Pahari painting is a style of miniature painting that, falls under the larger spectrum of Rajput paintings – a style which encompasses many different schools that evolved under the benefaction of the Rajput rulers of Northern India from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. The term Rajput painting was coined by Ananda K. Coomaraswamy in order to differentiate this painting style from that of the Mughal court.[1]The Pahari Schools comprise of the paintings of the Rajput Hill states.

This region, now known as Himachal Pradesh, was until the late 1940s known as the region of the Punjab Hills.[2] It was established as a province constituting thirty princely states,[3] set up by Rajput princes from the plains.[4] The region went through many modifications in size and administrative systems from this point on. In 1966 many of the Punjab hill areas, that included Shimla, Kangra and Kullu, were absorbed into Himachal Pradesh along with the predominantly Buddhist district of Lahaul and Spiti and others. Some of the prominent parts of this region like Basholi and Jammu were absorbed by the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In 1971, Himachal Pradesh became the eighteenth state of India.[5]

Though the evolution of Pahari miniature paintings occurred a little later than that of Rajasthani miniature paintings, they produced thousands of illustrations which are scattered across various collections all over the world. They are extraordinary in their themes that visually represent the verses of Hindu literary texts, giving us a glimpse of medieval culture. They portray heroes (nayakas) and heroines (nayikas) and convey the spirit of the classical tradition of rasas that existed in painting, poetry, literature and dance.

The paintings are executed on handmade paper and carry within them various tradition of miniature art which include Jain manuscripts, Chaurapanchasika (an illustrated Sanksrit love epic), western Indian style of painting, medieval style influenced by Islamic traditions along with the rich and vigorous folk style of painting that existed in the hill regions. The important Pahari schools identified on the basis of their regional affiliation are Basholi, Guler and Kangra. The lesser schools include Chamba, Mandi, Kullu, Bilaspur, Garhwal, Jammu, Nalagarh, Kashmir and Dharamshala.[6]

One of the favourite themes of Pahari paintings was the illustration of the epic Ramayana, which tells the story of Rama, a warrior prince.[7] Having been passed on through the oral tradition for centuries, the Ramayana was first written down in Sanskrit by the poet Valmiki around 300 BCE. The epic contains 2400 couplets that are woven with mythology and legend.[8] The narratives of the Ramayana contain moral lessons that are told through a series of events combining adventure with magical occurrences. They tell us of the love between Rama and his wife Sita and that helped them overcome enormous odds in order to reunite with each other.

As per the narrative, Rama, the crown prince of Ayodhya, was exiled from his kingdom for fourteen years due to court conspiracy. His loyal step-brother Lakshmana decided to accompany him to the forest as did his wife Sita (despite strong opposition). In the last year of their exile, Sita was kidnapped by Ravana, the king of Lanka, who was besotted by her. The account continues to describe Rama’s despair and his struggle to locate Sita, the forming of his alliance with the vanaras[9], his siege of Lanka, the killing of Ravana after a long and arduous battle and their return to Ayodhya. It also talks about Sita’s defiant opposition to Ravana’s advances while she was imprisoned for a year in the Ashoka Vatika. The epic talks of honour, loyalty, duty, valour, devotion, betrayal and most importantly, the victory of good over evil. The Ramayana, considered to be one of the world’s greatest epics by many, is a favourite for recitation and enactment during important Hindu festivals (particularly Dussehra).

This article will review the paintings that are visual representations of the anecdotes from the Ramayana, as seen in the paintings of the hill states of India. The article aims to carry out a stylistic and comparative study of these paintings while hoping to bring out the unique way in which these tales have been illustrated in the Pahari style, keeping in mind the compositions, topographical representations, the appearance of the protagonists and other methods of illustration used by various Pahari schools.

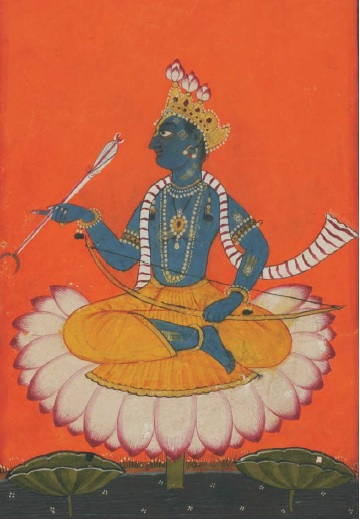

Basholi is the earliest of the Pahari schools to have been developed. It grew under the patronage of Raja Kirpal Pal (r. 1678 – 1693 CE) and took inspiration from local painting traditions, possibly the practice of painting wooden furniture as a means of ornamentation. It gave impetus to many Pahari Schools in the early period. This ‘Portrait of Rama’ (Plate 1: Ramayana in Indian Miniatures, National Museum Exhibition), is a characteristic example from Basholi, which is known for its brilliant hot colours, backgrounds devoid of perspective and schematic tree forms. In the portrait, Rama is shown seated on a stylised lotus, emerging out of a pond that contains dark, still water. Two lotus leaves emerge from the gentle rhythmic waves of the water, to frame the base of the painting providing balance and symmetry.

Fig. 1: Portrait of Rama. Basholi style, Pahari, Early eighteenth century. Paper, 14.8 cm x 10.2 cm Acc. No. 61.1000 http://www.nationalmuseumindia.gov.in/pdfs/Ramayan-in-Indian-Miniatures.pdf

Basholi created a typical facial formula for its human figures that can be seen in the features of Rama, in the fish shaped eyes, receding forehead and heavy set face. He is represented as blue in colour and wears a saffron dhoti to highlight his identity as the incarnation of Lord Vishnu. He holds a bow in his left hand and an arrow, with a crescent tip (possibly the Brahmastra)[10] in his right hand. He is heavily adorned with gold jewelry. The crown with the three lotus buds is a typical feature of Basholi art.

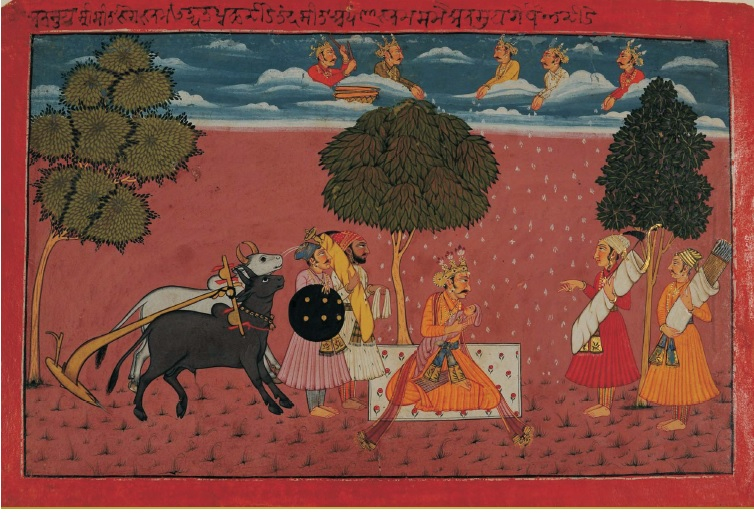

The next two paintings from Mandi, reveal an influence of the Basholi School and a tie with folk traditions. The Mughal court of Aurangzeb also exerted an influence on Basholi and other early schools of the hill regions, which is seen mainly in the costumes and the architecture represented. The first painting (Plate 2: Ramayana in Indian Miniatures, National Museum Exhibition) depicts the moment when king Janaka[11] discovered the infant Sita, while ploughing the field, during an annual harvesting ritual he was required to carry out as part of his kingly duties. He is seated in the center of the composition on a carpet, flanked by standing male figures, that tower over him on either side while holding weapons. Taking inspiration from the comparatively egalitarian culture of the hill regions, Pahari miniature paintings are not as concerned with depicting a rigid hierarchy as seen in the Rajasthani miniatures. This representation is an example of the breakdown of hierarchy; a king would never be depicted seated in a subsidiary position to his attendants, or on the ground in Rajasthani miniatures. They are all dressed in jamas, influenced by the Mughal court.

Plate 2: King Janaka Discovers Infant Sita when Ploughing the Land. A folio from the Shangri Ramayana Mandi style, Pahari Mid-eighteenth century, Paper, 21 x 31.2 cm Acc. No. 62.2521. http://www.nationalmuseumindia.gov.in/pdfs/Ramayan-in-Indian-Miniatures.pdf

The ground beneath him is depicted in a dull red colour, a pair of bullocks bearing a plough stand towards the left as a reminder to the occasion. Three highly stylised trees behind Janaka, introduce the viewer to variety in the local vegetation. The blue sky above is filled with clouds reminiscent of repetitive, frothing waves. Male celestial figures protrude out of the clouds to shower Janaka with flowers and play celebratory drums.

The second painting from Mandi (Plate 3: Ramayana in Indian Miniatures, National Museum Exhibition) depicts the marriage of Rama and Sita. The saffron background and blue highlights award a kind of brightness to the painting. The human faces are heavy and disproportionately larger as compared to the bodies. Rama, Sita and their attendant are much larger than the others and placed centrally in the compositionto give them prominence. Rama and Sita are circling the fire as part of Hindu marriage rites, as are his four brothers with their brides.[12] The female forms are comparatively tall and wear high cholis like seen in the Basholi school. The composition is square and contains multilevel architectural structures, which is also a characteristic of the Basholi school, taking inspiration from the paintings of the Chaurapanchasika style.

Plate 3: The Marriage Ceremony of Rama and Sita, A folio from the Shangri Ramayana Mandi style, Pahari, Paper, 22.4 x 32.2 cm Acc. No. 62.2436. http://www.nationalmuseumindia.gov.in/pdfs/Ramayan-in-Indian-Miniatures.pdf

The next two paintings from Bilaspur demonstrate the use of nature and its elements thus are examples of a more naturalistic style.The first of these (Plate 4: http://www.francescagalloway.com/usr/documents/exhibitions/list_of_works_url/27/seitz-online.pdf) is a depiction of Rama and Lakshamana, resting on the Rishyamukha mountain and contemplating entering Kishkindha. This relatively less talked about fragment of the story took place after Sita’s disappearance. Rama and Lakshmana came to know from Jatayu that Ravana had kidnapped Sita and proceeded towards Lanka. They encountered a rakshasha[13] named Kabandha, whom they killed. As it so happened the rakshasa was in fact a gandharva,[14]cursed into his present form by Indra. Upon his redemption, he expressed his gratitude by advising Rama to seek Sugriva’s (the exiled vanara king of Kishkindha) assistance to fighting Ravana.[15]

Following his advice Rama and Lakshmana proceeded towards the Kishkindha forest. When they reached its boundaries, and found the Rishyamukha mountain, they decided to rest for the night. The painting illustrates this scene. It is here that Rama and Lakshmana encountered Sugriva, along with his minister Jambavata and associate Hanuman. Sugriva was in a position similar to Rama as not only his kingdom, but also his wife had been usurped by his brother Vali. They helped Sugriva kill Vali and regain his kingdom and wife, thus forming an alliance with the vanaras, who in turn fought on their side against Ravana’s considerable army.[16]

Rama and Lakshmana are shown seated on a green hill representative of the Rishyamukha mountain. The fire burning in front of them and the starry sky with the crescent moon demonstrate that it is night time. The painting is divided vertically into three sections. The hill constitutes the middle section depicting the higher ground. It has four formalised trees of different shapes and forms and is devoid of any other form of vegetation. The section to the side of the hill has been left dark and blank with the exception of one large tree to the left, to once again represent night time. They are carrying bows and arrows as well as swords and are depicted wearing jewelry. Rama is seated on a deerskin while Lakshmana sits on the bare ground. Despite the frugal details, the painting brings out the elements of nature and wilderness effectively.

The second of the Bilaspur style paintings (Plate 5: http://www.nationalmuseumindia.gov.in/pdfs/Ramayan-in-Indian-Miniatures.pdf) depicts Sita in the Ashoka Vatika under Ravana’s captivity, being visited by Hanuman who as per the story had reduced his form to that of an insect in order to avoid being spotted by the rakshasas guarding Sita. He gave Rama’s ring to Sita as proof that he was not one of Ravana’s emissaries trying to trick her and informed her that her husband was on his way to rescue her. This is one of the favourite episodes to be retold and re-enacted from the Ramayana as it symbolises a highly emotional and dramatic moment for Sita. For her this moment is proof of her resolute belief in Rama and his will to rescue her and the first ray of hope that her ordeal is about to be over.

Plate 5: Hanuman in Dwarfed form Appears before Sita in the Ashoka Vatika. Bilaspur style, Pahari, circa 1770, Paper, 30.5 x 40.5 cm Acc. No. 61.1478. http://www.nationalmuseumindia.gov.in/pdfs/Ramayan-in-Indian-Miniatures.pdf

The composition of the painting is interesting because it incorporates both architectural features and natural elements in it and embodies elements that are discernably reminiscent of the Kangra style of painting. The multistoried architectural features to the left point out the influence of the Mughal court and continue the Basholi idiom as do the schematic trees towards the right. The right side of the painting representing exterior space is delineated in the form of a lush green mound. Sita, wearing an orange saree is seated under a rather large tree, on a bed of leaves listening to Hanuman talk. Three rakshasis with demonic faces and grotesque forms are shown sleeping obliviously in front of her. Sita’s porcelain complexion, the comparatively sophisticated colours used in the painting and the silvery gray colour of the water in the foreground are some of the features seen in the Kangra idiom. Once again the elements of nature have been epitomised successfully.

The next painting from Chamba depicts Rama going into battle with his vast army (Plate 6). The scene is set against the backdrop of greenery and hills which have been reduced in scale so as not to overshadow the size and might of the army. Rama rides a large elephant that has been prepared for battle with full armour. He is accompanied by Lakshmana who sits behind him, waving a flywhisk and Hanuman who is controlling the elephant. They are all dressed in full battle armour. Rama holds a bow and his crescent tipped arrow in his hands.

The army consists of foot soldiers, horsemen, charioteers and elephant riders. It spreads across the plane of the composition and gives the impression of an imposing force. The soldiers are shown holding spears and flags;the sense of alertness and forward movement is brought out by the postures of the soldiers and the lifted hooves of the horses. At first glance it appears to be a battle scene from the medieval period as the artist has taken inspiration from his contemporary times when illustrating the scene.

Plate 6: Rama going into battle seated atop an elephant and accompanied by Lakshmana and Hanuman. Chamba style, Pahari, eighteenth century,

Gauche painting on paper. Source: http://www.rarebooksocietyofindia.org/postDetail.php?id=196174216674_10151486053806675

The paintings of Guler were in the beginning similar to those from Basholi, being stimulated by the local paintings traditions. Guler was eventually politically merged with Kangra, and gradually the stark backgrounds began to be filled with landscapes inspired by the topography of the hills.[17]The following painting from the late eighteenth century is an excellent example of the latter phase of Guler. It illustrates a battle between Rama and a rakshasa (Plate 7: http://education.asianart.org/explore-resources/background-information/hindu-stories-ramayana-southeast-asia). The scene is set within a hilly terrain made up of peaks and valleys. Ravana’s golden palace is depicted in the background towards the far right. A demonic figure, blue in colour, is shown riding out of the palace on a chariot after taking Ravana’s blessings. The same demon is represented several times in the painting moving forward through the valley and hills. At first he wreaks havoc upon the vanara army while still on his chariot in the middle of the painting. In the foreground, he viciously attacks Rama, who responds gracefully, shooting at the demon with his bow and crescent tipped arrow. The demon is represented twice in the foreground, to highlight the force of his attack. He is an important figure from Ravana’s army (possibly his son Meghanada or his brother Kumbhakarna) whose exact identity cannot be determined through the painting.

Lakshmana stays dutifully behind Rama and looks on, while the vanaras scurry about throughout the composition using branches, rocks and whatever means they can get to respond to the enemy. The intensity of action has been highlighted by the animated forms and diagonal movements in the composition, which also adds depth to the painting. The colours used are sophisticated; various shades of green have been used to differentiate between lower ground and upper ground as well as to highlight the ridges on cliffs. The ground has been further shaded with a pale pink at key points. The branches of the trees are naturalistic and the intrinsic nature of the humans, the vanaras and the rakshashas has been efficiently brought out.

The paintings of Kangra created under the patronage of Sansar Chand (1775 - 1823 CE), have been celebrated for several reasons. They are known for their embodiment of feminine beauty, the realistic representation of nature and their use of landscape to support the mood of the painting. The women of Kangra have porcelain complexions, and a unique combination of innocence and wisdom. Nature is depicted in a realistic yet stylised manner reflecting a fine balance. Blossoming sprays indicate love in union while barren branches echo the desolation of separated lovers. The beauty of the hills is beautifully captured using perspective and atmospheric layering.

The next two paintings featured in this article are from Kangra. The first of the two is a representation of Maricha trying to dissuade Ravana from kidnapping Sita (See banner image). As per the narrative, when Ravana decided to kidnap Sita, he left his golden city Lanka, which was situated in the middle of the ocean, crossed a sea full of fantastic creatures in his gem-studded chariot. He found the demon Maricha, who had the power to change his form at will,[18] practicing asceticism in the forest and asked him for his assistance. Maricha was terrified by Ravana’s intention and tried unsuccessfully to dissuade him. When he failed, he transformed himself into a golden deer in order to tempt Sita who was possessed with the idea of owning the deer’s beautiful golden skin the minute she laid eyes on it. She persuaded Rama to hunt the deer. Thus, Maricha succeeded in luring Rama into the forest and cleared the path for Ravana to kidnap Sita. In the process he lost his own life.[19]

A large portion of the composition is filled with a swirling ocean in silvery shimmering colours. Represented in a manner quite similar to depictions of rivers in Kangra paintings, it appears to flow out from behind a hillock and has a jagged bank lined with mossy grass. It is however, filled with fantastical creatures, staying true to the narrative while highlighting the wild and distant nature of Maricha’s retreat. The silhouette of Ravana’s golden city is seen towards the far right of the composition.

Ravana and Maricha are shown twice, first towards the middle of the painting where Maricha raises his arms in alarm over Ravana’s plan. The second time he and Ravana are shown riding away on a chariot towards the far left of the painting. They are surrounded by hills and greenery that is topographically similar to that of the hill regions. Ravana is depicted with ten heads and twenty arms. He holds various weapons in each of his arms and wears a pyazi pink jama, commonly worn by Rajput men in the medieval period. Maricha is represented red in colour, portly in form with a demonic face, bird-like feet with talons and horns on his head.

The Kangra workshop had reached its pinnacle by the late eighteenth century, both in terms of creative as well as technical excellence. This composition is an example of the confidence and brilliance of the Kangra artists in conveying the story using sophisticated colours, finely delineated forms and surety of line. A unique feature of the Kangra style is the manner in which they depicted the lush foliage and vibrating natural beauty of the hills. Even though this particular incident is from an ancient epic and believed to have taken place in a land far off, the artist could not stop himself from bringing in the typical idiom of Kangra into the painting.

The last painting to be discussed represents Rama, Sita and Rama’s followers beginning their return to Ayodhya in the flying chariot Pushpaka Viman (Plate 9: http://www.francescagalloway.com/usr/documents/exhibitions/list_of_works_url/27/seitz-online.pdf). The chariot is depicted as a resplendent and grand, golden vehicle. Rama and Sita are seated on an elevated section in the middle of the chariot. There is a pyramid-shaped open superstructure above them supported by four golden poles. Four more poles containing saffron banners are positioned on each corner. Lakshmana, Hanuman, the monkeys and Jambavat are seated at a lower level along with some musicians. Vibhishana[20] and the rakshasas stand outside the chariot to bid farewell to the victorious group. Vibhishana showers them with gold coins as a mark of respect and some rakshasas are shown bending down to pick up the golden coins while others carry trays laden with coins that are yet to be showered.

This scene is also set within the backdrop of greenery and hills like the previous one. The ground is a soft mossy green, interspersed with gentle hillocks and dark green trees. The facial formula of representation developed by Kangra artists included large lotus bud shaped eyes, sharp features, serene expressions and a calm demeanor. This can be seen in all the human protagonists namely Rama, Sita, Lakshmana and the musicians. The vanaras are shown uncharacteristically composed and ordered when seated in the Pushpak Viman. Some of the rakshasas assisting Vibhishana have an air of composure while others gleefully scramble to collect the fallen coins. The overall effect of the painting is one of tranquility, highlighting the end of a violent phase and heralding a period of peace. The painting uses a lot of gold creating a sense of opulence, celebrating Rama’s period of exile and his return to Ayodhya as a hero, victor and king.

The Ramayana achieved the status of a religious text inspiring spirituality very early on because of its all-encompassing nature. It is a collection of many stories woven into one large epic that provides a guideline for the right code of conduct. Its stories evoke a wide range of emotions that support creative expression and hold the imagination of the audience, allowing them to form a deep connection. Rama acquired a divine character in Indian culture and began to be worshipped as a god, believed to be an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. The Pahari paintings contain illustrations based on Ramayana stories well known in popular culture, as well as lesser known accounts. Thus, we see that the Pahari miniature artists took the Ramayana and the mythical figure of Rama and adapted its presentation to suit their own style of illustration while remaining true to the original story. There were multiple dynamics at play in the representation of the imagery, owing to the various Pahari schools. Each of them contributed to the evolution of Pahari miniatures by incorporating indigenous and external influences while adapting the paintings to suit the unique form of expression of each of the sub-regions.

Notes

[1] William Dalrymple, ‘The Beautiful, Magical World of Rajput Art’, 2016. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/2016/11/24/the-beautiful-magical-world-of-rajput-art/ (accessed 8/10/17)

[2] Krishna Chaitanya, ‘Pahari centres’. in Arts of India: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Music, Dance and Handicraft (Abhinav Publications, 1987), 61.

[3] Chakravarthi Raghavan and Surinder M. Bhardwaj, ‘Himachal Pradesh’, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/place/Himachal-Pradesh

[4] Chaitanya, Pahari Centres Arts of India: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Music, Dance and Handicraft, 61.

[5] Raghavan and Bhardwaj, ‘Himachal Pradesh’

[6] Chaitanya, ‘Pahari centres’. Arts of India: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Music, Dance and Handicraft, 61.

[7] Ramayana – literally means Rama’s journey

[8] Encyclopaedia Britannica, ‘Ramayana – Indian Epic’, 2017, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ramyana-Indian-epic

[9] Vanaras – (van+nar) literally translates to forest people. They were inhabitants of the Kishkindha forest, possibly jungle dwellers who had totemic beliefs associated with monkeys.

[10] A destructive weapon, mentioned often in Hindu mythology. It was believed to be obtained by offering penance to Lord Brahma, or from a Guru who knew its invocations. It was meant to annihilate the enemy, so was only used as a last resort to avoid collateral damage.

[11] Janaka – Sita’s adoptive father.

[12] Rama’s three brothers married Janaka’s three daughters at a joint marriage ceremony at the same time as Rama and Sita.

[13] In Hindu mythology rakshasas are believed to be cannibalistic beings, also called Nri-chakshas/Kravyads (maneaters).

[14] Gandharvas are distinct heavenly beings in Hinduism and Buddhism; it is also a term for skilled singers in Indian classical music.

[15] Vettam, Mani, Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass1975), 361–2. ISBN 0-8426-0822-2.

[16] Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and Margaret E. Noble,Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists (NYC: Dover Publications 1967, 61) https://archive.org/stream/cu31924023005162/cu31924023005162_djvu.txt

[17] Chaitanya, ‘Pahari centres’. Arts of India: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Music, Dance and Handicraft, 62.

[18] Coomaraswamy and Noble, Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists, 19.

[19] Coomaraswamy and Noble, Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists, 55-57,

[20] Vibhishana – Ravana’s younger brother, who informed Rama of Ravana’s weakness thus helping to slay him. He was crowned the king of Lanka after by Rama after Ravana’s death.

Bibliography

Archer, W.G. Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills, Vol. I & II. London: Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications Limited, 1973

Chaitanya, Krishna. ‘Pahari centres’. In Arts of India: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Music, Dance and Handicraft. Abhinav Publications, 1987, 62.

Chaitanya, Krishna. A History of Indian Painting: Pahari Traditions. Abhinav Publications, 1984

Chakraverty, Anjan. Indian Miniature Painting. Lustre Press, 1996. 75, 86.

Coomaraswamy, Ananda K., and Margaret E. Noble. Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists. NYC: Dover Publications, 1967.

Daljeet, & V.K. Mathur. Fragrance in Colour. National Museum, 2003. 10, 12, 21 and 22

Devadhar, C.R. Raghuvamśa of Kālidāsa. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1997. 229.

Goldman, Robert P. ‘The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India: Balakanda.’ Princeton University Press: 1990. 34–37, 124.

Goswami, B.N. Nainsukh of Guler: A Great Indian Painter from a Small Hill-state. Niyogi Books, 2011.

Goswami, B.N., and Eberhard, Fischer. ‘Pahari Masters: Court Painters of Northern India’. In ArtibusAsiae Supplementum, Vol. 38, 1992. 3–391.

Khandalavala, Karl. ‘Portfolio - The Bhagavata Paintings from Mankot’. Lalit Kala Akademi, 1981.

Lal, Mukandi. Garhwal Paintings (Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Government of India, 1968), 1982.

Ohri, Vishwa Chander, and Joseph, Jacobs. ‘On the origins of Pahari Painting’. Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1991

Pal, P. ‘Ramayana Pictures from the Hills in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’. In Ramayana Pahari Paintings, edited by R.C. Craven, Jr. Bombay: Marg Publications, 1990. 87–106

Randhawa, S. and J.K. Galbraith. Indian Painting: The Scene, Themes and Legends. Boston (Houghton Mifflin Company), 1968.

Seth, Mira. Wall Paintings of the Western Himalayas (Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, 1976.

Ramcharitamanasa, https://www.ramcharitmanas.iitk.ac.in/

Singh, Chandramani. Centres of Pahari Painting. Abhinav Publications, 1982.

Srivastava, R.P. Punjab Painting - Study in Art and Culture. Abhinav Publications 1983).

The Ramayana of Valmiki. Translated by Hari Prasad Shastri. London: Shanti Sadan.

Williams, George Mason. Handbook of Hindu Mythology. ABC-CLIO, 2003. 166–7.