The radical impulse of documentary practice in India has been deeply informed by its legacy of speaking truth to power. Time and again, the documentary, responding to the changing socio-political climate of the country, has created critical fissures in the dominant discourse of the nation-state. Through engagement with issues of gender, sexuality, class, environment and caste among others, and its solidarity with people’s struggles and social movements, the documentary has continually ruptured public transcripts of state hegemony.

This legacy of activism can be traced back to the 1970s, when the documentary first charted an independent journey of its own, liberating itself from the clutches of bureaucratic regimes. For almost three decades after Independence, the Films Division (FD) was the sole producer and distributor of newsreels and documentary films in India, and was principally preoccupied with the project of national integration. In order to conjure up a unified image of the country, the FD typically commissioned two kinds of films: the first glorified the diversity of India’s cultural heritage, with films based on Indian festivals, historic architecture, cultural traditions and values systems, and the second captured the vision of a newly formed nation and its aspirations for scientific growth, modernization and industrialization.

With the emphasis on creating an image of a ‘traditional yet modern India’, the documentary came to be understood as an informational and educational medium that almost always represented the nation in a favorable light. In an effort to expand outreach, the FD made films available in several languages and made it mandatory to screen them before feature films in commercial cinema halls across the country.

During this period, the FD kept tight control over the content and form of all documentaries in India. It also faced charges of churning out films mechanically and mindlessly (Garga 2007). The strongest critique of these films came from the Chanda Committee Report in 1966, which recommended a complete rethinking of the way in which FD films were being envisioned. It criticized the FD for not developing an engaging cinematic style, for ‘mechanically making them [documentaries] dull and uninteresting’, and for failing to encourage critical thinking in the audiences. It cited examples of an ‘aesthetic lack’, and commented on the absence of 'humour, satire, suspense and drama in documentaries’, features with the potential for deeper impact upon audiences (Roy 2007).

It was from within these strict regimes of creative and financial control that the 1960s saw the first breed of ‘angry’ filmmakers like S. Sukhdev, Pramod Pati, S.N.S. Sastry, K.S. Chari and T.A. Abraham, who were frustrated by the dogmatic atmosphere of the FD. Negotiating with the officialdom of the FD, these filmmakers, through works like And Miles to go…(1965), Face to Face (1967), I am Twenty (1968), Report on Drought (1967) and India ’67 (1967), exposed the inequalities in Indian society and for the first time tried to make an honest statement about the decadent state of the nation.

Out of the group of filmmakers working with the FD at the time, Sukhdev is often considered to be the most radical. Trained under the famous German filmmaker Paul Zils, he was determined to bring together art and activism and made films on various issues such as the railway strike of 1974, the public distribution system, bonded labour and violence. Many believe that had Sukhdev not died prematurely at the age of 46, he would have been perhaps one of the most reputable filmmakers to come out of India.

Despite the impulse of nation-building that drove the FD, the manner in which these filmmakers negotiated their work within a state organization is undoubtedly commendable. This struggle also coincided with a change in leadership that the FD underwent at the time. When the creative freedom of filmmakers was being stifled by the propagandist agendas of the state, the appointment of J.S. Bhownagary proved to be a breath of fresh air. It was under him that for the first time the FD steered in a new direction of critical filmmaking. He encouraged politically critical films and was of the strong opinion that new ideas and approaches had to be found, encouraged, and put to work (Garga 2007). Under his role as chief advisor, he encouraged experiments with the film language, and the development of innovative techniques like the use of found footage, pixilation, and so on was prioritized (Jain 2013).

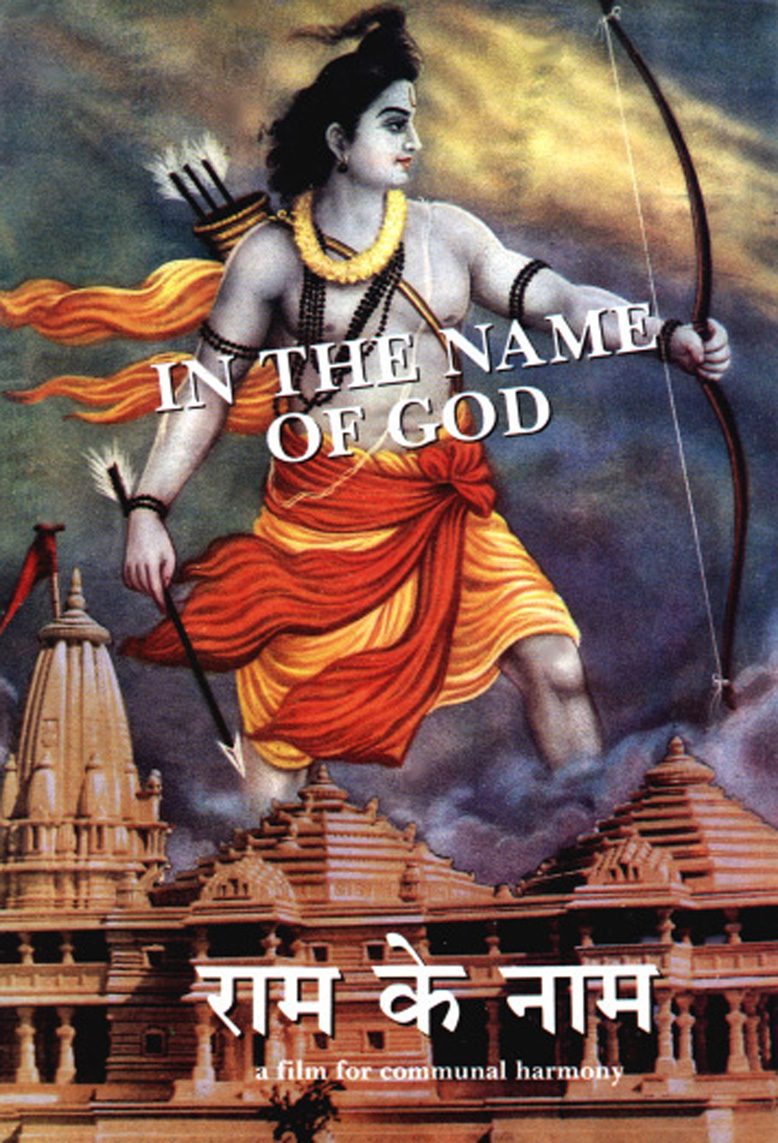

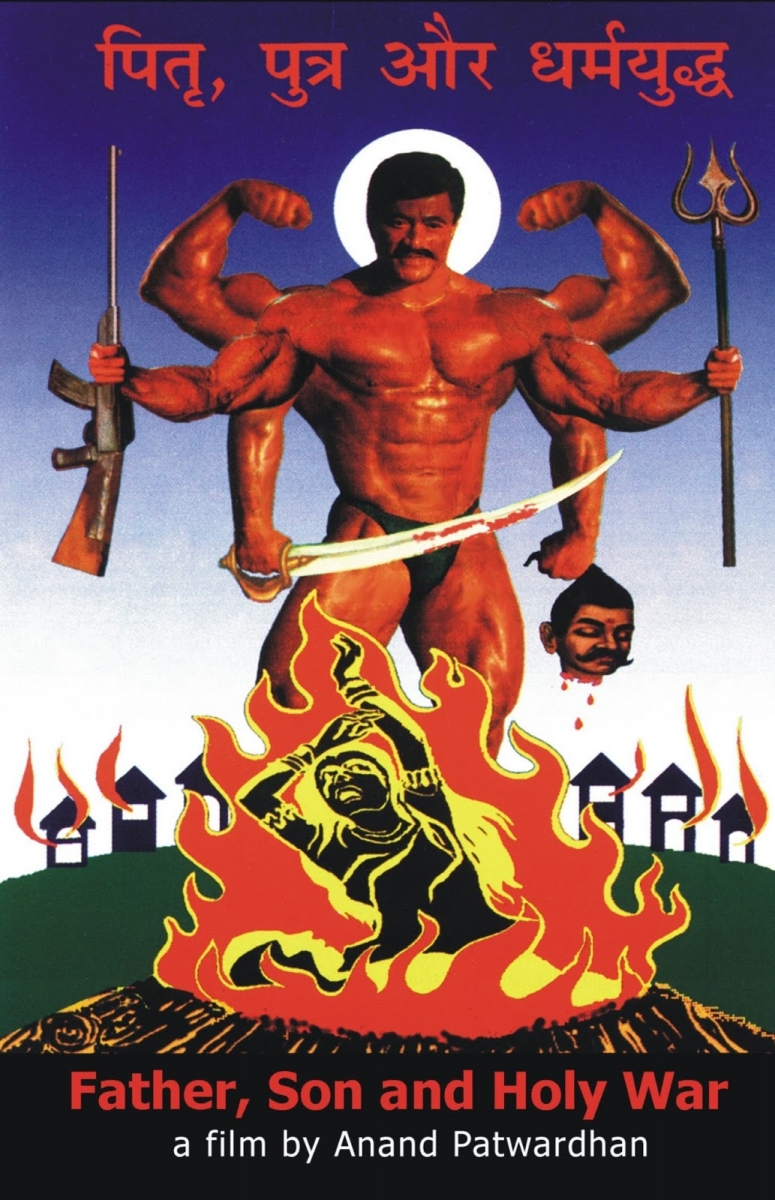

The seeds of dissent planted by the ‘angry’ filmmakers and the support extended by Bhownagary for their growth can be seen as a prelude to what could be called the explosion of radical documentary culture in India. The next decade saw the emergence of a new breed of filmmakers like Anand Patwardhan, Gautam Ghose, Utpalendu Chakrabarty, Tapan Bose, Suhasini Mulay, Deepa Dhanraj and others, who worked completely outside the funding structures of the FD. Through films like Waves of Revolution (1976), Prisoners of Conscience (1978), Hungry Autumn (1974), Mukti Chai (1977), An Indian Story (1981), these filmmakers boldly covered issues of poverty, state-sponsored violence, and even the 1975 National Emergency, posing a sharp critique of the state, this time completely unrestricted by any authoritarian control. They sought sponsorship and outlets from foreign television networks as well as non-theatrical sources within the country (Garga 2007). Thus the idea of India that was being peddled to the citizens for over three decades was challenged by these filmmakers and the growing discontent overlapped with the turbulent political atmosphere generated by the Emergency of 1975–77.

The post-Emergency period is also often marked as the beginning of independent documentary practice in India. Ironically this is also the time when documentaries came under the strict surveillance of the State. Experiences with pre-censorship of films like A Tale of Four Cities (Dir. K.A. Abbas, 1968), An Indian Story (Dir. Tapan Bose, 1981) (a pathbreaking film on peasants jailed by the Bihar State Police), and Beyond Genocide (Dir. Tapan Bose and Suhasini Mulay, 1986) on the Bhopal Gas tragedy, exemplify how the State came down heavily on independent filmmakers who raised political concerns. Some filmmakers also fought court cases to release their films.

This moment of rising film activism further coincided with an important historical moment of the 1980s in terms of a global advancement in the field of technology. The invention of analogue video formats led to the replacement of the old 16mm and 35mm celluloid film, a shift that relieved the new generation of filmmakers from the limitations of importing expensive film stock and taking official permissions, thereby making filmmaking relatively affordable as well as accessible. The arrival of video also triggered new processes of dissemination for documentaries. Freed from the compulsions of the bureaucratic procedures and approvals, filmmakers could now distribute their films independently. The VCR allowed mobility to VHS copies and helped in grassroots-level circulation. VHS copies could be easily distributed through informal and private networks by filmmakers who found no place in state-enabled production support and distribution systems.

This also paved the way for the beginning of independent film festivals—one of the most prominent of which was the Bombay International Film Festival (BIFF), first held in 1990— that provided alternative exhibition opportunities to filmmakers. As opposed to being slotted before commercial films in cinema halls—a practice of the FD, which some would say had an effect opposite to the intended one of creating an appetite for documentaries among Indian audiences—the film festival over the decades has come alive as a space to redefine and re-cultivate a flourishing documentary-viewing culture in India. Today the country boasts hundreds of film festivals and film clubs at regional, national and international levels, committing themselves to designated and specialized themes in areas such as environment, gender, tribal rights and cultural activism.

The 1980s was also an exciting time for documentary practice as it saw the emergence of filmmakers who stood in solidarity with the women’s movement and used documentaries as a tool of expression, activism and advocacy. Directors like Deepa Dhanraj, Meera Dewan, Reena Mohan, Manjira Datta, Madhushree Dutta, Sagari Chhabra and Shabnam Virmani took upon themselves the responsibility of exposing the structural violence inherent in the social, political and economic realities of the country with a focus on the deplorable condition of Indian women. They also brought the idea of women’s identity to the forefront of the nationalist debate. Influenced by the changing political and economic understanding of development globally, filmmakers covered a range of issues concerning government policies, dowry, rape, socialization of women, sexuality, self-image and beauty and so on, while also bringing to the fore many grassroots struggles.

At the same time the filmmakers also grappled with questions around their own subjective positions as filmmakers, which led to the development of a new aesthetics of self-reflexivity—the gaze of the camera turned inwards and the slogan of the women’s movement, ‘the personal is political’, began to get reflected in the medium of the documentary film. Some of the landmark films of this time are Molkarin (1981), Gift of Love (1982), Kya Hua Is Sheher Ko? (1987), Something Like a War (1991), Tu Zinda Hai! (1995), When Women Unite: The Story of an Uprising (1996) and Skin Deep (1998).

Over the years, with the coming of the hand-held home video camera, the idea of ‘political’ has expanded beyond critiquing the government and has changed to looking within one’s self and one’s own household to explore the power politics of the everyday. This kind of personal inquiry has facilitated the making of films on issues such as class divisions, communalism and LGBT struggles in recent years.

The 1980s are also significant to documentary practice as they witnessed the formation of several media collectives and community video initiatives to include larger numbers of participants in the political struggles of the country. Initiatives like Yugantar, Mediastorm (India’s first all-women documentary film collective), CENDIT, Alternative Communication Forum and Drishti Media Collective sprung up in different parts of the country. These platforms also served as stepping-stones for building a strong relationship between activists and the academia, one that continues to support the documentary screening culture in the country till date.

The new potential for documentary films to reclaim their role in the public life of India encouraged filmmakers to seek alternative exhibition strategies, especially through the support of European distribution networks, to counter obstructions in reaching out to audiences and making themselves heard. Within India, until the satellite television boom in India in the early 1990s, state broadcaster Doordarshan's two national terrestrial channels were the only TV networks in India where documentary films could be screened. The launch of Discovery Channel in India in August 1995 and the subsequent entry of National Geographic Channel in 1998 created further avenues for Indian filmmakers, especially for those working on wildlife and environment issues (Lall 2004). Today television channels like NDTV, DD National and Lok Sabha TV have started regularly hosting several independent and commissioned documentaries, although many filmmakers complain that news channels are careful not to include films which are ‘too political’ in nature.

The digital turn in the 21st century had a great impact on the production and distribution mechanisms of the documentary industry in India. It could be argued that the documentary, which has for several decades been neglected by the market, is now being pushed into several newer sites of public exhibition owing to rapid technological advancements. The community has witnessed several new funding opportunities for filmmakers. Organisations like India Foundation for the Arts and the Public Service Broadcasting Trust support the production of independent films by routing resources from funders like the Ford Foundation, the Ministry of External Affairs and Doordarshan among others. Additionally several new media labs, documentary resource initiatives and mentorship programs like the Film Bazaar at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI), the Indian Documentary Foundation (IDF), Docedge Kolkata and DocWok Delhi have taken up the task of connecting potential producers, foreign funders and collaborators with documentary filmmakers. The emergence of newer possibilities of funding, especially crowd-funding, growing avenues of global funding and distribution, and the possibility of reviving aesthetics has not only altered the documentary form but also the viewing experience. The last decade has also witnessed new opportunities for dissemination beyond the traditional film festival. In some rare cases, documentaries have managed to get theatrical releases and ticketed shows.

Traditional filmmakers have moved into the world of video installation art; private and state-owned television channels have started special documentary slots; and multiple virtual platforms have opened up the possibility of reaching out to newer audiences. There has also been a simultaneous development of an organic network at the grassroots where documentaries are being used for pedagogy as well as disseminated through local community screening spaces through community video and participatory video programmes under different development initiatives in the country.

An emphasis on documentary practice in mainstream media and film schools has also been an encouraging development. A pioneer in this kind of film training was Anwar Jamal Kidwai, former secretary of the Indian Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, who founded the Mass Communication Research Center (MCRC) in 1983. MCRC was set up with funding from the University Grants Commission and the Canadian International Development Agency (Lall 2004). The School of Media and Cultural Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences too has drawn funding from the Jamsetji Tata Trust to support the movement, and programmes like that at the Sri Aurobindo Centre for Arts and Communication, New Delhi, have designed dedicated courses for documentary filmmaking. There is also an increase in the production of documentaries at almost all film, design, art and media schools across the country.

The last three decades have been instrumental in re-defining a certain public image for the documentary form, conceived in terms of its materiality and aesthetic choices. Both the poor quality of the film stock as well as the rugged, grainy appearance of the analogue video lent a certain character to the documentary and to its relationship with the objective representation of reality. The lack of emphasis on the craft of filmmaking or the aesthetics of the image, and an overemphasis on the radical social impulse led to the documentary being seen as an inferior and less entertaining medium, especially when juxtaposed with its commercial and aesthetically pleasing fiction counterpart.

With the coming of financially affordable and technologically superior filmic apparatus, the old and outdated ‘look’ of the documentary started to get redefined in the 2000s. High definition video (HD) and affordable digital single-lens reflex cameras (DSLRs) have not only made filmmaking easier and accessible but has also radically changed the materiality of the documentary form. Moving away from the affinity with ‘imperfect cinema’[1], the documentary in contemporary times is undergoing a major change in terms of its aesthetic appeal and content. A form which was once likened to poor man’s cinema has now slowly transformed into the seamless edits of glossy high definition video images with tracking and dolly shots, semi-fictionalized formats and perfectly crafted and coloured frames which seem to suggest that the documentary is trying to catch the audience’s attention by coming aesthetically closer to its fiction counterpart.

Looking at the growth of independent documentary practice in India, it is easy to understand that films with radical potential of social transformation operate within the infrapolitics of funding, distribution, dissemination, censorship and access. Technology too has played an important role in shaping this form of activism. Another significant aspect of documentary activism, often marginalized in documentary scholarship, is the space of the post-screening discussion. An integral part of documentary culture in India, this space is significant for the very reason it exists. It is a space that enables direct conversation between the films, the makers and the audience. Issues raised in the film are discussed enthusiastically, creating a healthy democratic environment for the contestation of ideas.

Documentary film screenings are mostly free of cost and open to the general public. In the book, Screening Truth to Power: A Reader on Documentary Activism, authors Svetla Turnin and Ezra Winton, emphasize the importance of conducting screenings and holding discussions as an integral part of documentary activism. They argue that this activism ‘is an impulse that combines the affective and effective powers of documentary cinema, along with cultural political and social transformative community spaces that grow out of and inform documentary while activating new forms, pathways and modalities for social change’ (Turnin & Winton 2014).

When one talks about the documentary's transformational potential in order to advance progressive socio-political change, it is not merely the film text that one is referring to but also the space it enables for contestation of ideas, disagreements and dissent; of watching, listening and talking and thinking about the complex representation of ideas about society at large. In academic terms, the purpose of this space has been theorized as the ‘rhetoric of documentary’. Early theorization of the term understood it to be the argumentative quality of the documentary text, the means by which ‘effects are achieved’ and the ‘means by which the author attempts to convey his or her outlook persuasively to the viewer’ (Nichols 1991).

A more nuanced understanding of this rhetoric in the academia has proposed to include the performative relationship between the film and its audience, in other words, the interaction in the post-screening discussion space. It understands the performative in the interaction between the filmmaker and the audience as the ‘locus of civic education’ where the documentary has the potential to make the audience do something (Rabinowitz 1999). The interaction between the film and the audience as a dynamic space where ‘what is being produced is less a psychoanalytical and more an ethnographic scene; an encounter in which observation slides into participation which somehow exceeds transference and identification’ (Rabinowitz 1999).

Focus on the idea of an active audience falls in line with what Jane Gaines understands as political mimesis. To articulate her point, she quotes the example of an incident that took place at a screening of radical newsreel films during the anti-Vietnam War period at the State University of New York, Buffalo in 1969. ‘At the end of the second film, with no discussion, five hundred members of the audience arose and made their way to the University ROTC building. They proceeded to smash windows, tear up furniture and destroy machines until the office was a total wreck; and then they burned the remaining paper and the flammable part of the structure with charcoal’ (Gaines 1999).

Gaines’ conception of ‘political mimesis’ takes into account the acting bodies of the audience and interestingly comes close to Augusto Boal’s idea of the spect-actor that he formulates in the Theatre of the Oppressed, which includes participatory models like the Forum, Image Theatre, and Invisible Theatre. Bridging the gap between the actor and the spectator, between the one who acts and the one who observes, the space of ‘forum theatre’ invites spectators to participate with the actors on stage. The spectators could stop a performance and suggest an alternate dialogue or action and proactively decide how to take the performance forward. At times, the spectators could even replace the actor and perform on stage—what Boal understood to be a ‘spect-actor’—the one who is free to think and act, and the one who engages in self-empowering processes that can help foster critical thinking in an interactive space. This practice of theatre is what Boal considered to be a ‘rehearsal for revolution’.

***

‘If we think a picture is worth a thousand words, a moving picture is worth that many more. Documentary films are able to capture the reality of politics and strife in ways that are hard to erase’. (EPW 2015)

The documentary enables the audience to think critically and therefore poses a challenge to the mainstream media and its simplified political rhetoric. The documentary is not made in isolation; it comes out of a trustful relationship between filmmakers and the people they film. Nor is it screened in isolation, for there always exists a certain solidarity between the filmmaker, the organizing body as well as with the audience. Its long history of association with people’s struggles, and the culture of documentary activism that exists today give it the capacity to destabilize oppressive structures of power in society. It is because of this very strength that both official and unofficial censors have come down heavily on documentary filmmakers in the last decade. They fear the documentary today and it is in this fear that lies its true strength.

References

Economic and Political Weekly. 2015. ‘Unofficial Censors’, editorial, Economic and Political Weekly 50.35, August 29.

Gaines, J. 1999. Political Mimesis in Collecting Visible Evidence. University of Minnesota 6, pp. 84–102.

Garga, B.D. 2007. From Raj to Swaraj: The Non-fiction Film in India. New Delhi: Penguin Books.

Jain, A. 2013. ‘The curious case of the Films Division: Some annotations on the beginnings of Indian documentary cinema in Post-Independence India, 1940s–1960s’, in The Velvet Light Trap. The University of Texas Press, pp.15–26.

Jayasankar, K.P., and A. Monteiro. 2015. A Fly in the Curry: Independent Documentary Film in India. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India.

Lall, B. (n.d.) Before Bollywood! The Long, Rich History of Documentary in India. Online at http://www.documentary.org/magazine/bollywood-long-rich-history-documentary-india.

Nichols, B. 1991. Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary. Indiana University Press.

Rabinowitz, P. 1999. They Must Be Represented: The Politics of Documentary. New York: Verso.

Roy, S. 2007. Beyond Belief: India and the Politics of Postcolonial Nationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Turnin, Winton. 2014. Screening Truth to Power: A Reader on Documentary Activism. Concordia: Cinema Politica.

[1] The term ‘imperfect cinema’ comes from Julio García Espinosa’s critical essay For an Imperfect Cinema, an important piece of writing about Latin American Cinema. He defines imperfect cinema as one that avoids technical and artistic perfection and focuses on presenting social realities and concerns realistically in front of the audience without giving much emphasis to the aesthetics of the image.