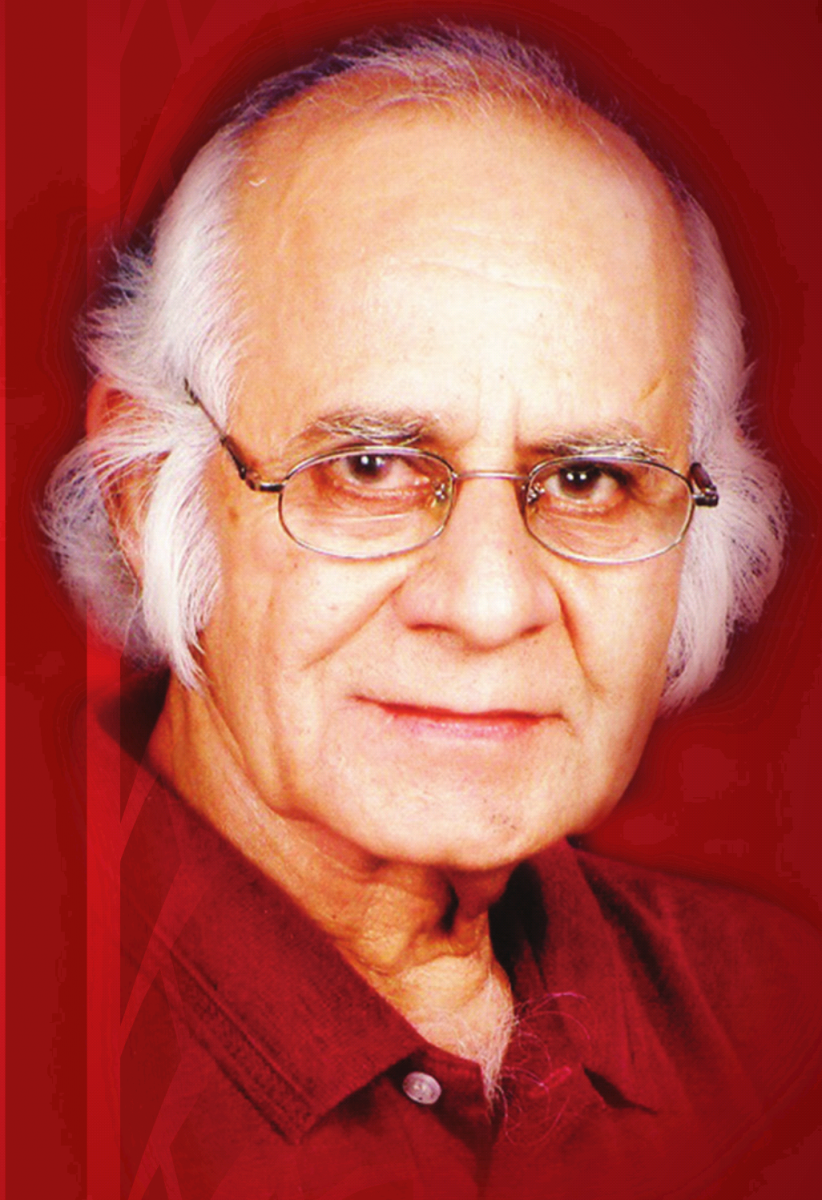

Vasdev Mohi (Vasdev Vensimal Sidhnani), one of the best-known contemporary Sindhi writers, was born on March 2, 1944, in Mirpur Khas, now in Pakistan. The Ahmedabad-based poet, critic and short story writer is the winner of numerous awards, including the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1999 for Barf Jo Thahyal (Made of Ice), which also won the Narayan Shyam Award. Among other awards, he has received the Sahitkar Sanman Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Council for Promotion of Sindhi Language and the A.J Uttam and Sundri Uttamchandani Lifetime Achievement Award; the Sindhi Sahitya Academy, Gujarat State Translation Prize for Antaral and the Lifetime Achievement Award of the Sindhi Academy, Delhi.

Mohi’s poetry collections include Tazaad (Contradictions, 1976), Subuh Kithe Aahe? (Where is Morn? 1983), Mankoo (poems related to a rustic character which were also translated into Gujarati and Hindi by Jaywant Relwani and Bhanwar Singh Panwar respectively, 1992), Barf Jo Thahyal (Made of Ice, also translated into English by Ram Daryani and Dr. Vinod Asudani, 1996), Chuhinb Mein Kakhu (Straw in the Beak, 2001) and Rail Ji Patri Meri (Dust on Rail Tracks, 2009).

His story collections are Chequebook (2012)—translated into Hindi as Daawat by Bhagwan Atlani, and into English as That One Moment by Dr Vinod Asudani (2015)—Chequebook and other stories in English, translated by Dr. Vinod Asudani (2016) and Dedh Gandh (One-and-a-Half Knots, 2016).

Mohi has also translated Tanizaki’s Japanese novel The Key as Sutal Atma… (1968) and other books from English and Hindi into the Sindhi language. His ghazals are available on cassette and CD, sung by Pawan Kumar and Ghanshyam Vaswani. His books Gaalh Shairee-a-Jee (Talk of Poetry) and Virhange Khanpoi Sindhi Ghazal Jo Handbook (Post-Independence Handbook of Sindhi Ghazal) are widely acclaimed.

Vasdev Mohi was Convener of the Sindhi Advisory Board, Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, for the period 2008–12. He was a lecturer and Head of Department (English) in the Indian High School, Dubai.

Menka Shivdasani: Tell us a little about your growing up, where you were born, and what were the Sindhi influences around you?

Vasdev Mohi: I was born in Mirpur Khas, Sindh, now in Pakistan, on March 2, 1944. After Partition, our family settled in Jodhpur. There was no atmosphere of Sindhi. After Jodhpur we came to Ahmedabad, where Sindhis lived in the locality. I got my education in Ahmedabad, first in Adarsh High School, then graduation from R.A. Bhavan’s College, and post-graduation from Gujarat University.

M.S.: Do you write in the Sindhi (Persio-Arabic script) or Devanagari script?

V.M.: I write in Persio-Arabic script.

M.S.: When and how did you decide to write poetry? What was your first poem about? How would you say you have developed as a poet in terms of themes and style?

V.M.: Writing poetry was not a decision, it just occurred. The first poem of most poets centres on love, mine was not an exception. Thereafter, my poems have encapsulated many themes—social, political, complex relationships with people around, love, etc. I write both metrical as well as non-metrical poetry. I am recognised both as a ghazal writer and also as a new wave poet.

M.S.: Was it a conscious decision to write in Sindhi?

V.M.: No, my mother tongue is Sindhi, I love my language, to write in it was/is a natural act.

M.S.: Did you ever feel that there might be a lack of readers for Sindhi poetry and if so, did it bother you?

V.M.: Poetry readers are fewer in other languages too, it does not bother me. I just unravel my inner self through poetry.

M.S.: Who were your mentors in pre-Partition days and which poets do you continue to read while living in India? What books and writers have influenced you?

V.M.: At the time of Partition I was a child. I have no mentors but I have learnt basics of prosody from the renowned Sindhi poet Arjan Hasid, who happens to be the maternal uncle of my wife Janki. I read scores of poets—Sindhi and also poets of other languages. I love writers and poets but I am not influenced by any.

M.S.: What themes do you generally focus on? Do you think Sindhi poetry has moved away from Partition-related themes?

V.M.: There are no fixed themes, but the milieu around me surely prompts me to write on it. Themes vary as per the need of the particular poem. The subconscious inner self is the repertoire of experiences, sometime Partition-related themes may emerge. But it’s true that other themes have taken over in mainstream Sindhi writings.

M.S.: Do you believe that there has been a resurgence in Sindhi culture in recent times, and if so, to what would you attribute this?

V.M.: Culture is not a piece of journalism that may be forgotten the next day. It runs in the veins of the community, it will remain with Sindhis for years to come. But the main part of culture—our language—definitely puts us in a state of worry. Sindhi education has almost waned; Sindhi-medium schools are converted to English-medium ones. Anyway, efforts to reverse the situation are on, hope something worthwhile will surely come up.

M.S.: What does the move towards Devanagiri to regenerate Sindhi mean for all the Sindhi literature of the past?

V.M.: Our concern here is that of language regeneration, script is not a problem. There is software which converts Persio-Arabic to Devanagri and vice-versa. There are many ways to convey yesteryear literature; audio books is one. There is digitising books to preserve old literature. The important thing is to keep our language alive in India.

M.S.: What do you foresee as the future for Sindhi poetry? Do you think efforts to regenerate the language are bearing fruit and that more youngsters are writing today?

V.M.: It’s heartening to note that young writers are coming up, some are very talented, and so we can hope for the best. But some areas are totally desert-like, wherefrom not a single young writer in the recent past has emerged on the scene, and those are such areas wherefrom we expect more writers to come up as there are many Sindhi colleges, e.g., Ulhasnagar and Ajmer.

M.S.: What would you say about the state of Sindhi fiction today?

V.M.: Novel-writing is not as we expect, but story writing is in full swing. Many stories can be put at par with global standards.