of the Himalayan range through the Berenda Pass, a second across the lower Himalayan ranges by way of Bilaspoor, Mundi, Dankar and Ladakh, and the third across the plains of Punjab that could culminate either in the Kishtwar route or the Mughal Imperial Road (Hügel 2000:16‒18). However, it must be borne in mind that with adventure and travel being key priorities to Hügel, this sequence of preference cannot be assumed to have applied to the general population in uniformity. Travelling through either of these three routes in 1830s required express permission from Maharaja Ranjit Singh. For Hügel, this proved to be an extremely long-drawn-out affair, as the application he had made in May was approved only in October, dashing his hopes of taking either of the first two routes owing to inclement weather and snow blockage on these paths at the time of the year. Instead, he was forced to travel from his station at Shimla by way of Bilaspoor, Jwalamukhi, and Narpoor to reach the Mughal Imperial Road at Rajouri using a short cut on the Jammu Link Road, avoiding the Kishtwar route altogether, as it was deemed to lofty and dangerous, particularly for pack animals.

Even as Hügel was initially disappointed by the Mughal Imperial Road, which he describes as uninteresting, bad, intersected in all directions by hills, lined by paltry settlements and tropical vegetation, beyond Behramgala his mood changes and his journal instead reflects delight at romantic roads, lush forests, lofty mountains, and beautiful waterfalls. From Hügel’s narrative it is evident that most of the Mughal travel infrastructure along the road was by then in advanced stages of decrepitude, as he prefers to camp near them and never actually in them as done by his predecessors, describing them unequivocally as ‘ruins’, be it the sarai at Thanamandi, Behramgala, Poshiana, Inganali Kilah or Kanakpur. The only sarai that appears to still have been inhabitable in 1830 was that at Aliabad, which Hügel states to be better known as the Padshahi Sarai. Capturing both the condition of the sarai, the administration of the road, and hardship of life therein, the Aliabad Sarai, he writes:

(i)s completely hemmed in on every side by high snowy mountains, and is the only abode kept up for the reception of travellers in this part. The desolate tract between Rajouri and Kashmir is so thinly inhabited that, if it were not for the station, which is occupied by a corporal and few sepoys, who are not relieved until they have passed several years in this wilderness, travellers would indeed be sadly off. In October they lay in the winter stock of provisions, wood, &c.; at the end of November the snow storms begin, and from that time the men do not even venture into the yard, where the snow remains piled up for months…. My little tent was pitched in the middle of this yard and the cold was certainly most piercing. (Hügel 2000:90)

In addition to the caravanserai which find mention in a majority of travellers’ accounts, Hügel’s notes are also important to establish the flora along the road, as well as the presence of less talked about structures such as the pleasure gardens and aqueducts at Rajouri, watch towers housing royal troops throughout the year at Peer ki Gali, retaining walls at Lal Gulam, and two mosques at Ramu. Further ahead of Aliabad Sarai, he notes the presence of a fortress and towers of Iganali Kilah of which he writes:

Four kos from the Padshahi Sarai, we arrived at the picturesque fortress of Inganali Kilah; two branches of the Damdam river unite here, and the mountain sinking abruptly to a hill, discloses also two detached towers defending the entrance of the mountains, which towards the north, from the right bank of the stream, might be easily mastered. At all other points it may safely be deemed impregnable. The Sarai now in a ruined state, from the frequent facing masses, which have destroyed the former approaches, lies at the base of the mountains, and near the river. (Hügel 2000:94)

While the locational and physiographic description almost certainly indicates that this fortress is the same as the current Sukh Sarai, the vast difference in description is key to understanding the decay of the building, as well as to establishing the need for archaeological excavations to identify the vanished structures and their foundations. The final contribution of Hügel is in the recording oral histories of the road, of which he describes particularly elaborately the story of a man-eater—Lal Gulam—who, according to legends surrounding Ali Mardan Khan and his force of road engineers and labourers, was a resident of a tower by the road from where he preyed upon its travellers, seizing them and hurling them down the precipice where he devoured them at leisure, until his son was killed by the brave Ali Mardan Khan, bringing an end to Lal Gulam’s reign of fear on the Mughal Imperial Road. While this story is rejected by Hügel as superstition, he does draw the readers’ attention, in relation to this story, to countless skeletons of whitened human, horse and oxen bones by the road, reiterating the dangers of travel along these paths (Hügel 2000:94).

The next report that comes from this road is that of Ms Honoria Lawrence, who travelled along this road on a dhoolie, (a simple litter used for transport and carried usually by four men) regretful of the Mughal days of comfort that was evidently missing in 1850. Of the glorious days that the road had seen during Mughal rule, she writes in a letter to her son:

(N)othing remains, save the halting places built at about every ten miles for the Emperor. These exist still, some in absolute ruins, some partly habitable, all built on the same plan: a large open quadrangle, corridors, serving for stables and such like running along two sides, the side facing the gateway containing the royal apartments. The material is stone with a small proportion of brick. (Keenan 2006:103)

What is interesting, however, is the fact that, according to Lawrence, these sarais were upgraded in 1850 by Maharaja Gulab Singh, the first Dogra king of Jammu and Kashmir, with the equipment of humble apartments in the corner of the old sarai enclosures that were made of earthen floors and walls, and wood planked ceilings. So poor were the conditions of the rest of the sarais that even such basic facilities were deemed by Lawrence as ‘welcome shelters’ in comparison.

The final memoirs from the road come from Frederic Drew in 1862, where he records the sarais of Bhimber, Saidabad, Nowshera, Chingus, Rajouri and Thanamandi, among others. While his descriptions of most of the sarais corroborate with those before him, it appears that between 1830 and 1862, the sarai at Thanamandi underwent the largest transformation, with the ruins and resident Kashmiri families therein mentioned by Hügel having disappeared, leaving only the courtyard behind.

From 1890s the traffic on the Mughal Road decreased even further in favour of the vehicular Jhelum Valley Cart Road. In 1915, the Banihal Cart Road was constructed, and became a key spine connecting Kashmir to the Dogra summer capital of Jammu and further on to mainland India. This second road was further reinforced after 1947, when the Jhelum Valley Cart Road, having been fragmented by the Indo-Pak national Boundary and the Line of Control, was no longer usable. The Mughal Imperial Road, however, remained ignored until 1979.

Revival of the Mughal Imperial Road

While the idea for revitalisation of the Mughal Imperial Road to use it as an alternative connection to Kashmir, decongest the Banihal Route, reduce the distance between Poonch and Rajouri with Kashmir by more than half from the long detour that an inevitable journey through Banihal Route implied, and make accessible the natural and cultural landscape of the Pir Panjal to visitors was conceived by Chief Minister Sheikh Abdullah in 1979, multiple reasons—both articulated and unspoken—resulted in a delay of more than 40 years in transforming this vision into reality.

With the demise of Sheikh Abdullah in 1982, the project was stalled by the paucity of funds and objections raised by the Defence Ministry of India. It was not until 2005 that works could be re-started under the leadership of then Chief Minister Mufti Mohammad Sayeed as part of the Prime Minister’s Reconstruction Programme. With an allocation of 79.50 crores from the Centre and a total estimated cost of 255 crores, work began in full force with two Mughal Road divisions being revived at Surankot in Jammu and at Shopian in Kashmir. With the foundation of this prestigious project having been laid on October 1, 2005, re-construction of the road was started simultaneously from both ends—at Buffliaz and Shopian—in the February, 2006 with a target for completion in 2007.

However, works were mired again in 2007 by serious objections raised by wildlife conservationists resisting the fragmentation of wildlife movement corridors of the Hirpora Sanctuary, with particular concern for the endangered Markhor goat that inhabits the sanctuary. Further opposition came against the claim that this road would be an alternative to the Banihal route, as it was sure to be blocked in the winters by snow. However, conditional permission for the construction of the road was permitted by the Supreme Court and the road was opened for an inspection by a standing committee of the Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Council on July 12, 2009.

Of the implicit reasons for delay, of course, was security concern regarding the ramifications of allowing a direct physical connection between Kashmir Valley with the Muslim-dominated areas of Jammu such as Poonch and Rajouri. While the imperative to restrict the volatile atmosphere of insurgency in Kashmir strictly within the valley is known to be the real underlying reason, the vacillation regarding the development of the route is publicly more often attributed to the fact that the Mughal Road is within the firing range of Pakistani Army—a claim dubitable on accounts of both Pakistan’s policy of appeasing Kashmiri civilians whom the Mughal Road services, and the improbably long range of the road from Pakistan with the exception of Krishna Gathi. Interestingly, now that the road is open for movement, locals in Jammu division are of the opinion that it is being used to facilitate a deliberate and calculated migration of Muslim populations from Kashmir to Jammu in an attempt to alter its Hindu majority demography in a bid to consolidate Jammu within the area ideologically ordained by separatists to someday form an independent Kashmir.

Fig. 9: Entry point to the Mughal Road from the Jammu Section; Source: Author

Impact of conflict has also adversely affected the tangible remains associated with the Mughal Imperial Road. Of the built assets that can still be traced along the historic route, a majority are in advanced stages of dilapidation—lacking in identification, protection, or conservation—born of neglect that if often attributed by authorities as a result of more urgent priorities of encountering security threats. While the physical fabric of many of the sarais such as Heerpur, Thanamandi, Narian, and Chingus have been fully or partially demolished and/or altered, to accommodate security forces in times of military emergencies, locals also hold the lack of management plans responsible for the road not having been included in the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List as part of the sites along the Uttarapath, Badshahi Sadak, Sadak-e-Azam, and the Grand Trunk Road.

Further, the road itself that is currently being promoted by the PWD as the Mughal Road is only a short segment of the entire stretch of the Mughal Road of the Indian section, which is not entirely historically accurate. While extensive consultation with the Gujjars and Bakarwals were held at the onset of the road’s reconstruction activities to determine the historic path, obvious deviations do exist, owing to engineering concerns as well as conflict politics that have shaped its current alignment to a large extent.

Statement of significance

The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes states that:

Cultural Routes reveals the heritage content of a specific phenomenon of human mobility and exchange that developed via communication routes that facilitated their flow and which were used or deliberately served a concrete and peculiar purpose (ICOMOS 2008:2).

Assessed against the five key elements that the Charter defines as qualifiers – content, context, cultural significance, dynamic character, and settings – the Mughal Imperial Road needs to be understood as a Cultural Route.

Values

The road holds a high associational value with the Mughal Empire and illustrates this significant stage of Kashmir’s history as the key corridor of connectivity between the Valley and the Empire. The monuments to the culture of travel along the road represent the regional evolution and adaptation on Mughal architecture to create a convergence between local knowledge systems and foreign influences to generate a uniquely regional architectural vocabulary in terms of scale, functional ensemble, spatial planning, details, materiality, construction methods, and relationship with nature. The tangible remains of this exchange in cultural values are obviously manifest in the sarais, but call for greater research and archaeological excavation to find other building typologies that are known to have existed along this route as retaining walls, bridges, gateways, minars, fortifications, and water systems. The road is also an outstanding example of traditional human interaction with the environment as it navigates the fragile and increasingly vulnerable Pir Panjal landscape.

Risks

The key weakness of this cultural route is its lack of continuity that has resulted in diminished values of authenticity and integrity. While the drastically reduced usage of the road after the Mughal Era and its recent re-alignment has compromised on the authenticity of the road, its reduced integrity has been caused primarily by the lack of sustenance in usage and disintegration both of tangible assets such as heritage sites defining the route, and intangible assets such as public memory and oral traditions.

The physical condition, management context, and socio-cultural significance of the road are also key areas that require strategic interventions. While the decaying physical fabric of the route can be restored through protection, assessment, and conservation of both the natural and cultural landscapes, and the socio-cultural significance reinstated through education and awareness drives, it is the management context that is most challenging given the conflicted state of Kashmir and disintegrating international relations between India and Pakistan – the key custodians and stakeholders of the Mughal Imperial Road when perceived in totality. Poor international collaboration, politicisation of culture, funding constraints, lack of public engagement, and low prioritisation of heritage conservation are some of the issues that require to be addressed in times and places of conflict.

Need for conservation

While the Mughal Imperial Road heritage is not without issues, even with material and incorporeal losses, there remains sufficient vestiges of both quantity and diversity that with timely action can be used to understand the cultural route in its entirety, and establish its significance.

The Mughal Imperial Road is thus not only a means of transportation or communication, but an interactive, vibrant, and evolving channel connecting a diverse range of peoples, settlements, cultural centres, landscapes, and sites as a linkage surpassing limitations of physical distance and socio-cultural differences to create a rich natural and cultural milieu. It is through the acknowledgment and protection of the value of each of these intrinsic elements that the overall significance of the road be understood and its heritage conserved. It is then that the road can also cater to the contemporary social mandate for heritage to transcend its existence merely as a repository of natural and cultural values, and also function as a resource for social and economic development using sustainable tourism as a driver.

Further, the conservation of the Mughal Imperial Road calls for a model of conservation that recognises the road as a transboundary cultural property necessitating joint efforts, wherein in case of conflicting countries it becomes a platform for dialogue and potential tool for reconciliation. Though factually cultural routes have resulted from both peaceful and hostile encounters, they ultimately embody shared aspects that surpass their historic origins, creating the perfect context for a culture of concord, founded on shared ties of history, values, and the responsibility to preserve heritage for future generations that will reinforce tolerance, respect, and an appreciation for cultural diversity.

References

Bamzai, P.N.K. 2008. A History of Kashmir: Political–Social–Cultural from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Residency Road, Srinagar, Kashmir: Gulshan Books.

Bates, Charles Ellison. 2005. A Gazetteer of Kashmir. Residency Road, Srinagar, Kashmir: Gulshan Books.

Bernier, Francois. 1916. Travels in the Mogul Empire: A.D.1656‒1668. Translated by Archibald Constable. Oxford University Press.

Doughty, Marion. 1901. Afoot through the Kashmir Valleys. London: Sands and Company.

Findly, Ellison Banks. 1993. Nurjahan Empress of Mughal India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Gommans, Jos. 2002. Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and High Roads to the Empire 1500‒1700. Oxon: Routledge.

Hervey de Saint-Denys, Leon. 1853 The Adventures of a Lady in Tartary, Thibet, China and Kashmir. London: Hope & Co.

Hügel, Baron Charles. 2000. Travels in Kashmir and the Panjab Containing Particular Accounts of the Government and Characters of the Sikhs. Translated by Major T. B. Jervis. Delhi: Low Price Publications.

ICOMOS. 2008. The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. Quebec: ICOMOS.

Jahangir (Emperor of Hindustan). 1978. Jahangir-namah. New Delhi: Prabhat Prakashan.

Keenan, Brigid. 2006. Travels in Kashmir: A Popular History of Its People, Places, and Crafts. Delhi: Permanent Black.

Koch, Ebba. 2014. Mughal Architecture. Delhi: Primus Books.

Manucci, Nicola. 1907. Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653-1708. Translated by William Irvine. London: Murray.

Mehta, J.L. 2009. Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India, Volume II: Mughal Empire (1526‒1707). New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Private Limited.