Today, the idea of getting through even a single day without the use of machines is inconceivable. No aspect of contemporary life is untouched by mechanisation. Since the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century, machines have transformed humankind’s physical environment as well as their mental landscape, constantly reshaping human needs and desires. It is not surprising, therefore, that architecture—its fundamental forms and functions—have undergone a metamorphosis in the age of mechanisation.

The influence of mechanisation is visible mainly in three aspects of modern architecture: the types of material used; the culture of adornment, substitution, and imitation; and the changes wrought by mass production. The Industrial Revolution created new, hybrid building materials that raise interesting questions about the ways in which both makers and users engaged with architecture: did these modern materials enhance the possibilities of using and understanding material, or did they deteriorate users’ tactile and emotional experience of material? Secondly, new modes of embellishing spaces, and of substituting and ‘imitating’ materials and products, have altered architectural spaces. Lastly, mechanisation, characterised by a shift from handicraft to mass production, transformed the nature and economy of architectural practices.

The literature on tectonics in architecture explicates the vital link between material and design (Giedeon 1948). It is interesting to examine the nuances of design using natural materials like earth, thatch, and wood, vis-à-vis designs made for machine-made materials such as cement or steel. For instance, earth is a material that can be mixed with water and other additives to change its consistency, and it can be moulded into certain forms; however, it has limited elasticity and malleability. It gives definite form to its products but imposes limitations at the same time. Therefore, an understanding of the characteristics of this material becomes essential for effective design. Similarly, thatch is just a reed when reduced to a single unit, but tied together in bundles, it can function as building material for roofs of any desired shape or size. This is a natural material that is very different from earth or wood. Yet wood, unlike earth, can be cut into pieces and joined, the sections assembled and fixed in definite geometries.

In other words, natural construction materials call for tactile and emotional appreciation and investment on the part of the maker. This changed with the invention of Portland cement in the 19th century. Cement could be made into slurry and moulded into any form or size that the human mind was capable of imagining. Once cast in a mould, it hardens rapidly to acquire the desired shape. At the time that it was invented, a material like cement, which possessed no inherent quality but that of moulding itself to the required form, was a novelty. The complex properties of these new materials would change the practice of architecture significantly in the centuries that followed.

The second major change wrought by mechanisation was a tendency towards excessive adornment, made possible largely through the emergence of new technologies that facilitated substitution and imitation of materials. Sigfried Giedeon, an historian of architecture, argues that mechanisation has confused our cognitive faculties and has cluttered our built environments through the industrial manufacture of artifacts, adulteration of handicraft methods, and the consequent degradation of our sense of materials. The urge to adorn the body, objects of everyday use, and one’s dwellings, is intrinsic to human nature. However, machines enabled the mass production of objects, which in turn reduced the cost of goods and encouraged the desire to clutter and over decorated built spaces.

Adornment is no longer linked to toil, time, and craftsmanship, as it had been in traditional contexts; it is now mass produced, and the cheaper its production becomes, the more it thrives, in the form of vases, vessels, carpets, furniture, and architectural facades (Giedeon 1948). From art objects like statues to the surfaces of buildings, from the plaster on the wall to the flooring of a room, everything is now excessively embellished. After the Industrial Revolution, this trend was not limited to the upper classes, or to any particular economic section of society. If the rich used gold to adorn their living spaces, the poor were content with iron, but the love of excessive ornamentation and the loss of a sense of materiality prevailed almost universally. This culture of adornment persists even today, despite the efforts of some contemporary architectural practices and scholarly initiatives to shake it off.

At no time in history was the imitation of the handicrafts easier than in the 19th century. The sheer number of patents that were granted in Britain, especially in the mid-1900s, attests to the rate of technological development made possible by mechanisation (British Patents). In the construction industry alone, patents were issued for stamping, embossing, pressing, punching, and coating of objects. This meant that it was now possible to conceal bad craftsmanship and low quality products with expensive coating material. The new factories were producing objects that ‘imitated’ artifacts fashioned using skill and effort involving time and labour. A whole range of substitute materials and imitation goods thus flooded the market, changing public taste and, over time, the very aesthetics of built environments.

The third aspect of mechanisation in architecture has to do with its economics. If there could be a patent for a technique to ‘better the production of Indian or Venetian carpets’, there could be much deeper influences of mechanisation on architecture. Where guilds or the families of a particular community were traditionally engaged in a particular craft, such as pottery or carpentry, the cost of the product included the value of the labour, skill, and material that had gone into its making. The factory system of production changed the economies around produced objects. Prices were not fixed like in a guild, but reduced with the quantity of the product produced. As a result, products were diminished in emotional and social value while their material value remained. When identical objects were produced in mass, an individual’s attachment to personal objects came to be valued more in terms of cost than in terms of value.

Mechanisation and taste in architecture

At the ‘Great Exhibition’ of 1851 in London, a structure fashioned entirely of glass and metal, on display for the first time, took centre stage. Henry Cole and Joseph Paxton had collaborated to create the Crystal Palace, an archetypal image of mechanisation and the beginning of a new materiality in architecture in the industrial era. This exhibit probably marked the beginning of the extensive use of glass in architecture. Materials gained a new meaning in the 1850s. The exhibition was structured in ways that invited spectators to compare Oriental handicrafts with British machine-made products.

In retrospect, the Great Exhibition raises questions about the impact of mechanisation on public taste. Can systems of production, their methods and materials, alter the aesthetic of users and their built spaces? The question is particularly relevant in today’s contexts. Henry Cole observed: ‘At the exhibition the visitor will see flowers and leaves and fruit of a size such as was never seen in this world before. He will find his eyes dazzled and perplexed by moss-roses that give him a headache with their brightness’ (Cole 1851).

Cole’s comment was a remark on mechanization and its by-products. Over-embellished architecture in urban India and elsewhere in the world poses similar questions regarding the repercussions of mechanisation in terms of material, taste, and practicality. The variety of low-cost building and cladding material available on the market today has made adornment both accessible and affordable. This often leads to impractical or gratuitous architectural choices such as glass facades in tropical climates, large windows that cause excessive heating of indoor spaces in arid regions, or brickwork walls covered in cheap plaster or one of the zillion new materials that guarantee users heavenly benefits.

Tiles, bricks and bread: Mechanisation and uniformity

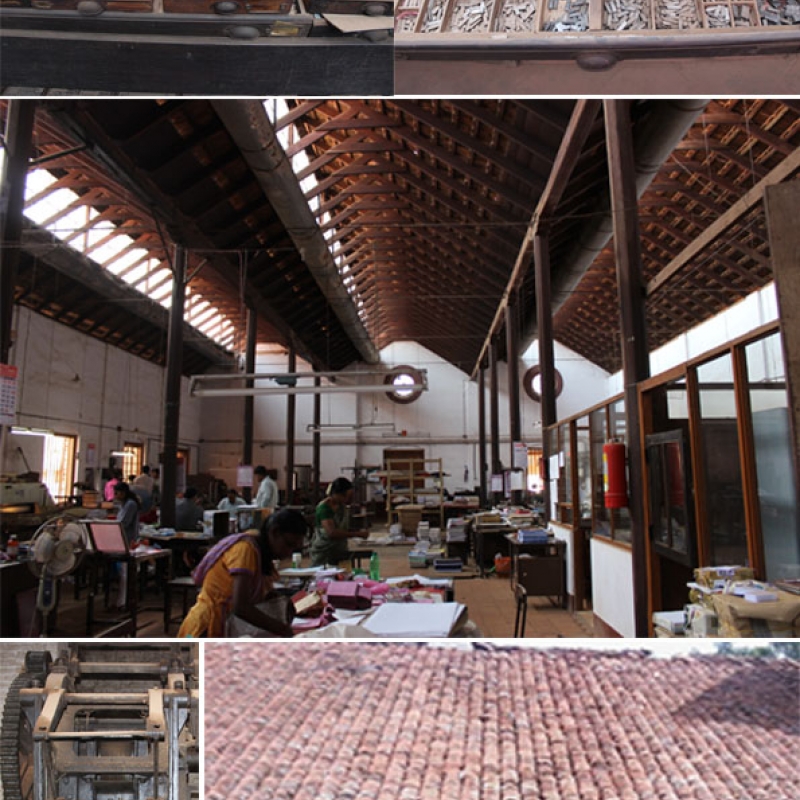

Tiles and bricks are among the most common units of construction in architecture. Terracotta roof tiles have long been an integral part of South Indian built landscapes and continue to be used, though they are increasingly supplanted by concrete roofs today. In 1865, terracotta tile making was mechanised by the Basel Mission in Mangalore, a development which transformed its form, production, and use in the region forever. Similarly, bricks were mechanised and standardised like several other products of the time. Many manual processes, including printing, weaving, and even food production, were taken over by machines in the 19th century.

The mechanisation of bread making, in many ways analogous to that of tiles, illustrates how public tastes were altered by the transition from manual to manufacturing processes, which generated a new desire for uniformity. For instance, the public were not initially particular about the colour of bread crusts, but as any required tint could now be precisely obtained by means of thermostats and added ingredients, it became the norm to expect evenness of colouring in machine-made loaves. Similarly, in the case of tiles, mixing, pressing, and kiln-firing were mechanised, shifting from hand-operated or bullock-driven processes to steam power. The press machine used identical units of clay with the same consistency and baked them evenly in the kiln to produce tiles of the same appearance, weight, density, and strength. These qualities may not be essential while building a roof but, over time, uniformity—whether in tiles, loaves, or bricks—came to be seen as a desirable feature.

Machines, art, and architecture

The main source for this article is Giedeon’s saga of the machine and its effects on many facets of human life; these theories have in turn been applied to architecture and its relation to material. Since the 19th century, many artists and architects have drawn inspiration from the products of industrial technology and the factory system, enthralled by their efficiency and precision. In 1922, the Futurist painter Gino Severini wrote: ‘…the precision of machines, their rhythm and their brutality, have no doubt led us to adopt a new form of realism’ (Severini 1975).

Modernist painters who rejected the conventional notion of the aesthetic, like Kazimir Malevich or Amédée Ozenfant, found value in the geometric forms evoked and created by machines: ‘A mechanical object can in certain cases affect us, because manufactured forms are geometric, and we respond to geometry…’ (Ozenfant 1952:151). The Industrial Revolution moulded the imagination and practice of these artists, and architects were not far behind. It is not surprising, therefore, that the advent of the machine and the diverse contexts of its use in the 19th century reshaped ideas, processes, and spaces in architecture, restructuring both its economy and aesthetics. This is an ongoing transformation, one that is likely to continue far into the future.

References

Cole, Henry. 1851. The Journal of Design and Manufactures- Vol IV. Chapman and Hall. London, England.

Giedeon, Sigfried. 1948. Mechanization Takes Command: A Contribution to Anonymous History. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Giedeon, Sigfried. 1967. Space, Time and Architecture. The growth of a new tradition Minneapolis: Harvard University Press.

Ozenfant, Amédée. 1952. ‘How the Machine Affects Us’, in Foundations of Modern Art. New York: Dover Publications.

Severini, Gino. 1975. ‘Machinery’, trans. Tim Benton, in Architecture and Design, 1890-1939: An International Anthology of Original Articles, eds. Tim Benton, Charlotte Benton and Dennis Sharp. The Whitney Library of Design, New York.

British Patents list available with the British Library