Introduction

Native architecture reflects the needs, skills, culture, and material resources of a region. The most fascinating pieces of architecture are often not state monuments but the dwellings of commoners, which are seldom regarded as unique marvels. Most of the world’s architecture is still made by local communities, using local resources. Different regions present beautiful, versatile ways of using building material to its full potential. Paul Oliver’s (1997) work, Encyclopaedia of the Vernacular Architecture of the World, is an attempt to bring many, if not all, vernacular examples together. Architecture as a discipline is generally viewed as innovative or unique ways of building. This leaves little room for the humble vernacular buildings made by communities in accordance with local traditions.

The concept of vernacular architecture as ‘people’s architecture’ emerged in the later 20th century (Oliver 1987). Interest in the vernacular often accompanied a critique of the contemporary architectural practice of the time (Vellinga 2007). To many, contemporary architecture seemed disconnected from humanity and ethics. If ‘vernacular’ has to be defined from Oliver’s perspective (an architect who has extensively written on vernacular architecture), it would mean the native science of building. However, in the discipline of architecture, the meaning of vernacular requires a qualitative understanding. The native buildings are constructed to provide solutions to a specific community or even family, using precise methods, which have been identified by the immediate community and modified by each successive generation. For thousands of years, vernacular knowledge built upon the know-how of previous generations and crystallised into the architecture of the present; however, one event in the history of making changed the narrative to a great extent—the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution aided the transition from handmade to machine-made. Mechanisation altered the processes of construction, weaving, printing, and countless other processes in the 19th century and early 20th century. As the processes of making changed, mass production replaced native, vernacular methods, which are highly relative and yield architecture true to the context and people. This article locates some examples of the vernacular and traces the transition from handmade to machine-made in the architecture of South India. The examples elaborate on the tectonics of various native and colonial techniques of construction that have constituted the built landscape of India and which have eventually become a part of its built heritage.

Material and need

South India and most of Karnataka and Kerala, where the architectural examples are located, are especially resource rich. Granite, earth, and bamboo are available extensively. The landscape of the south is speckled with examples of dwellings made of mud, bamboo, stone, and variations and combinations of these materials used in diverse patterns. The walls and roofs are made from the above materials with visually striking lime mortar and plaster, which were considered of a very superior quality in the 18th century (Dharampal 2000). The materiality of buildings is deeply linked to the techniques used in native building. Each form derived is appropriate to the material, its strength, and the need of the user.

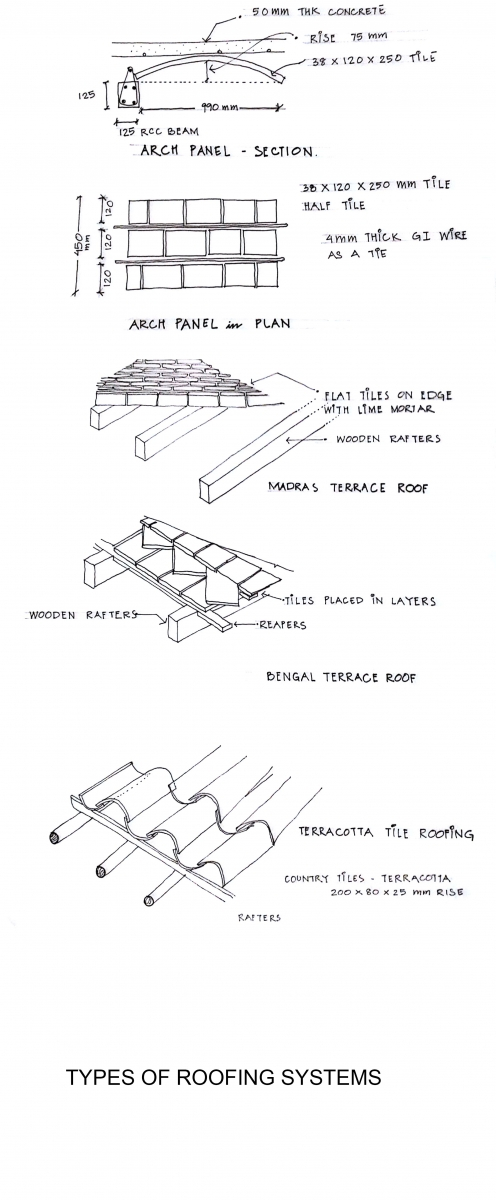

The South Indian vernacular has fascinating examples of architecture using a variety of materials and techniques. Thatch/grass is one of the earliest found materials used to cover shelters. Local, mature grass reeds are cleaned, dried, tied, and woven to be used as roofing. It is still used in varied roofing techniques, but alternate materials have replaced thatch roofs over the last two centuries. The history of roofing in most of South India starts with basic woven thatch roofs and then progresses to roofs in trabeated stone (with beams and columns). Most regions of Karnataka are rich in stone. These roofs have layers of dressed stone slabs. The other kinds of roofs in the region are made of bamboo and mud, which are combined with various local leaves to make the roofs waterproof. In the 18th century, examples of Madras flat terraces—which were much more structured roofs made with burnt brick, wooden rafters, and lime plaster—were common.

Another system of roofing that was introduced in India in the 19th century was jack arch roofing or arched panel roofs. The earliest examples of jack arch roofs are found in Asia. These roofs are made with flat bricks or tiles placed along radiating panels in between beams. The flattish arch is supported on wooden or steel beams. These roofs were advantageous, as construction involved small elements and could be done by individuals. Interestingly, this technique became popular during the Industrial Revolution, as the abundance of steel that was produced could be used to make ‘I’ section beams. The excitement associated with using steel was probably greater than the necessity, at the time. The availability of steel and the British engineers’ bias towards using it in buildings made jack arch roofs popular.

The above-mentioned roofing types were not the only ones prevalent during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries; regional craftsmen and British engineers in India were conducting other experiments as well. The reinforced brick roof was a variant in the early 20th century. The use of terracotta tiles in roofs probably has a longer history than any other material, and it continues even today. This handmade, handcrafted material has regional variations, according to the type of soil, the skill of the craftspeople, and climate. The transition from handmade to machine-made was significant in the 19th century, especially in the case of terracotta tiles. Like most other objects that evolved from being handmade to machine-made, terracotta tiles changed the built landscape of South India, they began to be used at a much larger scale.

Examples of each type of roofing exist even today in South India, though some are in dilapidated conditions and will soon be erased altogether. The examples demonstrate the tectonics and their relation to the material. The strong link between handmade materials and vernacular methods of building is evident in each of the examples below.

Stone roofing: Mantapa at Guluru, Tumkur district, Karnataka

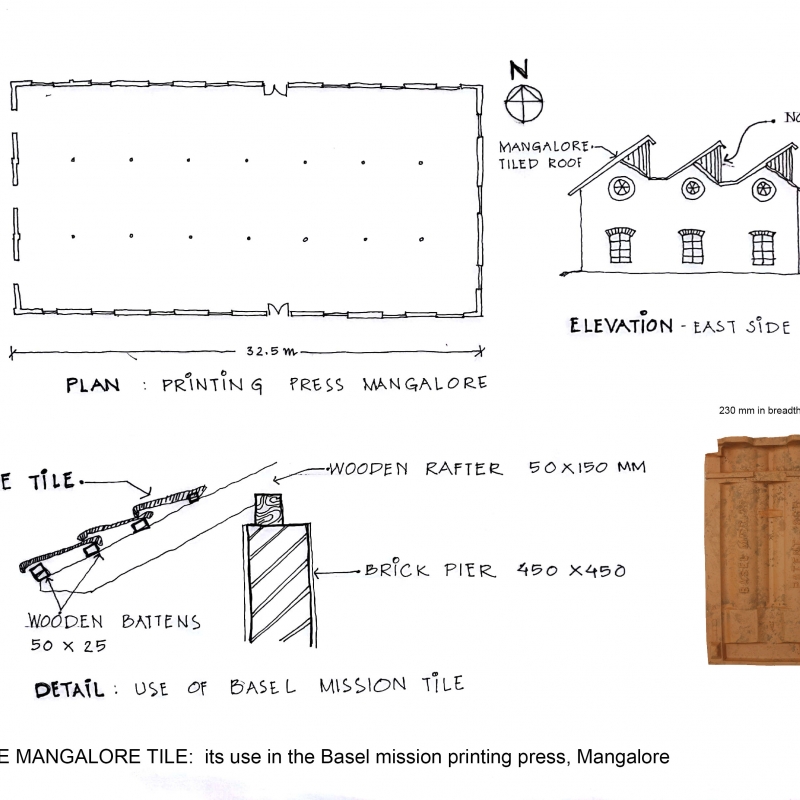

This structure was constructed at least 500 years ago and surrounds a large open court. The shelter was originally used as a mantapa, but it is currently dilapidated and in ruins. The walls are made of cob. The roof is made with granite stone slabs secured in layers with mud. Local craftsmen used whatever was easily available within a small radius of the site to create this structure.

Fig. 1: Plan and section of the Gulur Mantapa in Tumker: Stone and mud construction system

Fig. 2: Gulur Mantapa entrance

Mud and bamboo roofs: Kaidala houses in Tumkur District, Karnataka

The houses are about 150 years old and are made with abode construction and stone in this region. The typical house here is normally rectangular, with wooden columns placed three meters apart in one direction and two and a half meters apart in the other. The houses include space not just for human habitation, but also for livestock such as goats in the house. The roof of the house is made of two layers of locally available wood with about 40 cm of mud placed on top. The two layers of bamboo, placed at 90 degree angles to each other, provide stability, and the thick mud layer on top prevents rainwater from seeping in. It is one of the most efficient methods of roofing in hot and arid regions, as the roof is thick, which prevents heat penetration.

Fig. 3: Cob wall in Kaidala, Tumkur, Karnataka

Madras terrace Roof: House in Devanahalli Fort, Bangalore, Karnataka

The house is located on the main street inside the fort built in 1750s in Devanahalli. According to the 1981 Karnataka Gazetteer, the original fort was built in about 1501 by Mallabhaire Gowda of Avati with the consent of ‘Deva’ (a feudatory at Devanadoddi), who changed the name of the place to Devanahalli. In 1747, the Mysore dynasty conquered Devanahalli. The Marathas later conquered it several times, thus winning it from Mysore. The remains of this fort were formerly seen inside the present fort. The present fort, with its large, tall walls and bastions, is ascribed to Haider and Tipu Sultan. Tipu Sultan also changed the name from Devanahalli to Yousafabad. The fort was made of stone, brick, and mud, constructed in the form of an oval, flanked with circular bastions and two cavaliers on the eastern face. It was not quite complete when Lord Cornwallis’ army laid siege to it in 1791—it easily submitted (Gazetteer of Mysore 1981).

The house placed inside this magnificent fort is about 120 years old—it has granite walls and Madras terraced roofs. It has an interior central room with raised walls and habitable rooms all around. Ventilated walls light the space. The entrance of the house has a jaggalli (raised porch) with a mud and wood reaper roof. The interior of the house has a Madras terrace roof, which is made with layers of wooden beams, bricks kept on their edges finished with a mixture of broken brick, pieces of stone called ‘jelly’, and lime plaster.

The flat terrace method of roofing has been in practice in most of South India since as early as the 18th century. Now considered native and vernacular, it was originally the result of an intersection of native and British engineering techniques. The use of burnt bricks laid on their edges and put together with lime is another technique in the history of roofing systems. In this method, wooden beams are placed about two feet apart. Then, flat bricks are placed on their edges, diagonally—these are bonded with thick lime mortar. Another variation of this roofing technique, called the Bengal terrace, can be seen at St. Andrew’s Church in Bangalore. There was a constant mixing of vernacular and British building practices in 19th century India. The Madras terrace roof probably evolved from thatch, bamboo, and unstabilised mud roofs. This kind of roof resisted rainwater, fire, and the constant need for replacement, which was required of earlier roofs.

Fig. 4: Madras terrace roofing in Devanahalli houses

Jack arches

Jack arch roofs or arch panel roofs emerged subsequent to the Madras terrace roof—these could be used for longer spans of time and consisted of a combination of bricks and steel. British engineers were instrumental in making this kind of roof popular. The roof consists of steel ‘I’ section beams with gaps of about two feet between them, in which arched panels of terracotta tiles/bricks of different sizes are placed. The panels can be made on the ground with thin steel reinforcements and placed on the ‘I’ sections. The roofs became popular in the early 20th century, as they could be made in small sections, with lightweight material. The availability of steel made the roofs easy to assemble. Jack arch roofs are among the first examples of roofs made with steel.

Potter’s tiles on wooden trusses: Sural Palace, Udupi, Karnataka

Potter’s tiles are some of the oldest materials used in roofs. From Greece to India, most civilisations have used this method of moulding clay on a wheel and firing it to make roofs. The tiles were made using varied techniques and types of clay in parts of South India. For example, the tiles made in coastal Karnataka differed in colour, shape, and size from those made in Tamil Nadu or Andhra Pradesh. The beauty of the material lies in the diversity of the end product, depending on the quality of the raw material and the maker’s skill. Potters made tiles by hand as they had a good understanding of the soil in specific regions.

One technique is to make the tile as a cylinder on the wheel and cut it into two halves; the other technique is to roll the clay into sheets and put it in a wooden mould in the shape of the tile. The different elasticities of soil across different regions impacts the shape and size of each tile. Mangalore is especially important for the history of tile making, as it was the first place where mechanical/factory production replaced handmade processes. The Basel Mission, a German missionary who arrived in India first used mechanical processes to make tiles, in Jeppu, Mangalore in Karnataka. Steam power was introduced in 1881, while the first factory for making these terracotta tiles was set up in 1865 (Raghaviah 1990).

Fig. 5: Handmade terracotta tiles found at Sural Palace

Sural Palace is an example of a building where handmade potters’ tiles are used. The building is about 500 years old and was built by Tulu Jain Tholahars. Jackwood wooden trusses are used with wood joinery. The palace has three different building elements, namely the angalas (courtyards), the pattada chavadi (royal durbar room), and also a mini-shrine. The roof is made of layers of handmade terracotta tiles. The adobe walls are 60 cm thick, and they support the wooden roof trusses. The tiles used at the gutter/storm water drain have larger radii. The larger radii allow for the easy flow of rainwater. Interestingly, during the renovation process, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) introduced Mangalore (or mechanised) tiles in the roofing. Handmade potters’ tiles were used in the original palace roof.

The South Canara Gazetteer (1895) provides a great deal of detail on local potters—there were thousands in the South Canara region, and hundreds of brick and tile merchants. Every village in the region produced pottery and tiles to use for roofing during the 19th century. The Uppinangadi village was particularly famous for its superior quality of tiles and pottery; the potters were called Kumbaras, and were divided based on whether they spoke Kannada or Tulu.

The pottery in Uppinangadi was made with powdered clay mixed with water. The village had the Kumaradhara River on one side and the Netravati River on the other; both riverbeds had soil suitable for tile making, as it was malleable. The clay was poured into a specially prepared pit, where it was allowed to remain for about a month, by which time it became quite dry. It was then removed, powdered, moistened, and made into balls, which were placed one by one on a wheel and fashioned into various kinds of vessels, including vases, goblets, teapots, cups, and saucers. The vessels were dried in the shade for about eight days, following which they were baked for two days. They were glazed and sometimes ornamented. The poorer classes generally used ordinary earthen vessels, as these were relatively cheap. A potter would earn, on average, about five annas a day in 1895. The Gazetteer’s detailed description indicates that the scale of a potter’s tile production was small (Stuart 1895).

Mechanisation of the tile making process by the Basel Mission

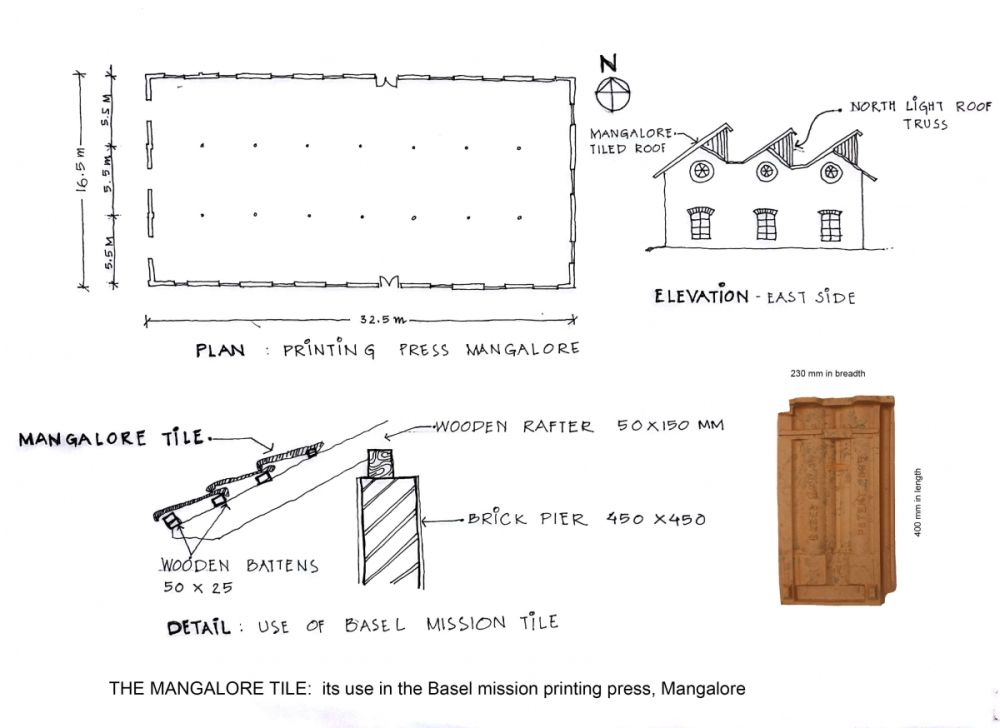

Country tiles were among the most popular roofing materials in much of South India during the 19th century. The introduction of the machine-made tile—popularly called the Mangalore tile—changed the built landscape of South India. These were flat, fired clay tiles, which interlocked and were laid at steep angles. The story of the mechanisation process of fired clay tiles, which had previously primarily been handcrafted, is an interesting one, as it incorporated vernacular knowledge, resources, and skills with those of the Western world, at the time.

The Basel Mission started producing the first machine-made tiles in 1865. A small factory with two workers producing a few hundred tiles each day was established in Jeppu, Mangalore, by George Plebst of the Basel Mission. Initially, factories produced flat tiles that were different from the curved and grooved type, which are still used for roofing. Subsequently, the factories manufactured ridge tiles, both plain and ornamental skylights, ventilator ridges and hip terminals, finishes of various kinds, grooved spherical tiles, hanging wall tiles, and ceiling tiles of various designs. Hourdis (ceiling slabs), common and ornamental clay flooring tiles, chimney bricks, salt glazed stone, earthenware, drainage pipes, terracotta vases, flowerpots, and other products are on the long list of items that the factory produced.

The Mangalore tiles had interlocking edges and were flat. They were manufactured with the same mould. Even smaller building owners used the tiles. These tiles were used in many public buildings, which provided a new and desirous finish. From 1868, the tile industry started facing local competition. By the 1870s, Kappaya Bhandari and Alex Albuquerque had established tile factories in Mangalore—they were local entrepreneurs who produced tiles with a similar design to that of the factory in Jeppu (Raghaviah 1990:43). The name ‘Mangalore tile’ is still popular in the construction industry.

The tile manufacturing process includes preparing and processing the clay, pressing clay slabs into tiles, and finally, kiln firing. The plant and machinery required to run a tile factory today are a pan mill, pug mill, tile press, and kilns. There are considerable variations in the efficiency of each of these systems, depending on their degree of sophistication. The factory in Jeppu conducted all the processes of tile making, such as weathering, souring, mixing and grinding, pressing, drying, and manual kiln firing. Slowly mixing and grinding became steam powered, and pressing was done with handheld machines. The kilns also became more sophisticated, with machines to transport items in and out of them.

The transition from handmade to machine-made reflected in the built landscape of South India in the late 19th century. Even today in Mangalore, many roofs are made with fired clay tiles—they became a part of the built heritage of the region. The change in processes further shaped the way the architecture changed. The tectonics had a constant influence on the style of architecture.

The popularity of the Mangalore tile has reduced in the last few decades, as reinforced concrete roofs—made with concrete and steel—have begun to dominate built urban landscapes. The easy availability of cement and steel, the ease laying concrete roofs, and the standardisation of processes have made RCC (reinforced concrete cement) a common sight. Cement and its tendency to mould into any form makes it almost characterless in comparison to other materials, such as thatch, clay, or stone. Each of these natural materials has its own strengths and limitations, which makes the creator’s skill an important factor in the architectural process.

The nostalgia associated with the Mangalore tile and its connection with vernacular architecture is so strong that urban landscapes often have concrete roofs with Mangalore tiles that are more ornamental rather than functional. The Mangalore tile, which was originally manufactured only in one size in 1865, is made today in at least 10 different sizes, so that it can cater to the designs of recent buildings.

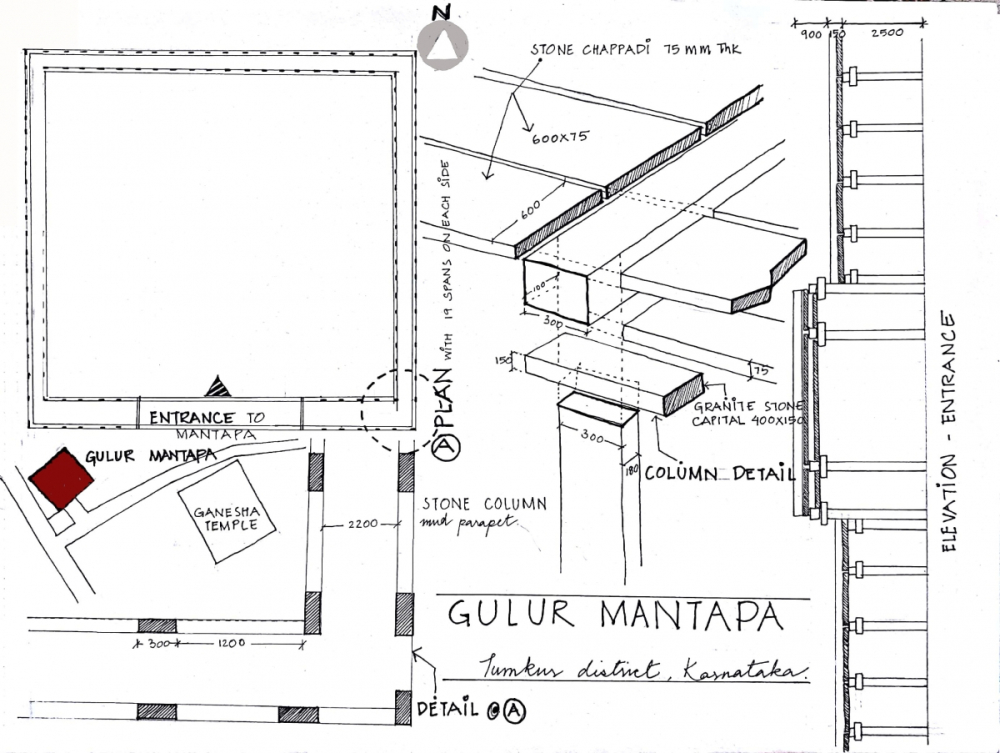

Machine-Made terracotta tiles on trusses: Printing Press, Mangalore, Karnataka

The Mangalore printing press building, built by the Basel Mission around 1900 (originally a weaving unit), uses Mangalore tiles and demonstrates the regular, symmetrical, and standardised form of architecture. The building has bricks made by the Basel Mission factories in the walls, clay ceiling and flooring tiles, and the Mangalore tiles on wooden trusses. The building is rectangular, with wooden rafters at regular intervals; the Mangalore tiles sit on the rafters. The high walls support a north-facing light truss. The strong symmetry of the building is a consequence of the machine-made components. The tectonics in the building are a result of the material and its form.

Fig. 6: Drawings of the Printing press building 1901: Mangalore

Conclusion

South India’s architectural heritage is intricately connected to the history of technology. Native techniques and construction processes are knowledge systems which are embedded in the architecture of the region. Changes in technology, the needs of people, and the social structure of society have all contributed to changes in architectural styles and practices. This common built heritage, in the case of just one component, i.e. roofs, indicates the rich and intricate relationship that technique, technology, and construction processes have to the finer nuances of architectural style and language. Tracing the historical trajectory of technology and the tectonics of different societies gives architecture and built heritage a renewed meaning.

Glossary

Bengal Terrace: A kind of flat terrace that was used in Bengalthe technology was transferred to various other regions in India. The terrace uses wooden reapers and flat bricks with lime.

Madras Terrace: flat terrace similar to Madras terrace but has rafters with large and bricks on edge laid in lime mortar.

Mantapa: A shaded platform, made with series of columns for various purposes of shelter.

Adobe Construction: Construction done with earth based techniques.

References

Dharampal. 2000. Indian Science and Technology in the Eighteenth Century – Some Contemporary European Accounts. Mapusa, Goa: Other Indian Press.

Oliver, Paul. 1987. Dwellings: The Vernacular House World Wide. Phaidon Press. New York, USA

Oliver, Paul, Marcel Vellinga, and Alexander Bridge. 2007. The Atlas of Vernacular Architecture of the World. Routledge. London. UK.

Raghaviah, Jayaprakash. 1990. Basel Mission Industries in Malabar and South Canara 1834–1914. A Study of its Social and Economic Impact. p. 43. New Delhi: Gian Publishing House.

Sunil Kumar, Fedrick. 2006. The Basel Mission and Social Change–Malabar and South Canara: A Case Study (1830–1956).University of Calicut, Calicut, India.

Stuart, Harold A. 1895. Madras District Manuals. South Canara. Madras: Government Press.