Case Study of the Anthropology Collection of National Museum, Delhi

The story of Rama or Rama Katha is very popular in its theatrical presentations in various forms of traditional dance-drama based performances in India. This tradition, which developed during the ancient times, became fully manifest during the medieval centuries that is continuing on till today. Marked by the emergence and spread of the Rama cult around 14th century CE, the performance of Ramayaṇa as a theatre spectacle was introduced in different regions of India. The performance-based tradition became assimilated in the folklore and ethnic cultural spheres where it took a unique form, interwoven with indigenous flavours, developing a plurality of local, sub-regional styles.

As the Ramayaṇa recitation gained popularity and became imbibed as an art form into the indigenous oral traditions, a unique form of story and performance manifested through visual forms. These dramatic performances involved tangible and intangible art forms, including oral traditions, folk songs, dances, pantomime and artistic manifestations, which are embedded with symbolic connotations denoting self-experiences, collective memories, life-patterns and religious and ritualistic significance. The Ramayana based performances became recognized as a popular source of entertainment since they were performed during festivities, commemorating a sacred event and also regarded as part of cyclical gatherings.

The traditional style of dramatic performance of Ramayana is commonly known as Ramlila, meaning ‘actions of Rama’, deeply rooted in the primal concept or expression of religious devotionalism to Rama (Ramabhakti). The dramatic performances are presented in a variety of styles and forms, employing varied modes of expressions, displaying an array of cultural and regional distinctions, characterized by their indigenous shades, yet closely following the narrative order prescribed in the textual sources.

The story is presented as a pantomime, comprising of serialized representations of episodes in a specialized staged setting along with processions and tableaux, where special importance is given to the religious rituals and presentation techniques. The performers enact the roles of different characters in the story, very realistically, manifested through their stylized movements, actions, recitations or singing. They are decked in bright, vivid and fascinating costumes, make-up and masks, which characterize identification of their role in the play. Based on oral tradition, the episodes are beautifully sung as part of a bardic cult in a theatrical set up where visual forms are a major form of interpretation.

The continuity of the traditional Ramayana theatre can be determined from the textual sources which elucidate the religious significance of epic-based theatrical performances. The literary tradition played a pivotal role in building the popular theatre tradition of the Rama saga. Shriramacharitmanas of Tulsidas has a unique place in this respect, along with Valmiki Ramayana, Tamil Ramayana by Kamba (12th century CE), Kṛttivasi Ramayana of West Bengal (15th century CE) and in Odiya the Jagamohan Ramayana by Balaram Das (16th century CE).

The earliest mention of the dramatic representation of Ramayana occurs in the Harivamsa which is the Khila Parva of the Mahabharata (4th century CE). The living popular theatre tradition is traceable from the Hanumanataka or the Ramayana Mahanataka, a Sanskrit dramatic composition expounded somewhere between 10th -12th centuries, which provides special importance to music and dance. In the later centuries, the Sanskrit epic has undergone innumerable changes with the compositions rendered by different authors in vernacular languages. Based on these, the religious performances, plays, ballads and festivities are performed representing distinctive regional identities and styles.

In India, some of the popular indigenous theatrical traditions representing the Ramayana are: Yakshagana of Karnataka and Kerala, Chhau mask dance and Jatra tradition of West Bengal and Odisha, Kathakali of Kerala and Dashavatara in Maharashtra. Such kinds of epic-based performances also got adopted in various forms of shadow puppet theatre, such as Tolpava Koothu of Kerala, Tholu Bommalattam of Andhra Pradesh, and Togalu Gombeyatta of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. These art forms showcase a strong current of inter-regional cultural diffusion and the visual metaphors originating from them are created under unique social circumstances, bespeaking plurality of regional expressions and styles.

This article aims to showcase select art objects related to the epic-based theatrical performances, such as Yakshagaṇa costumes of Rama, Sita and Ravaṇa, specimens of shadow puppetry from Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Karnataka and varied types of dance and ritualistic masks from eastern India, depicting different characters from the story. The objects discussed here were a part of a temporary exhibition titled ‘Rama Abhirama: The Beauty of Rama in Indian Art and Tradition’ displayed at the Special Exhibition Hall of National Museum, Delhi from December 19, 2017 to January 31, 2018. In this exhibition, a section was primarily conceptualized to provide a glimpse of the myriad depictions of the Ramayana in folk performances. Apart from this, a wide collection of miniature paintings, pattachitras, stone and wooden sculptures, terracotta, bronze icons and textiles were also displayed classified thematically based on the narrative order of the epic.

These objects serve as a part of the Reserve Collection of the Anthropology department of National Museum, Delhi, India and the writer being an Assistant Curator of the Anthropology Department, National Museum, was involved in the curatorial activities of the section that dealt with the Ramayana in Indian tradition, which was thematically divided into theatrical performances, dance masks and puppetry. From the viewpoint of a museum curator,it is believed that interpretation of performance arts originating from religious wisdom if analysed from an art-historical standpoint, in addition to ethnographic dimension, could unfold both the visual and oral narratives and are essential for museum practices and studies.

An exhibition of liturgical and performance-based objects in a museum setting is a challenging task since visual representation of the vast repository of intangible cultural heritage of a community through tangible means in the form of artefacts requires engaging specialized methods and techniques of display because the ritual part of making an object or oral traditions remain unseen. Each object unfolds a story or narrative, embedded with intrinsic values, and is not treated merely as a prop for display.

In this context, museums play a vital role in preserving such diverse artistic forms, recording for posterity by reasserting their religious meanings and restoring the cultural identity of the community, which is involved in their creation.With an aim to create a better understanding of the interrelationships between tangible and intangible cultural art forms,during the exhibition, different methods for creating public orientation and dissemination of knowledge through varied communication modes, including documentaries/videos, digital documentation, outreach and educational programmes were efficiently used in order to capture the history and rich cultural heritage of Ramayana traditions in India.

Mask Dance

Mask dance is one of the most popular forms of performing arts, deeply grounded in religious and festive spirits of the indigenous people of India. Masks play a dominant role in such dance-based performances, to the extent that the masks and dances are inseparable from each other, since both of them bear unique ritualistic significance. Apart from their religious sphere, both mask and mask dance directly and indirectly cast their influence on social life as well. They are also believed to be embodying the soul and identity of the character played by the performer, depicted by their facial expressions, vivid colours and decorations.

These ceremonial dance forms are performed during specific periods by people of particular communities. Costumes befitting different characters are put on along with the masks in the course of the dance by the performers and the dramatic climax of the stories are expressed through vigorous athletic and acrobatic yet stylized dance movements, showcasing a fusion of martial, tribal and folk elements. These performances mainly revolve around the stories of Hindu epics and ancient mythology, yet are integrally associated with folk beliefs and practices. In the midst of a multidimensional socio-religious milieu, the theme of Ramayana entered into folklore and gained utmost significance among various autochthonous communities who started worshipping Lord Rama as an embodiment of valour, virtue and righteousness.

In eastern India, various types of religious mask dances are performed. Chhau mask dance is one of the most popular forms, celebrating the essence of power, war, victory and joy. This religious mask dance is practiced in the bordering areas of the Western Bengal, Bihar, Odisha and Jharkhand. The main centre in Western Bengal is Purulia. These masks are made up of layers of waste paper and rags, which are pasted and then dried out in the Sun. Following this, painting and embellishments are done on the dried mask and the clay is scraped off. In the exhibition, Chhau masks of Rama, Sita, Lakshmana and Ravana, were placed in a hierarchical order, while appreciating the aesthetical values of the object and following the museum display ethics. Each mask displays a different style and artistic treatment and also workmanship, though they belong to the same Chhau mask dance tradition. However, the iconography of each deity is inspired from the textual sources, identified by their complexion and physiognomic features.

The mask dance tradition in Odisha is however distinct and varied types of masks-based traditions are also followed. The Odia versions of the Ramayanais called as Jagmohana Ramyana or Dandi Ramayana. This text is considered as one of the best and the most popular ones among the other adaptations of the Ramayana, authored by Balarama Das of Puriin around AD 1500. Besides this, there are several other forms of the Ramayana composed by various authors, including the Ramayana of the Sarala Das (BilankaRamayana), Upendra Bhanja (Baidehi-bilasa) and Bishwantha Kuntiya (Bichitra Ramayana).

It has been found that there are more than one hundred Kavyas in Odia on Ramayana apart from it these thereare several plays, short poems and diverse types of semi-dramatic forms such as leelas, yatras, etc., on the Ramayana. Besides these, the story of the Ramayana is also performed by different ethnic groups as part of ritualistic practices. For example- in the Koraput region, theRamayanaisperformed in the form of rites and dances. Wooden masks are created which are quite big and weighty. No dancer uses them while dancing. The mask in the function only stands for the symbolic figure of the character. It is believed that the old wooden masks wield spiritual influences so they are kept inside the temples as sacred objects and after that such masks are never used in performances.

Artistic specimens from this community, showing the mask representations of Hanuman, Jamvant and Parshuram were displayed in this same section of the exhibition on a flat pedestal. These wooden masks follow distinct artistic renditions, though the iconography remains fixed. Each figure bears a Vaishnavite mark on its head, bespeaking the religious inclination as well. In Odisha, the tradition of mask-making is also adopted into handicraft, where special attention is given to the Ramayana theme by the craftsmen. Papier mache masks are quite popular and made by using a mould of clay and newspaper which is painted with bright colours. Such masks of Hanuman were also included as a part of this exhibition to showcase the diversity of artistic traditions.

Yakshagana Tradition

Fig. 1: Display of Yakshagana costumes: Rama (right), Sita (centre) and Ravana (left) (Courtesy: Rama Abhirama: The Beauty of Rama in Indian Art and Tradition’, National Museum)

Yakshagana, a traditional form of dance drama, was developed during fifteenth-sixteenth century CE, forming an important part of the Kannada tradition. This theatre style is mainly found in Karnataka and Kerala. As the name suggests, Yakshagana performance is the song (gaṇa) of the yaksha (nature spirits). In this spectacular dramatic presentation, the Ramayaṇa has found adequate expression. Different life events of Rama from his birth up to his triumphal return from exile and also the devotion and melancholy of Sita’s are magnificently captured, narrated and vividly performed.

This folk-dance drama was traditionally presented by an all-male troupe of trained performers, using highly ornamental language fused with a wide variety of music, melodious songs and sophisticated dance movements befitting each character. It is traditionally presented from dusk to dawn. The protagonists wear make-up, costumes and ornaments made of a light wood or kinnal covered with lac and imitation gold leaf. Headdresses of Yakshagana costumes are of different types and sizes; covered with red and black cloth, ornamented with gold and silver tinsel ribbons, lac and limitation gold leaf decorations, beads, peacock feathers and jewellery.

Yakshagana costumes are made in red, green and yellow and are inspired from the popular temple tradition of southern India. The theatrical masks and jewellery too are symbolic in nature. The viewers of Yakshagana are well-acquainted and familiar with the visual codes and distinctions they imply. In this exhibition, mannequins of Rama, Sita and Ravana were showcased to provide a glimpse of this tradition.

Shadow Puppetry

Fig. 2: Display of Tolpava Koothu puppet of Ravana (on the screen), followed by Gombeyatta puppets of Hanuman and Rama and a Tolpava Koothu puppet of Mandodari (centre). (Courtesy: ‘Rama Abhirama: The Beauty of Rama in Indian Art and Tradition’, National Museum)

Shadow puppetry is one of the ancient forms of folk performances, deeply embedded with ritualistic symbolism. It is performed for the entertainment of large audiences, in which stories and myths related to Hindu divinities are presented as a combination of memorized verses, songs, oral commentaries and visual representations. The Ramalila drama is one of the most popular themes of such plays.

The art of leather shadow puppetry flourished in different parts of India, including Odisha, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and in Kerala, but gained much popularity particularly in the Southern India, possibly originating as early as twelfth century CE based on the Kamba Ramayana. As discussed earlier, in Kerala, the leather puppets are called as Tolpava Koothu, while the counterparts in Andhra Pradesh are the Tholu Bommalattam and Togalu Gombeyatta marionettes belong to Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. Similar kinds of tradition are followed in Odisha, called as the Ravanachhaya, and the Charma Bahuli Naṭya in Maharashtra.

In the Kerala puppet tradition, 160 puppets are used to represent the complete version of the Kamba Ramayana, displaying 71 characters in four main categories (sitting, standing, walking, and fighting) besides puppets to depict nature, battle scenes and ceremonial parades. The shadow puppet theatre is presented once a year during the main temple festival and the performance continues for several nights

Some of the salient features of shadow puppetry are the theatrical play of shadow and light and ventriloquism, where invisible skilled performers are narrating the episodes of the Hindu epics and also manoeuvering the physical movements of the puppets with the help of a bamboo stick or strings. The movements of the puppets are very intricate, with the larger puppets having up to 13 different movable body joints. These marionettes are made up of deer, goat and sheepskin and the hide is cleansed treated and stretched till it becomes more translucent and durable. The figure of each character is drawn in an outline and the shape is cut out of it with movable body parts tied together by a string, and then the puppet is painted in vegetable colours, though now synthetic dyes are also used.

The puppets are flat-cut, lightweight and are decorated with perforations which allow light to filter through the material adding luminosity, also making them perfect for lampshades and screens, enlivening any dull and dark room. To create this theatrical setting, the screen is illuminated by lighted lamps, made out of coconuts cut in half, filled with coconut oil, provided with cotton wicks and placed equidistant from each other on the wooden beam behind the curtain. The white screen is tilted forward so that the puppet looks large and powerful and behind the white screen the musicians perform.

The articulation of these leather puppets varies greatly from one region to another, but a degree of consanguinity can be ascertained with respect to the subjectivity of themes and expressions. In Kerala, the reciters of the stories of Rama and Ravana are the male professional bards and singers called Nair kavis, while the storyteller of the drama in Andhra Pradesh is called as sutradhara. This tradition became immensely popular in the Far East and different parts of Southeast Asia as well, particularly in Thailand, Indonesia, Laos and Cambodia.

During the exhibition, to recreate this dramatic experience of shadow puppetry, a separate section was modelled for showcasing these puppets on a higher platform, displayed in different styles, under controlled projection of light and shadow, leaving an impact on the audience. The audience was enveloped by darkness all around, and the light filtering through the perforation of the puppets added luminosity to space, heightening the theatrical ambience of the display. In the display, in one section a screen was specially formed to create a shadow projection of the Tolpava Koothu puppet of Ravana.

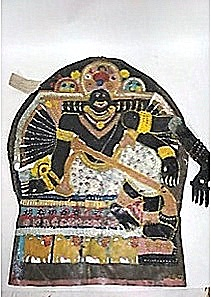

Fig. 3: Tolpava Koothu puppet of Ravana, Kerala, 20th Century, Leather, 75 cm × 61.5cm, Acc No : 79.507(Courtesy: National Museum, Delhi)

This puppet displays the multi-armed and multi-headed demon king as a dark-complexioned figure, playing a veena and seated on a throne. Here, the arms are movable, providing flexibility of movement by strings, while the entire surface is perforated allowing light to filter through the surface. On the other side, selected Tholu Gombeytta puppets of Hanuman and Rama and a Tolpava Koothu puppet of Mandodari were suspended by strings, so as to well-acquaint the viewer with the other types of the shadow puppetry while providing a comparative view of colour renditions, structural formations and also iconographic patterns.

Fig.4: Tholu Gombeytta puppet of Hanuman, Puppet, 20th century, Leather, H. 102cm, Acc No 89.450/40(Courtesy: National Museum, Delhi)

These varied art forms discussed in this paper, display the diverse visual manifestations of the Ramayana in folk traditions thriving indifferent parts of India.They show an amalgamation of classical Hindu iconography and textual prescriptions of the original Sanskrit Valmiki-Ramayana and also folk attributes originating from the local oral traditions. In fact, in course of time, these theatrical based art forms have undergone significant artistic and stylistic changes under the impact of societal and economic development, yet their essence remained intact, glorifying the narrative heroic exploits of Rama, shown restoring the order or law and removing ignorance by his actions though the medium of colours, attributes and stylized forms.

Bibliography

Ashton, Martha Bush., and Bruce Christie. Yaks̨agana, a Dance Drama of India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publishers, 1977.

Banarjee, Asit Kumar.The Ramayana in the Eastern India.Calcutta: Prajana, 1983.

Blackburn, Stuart H. Inside the Drama-house: Rama Stories and Shadow Puppets in South India. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996.

Ranjan Sarkar, Sabita. Mask of West Bengal. Calcutta: Indian Museum, 1990.

Tribhuwan, Robin D., and Laurence Savelli. Tribal Masks and Myths. New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House, 2003.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. Classical Indian Dance in Literature and the Arts. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 2007.

Vēṇu, Ji, and Mulk Raj Anand. Puppetry and Lesser Known Dance Traditions of Kerala. Irinjalakuda: NatanaKairali, 2004.