Related issues are addressed in articles by C.M. Naim, 'The Other Attack on Taslima Nasrin at Hyderabad' (Outlookindia.com, August 11, 2007) and Ritu Menon, 'Is this a Mobocracy?' (Indian Express, November 27, 2007).

Sahapedia: Censorship is not new to India, or for that matter the world at large. Institutions the world over fear ideas and their free and fair dissemination. What do you feel distinguishes the current climate of censorship?

Nakul Singh Sawhney: When Martha Graham, legendary American dancer and choreographer, said, 'Censorship is the height of vanity,' it could have easily been written off as a bit of an oversimplified assertion if it didn't ring so true in contemporary India. Maybe 'vanity' could be substituted with 'megalomania' or even 'self-obsession' but the searing intolerance, reflected in the growing censorship in India in its many forms, is perhaps couched in a deeply sinister inability of the State to listen to, watch, read or even fathom an opinion different from that of the 'dear leader' or the saffron flag wielders who back him. In fact, the self-obsessive trumpets are blown so loud and at such high pitch today by the State (and the unofficial State players in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), with the mainstream media playing the amplifiers of this off-beat orchestra, that voices of dissent can easily go unheard even if they somehow manage not to be crushed and stamped out.

However, the bigger question being, can the State really impose 'censorship' today? With most forms of internet censorship easily bypassed, what is the efficacy of censorship? When films, books and the like are virtually impossible to remove from torrent sites, how real are the bans? The truth being, that perhaps the only ban that can and is being enforced is that on cow slaughter. And only one thing can ensure that ban: fear. An overwhelming fear that is driven into the hearts and minds of beef-eating communities by lynching Muslims who are associated with cattle or meat trade (though in the case of Akhlaq in Dadri, he wasn’t involved with either, and just a mere allegation of him consuming beef was reason enough to kill him) or Dalits (like in Jhajjhar and Una) is what constitutes the 'success' of the ban. That's where the storm troopers backing the current State play their part. Storm troopers who disrupt film screenings, book releases, seminars, etc.

The State is playing its 'official' role by banning films through the Censor Board and 'officially' ensuring its members find their way into film festival committees who in turn ensure that films critical of the current government don't find their way into such film festivals. One such example, from a previous edition of the current regime, was Rakesh Sharma's internationally acclaimed documentary film on the 2002 Gujarat pogrom Final Solution (2004) that was rejected by the Mumbai International Film Festival (MIFF) in 2004. It is this that sparked off the anti-censorship film movement called 'Vikalp'. More recently, Kamal Swaroop's film Dance of Democracy/Battle for Benaras (2014), which was banned by the Censor Board, was also rejected by the Reliance sponsored MAMI film festival.

However, the directors of these independent films are able to successfully organise private screenings in a manner which bypasses the Cinematograph Act (1952). Technical details in the Cinematograph Act allow for such private screenings. The only remaining option for the State then, to crackdown on such screenings, is to use their storm troopers. With the patronage of the State these storm troopers (a more apt description would be local goons) are ensured legal impunity or very minimal legal action.

S: You have personally been at the receiving end of this form of ‘censorship by vandalism’. Could you share some details about what happened?

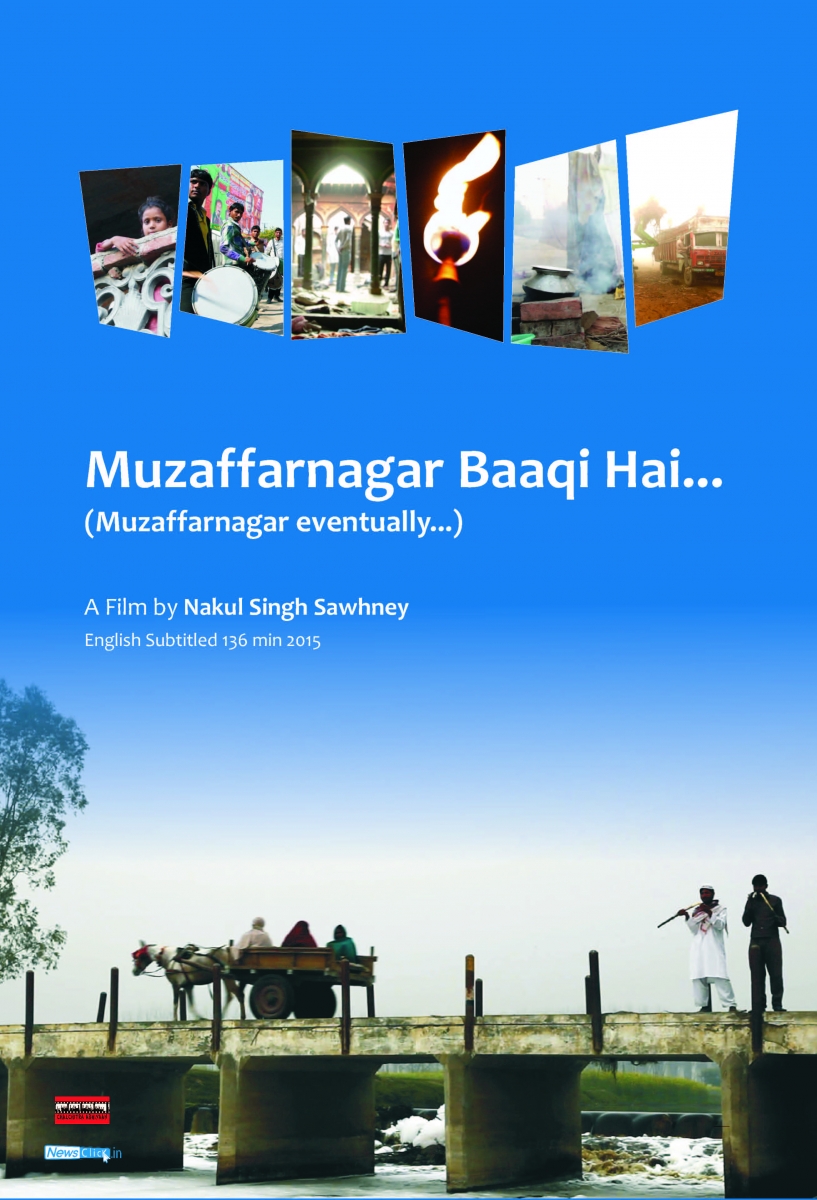

N.S.S.: On August 1, 2015, my film on the 2013 Muzaffarnagar and Shamli massacre, Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai... ('Muzaffarnagar Eventually...') was being screened at a college in Delhi University. The film lays bare the various social, political and economic aspects around the massacre. While speaking to a cross-section of people, the film tries to place the menace of religious bigotry and Hindu extremism within the context of caste and patriarchy.

While trying to deconstruct what is euphemistically referred to as the ‘Hindutva’ ideology, the film looks at how curbing women's rights and upholding the caste order are an intrinsic part of its worldview. It also looks at how the venomous ideology sprouted by the ruling dispensation split the once militant peasant union vertically along religious lines. Most importantly, the film looks at how various political parties, particularly the ruling BJP, tried to foster and then consolidate this religious strife for their electoral victory.

It wasn't very surprising then that the Sangh Parivar was opposed to the film. Roughly one hour into the film 30-40 workers of the ABVP (Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the students' wing of the RSS) stormed into the screening venue and demanded the film be stopped. Puzzled by the hooliganism, teachers and students tried to reason with them. But the modus operandi of the right-wing activists was clear. The idea was not just to express their opposition to the film but to threaten and intimidate the students and teachers present at the screening, to threaten the audience more than the filmmaker. Intimidation and fear in the minds of the public is the key to ensuring the cultural homogeneity that despotic rulers need for their survival.

S: What do you think it is about these documentary films that threatens the right wing and leads to the actions you described?

N.S.S.: Bans and censorship restrictions on films (in the form of scenes being cut to allow for the release of films) are not new and similar 'official' intolerance has been seen during past regimes as well. Legendary filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak's documentary film Amar Lenin (1970) which was banned during Indira Gandhi's regime is one such example. What is new, though, are the frequent visits of the storm troopers during film screenings.

Right-wing goons have cracked down on film screenings in the past as well. Among the many examples are the numerous attempted disruptions of screenings of Final Solution, the late Shubradeep Chakraborty's Encountered on Saffron Agenda? (2009), Sanjay Kak's Jashn-e-Azaadi (2007) and all of Anand Patwardhan's films over the years. A more recent example (and among the most shocking ones) was when ABVP goons in Pune physically attacked and injured some students of the prestigious Film and Television Institute of India in 2013 for organising the screening of Anand Patwardhan's film Jai Bhim Comrade.

So what is it about these films that scares the right-wing? Most of these films are very different and often even vary in their content and politics. What is common though, in the way they threaten the Hindutva ideology, is simply that they challenge the many notions of the nation-state thrown up by the saffron brigade. From their macho fantasies of a Hindu Rashtra, to the upholding of a Brahminical caste order, to the chest-thumping jingoistic celebration of the institutions of the police and army (specially in Kashmir and the Northeastern states, or the many contentious 'encounter killings', particularly of Muslims) and finally to the roles that women are expected to perform and conform to in their idealized monolithic Hindu nation. These are some of the many questions these films take on. The films try and delve into these questions with a degree of depth and complexity which irks the Sangh Parivar.

S: Is this indirect form of censorship mostly restricted to cinema?

N.S.S.: No, it's not just filmmakers who face the wrath of the official or unofficial censorship. Tamil writer, Perumal Murugan, decided to stop writing after receiving several threats from right-wing goons over his novel Madhorubagan ('One Part Woman'). In the past, one of India's most famous painters M.F. Hussain was also not spared their wrath. Some of his paintings had been vandalised and innumerable cases were filed against him, which forced him to live his last years in exile.

The impunity enjoyed by these self-appointed censors, has led to increasingly pernicious forms of censorship. In 2015, M.M. Kalburgi, an academic and former Vice Chancellor of the Kannada University in Hampi, was shot dead at his residence by unidentified men. The Hindutva right-wing had often raised objections to Kalburgi's studies on the Lingayat community. Shockingly, this wasn’t the first time an activist had been shot in cold blood. His murder was preceded by the assassinations of rationalist-activists Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare.

Not surprisingly, this censorship is mostly 'one way'. Bigoted videos and audio clips spreading venom against religious minorities in India are being circulated extensively on social media, particularly the mobile application, 'Whatsapp'. The content of the clips ranges from how young Muslim men are deceivingly wooing Hindu girls under false names (this phenomena is called 'love jihad' by the Sangh Parivar), how cows are being mercilessly slaughtered by Muslims, conversions of Hindus by Christian missionaries or just random videos and pictures of violence and gore, claimed to be of Hindus attacked by Muslims. Incidentally, one such fake video spreading false information was largely responsible for vitiating the atmosphere in Muzaffarnagar and Shamli districts just before the massacre. Ironically, the State has rarely felt the need to control or 'censor' the circulation of these videos. And this makes the bias of the State amply clear.

S: But can’t the State counter narratives that don’t suit it with its own propaganda machinery, which one assumes has a far wider reach than a documentary filmmaker would?

N.S.S.: Yes, and so the question that arises then is why should the State feel threatened? With a massive, well-funded propaganda machinery and a mainstream media controlled by big corporate houses which support the current ruling dispensation, even mainstream films (which are largely funded by corporate money as well) rarely challenge the dominant cultural, political, economic or social norms. One can't then, but help wonder whether independent documentary films which provide an alternate narrative really pose a threat? Well, even a couple of decades back the answer would have been a resounding 'No'. That has changed. With the evolution of digital technology, the production and dissemination of independent films has become cheaper, less cumbersome and hence, more democratic.

There are today many more independent filmmakers and more independent screening venues. This has facilitated the growth of independent, non-corporate and non-State funded cinema movements, An exemplary example of this is Cinema of Resistance, a film movement which has grown across several small towns of north India, where independent documentary films are screened and discussed. A movement which as the name suggests is not just an amalgamation of film festivals, but also a form of cultural resistance.

Several such smaller initiatives are mushrooming across other parts of the country. Activists on the ground are also gradually beginning to use these films as a means to start an engagement on issues they may be working on. Similar screenings are being organised more frequently by academics and educationists in university and college spaces. Many small film clubs have sprung up organising weekly or monthly screenings of such independent films at unconventional venues.

While such initiatives would still amount to just a fraction when compared to the penetration by the mainstream media and State propaganda (including the unofficial State in the form of the Sangh Parivar), nonetheless, the counter-narrative is slowly but steadily growing as well. Films are finding newer audiences, audiences are finding newer films. And finally, the internet too, is a newer form of dissemination, though in India its penetration is still limited. But all this makes the storm troopers all the more busy.

S: What do you feel is the way forward for this movement?

N.S.S.: So, the bigger question that the situation begs is, are we going to continue looking at censorship just as a behemoth that filmmakers, writers, artists, academicians etc. must fight? After all, it's them and their work which is at the receiving end of censorship. But if the struggle would solely rest on their shoulders, it is already a lost cause. Censorship is as much a violation of the audience's rights as it is of the filmmaker, perhaps more so. Therefore, the struggle against censorship has to be taken on by the audiences and filmmakers together. After all, in an era of bans and censorship, it is for the people to demand their right to be able to decide what to watch, what to wear, what to read, what to eat, what to listen to, etc.

Instances of this have already been seen. After ABVP disrupted the screening of Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai..., Cinema of Resistance raised a call to organise protest screenings against the disruption on August 25, 2015. The response was much bigger than anticipated. Over 70 screenings of the film, in 22 states and in over 50 towns and cities of India, were organised on that day. From universities to open mohallas. From middle class neighbourhoods to lower income group colonies. From open-air screenings to hired auditoriums. From people's houses to innovative makeshift screening venues. Audiences ranging from 15 people to 500. The message was clear. People asserted their right to watch the film they wanted to, and not what the State or their storm troopers would decide they watch.

Similar public assertions have been seen in the past. In 2007, an attempt to stop the circulation of Sanjay Kak's film Jashn-e-Azadi led to a spontaneous 'dispersed festival' of 100 screenings in 30 days. Even earlier in 2003 an attempt to stop Rakesh Sharma's Final Solution was met with a similar rush of spontaneous screenings.

What these responses to censorship also prove is that the State and their storm troopers don't necessarily reflect the public sentiment on censorship. In fact, quite to the contrary, it is a desperate attempt to clamp down on an audio-visual articulation of the pockets of resistance against a despotic state. Ultimately, the struggle against censorship is perhaps the struggle to uphold one of the core values of democracy: the right to dissent.