Ravana overpowers Jatayu. Image credit: Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections.

The location of origin for the group of miniature paintings which art historians identify by the name ‘Malwa’ remains contested; Narsyang Śahar (mentioned in the colophon of the 1680 AD Madhodasa Ragamala) and Nusratgarh (1652 AD Amaru Śataka manuscript) continues to defy identification beyond debate. However, based on dated manuscripts such as the ones just mentioned, and others including the 1634 AD Rasikapriyā (National Museum, New Delhi) and the 1686/88 AD Bhāgavata Purāna (Poddar collection, Kolkata & Kanoria collection, Patna), scholars are of unanimous opinion that the paintings belong to the seventeenth century.

Stylistically, ‘Malwa’ miniatures have been classified into two broad tendencies: Dr Anand Krishna has named them sub-schools ‘A’ and ‘B’ respectively, where the first is characterised by an earthy vivacious character, while the second is relatively refined and sophisticated in its pictorial diction, somewhat restrained in comparison. Of the Rāmāyaņa manuscripts within the ‘Malwa’ school, the folios in the Bharat Kala Bhavan and the Kanoria collection belong to the livelier sub-school ‘A’, which is the focus of this brief essay. Stylistically close to the 1634 AD Rasikapriyā, the set has been ascribed a date of c. 1640 AD. While there is nothing written on the painted surface, the reverse of each folio has a short one or two-line statement in Bundelkhandi dialect stating the theme of that folio. These brief ‘texts’ are distinct from the elaborate passages of poetry in the Rasikapriyā or Amaru Śataka manuscripts. And yet, since the Rāmāyaņa is essentially a narrative, it should be pertinent to investigate a ‘text-image relationship’ between the written word and the painted image on the folios of the manuscript. If the short passages seem too cryptic for the analysis of such an interrelationship between the written and the painted, one could consider a counterpoint argument, such as that of Grace Morley who opined that these ‘manuscripts constituted of albums, the story told in pictures, to be leafed through and enjoyed’[1].

The issue of text-image relationship becomes even more pertinent if one were to ask whether the Vālmiki Rāmāyaņa could have possibly been the source of inspiration for the painted narration in this manuscript, or whether one must look towards other sources as reference—a query that becomes valid if one ‘reads’ the tenor of the images to be entirely distinct from the essentially ‘classical’. Dr Anand Krishna, made a significant observation, that the painter(s) of the c. 1640 AD Rāmāyaņa must have been influenced by the spirit of popular Rāmāyaņa performances like the Rāmalīla[2]. True to his inference, throughout the paintings in this manuscript, the performative emerges as a dominant mode, more so in the scenes of combat, where confrontation invariably seems to have been transmuted into syncopated war-dance rhythms. Gestures are harmoniously coordinated, and softly glide from one into the other, as if in sequence, while the heightened expressions in the faces amplify the feeling of enactment.

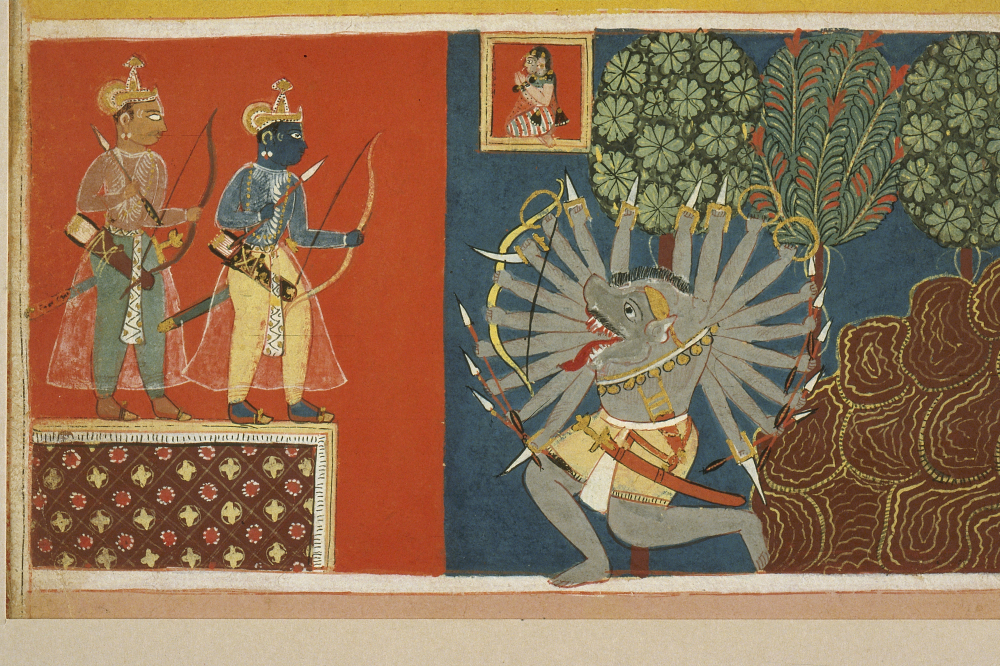

Nowhere is performance more apparent than in the depiction of the demons—the ‘grotesques’ of the narrative. Portrayed with tongues lolling out of huge open mouths set in weird facial features, the sheer absurdity of their forms spell them out more as characters being ridiculed rather than the awe-inspiring and fearsome which they are expected to be. Reducing them to absurdities, then, the painter joins in the mirth and laughter that his demons provoke in the prospective viewer. Comical instead of diabolic, they are predestined to engage in a losing game, where humorous delight is generated at the cost of their plight.

Consider, for instance, the folio depicting the Hanumān-Jambumāli battle (Bharat Kala Bhavan collection). Keeping a single tree strategically in the centre of the compositional space, the warring opponents face each other on either side of this axis, their arms almost mirrored in position, emphasising symmetry; rather than a real battle of forces, the sum total of their posture and gestures seem to take them eternally round and round the central upright. Even if one found a very distant strain of war in their actions, the smaller monkeys disperse the possibility through their impish actions—the one on the right of the tree turns around, teasingly sticking out its tongue in provocation, as if it were more play than battle. With ferocity thus nullified and neutralised, one can only gleefully delight in the expression of Jambumāli’s companion, whose disproportionately enormous head and gaping mouth becomes a yawn rather than a roar. A closer look reveals that barring their faces, the two combatants have more in common than difference—similar physique and dress turn actual battle into masked play; if hypothetically there could have been an interchange of masks, would that serve to reverse roles? The dividing line between the grotesque and the non-grotesque becomes curiously hair-thin.

The distinctiveness of the ‘Malwa’ Rāmāyana paintings must be comprehended as much in their thematic focus as the linguistic rationale of pictorial expression. Space is not an illusory component in the two-dimensional world of the ‘Malwa’ miniatures. Space is rather a charged ambience, usually saturated with hues of red or yellow, sometimes blue, which turns it into an expansive domain—the ‘field’ as it were—a necessary receptacle for the forms it holds within. ‘Two-dimensional’ is a somewhat elusive term to employ, because it must not necessarily imply a ‘flattening’ that eschews dimension, even depth; nevertheless that sense of dimension is certainly not one of infinite recession, perpendicular to the plane of the painting. Rather than being a privileged mode of articulation, illusionistic naturalism is but one of the many options within pictorial exercise, a ‘code’, which like all other codes succeeds or fails depending upon the extent to which its rationale is a shared experience and understanding within a viewing community.

In that ‘two-dimensional’ language of colour characterising the ‘Malwa’ miniatures, a predominantly prominent hue is red. To take an obvious instance, the necessity of situating the figure of Rāma against the brilliance of red spaces was to opt for a colour of such intensity that would effectively contrast with the dark blue of his complexion, such that through this contrast, he may incontrovertibly be projected as the character of central significance.

Fig. 1: ‘Rama attacks the demon Kabandha’, Malwa, ca 1640 CE. Courtesy - Accession number: ACSAA_4236. (Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections.)

This visual strength of vermillion passages against the more somber blues, greens, browns and yellows, is evident in almost each folio. Through our habitual association, wherever red envelops the protagonists, it tends to assume an implied symbolism: for instance, when it envelops Rāma, red becomes synonymous with the positive and the righteous. In the painting depicting Rāma confronting the multi-armed demon Kabandha, the warm brilliance of red saturates the space, which the former inhabits. In the same picture, another small unit holding Sītā is also painted red. While at a formal level, it certainly serves to distinguish the space occupied by Sītā from the blue-grey of the demon, there is also an associative notional continuity from the space that holds Rāma; by extension the brilliance of red around Sītā resonates similarly with virtues Sītā is supposed to represent.

To reiterate our previous contention, the performative is a strong force in this painting, and the radial display of arms by Kabandha is more an attempt towards spectacle rather than actual combat. A common philosophic dimension in the epics, where a demon is killed in battle, is to translate the incident as an emancipation of a trapped soul. The Kabandha episode is no exception, where after his liberation he helps to further the narrative, like an useful link in the chain of events, by informing Rāma about Sugrīva, and suggesting that a friendship with the monkey-hero would be helpful in tracing the abducted Sītā.

Considering that to be the extended storyline of the episode, if we turn to the yellow bordered red square space that holds Sītā in this painting we might progress a shade closer to our comprehension of the mode of narration in ‘Malwa’ miniatures. This enclosed space, distinguished from the rest of the picture, is indeed ‘separate’, as Sītā sits ‘within’ it, hands folded together praying for her release. This visual snippet is a portion of Lankā, a reminder of the fact that she has been abducted by Rāvaņa and patiently awaits her release. More importantly, this small ‘inset’ space is a reaffirmation that the present event will eventually lead on to it. In effect, then, not everything visible within the outer limits of a particular painting need necessarily be of the same location, as an optically singular experience, but may be temporally linked across distances, sometimes even through recollection and remembrance.

The abduction of Sītā (from the Araņya kānda, the third chapter in the epic) is spread over multiple paintings. Having failed to entice Sītā with his eulogy of her beauty, or to frighten her by his ferocious appearance and boasting of his strength, Rāvaņa forcibly carried her away to Lankā, while Rāma (and Lakşmaņa) remains distracted by Mārica disguised as a golden deer. On his flight, Rāvaņa had to confront the opposition of the bird Jatāyu who had sworn loyalty to Rāma and promised to protect Sītā. The Rāmāyaņa narrates how despite his advanced age Jatāyu offered sufficient resistance: he broke Rāvaņa’s bow, tore off his armour, killed the mules of this chariot and the charioteer, and finally attacked Rāvaņa himself, before he was mortally wounded when Rāvaņa dealt a lethal blow to his wings and perhaps also his legs.

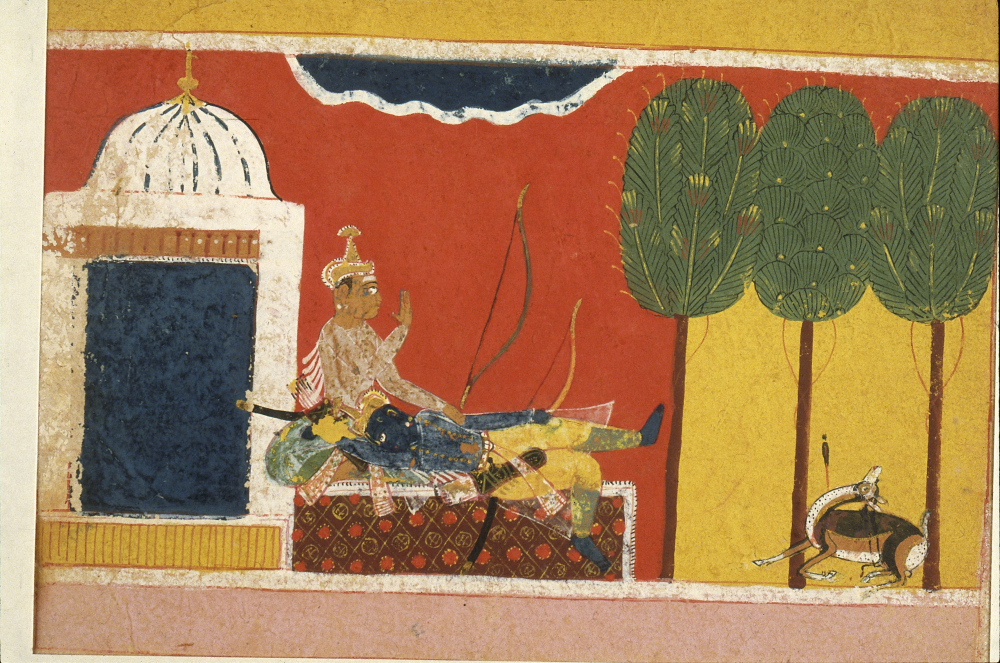

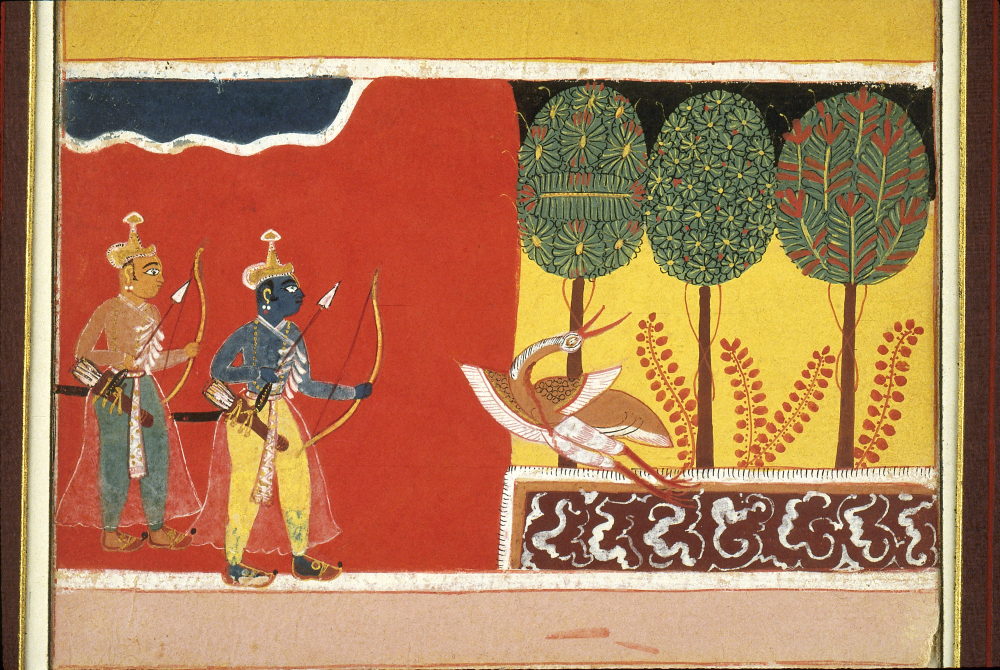

Among the folios from the c. 1640 ‘Malwa’ Rāmāyaņa dealing with the abduction of Sītā are two paintings, one showing the killing of Mārica, and the other depicting Rāma meeting the wounded Jatayu; both images utilise a common compositional schema for different purposes.

Fig. 2. Rama pursues the golden deer and returns to find that Sita has been abducted by Ravana [Lakshmana consoles Rama after the loss of Sita], Malwa, ca 1640 CE. (By the permission of UM History of Art Visual Resources Collections History of Art, University of Michigan, Accession number: ACSAA_4440.)

Fig. 3: Rama and Lakshmana find the dying Jatayu, Malwa, ca 1640 CE. Courtesy - Accession number: ACSAA_4441. (Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections.)

In the first painting, Mārica disguised in the form of the golden deer lies dead pierced by Rāma’s arrow, while Lakşmaņa consoles his brother outside their forest dwelling—obviously after realising that this ploy of distraction has enabled the abduction. In the second, the same basic setting of three trees (evidently standing in for the forest) now depicts the death of Jatāyu after he conveys the news of the abduction to Rāma. Blood flows from his wounded neck, while creepers growing sinuously upwards from the ground echo the anguished bend of the dying bird’s neck. The ‘Malwa’ painter places the dying Jatāyu strategically on the carpet-like pattern of brown and white, which in the previous folio was the ‘ground’ on which Rāma and Lakşmaņa were seated; the significance of Jatāyu—in contrast to the bare ground for dying Mārica—is visually underscored.

The battle between Jatāyu and Rāvaņa (Kanoria collection) shows the bird-hero twice; once in the act of fighting, and then fallen on the ground (See: banner image). Surprisingly, both the images of Jatāyu are actually the same form, only the orientation has shifted.

And this small change of orientation makes all the difference in expression between an erect and strong bird and a mortally wounded one. The same features—open beak, red tongue, wide spread-out wings and a raised right-leg—expressed defiant valiance and challenge in the first instance, and with equal sympathy now conveys anguish and pain when he lies wounded. Evidently, the painter was not only aware of his ‘limited’ repertoire but knew even better, how to harness them for optimal expressive purpose.

His chariot destroyed, Rāvaņa had to fly to Lankā with Sītā. Leaving the wounded Jatāyu, he came and ‘seised Sītā by the hair. The whole world seemed to have been shocked by Rāvaņa’s atrocities. The wind stopped blowing and the sun became pale at the sight of Sītā’s plight . . . Sītā was weeping bitterly when Rāvaņa carried her through the sky. Her jeweled anklets and necklaces slipped down on the earth . . . She tied in her silken scarf all her ornaments and threw them down with the hope that they (the monkeys) would collect them and convey her abduction to Rāma (P. Banerjee[3]).’

It is worth pausing in detail over the following painting from the ‘Malwa’ manuscript (Bharat Kala Bhavana collection) which shows Rāvaņa still wearing the garb of a mendicant as he carries Sītā to Lankā. However, this disguise is far from the saffron robe of Vālmikī’s description. Bhanu Agarwal points out the dress to be related to the Kānphaţa sect of medieval India, popular especially in Rajasthan[4]. While the stick in his hand is not the one mentioned by Vālmikī (from which he is supposed to have hung the water-pot), the cap on his head is another peculiar feature. Bhanu Agarwal links it with Sir Thomas Roe, who is supposed to have worn such a cap when he met Jahangir. If that be true, then we are perhaps observing an interesting sociological comment by the artist; that, like the foreigner, Rāvaņa came from ‘across the ocean’. The Rāvaņas in the two consecutive folios of this episode are so different in physiognomy, colour of the body, and the shape and colour of the cap on their head, that one is tempted to ask if they were done by two different artists working on the same manuscript.

P. Banerjee quotes Vālmikī’s description of Rāvaņa’s recklessness while abducting Sītā, thus: ‘Blind with lust and passion, he lifted Sītā catching hold of her lovely tresses with the left hand and clasping her thighs with the right. The presiding deities of the forest fled in terror at the sight of Rāvaņa.’ Contrary to any such brutality the Rāvaņa of the Bharat Kala Bhavan folio holds aloft his tiny captive with much loving care on his outstretched palm; as if she were a treasured gem. To the Malwa painter of this folio, the rakşasa was a soul hopelessly entangled in his love of beauty, an image of tender infatuation, strongly coveting the object of his desire. Not until we reach the monarch inside his golden city, besieged by the army of men and monkeys, do we come across the ten-headed twenty-armed menacing form of the demon-king.

The most fascinating use of a brilliant length of red is to be found in this folio; while it serves to compositionally elucidate the theme of the episode, it also stands apart from any symbolic association with piety or righteousness that the colour may have acquired elsewhere. Partly within the end of this red stretch of colour and already crossing into the brown of the hills, the figure of Rāvaņa with his extended arm and leg, has a strong sense of movement. And due to this quality of movement and his position at the end of this strip of colour, the red takes on the feeling of traversed space which the demon has just covered. On the other hand, that same red sheet of colour is punctuated by the curves of the ornaments and the garland thrown down by Sītā, where repeated arcs give them the necessary directional sensation of falling ‘down’, towards the trees below. If we can agree that the elements of this painting do give us even a fraction of these sensations, then even within the planar treatment of colour and the two-dimensionality of the language, somewhere the threshold has been crossed; such that we have no difficulty to see how, Rāvaņa has crossed ‘over’ the tree-tops, ‘above’ the rocky terrain infested with grimacing demonic creatures, and is now poised to leap ‘across’ the waters in a single stride.

The ‘Malwa’ Rāmāyaņa is an excellent example to comprehend the functioning of pictorial language outside the domains of illusory naturalism. The efficacy of the so-called ‘two-dimensional’ mode of articulation and the possibility of the interpretative width of such a pictorial language offers a classic opportunity in ‘reading’ a picture. To sum up, we can once again cite a painting depicting a moment prior to the battle, where Rāma waits for Hanuman to fly across the ocean and bring back news from Lankā.

Fig. 4: Hanuman returns to Rama from Lanka, Malwa, ca 1640 CE. Courtesy - Accession number: ACSAA_4444: (Regents of the University of Michigan, Department of the History of Art, Visual Resources Collections.)

The yellow bordered blue unit in this painting, containing a demoness keeping guard over Sītā, is certainly not part of the space that is physically continuous from that of Rāma and the monkeys: rather, it is what Hanumān sees in Lankā, and the news he brings back for Rāma. Much like a Rasikapriyā folio depicting Kŗşņa’s elegant appearance being conveyed by the sakhī to Rādhā, the ‘inset’ in the Rāmāyaņa painting corresponds to what Hanumān speaks to his master: it is the concrete (visual) rendering of speech—the verbal concretised into the visual.

In conclusion, it shall prove worthwhile to contemplate a passage from Geeta Kapur[5], where she writes about the traditional Indian concept of space in a painting: ‘Space or Śunya is this ‘felt’ substance, solid and compact’. She observes that the traditional Indian painter knew how ‘to take an expanse of, say, cadmium yellow and make it work as a solid sheet of coloured space, and at the same time as a lucent sky or lighted void where his images are held suspended like pictures in a magic lantern’. It is against that solid colour-space, which is at the same time a lighted void, that the protagonists of the ‘Malwa’ miniatures move about—demons threaten heroes or lovers pine away for each other—all against that glowing, luminescent, sheet of colour.

Notes

[1] Grace Morley, ‘The Rama Epic and Bharat Kala Bhavan’s collection’, in Chhavi-2, Rai Krishna Das Felicitation Volume (Varanasi: Bharat Kala Bhavan, 1981)

[2] Anand Krishna, Malwa Painting (Varanasi: Bharat Kala Bhavan, 1963?)

[3] P. Banerjee, Rama in Indian Literature, Art and Thought (N. Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan, 1986)

[4] Bhanu Agarwal, ‘Literary background of Malwa Ramayana Paintings in Bharat Kala Bhavan’ in JISOA, Volume XII-XIII, (Kolkata: Indian Society of Oriental Art, 1981-83)

[5] Geeta Kapur, Contemporary Indian Artists (New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1978)

Bibliography

Agarwal, Bhanu, ‘Literary background of Malwa Ramayana Paintings in Bharat Kala Bhavan’ in JISOA, Volume XII-XIII, Kolkata: Indian Society of Oriental Art, 1981-83)

Banerjee, P., Rama in Indian Literature, Art and Thought, N. Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan, 1986.

Kapur, Geeta, Contemporary Indian Artists, New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1978.

Krishna, Anand, Malwa Painting, Varanasi: Bharat Kala Bhavan, 1963.

Morley, Grace, ‘The Rama Epic and Bharat Kala Bhavan’s collection’, in Chhavi-2, Rai Krishna Das Felicitation Volume, Varanasi: Bharat Kala Bhavan, 1981.