There is one material that can lend form to objects as diverse as a piece of jewellery, a drainpipe, or a roof tile, it is baked earth, commonly known as terracotta. Versatile and beautiful, terracotta products have a fascinating history that can be traced back to the coastal villages and towns of South Canara and the Malabar. Terracotta tile roofing, one of the terracotta products is a distinctive feature of built landscapes in South India. Indian artisans have used terracotta as a roofing material for centuries, moulding it into potter’s tiles or country tiles. However, the arrival of the Basel Mission introduced a unique amalgamation of native and European elements in the terracotta craft of the region.

The Basel Evangelical Missionary Society, more commonly known as the Basel Mission, was a German evangelical group formed in Basel, present day Switzerland, in 1815. In the 19th century, it set up missions in European colonies across Asia and Africa. Operational in India’s Madras Presidency from 183l onwards (Basel Mission Annual Report 1871), the mission owes its uniqueness to the fact that it was as much an industrial enterprise as a religious one.

From 1831 to 1920, the mission was involved in several industrial and commercial activities in South Canara and the Malabar. They started with experiments in traditional practices like agriculture and weaving, later transitioning to modern crafts such as watchmaking, bookbinding, printing, and tile making. Many of the Basel missionaries came from rural and artisanal backgrounds; this shaped their view of the world, the importance land and labour had for them, and ultimately, the technical knowledge they transferred to artisan communities in Asian and African colonies (Stenzl 2010:13).

Industries of the Basel Mission

The Basel Mission established its first production centre in Mangalore, Karnataka, in 1834, followed by Dharwad, and Hubli in 1837, and Kerala in 1841 (Basel Mission Annual Reports). Between 1834 and 1914, the mission expanded its industrial initiatives. Having ventured initially into agriculture without success, for their later activities they focused on the traditional crafts practised in the region.

This early phase of industrial activity was solely the initiative of the missionaries. A lithographic printing press was set up in Mangalore in 1841. In addition to the religious texts it produced, the press also received government documents for printing. Thus, the printing and bookbinding became the principal activities of some of the mission’s oldest workshops. In the 1840s, they ventured into agricultural industries like coffee, oil, sugar, and silk, besides clockmaking. Weaving was added to the mission’s repertoire in 1847 by Johann Metz, a missionary who was a weaver by profession. In 1851, master-weaver Jacob Hallen was sent to India by the mission to use and combine local and European knowledge in order to develop their weaving establishments.

In the same year, the mission entrusted George Plebst, a mechanic by training who later specializes in printing, with the task of launching a letterpress unit in India. The press he established in Mangalore produced and printed documents in Kannada, Malayalam, and Tulu (Stenzl 2010). It was Plebst who perceived that the rich earth of the region and the existing terracotta craft tradition could be used to further expand the mission’s industrial ventures. Subsequently, the first tile-making workshop was set up in 1863 in Jeppu, Mangalore. This was a small unit with a handful of employees who not only produced tiles, but who also experimented with making various terracotta products for the market of the time.

Hence, in the Basel Mission’s 19th century workshops, native and European knowledge, practices, and modes of cognition coalesced into a common culture, a new industry with products that were both innovative and adaptive. Plebst implemented his plans for tile making and pottery on a small scale in the Jeppu workshop. He began collaborating with an Indian master-potter, and together they built an oven and started experimenting to ascertain the optimal mixture of clay and sand for terracotta products. In 1865, the workshop produced about 360 tiles a day with two workers and a few bullocks. It was the first of many such establishments in the region, which were followed by hundreds of factories.

Thus, the Jeppu tile workshop was the seed from which germinated one of the largest industries in the region, which derived its sustenance largely from the Indian soil and indigenous skill, although in the early years the workshop relied heavily on Plebst’s expertise. In 1880, steam power replaced bullocks, marking the transition from handmade tiles to mechanised tile making. Consequently, production in the Jeppu unit rose up to a million tiles per year. Mechanisation and centralised production changed manufacturing processes irrevocably, as well as the aesthetics of terracotta products.

Terracotta products of South Canara in the 1800s

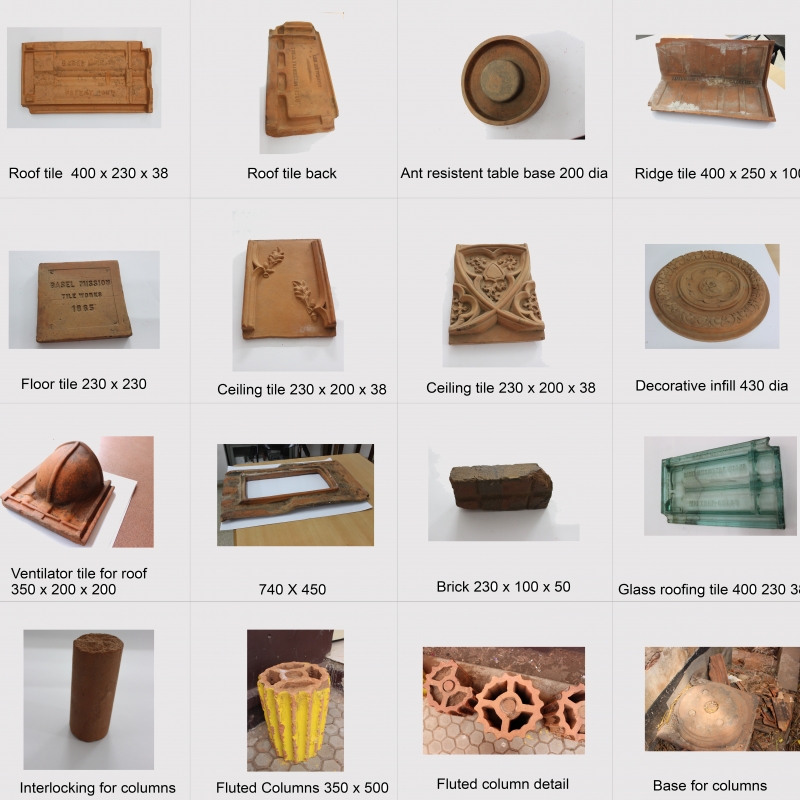

In 1907, the Basel Mission workshops employed as many as 3,600 people, and by 1913, it was the biggest industrial entrepreneur in South Canara (Stuart 1895). Mechanisation involving steam power or the gas kiln enabled the mass production of uniformly proportioned terracotta products. These included roofing tiles, ceiling tiles, balusters, drainage pipes, bricks, columns, flooring tiles, decorative ridge tiles, vases, and decorative pots. Each of these products was made with soil from the banks of the Netravati river, using local skill and labour, and adapted to the German designs that Plebst had brought with him.

The Mangalore roofing tile was without doubt the Basel Mission’s most popular and widely used machine-made product. Prior to its advent, potters had handcrafted each tile on the wheel or with moulds. The soil was kneaded by hand to a malleable consistency before it was placed in the wheel to fashion cylindrical pieces, which in turn were cut in half to make semi-circular tiles. The standard potter’s tile of the region measured 200 × 80 × 50 mm. However, handmade tiles from the same batch tended to vary slightly in their shape and dimensions, depending on the type of local soil used as well as the skill of the craftsman. The machine-made tiles were precisely proportioned and uniform. A collection of the various products of the Basel mission is housed in the KACES campus in Mangalore and is ardently collected and maintained by Bennett Ammanna, an archivist with decades of experience in the region.

Manufacturing process of the Mangalore tile

The manufacturing process of the Mangalore tile, first adopted in 1865 in the Jeppu tile factory, has not changed significantly to date. However, the mechanisation of the industry, primarily the use of highly efficient kilns, has made it possible to produce a larger number of tiles in the 1865 design and mould within a shorter space of time. The manufacturing process includes the following processes: the preparation and processing of the clay, the pressing of clay slabs into tiles, and finally, kiln firing are the main processes involved in making of the tile. The machines essential to operating a tile factory are (i) the pan mill, (ii) the pug mill, (iii) the tile press, and (iv) the kilns. There could be many variations in this process but the essential stages are described below (Mani 1990).

a) Weathering

Any clay used for making tiles has to be weathered by the natural forces of wind, sun and rain. The moisture content of the clay, the homogeneity and the consistency of the clay increases by this process. The clay is normally exposed to natural climate for a year, traditionally before it is used (Mani 1990).

b) Souring

After weathering, the clay is removed and placed in souring pits. Tile factories normally have two or more pits for this purpose. The clay is put in layers for up to 15 days.

c) Mixing and grinding

A box-shaped feeder is usually used for this purpose, with tubes and blades for cutting and shearing the lumps of clay.

d) Pug mill

The pug mill is a machine used to grind the clay in the required consistency to produce tiles. The machine mixes the clay and the homogeneous clay is extruded into long cubic sections. The stickiness of the clay needs to be controlled by smearing oil on the blocks. This also makes it smoother. These blocks are then cured for a couple of days before they are pressed into moulds.

e) Pressing of tiles

The pressing of tiles is done with machine press in factories. The pressing of tiles is one of the most important processes of the entire sequence of tasks as the tile takes the desired shape and size in this stage.

f) Drying tiles and kiln firing

The pressed tiles are dried before they enter the kiln for firing. At this stage, the tiles are baked in a kiln until each of them attains sufficient hardness and strength. Since tiles are usually produced in large quantities, large kilns containing multiple chambers are a prerequisite for an economically viable factory. The tiles are removed and arranged in sets inside the kiln chambers for firing. The proper setting and drawing of the tiles, and the firing and regulation of temperature within the kiln, require knowledge and experienced workers. The temperature sutaible for firing ranges from 8000°C to 9000°C.

Modern tile factories use continuous kilns, also known as Hoffman kilns. These facilitate greater economy in firewood consumption, as the ware is constantly circulated through a single extended chamber recycle the heat. Semi-continuous kilns with series of interconnected chambers are the newest innovation in the roofing tile manufacturing, with benefits over both intermittent and continuous kilns (Mani 1990).

The cultural process of tile making

How an object is made describes and reveals the maker. Therefore, technique, in the crafts, is a cultural process in addition to being a mundane objective procedure. The story of tile making, passing from the hands of traditional potters into those of skilled workers in modern factories, attests to that which Richard Sennett describes as the historical relationship between the craftsman and his material: ‘The craftsman’s consciousness of materials appears in the long history of making bricks, a history that stretches from ancient Mesopotamia to our own time, a history that shows the way anonymous workers can leave traces of themselves in inanimate things (Sennett 2008:10).'

Hence processes of production are intimately linked to culture-specific materials and skills, meanings, and modes of cognition. Ways of working and making are shaped not only by the material in question but also by changing means of production over time. In the case of the terracotta products of the Basel Mission and especially the Mangalore tile, processes of making had transformed the product itself. The semicircular potter’s tile evolved into a flat, interlockable tile that came to be known as the Mangalore tile, still produced in the region although in significantly smaller numbers. Today, the tile is a characteristic feature of the built landscape of the region, and the processes of its making is a vital part of its lived heritage.

Conclusion

Many a rural landscape in present-day Karnataka and Kerala, where the production of the Mangalore tile was pioneered in the 1860s, is still adorned by these red tiles. Architects who design and build structures in traditional styles employ them as roofing material. Though concrete roofs have largely replaced tiled roofs and other types of native roofing, the nostalgic and emotional value attached to this tile in the cultural landscape of these regions is so strong, even today, that it is often used as cladding for concrete roofs. Rather than serving a functional purpose, the Mangalore tile in these contexts evoke a sense of belonging and identity for urban dwellers. Thus, the story of the making and transformation of terracotta tiles, initiated by the Basel Mission in the South Canara region more than a century ago, has become an intrinsic part of the tangible and intangible heritage of Karnataka.

References

Basel Mission Annual Reports. 1864–1875

Mani, K.P. 1990. ‘Tile Industry in Kerala: Economics, Problems and Prospects’. PhD thesis. Department of Economics, Cochin University of Science and Technology.

Sennett, Richard. 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Stenzl, Catherine. 2010. ‘The Basel Mission Industries in India 1834–1884’. Master’s thesis. Department of History, Birbeck University of London.

Stuart, Harold A. 1895. Madras District Manuals: South Canara. Madras, Government Press.