Introduction

The first Valmiki-Ramayana in Persian was one of the most celebrated manuscript projects of translation and illustration of any Hindu Sanskrit text, after Razmnama (The Book of Wars, the Persian translation of the Mahabharata) commissioned by Emperor Akbar (r.1556-1605), during his later regnal phase from 1580 to 1590 CE. This came after the illustrations of several series of Persian historical texts, tales and memoirs, including the enormous Hamzanama, the Tutinama and the Akbarnama.

The Ramayana of Akbar marked the development of a new stylistic genre in the Mughal courtly art under Akbar’s patronage.[1] The splendid illustrations of Akbar’s Ramayana are highly renowned for their acute naturalism, refined execution and the brilliance of surface treatment. A vivid and sophisticated colour palette and distinctive style defining the dynamic conflation of Indo-Persian aesthetic quality values represent the epitome of the classical Mughal idiom that developed during the Akbar period. A proclivity for the Persian classicism and Timurid aesthetic came by inheritance but the Indianised nature and character was foundational for the Mughal school of paintings.

This illustrated manuscript is a classic example of the assimilation of the indigenous culture and religious sentiments in the Mughal court and excellent workmanship of the artists of the royal atelier.The paintings reflect the extraordinary creative skills of the artists and their technical proficiency in deftly illustrating the narrative of Hindu origin in a different religious milieu by creating a coherent link between the text and the image. They represent visual interpretations of the varied emotive content, temporal spaces and moral dimensions of Rama’s mythology exuding a variety of metaphorical elements with symbolic values.

In Hinduism, the Ramayana is featured as a mythological epic that manifests the heroic exploits of Rama, glorifying and sanctifying him as an incarnation of the cosmic deity Vishnu, who descended on the earth in human manifestation to subjugate the demon king Ravana of Lanka. He was religiously ordained to accomplish the task of restoring the order or law (dharma) by his actions and removing ignorance by his valorous deeds, wisdom and virtuosity. Different versions of the text existed over time at various levels of the Hindu society, reflecting regional deviations, governed by distinctive conceptions rooted in the cultural and ideological contexts of local idioms. The text was originally compiled in the Kosala region from local oral traditions, during 500-300 BC, exemplifying the poetic tradition of ancient India. The emotional and spiritual depths displayed in the legend give an impression of valour, love, compassion, self-sacrifice, devotion to paternal authority and compassion for his subjects; ideating the ideal model of statecraft and portraying Rama as a universal monarch. The theme interested the Mughal emperor and his court.

In the Ain-i Akbari, Abu’l Fazl ibn Mubarak, Akbar’s biographer, ascribes the date of completion and names of the translators who carried out the project; according to which Mulla’ Abdul Qadir Badaoni was deputed by the emperor as the chief translator in partnership with Naqib Khan under the direction of a learned Hindu scholar, Deva Misra, who explained and summarised the Hindu text.[2] Badaoni, who was an orthodox Muslim, was disinclined to undertake the Persian translation of the Ramayana as noted in the Muntakhabu-t-Tawarikh.[3] Badaoni expressed his reluctance to participate in the translation of the Sanskrit texts and his fear of damnation. On the contrary, ‘Abu’l Fazl eulogised the Hindu texts, admirable didactic accounts of exemplary behavior, if not the exposition of religious truth’.[4]

The delicately rendered one hundred and seventy-six miniatures of the Ramayana were accomplished within just seven months after submission of its final translation by Badaoni on 28th Zulhijjia, 997 AH (November 6, 1589), consisting of three hundred and sixty-five finely calligraphed folios.[5] The illustration work started before the translation was complete, and most probably soon after the Razmnama was ready in 1586 or early 1587. However, John Seyller has proposed that one of the folios gives a date of the year AH 1000/AD 1591-92, indicating that the work was not completed for at least three years after the translation.[6] The imperial copy of the Ramayana is now in Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum in Jaipur.

Apart from the imperial manuscript, duplicate copies of the original text were prepared during Akbar’s period.The tradition of making multiple copies of the translated texts was popular during the Mughal period that developed to testify the importance of the manuscripts in the court. It is also noted by the scholars that there was one copy made in 1593 for Akbar’s mother, Hamida Banu Begum.[7] In addition, inspired by Akbar’s court art, Abdur Rahim Khan Khanan, the most powerful noble and the chief commander of Akbar's army, commissioned a personal copy of the Ramayana, prepared with the permission of the emperor.[8] Khananwas a poet and a great patron of arts and literature, who owned an individual kitabkhana and a painting workshop, composed of plenty of calligraphers, bookbinders, illuminators, and artists.[9] Based on an inscription given in the book itself, as well as the characteristic style of the illustrations, it has been surmised by scholars that this was not an imperial copy, but a sub-imperial copy of the Akbari manuscript.[10] According to the inscriptions written in the folios, the date of order by Abdur Rahim Khan Khanan is AH 996/ AD December 1587-November 1588 and the illustrations of the manuscript completed some six years after the given date.[11] The hundred and thirty extant illustrations of the sub-imperial Ramayana manuscript are now in the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington,which are remarkably congruent to the imperial copy.

During the same period, the Baburnama manuscript was also prepared by the same patron, who undertook the translation and illustrations of the text, written in Chagatai Turki, and presented to the emperor on its completion in 1589.[12] Besides, some of the loose folios of an incomplete Ramayana series, consisting of twenty-four paintings, dated to 1605 CE, were acquired by the National Museum, Delhi, Chhattrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai (formerly the Prince of Wales Museum of Western India) and Bharat Kala Bhavan, Varanasi as described by Pramod Chandra.[13]

The superbly illustrated imperial Ramayana manuscript gained remarkable prominence in the socio-political milieu too. The imagery depicted in this manuscript also acted as a visual metaphor of the religious tolerance and all-inclusive spiritual profundity practiced by Akbar. In addition, two more important Hindu sacred texts, including the Razmnama (The Book of Wars, the Persian translation of the Sanskrit epic the Mahabharata) and the Harivamsa (The Glory of Hari) were translated and illustrated during the same period.

This phase coincided with the political changes and religious reformations introduced by Akbar as described by Abu’l Fazl. By commissioning the Sanskrit manuscripts, Akbar founded a bedrock for his astute policy of political unification and socio-political reformation which he conceived with the foundation of the new and official belief system Din-ilahi (Divine Faith) and the establishment of the Ibadat Khana at Fatehpur Sikri, which was established as the capital for a brief period.[14] The foundation of Ibadat Khana (House of Worship) played a major role in peace-building by providing a uniquely noble and spiritual place for the appreciation and commingling of divergent philosophies, practices and ideas that were presented by invited scholars and adepts of diverse religious viewpoints who gathered and convened there. Pratapaditya Pal has noted ‘the practice of reading books in public must have had a salutary effect on his courtiers, both Muslim and Hindus, and contributed in no small measure to the renaissance of interest in painting in the country’.[15] This introduced a changed and liberal attitude of Islamic rulers towards the indigenous culture and traditions. Similarly, in the Mughal Ramayana, sage Valmiki was painted reciting the text to an audience, portraying the idea of benevolence and intellectual patronage.[16]

Apart from the emperor’s political interests, his strong inclination towards the seminal texts of Hinduism attests to his quest for knowledge of art and literature of divergent cultural backgrounds and his demanding taste for new themes. His marriage with the Rajput princess, Jodha Bai alias Mariam-uz-Zamani, evoked his poignant sensitivity and insatiable curiosity for Hindu culture and its religious literature. He recognised and appreciated the intellectual, edifying and ethical values imparted by the books and also admired the visuality of narrative art and illuminations illustrated in them. The writings of Abu’lFazl elucidate Akbar’s fondness and encouragement for painting.[17] According to the Akbarnama, Tarikh-i-Khandan-i Timuria, Tuzuk-I Jahangiri, Akbar learnt the art of painting under the supervision of two Persian masters, Abdus Samad and Mir Sayyid Ali, also attested by Abdus Samad’s miniature entitled ‘Akbar presenting a miniature to his father Humayun’ where Akbar is portrayed as a painter.[18]

As a great bibliophile and aesthete, Akbar brought together the indigenous artists, architects, poets, historians, painters and musicians. Masters artists from abroad too flocked to the Mughal court. He was deeply fond of art, discernible from a large number of illustrated manuscripts produced during his reign. The peregrinations of over one hundred talented artists from all over India of various racial, linguistic and religious groups and also from Western Asia, shows the immense popularity of Akbar’s atelier; they worked together on traditional and familiar subjects and mastered the Mughal style supervised by Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd as-Samad, producing sophisticated and high quality paintings displaying a uniform Mughal style.[19]

Akbar envisioned books and paintings not only as an efficient tool for dissemination of knowledge and spirituality but also as a medium of peace-building, promoting religious tolerance and harmony as well as, political and dynastic stability. By making the textual sources available to his subjects, Akbar displayed the belief that this would lead to the expansion of the consciousness of the Islamic population, social and communal gaps would be bridged between the people of different Orthodox communities and that, ethnic and sectarian conflicts and religious antagonism would be counterbalanced and eliminated simultaneously. It was with these aims and ideals in mind that the grand imperial mission of translation of many historical records of distinct languages and varied theological and philosophical contexts into Persian was undertaken and accomplished under his patronage, which led to a Mughal revolution in courtly art.

After Akbar’s demise, the imperial manuscript was dutifully passed down to his heir, emperor Jahangir, followed by his successors, as determined from the seals, inscriptions and dated notes, on the leaf. Interestingly, similar to other imperial illustrated manuscripts, like the Akbarnama, the Ramayana too has an autographed note by Jahangir on the opening folio, stating that it entered in kitabkhana in the first year of his reign, i.e. 1013 Hijri (1605), not only showing the tradition of inheritance but also Jahangir’s alacrity in becoming the successive owner of the newly acquired assets.[20]

The tradition of marking a seal or stamp as a mark of inheritance was common in the Mughal court, also seen in the case of the Ramayana manuscript. On its flyleaf, the date of completion of the text is noted and added, stating that it was viewed by Maryam Makani in August 1604, presumably when she was on her deathbed. This shows that the Ramayana held a significant position in the court and was not an ordinary manuscript. During Jahangir’s reign, two more translations of the Ramayana were prepared by Masihi Panipati and Girdhardas, counted among the literary masterpieces of the later period.Following the Mughal tradition, a famous set of Valmiki-Ramayana was commissioned by Rana Jagat Singh I of Mewar (r. 1628-1652), painted by Sahibidin, the famous miniature painter of the Mewar school, displaying a fine blend of the Mughal and Rajput styles.

Akbar’s Atelier: The Making of the Ramayana in the Mughal Court

Akbar inherited his great interest for collecting books and illustrated manuscripts from his father Humayun and his grandfather Babur; both were patrons and connoisseurs of Mughal art and literature, who continued to promote the past wonders of the Timurid tradition, even once they entered India. Akbar valued these precious books as the most prized possession of the royal treasury, which was not only celebrated as a collection of luxury and amusement items but also played an instrumental role in the spiritual development of the emperor and his subjects. To fulfill his profound urge to collect books and commission art, he consecrated the principal royal repository or library, called kitabkhana, as a part of his newly-built capital at Fatehpur Sikri. By the advent of the 1580s, the institution was firmly established and received large imperial benefactions for its refinement as the Mughal dynasty achieved a stronghold and political stability in India.

Similar to other Western Asian Islamic libraries of the early medieval period, the role of the kitabkhana was well-defined and structured in the Mughal period. The A’in-i-Akbari of Abu’lFazl describes the arrangement and activity of Akbar’s library which attained an exalted rank and became a symbol ofpolitical and dynastic power.[21] As an inveterate collector, Akbar acquired manuscripts through inheritance, conquest, purchase and gifts.[22] His imperial collection of books included Persian and Turkish manuscripts of the celebrated Timurid and Safavid dynasties from Herat and Bukhara, the non-Persian literary sources of other belief systems (mainly European and also Indianised), historical records, legends and tales, prints, albums of paintings and calligraphy and also unfinished manuscripts, which were completed under his supervision. This huge anthology of books and paintings, some of uncertain lineage and sources, were stored in the kitabkhana, where these books were not only cherished and studied by the emperor but also translated, illustrated and copied for the royal audiences.

New developments in Mughal paintings were encountered with the establishment of the kitabkhana at Fatehpur Sikri.[23] In addition to the preservation of manuscripts, the Mughal library constituted separate workshops (karkhanas) for carrying out several activities, including the translation and production of illustrated manuscripts, in which calligraphers, painters, artists, gilders, gold-mixers and bookbinders worked cooperatively as a centralised venture. Numerous artisans participated in these workshops and handled different tasks at various stages of manuscript preparation.

The configuration of Akbar’s kitabkhana and karkhanas was grounded on the Persian model as described by Abu’l Fazl and Anthony Monserrate, the Jesuit who visited the capital between 1580 and 1582 CE.[24] Hence, the Mughal taswirkhana (painting workshop) functioned as an indispensable unit of the kitabkhana, built in proximity to the imperial library as the execution of illustrations was dependent on the oral instructions dictated by the supervisor. The calligrapher too played a major role in orientation of the text and the intended image and; based on which instructions from both compositional formulas were devised by the individual artists. The painting workshop constituted several branches, where groups of artists were ascribed different activities based on their proficiency in particular fields, including- preparation of paper (sizing and burnishing), tarrahi (designing), chihra-kushai (portraiture), rang-amezi (colouring), manind-nigari (taking likeness), landscape drawing, flora and fauna studies, etc.[25]John Seyller has described the complex organization of the Mughal taswirkhana in which the task of manuscript production was assigned to various teams of painters, following a bi- or tripartite division of labour, where the sequence of activities and the putative visual programme were closely examined by the project supervisor, master artists, perhaps in consultation with the emperor himself.[26]

Immense attention was paid to ensure the smooth functioning of the painting workshop.Elaborate resources were allocated for obtaining and importing the supply of the finest of materials and commodities, such as paper, pigments, brushes etc., which gave painters an opportunity to expand their creative knowledge and produce desired outputs.[27] Besides, an inflow of huge financial grants brought stability to the royal atelier, since the artists were paid well and were conferred rewards according to the excellence of workmanship.[28] Inspired and encouraged by the Emperor, the artists attained an esteemed rank in the Mughal court.

With the growing efflorescence of the royal atelier, a large number of high-quality manuscripts were produced during the early 1580s. However, after the abandonment of Fatehpur Sikri, the aesthetic quality of the miniatures declined gradually leading to a major shift in the Mughal style, evidenced by the irregularities in artistic treatment and lack of refinement in illustrations of the later period. With the resettlement of the Mughal capital at Lahore, Akbar’s atelier too was shifted there. Asas a result, many experienced artists left the workshop, giving an opportunity to upcoming and amateur painters to join the atelier. Many such artists were consequently employed and took a part in this project.

The making ofthe Ramayana was one of the most extensive and unprecedented ventures of the Mughal atelier, which was conceived on an elaborate scale, engaging several artists from the taswirkhana, both of indigenous and Persian origin. In his account of Akbar’s painters, Abu’lFazl extensively described Akbar’s atelier, naming the leading artists and noting their contributions in the making of the Persian Ramayana manuscript.[29] Kesav, Lal, Baswan, Miskin and Mahesh are noted as the master artists, who made substantial contribution, assisted by a group of lesser-known artists, particularly hailing from Western and Central India.

The artists produced a varied number of compositions and their works became recognised by their characteristic stylistic rendition as each specialised or excelled in a particular skill or an aspect of painting, such as- designing, colouring, illuminations and so ons. The artists from the royal atelier involved in this project, included- Lal and Keshav, who executed a bulk of the compositions, making thirty-seven and thirty-six paintings respectively; while Basawan and Miskin created fourteen each; Jagan produced thirteen and Mahesh eight. Besides, Mando or Mandu was another artist from Akbar’s workshop, associated only with the Ramayana project and credited for the creation of eight miniatures; while other artists were Bhagwan and Mukund. The configuration of Abd Al-Rahim’s atelier was vastly different, in which a single artist was assigned one illustration only, surmised from the seventy-seven ascriptions and four actual signatures in the folios. Thirteen painters have been recognised as having worked for the sub-imperial Ramayana project, namely,-Fazl, Ghulam Ali, Govardhan, Kala Pahara, Kamal, Mohana, Mushfiq, Nadim, Nadir (Bihbud), Qasim, Shyama Sundara, Yusuf Ali and Zayn al-Abidin.[30]

Discussion on Imperial and Sub-Imperial Styles of the Ramayana Manuscripts

The original Sanskrit Valmiki-Ramayana is a compendium of twenty-four thousand verses, compiled in seven books, in which books two to six deals with varied narrative portions, focusing on Ayodhya and episodes from Rama’s life, while book one and seven were later additions, known as Adi and Uttara Kanda. The main story begins with book two, titled ‘Ayodhya’ narrating the lineage of the royal house of Ayodhya and the courtly affairs centering on King Dasaratha and his four sons- Rama, Bharata, Lakshmana and Shatrughana as well his three wives; marriage of Rama to Sita, the daughter of King Janaka of Videha; the succession of Bharata on the throne; Dasharatha’s demise and the exile of Rama with Sita and Lakshmana to the forest; while the remaining books, titled Aranya (the forest), Kishkinda (the kingdom of the monkeys), Sundara (the beautiful), and the Yuddha (the war) Kanda represent events and characters related to Rama’s exploits in Dandaka forest, the abduction of Sita by Ravana, Rama’s campaign to rescue his wife, culminating in the attack on Ravana’s abode, the island of Lanka, and ultimately his annihilation.

In the imperial Ramayana manuscript from Jaipur Museum, the story is illustrated in the form of thirteen double page compositions, depicting episodes particularly from the first two books and the last two, yet showing inconsistency in some sections mainly seen in the selection of themes by the artists. Following the same pattern, Abd al-Rahim Khan’s artists also developed the sub-imperial copy of the text, in which design of the painting cycle and also the basic conceptual framework of individual illustrations were derived from the imperial version. John Seyller states that the Jaipur manuscript was used as a standardised format for the Freer Ramayana, therefore both the copies share strong semblances,as seen from the similar kind of narrative pattern and selection of themes for illustrations.

Yet, differences between the two versions can also be traced, such as in the Freer manuscript, the illustrations appear pictorially simplified and;lesser vibrant, but more emphasis is laid on visual design. Further they display an affinity for indigenous style, witnessed from the costumes and attire of the characters and also architectural elements.Also, the Freer manuscript illustrations strictly conform to the textual description more precisely than the Jaipur manuscript, however, in the former iconographic inconsistencies are visible. According to Pratapaditya Pal, the Freer Ramayana’s colour palette is subdued and dull, lacks dimensionality due to its simplistic perspective and monotonous compositional elements, and the figures are treated like cut-out images, static in nature, lacking coordination with the background elements and landscapes.[31]

Taking into consideration the Hindu iconography and textual prescriptions, the Mughal painters systemised a fixed iconographic schema for the representation of the protagonists and the Hindu deities with their attributes,in which standard features were presented, but characterization and appearance of each divinity altered sporadically based on the changing circumstances following the narrative order. In this regard, John Seyller opines that the artists of both the Jaipur and Freer Sackler Ramayana developed a consolidated iconography to overlook the challenge and problems of misidentification, but the major forms are represented in their most characteristic form.

The characteristic features are as follows- Rama and Lakshmana are shown as warriors weilding bows, wearing typical indigenous male costumes,- an unstitched cloth wrapped as a lower garment (dhoti) and a sash covering the upper body and adorned by crowns topped with flowers; Sita is bedecked in Rajasthani-styled short blouse (choli) and a diaphanous long skirt (ghagra); Indra, Brahma, Shiva, Vishnu and other Hindu deities are characterised by their attributes and mounts; and Hanuman is recognised by his distinct physiognomy, attired in princely costumes and crown. Unlike the Hindu deities, the courtiers or passive onlookers in the scenes, which are mostly male, are clad in the Mughal attire of Akbari period:- a long coat or dress with a round skirt to be tied on the right side, paired with tight-fitting trousers and a colourful sash holding the dagger (called as the chakdharjama) and a turban. This type of male costume was an invention of Akbar’s couture, which is a byproduct of the Mughal rulers’ interest in fashion and ornamental textiles as they always had a deep interest for experimenting with new clothing styles.

To understand this iconographic schema, by considering one of the Jaipur Museum folios, illustrating ‘Nishada King Guha’s meeting with Rama, Sita and Lakshman’, designed by Mukund and coloured by Bhagwan, it can be seen that the protagonist and his companions are depicted in sagely demeanor, bereft of royal regalia, yet are identifiable by the standard iconographic features as discussed above.[32] However, the king and his courtiers are decked in Mughal styled costumes and head gears. This painting depicts an episode from the Ayodhya Kanda, in which Rama after bidding farewell to his birthplace Ayodhya, reaches the banks of the holy Ganga where the Nishada king offers a reception to Rama, Sita and Lakshmana.

The artist follows the textual description, according to which the exiled prince takes a seat beneath a fig tree to accept gifts from the tribal king. The king accompanied by his retinue and charioteer are shown gathered to pay obeisance to Rama, Sita and Lakshamana. Here the dense forest and wilderness are well-portrayed by the depiction of variety of flora and fauna, while the city of Ayodhya, suggested by architectural establishments, is seen in the background, suggestive of the changing temporal space and narrative progression. The same scene is illustrated in the Freer Sackler manuscript also, but differences in style and iconographic formations are identifiable, for example, the protagonists are decked in royal attire and Sita is omitted from the scene. Furthermore, the Hindu deities, Shiva, Brahma, Vishnu and Indra are shown witnessing the event and the river is prominently depicted, none of which are present in the Jaipur manuscript.

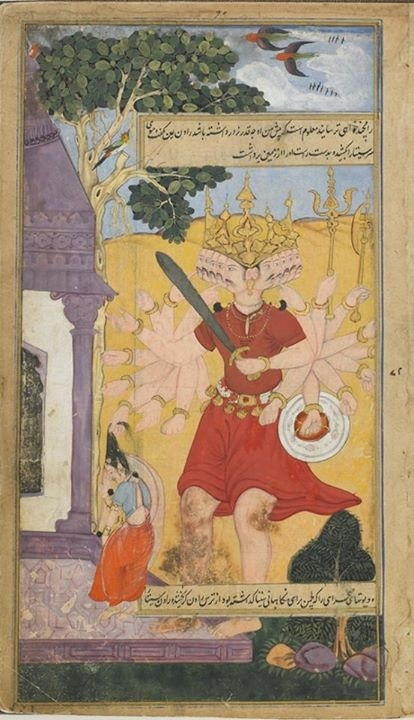

Sita, the consort of Rama and incarnation of goddess Lakshmi, is one of the central female figures of the epic, exemplifying the virtues of an ideal woman and wife. The character of Sita is dealt sensitively by the Mughal artists, depending on the portrayal of a specific episode, showing different shades of her nature. She is depicted as being exceptionally loyal following her husband into exile, while being vain and willful, which led to her kidnapping by Ravana and also in a compassionate and self-sacrificial state. For example, in the scene depicting the ‘Abduction of Sita by Ravana’[33] from the Freer Sackler collection (pl.1), the giant figure of the multi-armed and multi-headed Ravana occupies a central space, while the figure of Sita, shown captured by the demon, is rendered in a miniscule size, expressing her feeble and humiliated state. The barren lands in the background coloured in yellow, is suggestive of melancholia and remorse. The subsidiary elements in the background act complementary to the central figures as denoted by the seasonal changes, flora and architectural setting.

Fig. 1: Ravana seizes Sita by the hair to abduct her to Lanka

In another painting, ‘Sita shies away from Hanuman, believing he is Ravana in disguise’[34], from the Jaipur Museum collection (pl.2), Sita is seen captive in one of Ravana’s palaces where Hanuman discovers her as he was sent by Rama to find her. Here, Sita is shown as being timid and fearful during her encounter with Hanuman, but after realising the truth, she gifts Hanuman her ornament and asks him to deliver it to her husband as a remembrance. After this, Hanuman returns across the sea to Rama. In this painting, the artist has given special attention to the rendition of Mughal architecture, evidenced from the intricate pietra dura work and the hexagonal-styled char-bagh plan, which are the dominant features. In addition, the physiognomy of Sita also shows an influence of Persian style; and she is dressed in a gossamer blouse and a billowing skirt with her hair tied in a bun and tresses falling on her shoulder, while Hanuman decked in royal attire appears to be paying obeisance to Sita. The colour palette is vibrant and the artistic treatment shows great emphasis on intricacy and detailing.

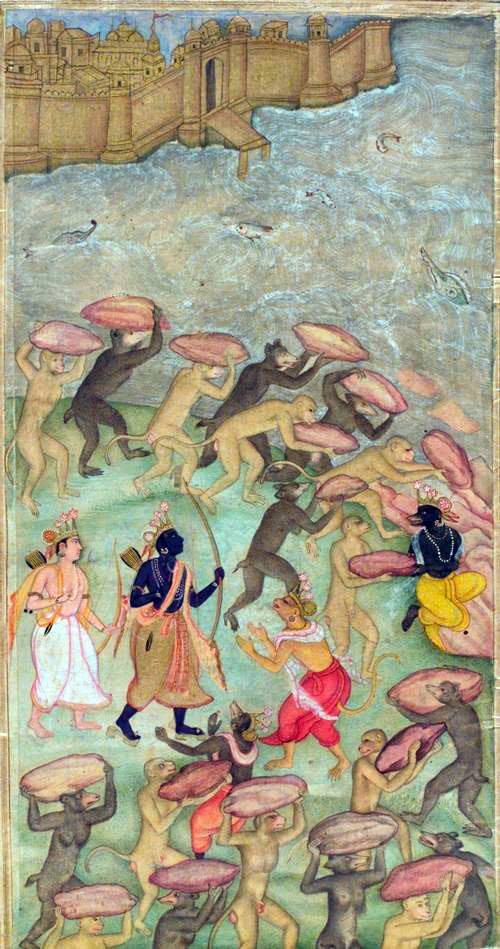

Apart from this, in the Jaipur Ramayana a majority of the compositional area customarily depicts the main episode, surrounded by paraphernalia, like architectural establishments and flora and fauna features that occupy the foreground and background spaces. These additional elements are indicative of the topological variations, emotive qualities and spatial schemes. At times, the background is shown overtly crowded with human figures, denoting a sense of urgency and chaos, yet projecting a strong sense of naturalism but with exaggerated physical and emotional activity therein. This can be observed by taking an example of one the compositions showing ‘Nala and army of monkeys helping Rama build a bridge’(pl.3). Astrong sense of naturalism and momentum exude the painting, conveyed by the dynamic gesticulations of the army of moneys (vanaras), who are shown transferring the boulders and helping Rama to construct a bridge across the ocean, connecting to the kingdom of Ravana. [35]The monkey army was supervised by Nala, the chief engineer and son of Vishwakarma, and his brother Nila, also in royal attire, both depicted in blue and yellow complexion respectively. They volunteered to help Rama in the creation of the bridge. Swirling motions of the ocean waves and the aquatic life add liveliness to this image.

Fig. 2: Nala and army of monkeys helping Rama build a bridge

Another folio that can be used as an example from the Jaipur Museum is ‘Hanuman snatching away Ravana’s golden crown’, designed by Jagan and coloured by Sarwan, from the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust, Jaipur.[36] Here the demon king Ravana is shown reclining on his couch inside a pavilion, surrounded by a large number of composite figures denoting his demon army, shown in a hustle, while the mischievous Hanuman depicted in the background is shown fleeing with Ravana’s golden crown. Ravana is featured in his humongous physical characteristics, endowed with ten heads and twenty arms, decked in royal attire, while the demons look grotesque, wielding weapons and depicted with spots, horns and clad in short skirts, which are Persianised features. Here, the sense of turmoil and conflict dominates the scene and the composition appears overtly crowded. The architectonics and decoration of the pavilion follow the typical Timurid and Mughal style, such as the intricately designed tile-work with floral scrolls and geometrical patterns, adorning the domical structures, walls and the floor as well. To suggest the palatial setting, the foreground is demarcated with fortification walls and bastions.

In another folio from the same collection, illustrating ‘Bharata and Shatrughna bid farewell to Dasharatha before proceeding to Kekaya with Yudhajit’, the architectural rendition and components act as tools to define perspective and narrative order and are also used for ornamentation.[37] But here the architectonics show an admixture of indigenous and Mughal styles. The king Dasharatha and the princes, and other male courtiers are clad in typical Akbari styled costumes, differentiated by a variety of headgear and attributes. The foreground is filled with jubilant female dancers, male singers and musicians playing the drums, trumpets and stringed instruments, celebrating the event, while the charioteer and courtier, standing at the gateway, are suggestive of the embarkment of the journey.

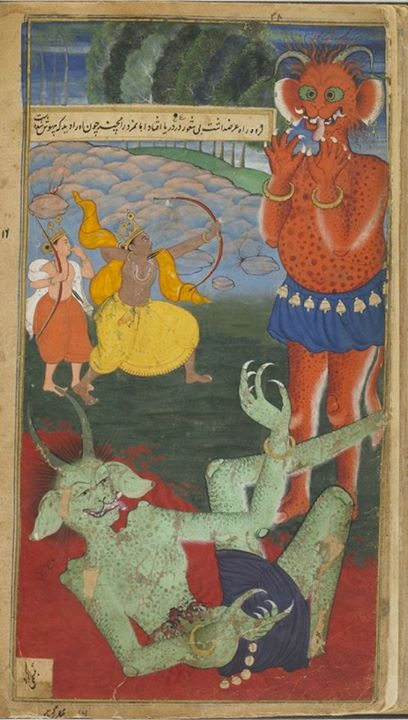

The Freer Sackler Ramayana illustrations follow a similar pattern of usage of background elements, but the protagonists dominate the scenes, making the identification of the scenes easier for the reader.For example, in the folio showing ‘Rama and Lakshmana confront the demons Marica and Subahu’, the figures of Rama and Lakshmana slaying the gigantic demons Marica and Subahu are portrayed as the main elements of the composition, while the background appears dull and painted in subdued shades(pl.4).[38]

Fig. 3: Rama and Laksmana confront the demons Marica and Subahu

In addition to the stylistic features, certain mythic metaphorical narrative elements were also introduced in the images, derived from Persianised culture. Gregory Minissale has interpreted the metaphorical visual elements and their implications in the Mughal compositions based on literary references. Some of the components discussed by him are identified in the Ramayana folios of both the Jaipur and Freer Sackler collections. For example,the cave appearing almost as a peripheral element consistently in the background, represents a place where people seek refuge or receive initiation, wisdom or revelation; similarly, the water pot infers the idea of life; the use of animal motifs by the Mughal rulers are a part of their image of kinship; and thefire is a symbolic motif with a multitude of meanings, it is a symbol of truth and also a calamitous self-immolation or cataclysmic fire destroying the whole cosmic cycle.[39] Fire is treated as a symbolic motif which has both a destructive and cleansing force, while the cave signifies esoteric wisdom.[40]

There are many scenes from the Ramayana depicted in the illustrations which emphasise this visual element. For example, in the Freer Sackler folio depicting ‘Indra preventing King Trisanku in physical form from ascending to heaven’ the sacred fire altar dominates the scene, unfolding the idea of redemption of the King Trisanku alias Satyavartha, one of the ancestors of Rama, from the curse of sage Vashistha. This story is narrated in the Bala Kanda of the Valmiki Ramayana.[41]As pointed earlier, this painting shows an amalgamation of indigenous and Persianised elements, identified by the male figures who are dressed in Indian attire, while background elements, such as the rocky terrain and the undulating clouds and the diffused colour tones bespeak of Persian influences.

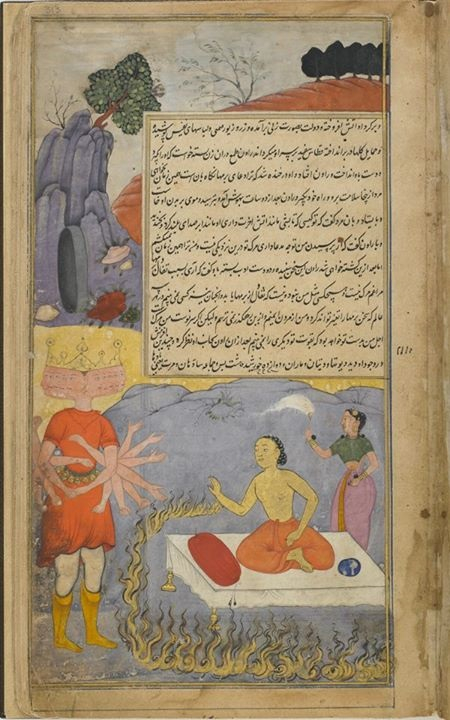

In another folio ‘Ravana converses with Mahajambunada, who is surrounded by a ring of fire and attended by Lakshmi’[42]from the Freer Sackler collection (pl.5), the fire element is emphasised through the narrative outline and compositional elements. Gregory Minissale has interpreted this representation as a visual metaphor, comparing the event with the episode of Jesuit debate with the Mullahs, as recorded by Father Monserrate at Akbar’s court when a trial by fire was discussed as a way to resolve conflict.[43]Similarly, the same element appeared in the Jaipur Museum Ramayana manuscript, depicting the ‘Emergence of Agni-purusha from the Pyre’, designed by Basawan and coloured by Husain Naqqash.

Fig. 4: Ravana converses with Mahajambunada, who is surrounded by a ring of fire and attended by Laksmi

The iconographic elements, aesthetic quality and stylistic delineations discussed above remain uniform yet variedly represented in the imperial and sub-imperial manuscript illustrations based on the narrative order and the selection of theme. The story of the Ramayana became immortalised in Persian literature through the illustrations commissioned by Akbar. The great interest in paintings exhibited by Akbar left a lasting impression on the Mughal tradition, which was inherited by his successors. Mughal literature and art proliferated in the following periods and influenced the artistic developments of different regional schools of art during the high medieval period.

Note

[1]Asok Kumar Das, ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript.’ In Vidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 84.

[2]Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 86.

[3]Ibid., 85.

[4]John Seyller. ‘A Sub-Imperial Mughal Manuscript: The Ramayana of Abd Al-Rahim Khan Khanan.’In Vidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 86.

[5]Asok Kumar Das, ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript.’ In Vidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 74.

[6]John Seyller. “A Sub-Imperial Mughal Manuscript: The Ramayana of Abd Al-Rahim Khan Khanan”. In Vidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 87.

[7]Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 85.

[8]In 1907 Charles Lang Freer bought the collection of Indian paintings that belonged to Colonel Henry Bathurst Hanna, which included a Mughal manuscript of the Ramayana. (See: Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 85.

[9]Asok Kumar Das. ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript’ InVidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 74.

[10]Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 87.

[11]John Seyller. ‘A Sub-Imperial Mughal Manuscript: The Ramayana of Abd Al-Rahim Khan Khanan’. In Vidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 88.

[12]Pratapaditya Pal, Court Paintings of India: 16th-19th Centuries (New York: Navin Kumar, 1983), 34.

[13]Pramod Chandra. A series of Ramayana of the Popular Mughal School. Princes of Wales Museum Bulletin, No.6, (1957-59), 64-70.

[14]Milo Cleveland Beach, Early Mughal Painting (Cambridge, Mass. U.: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1987), 83.

[15]Pratapaditya Pal, Court Paintings of India: 16th-19th Centuries (New York: Navin Kumar, 1983),34-35.

[16] Gregory Minissale. Images of Thought: Visuality in Islamic India 1550-1750. (UK: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006), 147.

[17]The description runs as follows:- ‘The pictures thus received a hitherto unknown finish. Most excellent painters are now to be found, and masterpieces worthy of Bihzad may be placed at the side of the wonderful works of the European painters who have attained worldwide fame. The minuteness in detail, the general finish, the bold of execution, etc., now observed in pictures, are incomparable, even inanimate objects look as if they had life. More than a hundred painters have become famous masters of the art whilst the number of those who approach perfection, or those who are middling is very large’. (See: Asok Kumar Srivastava, Mughal Paintings: An Interplay of Indigenous and Foreign Traditions (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2000), 22.)

[18]Asok Kumar Srivastava, Mughal Paintings: An Interplay of Indigenous and Foreign Traditions (Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2000), 20.

[19]Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 24.

[20]Susan Stronge, Painting for the Mughal Emperor: The Art of the Book 1560-1660 (Delhi: Timeless Books, 2002), 54-55

[21] The A’in-i-Akbari description runs as follow: ‘His Majesty’s library is divided into several parts; some of the books are kept within, and some without the Harem. Each part of the library is sub-divided, according to the value of the books and the estimation in which the sciences are held of which the book treat. Prose books, poetical works, Hindi, Persian, Greek, Kashmirian, and Arabic are all separately placed. In this order they are also inspected’. (See: Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 10-11.)

[22] Michael Brand and Glenn D. Lowry, Akbars India: Art from the Mughal City of Victory (New York: Asia Society Galleries, 1986), 107.

[23] Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 11.

[24]Bernier’s observation of the constitution of the karkhanas under Aurangzeb in the seventeenth century, provides an idea of the Akbar’s karkhana. Similar type of royal workshops continued to exist even during the last days of the Mughal dynasty. Bernier explained: Large halls are seen in many places, called Kar-kanays or workshops for artisans. In one hall embroiderers are busily employed, supervised by a master. In another you see the goldsmiths; in a third, painters; in a fourth, varnishers in lacquer work; in fifth, joiners, turners, tailors, and shoemakers, in a sixth, manufactures of silk, brocade, and those fine muslins of which made turbans, girdles with golden flowers and drawers won by females, so delicately fine as frequently to wear out in one night (See: Pratapaditya Pal, Court Paintings of India: 16th-19th Centuries (New York: Navin Kumar, 1983), 13.)

[25]Asok Kumar Das. ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript’, InVidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 74.

[26]John Seyller. ‘Painting Workshops in Mughal India’, In Karkhana: A Contemporary Collaboration.(Ridgefield, CT/London: The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum and Green Cardamom, 2005), 12–17.

[27]Milo C. Beach, The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012), 13.

[28]Mohinder Singh. Randhawa and John Kenneth Galbraith, Indian Painting; the Scenes, Themes and Legends. (Calcutta: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., 1968), 26.

[29]Asok Kumar Das. ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript’, 76.

[30]John Seyller. “A Sub-Imperial Mughal Manuscript: The Ramayana of Abd Al-Rahim Khan Khanan”. In Vidya Dehejia, ed., The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions (Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994), 91-92.

[31]Pratapaditya Pal, Court Paintings of India: 16th-19th Centuries (New York: Navin Kumar, 1983), 30. Milo C. Beach also refers to the term ‘sub-imperial’ since this manuscript commissioned by a Mughal noble rather than by the Emperor or members of his immediate family.

[32]Asok Kumar Das, ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript’, pl.7, 81.

[33]Abduction of Sita, Folio from the Ramayana of Valmiki (The Freer Ramayana), Vol. 1, recto: text; verso,Ghulam 'Ali,1597-1605 (Indian, Mughal dynasty Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper H: 27.1 W: 14.3 cm Northern India F1907.271.57, https://www.si.edu/object/fsg_F1907.271.1-172 (Courtesy: Rare Book Society of India, http://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/postDetail.php?id=196174216674_10151910781716675)

[34]‘Sita Shies Away from Hanuman, Believing He is Ravana in Disguise’, Miniature from a copy of the Ramayana.India, Mughal; 1594, Leaf: 37.8 × 25.6 cm, (Courtesy: Rare Book Society of India, https://www.facebook.com/196174216674/photos/a.212955701674.174468.196174216674/10152799149786675/?type=1&theater)

[35](Courtesy: Rare Book Society of India, http://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/postDetail.php?id=196174216674_10152799141721675;

[36]Asok Kumar Das, ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript’, pl.8, 81.

[37]Ibid., pl.6, 80.

[38]Folio from the Ramayana of Valmiki (The Freer Ramayana), Vol. 1, folio 38; recto: text; verso: Rama and Laksmana Confront the Demons Marica and Subahu, 1597-1605, By Mohan, India, Mughal dynasty Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, H: 26.1 W: 13.9 cm, Acc. No. F1907.271.57,Courtesy: Rare Book Society of India,http://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/postDetail.php?id=196174216674_10151914772156675)

[39]Gregory Minissale. Images of Thought: Visuality in Islamic India 1550-1750. UK: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006, 160-174.

[40]Ibid., 164.

[41]According to the story, King Trisanku approached sage Vashistha to perform needful rites to ascend him to the heaven in the physical form, but after being refused by the sage since his wish was against the law of nature, Trisanku attempted to convince the sage’s son to help him and positioned him as his father’s rival, which enraged the sage and he cursed Trisanku and turned him into a horrific form, forcing him to leave the country and wander the forests. Trisanku met Vishwamitra during his wanderings and beseeched him for help. Vishwamitra used his powers and conducted the rituals, attempting to send the King to the heaven, but being opposed by Indra and the Devas, as this was an unnatural act, Vishwamitra created a new heaven named after the King where he could reside in his restored form (See: Folio from the Ramayana of Valmiki (The Freer Ramayana), Vol. 1, folio 57; recto: text; verso: Indra prevents Trisanku from ascending to Heaven in physical form 1597-1605 Ghulam 'Ali , India, Mughal dynasty Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper, H: 27.1 W: 14.3 cm , F1907.271.57, (Courtesy: Rare Book Society of India, http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/zoomObject.cfm?ObjectId=50284)

[42]The story runs: ‘Having conferred this boon upon Ravana the grand-father, sprung from lotus, speedily returned to the region of Brahman. And having obtained the boon Ravana too came back. After a few days that Rakshasa Ravana, the dread of all people, arrived at the banks of the western Ocean with his councillors. And on the island a person was seen bright as fire under the name of Mahajambunada, seated there alone. He had a dreadful figure and was like unto the fire at dissolution. And beholding that highly powerful person amongst men like unto the chief of gods amongst the celestials, the moon amongst the planets, the lion amongst the Sarabhas, the Airavata amongst the elephants, the Meru amongst the mountaIns, and the Parijata amongst the trees, the ten-necked demon said "Give me battle." There at his eyes became agitated like unto planets and from the clashing of his teeth. A fabulous animal supposed to have eight legs." (See: Ravana converses with Mahajambunada, who is surrounded by a ring of fire and attended by Laksmi, Folio from the Ramayana of Valmiki (The Freer Ramayana), Vol. 2, folio 313; recto 1597-1605, Painted by Kamal, (Courtesy: Rare Book Society of India, http://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/postDetail.php?id=196174216674_10151910783786675, https://www.si.edu/object/fsg_F1907.271.1-172; ))

[43]Gregory Minissale. Images of Thought: Visuality in Islamic India 1550-1750. UK: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006, 164.

Bibliography

Beach, Milo C. Early Mughal Painting.Cambridge, Mass. U.: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1987.

Brand Michael, Glenn D. Lowry. Akbars India: Art from the Mughal City of Victory. New York: Asia Society Galleries, 1986.

Chandra, Pramod. A Series of Ramayana of the Popular Mughal School. Princes of Wales Museum Bulletin, No.6, (1957-59), 64-70.

___. The Imperial Image: Paintings for the Mughal Court. Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2012.

Das, Asok Kumar. ‘Akbar’s Imperial Ramayana: A Mughal Persian Manuscript.’ In Vidya Dehejia, edited by. The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions. Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994.

Minissale, Gregory. Images of Thought: Visuality in Islamic India 1550-1750. UK: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2006.

Pal, Pratapaditya. Court Paintings of India: 16th-19th Centuries. New York: Navin Kumar, 1983.

Randhawa, Mohinder Singh, John Kenneth Galbraith. Indian Painting; the Scenes, Themes and Legends. Calcutta: Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., 1968.

Seyller, John. ‘A Sub-Imperial Mughal Manuscript: The Ramayana of Abd Al-Rahim Khan Khanan.’ In Vidya Dehejia, edited by. The Legend of Rama: Artistic Visions. Bombay: Marg Publications, 1994.

Srivastava, Asok Kumar. Mughal Paintings: An Interplay of Indigenous and Foreign Traditions. Delhi: MunshiramManoharlal Publishers, 2000.

Stronge, Susan. Painting for the Mughal Emperor: The Art of the Book 1560-1660.Delhi: Timeless Books, 2002.